As a rainbow of social movements in Peru prepare for a general strike starting on 4 January the country is polarised between party politicians’ intrigues and action of the masses on the streets. Whether or not the strike will succeed in reinstating Pedro Castillo as the elected President, or push on to a popular constituent assembly remains to be seen. With 30 protesters killed by state forces in the two weeks up to Christmas, further repression under usurper Dina Boluarte can be expected. Whether repression will succeed in stemming the torment is another matter. One of the movement’s most popular slogans “Que se vayan todos! / They all must go!” indicates the popular hatred of the coup and counter-coup machinations of the political establishment.

What is clear is that the structural challenges that beset Castillo’s 18 month-long government have not gone away, and remain to be overcome for any real advances to be made. Peru’s political economy is still dominated by extractive capitalism that continues centuries of imperialist underdevelopment.

The ruling class promotes Peru as a ‘mining country’, a positioning that was especially emphasised under the Fujimori neoliberal opening of the 1990s that made the country attractive to foreign investment.1

Attractive means that foreign investors will make huge returns, but it requires the interests of most the population and the environment are entirely subordinated to the corrupt alliance of multinational capital with dictatorship inclined domestic bourgeoisie that lines its own pockets whilst overseeing the vast transfer of profits out of Peru.

Source: https://www.latindadd.org/2022/05/10/mineria-en-peru-ganancia-extraordinaria-2021-libre-de-impuesto/

But first a brief look at the global context in the mining industry, the world market in mineral commodities on which Peru’s economy is so dependent.

International mining corporations’ profits boom

The fortunes of international mining corporations accentuate the trajectory of the commodities super-cycle that extended for nearly two decades, reaching its peak from 2011 to 2014 until the dip in 2015, before a slow recovery again from 2017 onwards. In the years of incremental recovery, the top 40 global mining companies made around U.S. $65bn each year in net profits, rising to $70bn in 2020.2

The mining industry’s upswing was then put on hold by Covid, but is once again on the rise. The return of high commodity prices in 2021 saw the annual net profits for this elite group of mining monopolies shoot up, more than doubling to $159bn.3

The mining boom is back. By 2021 and 2022 two factors conjoined to hugely boost mining revenues: volumes increased due to industrial demand on the uptick; and prices increased as a result of the strengthening of the U.S. dollar against the national currencies of most producer countries. When sales prices are designated in dollars, and much of the production costs are in local currency, a depreciation of the local currency vis a vis the dollar gives rise to widening the margin between revenue and costs. The mining corporations are again enjoying huge surplus-profits, over and above the average rate of profit. The main indicator of corporate profitability, the annual return on capital employed, from 11% in 2020 to 21% in 2021, and is expected be at a similar level for 2022.4

Where does all this money come from, if not at the expense in the producer countries of exploitation, expropriation and evasion of the full real cost of industrial scale mining?

Source: https://www.mining.com/peru-sees-60-increase-in-mining-tax-revenues/

Trade positive yet balance of payments negative: the profits outflow.

Minerals constitute an average of 58% of all Peru’s exports, even higher in 2021, followed by foodstuffs and related raw materials. The country is set up to serve capitalist extraction of its natural diversity and wealth, it has an “export-oriented economy”. Copper is the most significant commodity, comprising 33% of all exports in 2019, with gold at 16% (see Table 1). Raw materials and foodstuffs together comprise over 90% of all Peru’s exports.

Table 1: Principal Exports from Peru 2021

| Item description | Value FOB

(US $ bn) |

Proportion of total | Value FOB

(US $ bn) |

Proportion of total |

| Mining | 40,314 | 63.9% | ||

| Copper | 20,698 | 32.8% | ||

| Gold | 10,121 | 16.0% | ||

| Agriculture | 8,809 | 14.0% | ||

| Fisheries | 3,862 | 6.1% | ||

| Oil and natural gas | 3,711 | 5.9% | ||

| Other | 6,410 | 10.1% | ||

| Totals | 63,106 | 100.0% |

Source: Ministerio de Energia y Mineria (MEM) 5

Peru supplies 12% of global copper production, second only to Chile where 28% of the world’s copper supply is produced.6 Over two thirds (69.3%) of Peru’s copper exports went to China in 2021. India, Canada and Switzerland each took about a quarter of Peru’s gold exports.7

We need to follow the money and not just the material goods, to see where the profits from Peru’s extreme export orientation end up.

