In the new era

Despite the punishments

We are grown

We are alert

We are more alive

To rescue each other

In the new era

Despite the dangers

Of brute force

Of the frightening night

We are in the struggle

To survive

So that our hope

Is more than revenge

Is always a path

That is left as an inheritance

—Lyrics from “Um Novo Tempo” (“A New Era”) by Ivan Lins

On April 14, 2023, Brazilian president Lula da Silva arrived at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to meet with President Xi Jinping on his official state visit, his first since being reelected into the presidency in January 2023. Welcoming him was a band playing a popular Brazilian song released in 1980, called “Um Novo Tempo” (“A New Era”) by Ivan Lins, a song marking the transition out of a twenty-year military dictatorship. “A New Era” also fittingly describes the new stage that Lula’s return signified for China-Brazil relations, which had been strained under former president Jair Bolsonaro.

In 1993, Brazil was the first country to establish a “strategic partnership” with China, a relationship that has deepened and broadened at an impressive rate since. In fact, according to the Brazilian government, since Lula’s first visit to China twenty years ago in 2004, trade between the two countries had increased twenty-one times, with Brazilian exports surpassing the $100 billion barrier for the first time this year. Lula’s visit resulted in fifteen agreements and $10 billion in investments from China, which included expanded collaboration in space, digital economy, the automotive industry, and renewable energy, among others sectors.

This year, Brazil and China celebrate fifty years of official diplomatic relations. In this historic year, there are a few highly anticipated events, including the June meeting of the Sino-Brazilian High-Level Partnership and Cooperation Commission, the main mechanism of bilateral dialogue created during Lula’s first term. The presidents are set to meet during Xi’s November state visit to Brazil, which is hosting the G20 Leaders’ Summit. The importance of the Sino-Brazilian relationship cannot be underestimated in the context of the rise of the Global South, the decline of U.S. hegemony, and the emergence of a New Cold War. With a look back into the history of bilateral relations, how can we understand the importance of these two countries in the current conjuncture in pushing forward changes unseen in a century?

In analyzing the China-Brazil relationship, much contemporary analysis looks at the period after the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1974. The period that followed was marked by several important events including in 1984, when then-president José Figueiredo, the last leader of the military regime, visited China. A year later, Premier Zhao Ziyang visited Brazil. In 1988, Brazilian president José Sarney visited China and met with Deng Xiaoping, and together, they predicted that the twenty-first century would be the “Pacific century and the Latin American Century.” Notably, there is relatively little contemporary scholarly research that focuses on the relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Brazil prior to this period, particularly the 1950s and ‘60s.

Similarly, much of recent scholarship has focused only on economic nature to the Sino-Brazilian relationship. The interest has grown with the rise of China globally in the past decades, and its increasing presence in Brazil and Latin American more broadly. The interest in bilateral relations is focused on Chinese foreign policy oriented towards investments in agriculture, mineral, and energy commodities in the region. This resulted in China becoming the main destination for Brazilian commodity exports by 2009, while China became a main exporter of manufactured goods to Brazil. Recent investments have seen a shift from commodities towards infrastructure (including 5G, electricity transmission, electric vehicles, and so on). Both trends have generated impressive results, but also a variety of contradictions and criticisms, from the mass deforestation of the Amazon Rainforest to produce soy earmarked for China to the State Grid Corporation of China acquiring a controlling share of Brazilian state-owned energy company, CPFL Energia, as part of the local government’s neoliberal policies of privatization.

Research on Sino-Brazilian cultural and people-to-people relations was largely done by Western scholars against the backdrop of the Cold War. This work tends to frame China’s efforts to build relationships with Brazilian and other Latin American intellectuals and leaders in the 1950s and’60s as “cultural diplomacy” (per Cecil Johnson and William E. Ratliff). In other words, the construction of cultural and economic ties prior to the establishment of diplomatic relations is seen as being part of China’s policy to win over Communists and non-Communists. In recent years, there have been some scholars (such as Rosario Hubert, Fernando Wei Ran, Wang Siwei, and Fan Xing) who are revisiting the cultural and intellectual exchanges between the two countries in this period.

While there is significant Brazilian scholarship analyzing the events surrounding the 1964 civil-military coup, there has been little attention paid to the relationships that leftist intellectuals and leaders had with China in the increasingly anti-Communist climate of the time. 1 On the sixtieth anniversary of this coup, which changed both the course of the country’s history and Sino-Brazilian relations, this article aims to recover some of the cultural, economic, and political ties between the two countries that long precede official diplomatic ties. In particular, this article focuses in on the struggles for agrarian reform and national sovereignty as common threads that connected the two countries. In Brazil, the struggle for land reform was led by the Peasant Leagues, and the struggle for an independent path to development was led by then-president João “Jango” Goulart. Both movements share an interconnected history with China and the Chinese Revolution in the lead-up to the 1964 coup. It was in the Cold War context and the U.S.-led global anti-Communist campaign where these two revolutionary tides met, from the countryside of the Brazilian northeast and the young capital, Brasilia, to Beijing.