According to the national accounts Peru ran a significant surplus in trade (exports less imports) of U.S. $14.8 bn in 2021.8 The trade balance is reduced once a deficit in services (mostly payments for transport) of $7.3bn is taken into account, but even so the resulting balance of goods and services combined remains positive at $7.5bn. However, once all payments are included, Peru had a negative current account balance of $5.3bn. Despite generating a trade surplus from the ‘real economy’, the country’s international financial position ended up seriously worse at the end of the year.

How is the trick pulled? A closer look at the national accounts shows that the reason for Peru’s negative current account was a deficit on ‘balance on income’ payments of $18.1 bn in 2021.9 What are called ‘income payments’ in the IMF standard categories are in fact capitalist property income payments such as profit transfers and interest payments on loans, in other words forms of profit.

The breakdown of these money movements is most revealing. There were $1.3bn property income payments in and $19.4bn property income payments out, resulting in a net profits outflow from Peru of $18.1 bn in 2021. Of this, the main items of overseas profit transfers were $15.7bn in company profits, $1.4bn in private sector interest payments and $2.4bn in public sector interest payments.10

The outflow of $15.7bn company profits in 2021 was a record, higher even than the profit outflows of $12 bn registered in 2011 and 2012 at the previous cycle peak.11

Let us emphasise what the dry figures are telling us: these vast money outflows indicate the value transfer that is the hallmark of underdevelopment. There is far more commodity value produced in the Peru than is consumed by its residents, which prima facie should lead within short measure to an expanding capitalist economy, yet it does not because there is a constant outflow of the major share of the profits, causing a balance of payments deficit. Then this financial deficit is made up by loans that in turn require interest payments, further deficits pushing the country ever deeper into the mire. The result is that the destruction stays at home whilst most the financial gains are realised in comfort overseas. These mechanisms of imperialist extractivism produce and reproduce underdevelopment.

A protest near the Antapaccay copper mine in 2021. Source: : Peruvian Government

Present and Future Mining Mega-projects in Peru

The biggest profits are those of the mining corporations that operate colossal open cast mines, mostly high up along the Andes mountains, with devastating immediate consequences for the surrounding environment and communities nearby.

The mining companies operating in Peru made U.S. $8.02 bn net profits out of $15.70 bn total profits in 2021, that is more than the rest of the entire economy put together.12

Seven company projects comprised 89% of Chile’s copper production in 2021 (see Table 2).

Table 2: Major Copper Projects in Production, Peru 2021

| Project | Region | Proportion of production | Owning company (s) | Origin of investment/ destination of profits |

| Antamina | Ayacucho | 19.8% | BHP | Australia/UK |

| Cerro Verde | Arequipa | 19.2% | Freeport 53.5%

Sumitomo 21% Various 25.5% |

US

Japan Peru |

| Southern Perú Copper | Moquegua | 15.9% | Minera México | Mexico |

| Las Bambas | Apurímac | 13.1% | Glencore Xstrata sold to MMG | Swiss/UK then China |

| Toromocho | Junín | 8.1% | Chinalco | China |

| Antapaccay | Cusco | 7.8% | Glencore | Swiss/UK |

| Marcobre | Ica | 5.3% | Minsur 60%

Alxar Internacional 40% |

Peru

Chile |

| Others | 10.8% |

Source: Ministerio de Energía y Minas (Minem), p4 13 and company reports.

The sector has 234 thousand direct workers, of whom 72% are sub-contracted and not company employees.14

The mining projects have been resisted by communities many times. In 2015 Southern Peru’s planned expansion into the Tia Maria project was met by massive strikes and road blocks, with state forces injuring dozens and killing two local farmers concerned about the loss of their water supplies. That same year communities around Las Bambas set up road blockades, and thousands surrounded an IMF summit promoting corporate mining.15 By 2021 social movement protests had forced the suspension of 10 mining projects, including Las Bambas. The communities’ point out “the pollution from mines affecting their drinking water, a lack of infrastructure investment or job creation and that the dust from heavy trucks is killing their crops and livestock”.16

A protest near the Antapaccay copper mine in 2021. Source: : Peruvian Government Corporate investors initiated claims against the Peruvian state with the undemocratic international investor—State dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms on five occasions during 2021, the highest in the world that year.17 Their purpose to demand compensation for profits, supposedly lost due to social disputes.

There are two completely different narratives at loggerheads on large scale mining. The mainstream media propagandises in favour of the corpora, with politicians and tame professors preaching the positive benefits; this runs completely counter to the lived experiences of the working people in rural communities, both campesino and indigenous. The conflicts are no more or less than the fight for life.

With more strikes and protests in 2022, Pedro Castillo’s government sought to mediate these multiplying social-environmental conflicts, to find negotiated solutions between the main parties. But mediation cannot resolve the structural roots of the problem, that requires a complete rejection of the entire capitalist extractivist model. If anything, the overall antagonism is set to intensify rather than abate.

Expected movements in the world market come heavily into play in terms of corporations’ principal investment decision to go beyond the exploration and feasibility stages, and to develop any given mining project into production. Copper is used for electricity transmission and one of those strategic minerals whose demand is expected to increase in the coming decades of energy transition. The current international price of copper is $4.43/lb, already an increase of 23% over 2021 levels.18 Copper prices are expected to increase further; around 25% by 2030 and, with less predictability, possibly even doubling by 2040.

At these forecast prices, international corporations are eager to open up new investments, to extract more and more copper (see Table 3), in order to produce more and more profit.

Table 3: Peru Mining Forecast Investments by Country of Origin

| Country of origin | Number of projects | Forecast Investment (US $bn) | Proportion of Total |

| UK | 6 | 12,066 | 20.9% |

| China | 5 | 10,155 | 17.6% |

| Canada | 11 | 8,489 | 14.7% |

| Mexico | 4 | 7,684 | 13.3% |

| US | ** | 7,500 | 13.0% |

| Peru | 7 | 4,581 | 7.9% |

| Others | ** | 7,307 | 12.6% |

| Totals | 48 | 57,772 | 100.0% |

Source: Minem.19 (** Unspecified, 15 projects between the U.S. and others)

The forecasts, based on company supplied information and reported by the Peruvian mining ministry, show that corporations from five countries are set to dominate foreign investment in mining in Peru, they are the UK, China, Canada, Mexico and the U.S. that between them will source 87% of all investment.20

To get to the specific corporations we break down the country figure in the case of the UK (see Table 4).

Table 4: Forecast Mining Investments in Peru from the UK

| Project | Location | Company | Forecast investment (US $bn) |

| Quellaveco | Moquegua | Anglo American | 5.300 |

| La Granja | Cajamarca | Rio Tinto | 5.000 |

| Fosfatos Mantaro | Junín | ITAFOS | 0.850 |

| Los Calatos | Moquegua | Minera Hampton | 0.655 |

| Optimización Inmaculada | Ayacucho | Hochschild | 0.136 |

| Ariana | Junín | Southern Peaks Mining | 0.125 |

| Total UK companies | 12.066 |

Source: Minem.21

It is clear from the above that Anglo American’s Quellaveco and Rio Tinto’s La Granja projects dominate and their production volumes will be huge, as are their profit expectations.

Note that official presentations always present the incoming foreign investment, but rarely do they report the underlying purpose which is to take more money out as profit as a return on the investment, over and above the initial capital advanced. These forecasts are what drives the entire enterprise, and do get reported to investors rather than the general public.

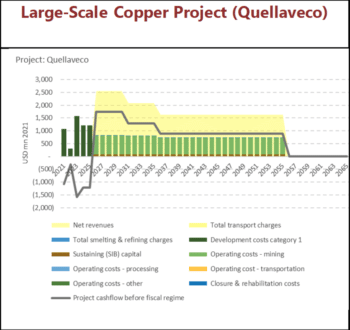

Anglo American’s Quellaveco project serves as the data for the IMF model of a large-scale copper project, giving it a higher profile than usual and allowing a summary view of the profit projections. The project is due to enter production in 2026. It has up front five-year development costs estimated at $5.3bn. The projected lifespan of production runs for 30 years until 2055. During this time the project as outlined will generate operating profits (revenue, less operating costs) of around $32bn, six times more than the initial investment.22

If the state’s tax regime stays more or less as it is currently (see next section), Anglo American can deduct highly depreciated capital expenditure from its taxable profits, and on this estimate will end up with around $21 bn net profit, that is four times more than its initial investment.

Corporations like Anglo American insist on gaining state assurances of an operating environment that both controls social opposition and offers a stable tax regime, both with the underlying motive of guaranteed future profits. This continued capitalist extraction requires a compliant state in the dual role as corporate facilitator and enforcer. And so, to the politics.

Source: IMF Technical Report (2021), p78.

The battle over taxing corporate mining profits

Fujimori in the 1990s paved the way for the Peruvian state to be highly compliant with large scale destructive mining in the 2000s. This was on two fronts: a light touch regulatory regime, and a heavy hand that was quick to criminalise any social opposition. In this regard Peru’s ruling class has for three decades been running a similar ship to its neoliberal neighbours Colombia and Chile.23

Peruvian society still suffers from the entrenched neoliberalism. The state’s total tax revenue is just 14.6% of GDP, that is a step lower than Chile (19.2%) and Colombia (17.8%).24 Consequently, state expenditure per head is especially low in Peru. This is the lasting effect of Fujimori’s reign, perhaps as deeply damaging economically as the Pinochet dictatorship’s extreme right-wing legacy.

From Fujimori on government policies have been friendly towards large scale mining, in particular what is known as the mining fiscal regime, i.e., how mining corporations are taxed. There are two broad strands: a) the standard corporation tax generally applicable to all corporations, known as ‘income tax’; and b) mining specific tax regime that has two elements i) concessions for mining corporations that allow them to reduce the income tax they pay, and ii) mining royalties.

For our analysis it is important to keep three framing points in mind:

- First royalties are due to the state in its capacity as sovereign owner of non-renewable natural resources that are being extracted, the state as the ‘landowner’, and are considered as a type of rent. Internationally, royalty rates in mining are much lower than they are for oil and gas, usually just in single percentage figures, i.e. less than one tenth, of sales revenue.

- Secondly, the commodities super-cycle saw mining sales revenues increase dramatically and, since their cost base remained fairly stable, the spectacular multiplying of corporate profits. These were truly surplus-profits or super-profits.25

- Thirdly, in Peru as elsewhere about three quarters and more of state tax revenue from the mining corporations comes as corporate income (i.e., profit) tax rather than mining specific royalties.

This was the situation when the previous government of populist Humala switched the basis of mining royalties from a percentage of revenues to a percentage of profits in 2011. The immediate effect was a near tripling of the state’s royalty revenue in 2012. But, from a very low starting point.26 In reality Humala’s bark was sharper than his bite, as one pro-business market analyst commented “revised policy in Peru was well received within the industry”.27

Even in the new system, royalties were still no more than a fraction of profits, that the mining corporations could easily afford. Official institutions, the state bank and government, present royalties and related mining taxes in Peruvian currency, the sol; and report these separately rather than as elements of the mining industry’s overall profit stream. Deliberately or not, this method disguises just how small a percentage the royalties still are, even after the 2011 reform. Detailed analysis calculates the 2011 royalty package at just 7% to 12% of corporate profits, depending on particulars. Thus, with corporation tax at 29.5%, the combined taxes were 37% to 42% of company profits.28

The next big move came in the run off second round of the 2021 presidential election campaign when Pedro Castillo advocated further reforms including “renegotiation of mining contracts, an increase in company taxes, and potential nationalization of mines”. His opponent, Keiko Fujimori advocated a new mechanism that would share out of 40% mining royalties to individual households, seeking to neatly identify individual welfare with corporate profits. A clever trick seeking to milk “widespread lack of trust in the political establishment and government institutions” that her own father had done so much to corrupt from within. In the event Castillo got many more votes from people in the parts of the country suffering the immediate effects of mining, bringing him into the Presidency in June 2021.29

Just one month later, in July 2021 Castillo’s newly ensconced administration underwent a classic ‘moderate shift’ away from his radical election campaign, to courting the mining industry, proposing no more than incremental increases in tax rates. His orthodox finance minister set out different options to raise the Peru’s overall ‘state take’ of mining profits from around 41% to around 44%. However, this was met with furious opposition by the Chamber of Mines, representing the mining corporations. The Chamber made hyperbolic claims that Peru’s tax rate was already close to 50% and any further increase risked it losing over $50 bn future foreign investment. Finance Minister Pedro Francke pointed out the falsity of these claims, that his proposed increase would still leave the rate lower than in the neoliberal model regime Chile (47.1%).30

Castillo’s government then ‘invited in’ the IMF to look at the tax options. The IMF’s technical report came out in December 2021. It recognises that because of the dramatic increases in their gross profits the mining corporations could pay the proposed tax increase, and still come out ahead on net profit. Their detailed estimates reveal that currently the mining corporations’ internal rate of return (a close proxy to the net rate of profit) is 25%.31 At this high rate the capital invested doubles in just over three years.

Moreover, the IMF estimates that Peru’s Average Effective Tax Rate (AETR), is at the lower end of the international range, that varies widely from 30% to 75%. The IMF acknowledges that “the current fiscal regime for mining in Peru is competitive.”32 Crucially, having examined the options in detail, the IMF concludes that Castillo’s proposals were in fact fairly cautious. It states “this increase in the tax burden would keep Peru in the mid-range of other mining countries, since its relative position would not be modified.”33

The IMF is of course the bastion of financial orthodoxy. A more critical analysis of official figures by Juan Torres Polo demonstrates that, in 2021 the corporations avoided (or evaded) paying the full rate of corporation tax on their extraordinary profits, underpaying the nominal tax level to the tune of 11,907 million soles (US $3.1 bn at the exchange rate of 3.88 sol/dollar).34

But the dirty tricks campaign was already underway, the radical right frenzy had been unleashed.35 Another factor was in play, the class struggle. The Huancuire indigenous community had blocked production at Las Bambas copper mine, and production at Cuajone mine had been halted as well.36 Through the press, mining executives urged the government to “quell social uprisings”, or itself face the consequences.37 Castillo tried to navigate a path between these two fundamentally counterposed perspectives, and ultimately failed. His presidency lost its coherence and began to decompose. The mining ministry opposed the finance ministry, and the majority of Congress sided with them.38

Castillo had been tamed, but that was no longer enough. He in turn had to either break the resistance of social movements or be ousted. In the event Castillo’s removal was a confused combination of contending political interests, and he now sits in prison with at least 18 months ‘preventative detention’ before facing trial.39

Urgent need for anti-imperialist solidarity

Our analysis shows that there is roughly a 60:40 split in mining super-profits shared between the international mining corporations and the Peruvian state. In empirical terms this is the neo-colonial deal that is committed to by the political forces both sides, a deal that cements their vested class interests in keeping the extractive machine running whatever the consequential social and environmental damages.

We argue the need for anti-imperialist solidarity with the uprisen peoples of Peru that takes their fight into the citadels of capitalist power behind the throne. As with the heroic Mapuche political prisoners on hunger strike in Chile, urgent actions are called for.40

The protracted war against corporate mining goes much deeper than the latest skirmishes around tax rates. It is a liberation struggle that stretches over five centuries. The indigenous movements in particular are fundamentally against capitalist extractivism in all its forms. Aligned with this perspective, critical Latin American academics have adopted the term ‘sacrifice zones’ to capture the plight of communities and territories blighted by mega-projects. Zones where living beings do not count as any more than peripheral collateral damage sacrificed to profit making and capital accumulation.41 As the state and corporations cement their collusion it is not only communities but whole countries that are sacrificed in these neo-colonial arrangements. Peru is a sacrifice zone for imperial plunder.

Dina Boluarte’s usurper presidency knows only too well that a guarantee of continuing super-profits is the what must be delivered from her side of the deal; in exchange for diplomatic, and as necessary military, support from the imperialist states. If her regime fails to discipline the country into submission, then contingency plans for intervention will surely be put in motion.

Except the people are risen, they will have a say. We do not yet know the outcome of the general strike. The jury is out, it is they who are on the streets. And it is their agency that will determine whether the time for sacrifice has come to an end.

12th October Platform—The Resistance Continues.

Notes:

- ↩ Roberto Schatan, Eduardo Camero, Juan Carlos Guajardo, Victor Mylonas and Ricardo Villalobos Proposals for the 2022 Tax Reform: Mining Sector Fiscal Regime, Capital Gains, and IGV on Digital Services IMF Technical Report, December 2021, p15 at www.imf.org

- ↩ PwC Mine annual report, various years, at www.pwc.com

- ↩ PwC Mine 2022: A critical transition at www.pwc.com

- ↩ Ibid, p15.

- ↩ Detail for 2021 in Ministerio de Energía y Minas (Minem), Boletín Estadístico Minero Edición N° 01-2022, p9 at https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minem/informes-publicaciones/2793697-boletin-estadistico-minero-enero-2022. Summary at statistics.cepal.org See also IMF Technical Report, p15.

- ↩ PwC Mine 2020: Resilient and Resourceful, p5. See Chile’s Copper for the Chilean People at londonminingnetwork.org

- ↩ Minem, Boletín, p10

- ↩ statistics.cepal.org

- ↩ The full picture includes other transfers and movements.

- ↩ Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (BCRP) Data, Renta de Factores at estadisticas.bcrp.gob.pe

- ↩ BCRP Data, Egresos Privados—Utilidades at estadisticas.bcrp.gob.pe

- ↩Utilidades de empresas fueron menores en US$ 594 millones: tres sectores claves en rojo at gestion.pe

- ↩ Minem, Boletín, p4.

- ↩ Minem, Boletín, p14.

- ↩ www.resilience.org

- ↩ www.thedialogue.org

- ↩ UNCTAD World Investment Report 2022: International Tax Reforms And Sustainable Investment, p74 at unctad.org

- ↩ PwC Mine 2022, pp9-10

- ↩ Cited in Reino Unido supera a China en inversión minera en el Perú at andina.pe

- ↩ In recent years Canadian scholars have provided critical analysis of the imperialism of their ruling class that surpasses in its concreteness what has been achieved in the UK. See for example Todd Gordon and Jeffery R. Webber (2016) Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America, Chapter 6; Todd Gordon and Jeffery Webber (2018) ‘Canadian capital

and secondary imperialism in Latin America’, Canadian Foreign Policy Journal. - ↩ Cited in Reino Unido supera a China…

- ↩ IMF Technical Report, p78.

- ↩ For a comparative analysis of the economic policies of the neoliberal and social democratic state regimes in the Andean region during the previous round of the ‘pink tide’, see Andy Higginbottom (2013) ‘Foreign Investment in Latin America: Dependency Revisited’ in Latin American Perspectives, Vol 40 (3); 184-206.

- ↩ Figures are for 2019, from IMF Technical Report, p13.

- ↩ The fluid interchangeability between profit and rent arises from the fact that they are both external forms of the surplus-value that is extracted by the producing capitals from the exploitation of labour and the expropriation of natural wealth. Karl Marx explained how in capitalist agriculture landowner rent is a converted form of ‘surplus-profit’, that is over and above the general rate of profit, made possible by the productivity of agricultural labour. Capital, Volume 3, Part 6. Lenin designated the consistently higher profits of monopoly capitals as ‘super-profits’ in Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Samir Amin designated the term ‘imperialist rent’ to express the idea of international value transfers, see his The Law of Worldwide Value.

- ↩ See IMF Technical Report, p16.

- ↩ Francesca Rey The effect of changes in Peru’s mining tax at pages.marketintelligence.spglobal.com

- ↩ IMF Technical Report, p23.

- ↩ Chloe Schalit, Supriya Sadagopan and Mario Picon The management of mining revenue in Peru at r4d.org

- ↩ ‘Peru mining chamber says tax hike proposal risks $50 bln investment’ Reuters at www.reuters.com

- ↩ IMF Technical Report, p24.

- ↩ IMF Technical Report, pp26-27.

- ↩ IMF Technical Report, p38.

- ↩ Juan Torres Polo, ‘ Minería en Perú: Ganancia Extraordinaria 2021 libre de impuesto’ at www.latindadd.org

- ↩ José Carlos, Llerena Robles and Vijay Prashad ‘There’s a dirty tricks campaign underway in Peru to deny the Left’s presidential victory’ MR Online at mronline.org

- ↩ ‘Paralización de Las Bambas y Cuajone generó que el Estado deje de recibir US$ 7 millones diarios’ rpp.pe

- ↩ ‘Analysis: Peru’s mining execs ‘lose faith’ in gov’t despite moderate shift’ Reuters at www.reuters.com

- ↩ ‘Peru says IMF sees leeway to hike taxes on mining sector -finance ministry’ Reuters at www.reuters.com

- ↩ ‘A Massacre in Peru: Death Toll Tops 17 as Protests Mount After Ouster & Jailing of President Castillo’ Democracy Now’ at www.democracynow.org

- ↩ ‘Llamado urgente de solidaridad hacia el pueblo Mapuche y la CAM’ / Urgent call for solidarity with the Mapuche people and CAM at contrahegemoniaweb.com.ar

- ↩ For a good example see Valenzuela-Fuentes, K.; Alarcón-Barrueto, E.; Torres-Salinas, R. ‘From Resistance to Creation: Socio-Environmental Activism in Chile’s “Sacrifice Zones”’. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3481. doi.org