This article is divided into four parts. The first focuses on the construction of an anti-Communist narrative by the United States and conservative sectors of Brazil in the lead up to the coup, linking the Brazilian struggle for land reform with the young PRC. The second looks at the tradition of “popular diplomacy” between the peoples and organizations of Brazil and China, in which land reform recurs as a connecting thread—an ongoing and unfinished struggle in Brazil. The third part explores the relationship between the Peasant Leagues of Brazil’s northeast and China and the means through which agrarian reform could be won. The fourth and final section looks at how the narratives constructed in this Cold War period linking Brazil’s struggle for agrarian reform with China continue to have relevance in today’s “New Cold War.”

Just as Lula declared last year on his visit to China, “No one will prohibit Brazil from improving its relationship with China.” This was said the day after he visited the research center of Huawei, which he called “a demonstration that we want to tell the world we don’t have prejudices in our relations with the Chinese.” The speech was followed by the announcement of a cooperation agreement between the two countries regarding semiconductors. This “new era” of relationship between China and Brazil is a bold statement in the face of economic, political, and mediatic aggressions waged by the United States, which has continued to increase its suppression of China’s advancement through the many means it has at its disposal. Recovering this history of the Sino-Brazilian and people-to-people relationships in the 1950s and ’60s gives us some insight into the present moment, as the two countries celebrate half a century of formal relations.

April 1, 1964: The “Communist Threat” from the Brazilian Northeast to China

The Threat of Agrarian Reform

“Today, the agrarian issue is, without a doubt, the factor behind all this unrest,” said then-Brazilian federal deputy Francisco Julião sixty years ago.2 Julião, who was a lawyer and a leader of the Peasant Leagues (as Ligas Camponesas) was making his last speech at the National Congress in the capital of Brasilia. The “unrest” that he was referring to was the military-led coup that was underway in his country on that very day, and this was his sign-off message: “At its core, what is being discussed in Brazil is the need to transition from a regime that was unaware of the existence of these 40 million slaves to a regime in which these 40 million servants participate in order to give their opinion to a minority group of ‘I don’t want this to happen,’ but it will happen,” Julião was referring to the forty million poor and dispossessed Brazilian peasants and agricultural workers who were at the center of the struggle for agrarian reform in the country. Shortly after this speech, Julião was stripped of his title and the Peasant Leagues were declared illegal; he went into hiding in rural areas of the state of Goiás. Thousands of peasants and other political militants were arrested, tortured, and murdered, as the country entered a very dark twenty-one-year period of its history under a military dictatorship.

In the hours before Julião made his final speech at the National Congress, General Olímpio Mourão Filho had already mobilized his troops in Minas Gerais state toward Rio de Janeiro to overthrow the leftist president Goulart. The discontent with Goulart among the conservative sectors and the military had been escalating for some time, culminating in the rally at Rio de Janeiro’s Central do Brasil train station, where Goulart announced the Decree of the Agrarian Reform Superintendency just two weeks earlier. This decree included the expropriation of underutilized national properties for agrarian reform, the nationalization of private oil refineries, and the granting of labor rights to rural workers that were equal to those of their urban counterparts.3 But this would prove too much for the ruling elites, and in the days that followed, all the signs were pointing towards a coup, from calls for impeachment to massive marches led by the conservative Catholic Church, and, finally, to the military mobilizations that took place from March 31 to April 1, 1964.

In Brazil, the line of succession applies when a president dies or resigns, or is incapacitated, impeached, or out of the country, but none of these applied to Goulart—this was a military coup d’état. In the early hours of April 2, 1964, the president of the Senate, Auro Moura Andrade, declared, without any constitutional backing, that Goulart was deposed of his position, and a new president, Ranieri Mazzilli, was swiftly sworn in. U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson was quick to send his “warmest wishes” just hours after Mazzilli was sworn in, before Goulart had even left the country—eventually living in exile in neighboring Uruguay. The New York Times carried this story on its front page on April 3. In the article, Latin American correspondent Tad Szulc referred to the events as “the removal of the immediate communist threat,” blaming the “Goulart regime” for the country’s debt and budget deficits, its rejection of the U.S. Alliance for Progress, and the suspension of U.S. aid to Brazil.4 The White House’s swift response, however, should come as no surprise, and much has been since revealed and written about ’U.S. involvement in the destabilization of Goulart’s government, leading to direct collaboration with the military in the coup.5

In the preceding years, the United States had been paying keen attention to the northeast of the country, where the Peasant Leagues had been mobilizing peasants in great numbers in the face of extreme inequality. According to Maria Rita Kehl, a Brazilian psychoanalyst, writer, and member of the National Truth Commission on the human rights violations of the military dictatorship, there was concerted effort by U.S. media to equate the “danger of agrarian reform” with the “communist threat,” with a strong focus on the Peasant Leagues and the northeast of Brazil.6 In his article “Northeast Brazil Poverty Breed Threat of Revolt,” Szulc, who had been reporting from the region for New York Times, wrote that in some northeastern areas, 75 percent of residents were illiterate and men and women lived for, on average, twenty-eight years and thirty-two years, respectively.7 In this context of desperation, Szulc claimed, “peasants are wooed” not only by the Peasant Leagues, but by local governments and politicians who were supported or influenced by communists. This is but one article among several published in the U.S. mainstream media prior to the coup, sounding alarm bells of the so-called communist threat in the northeast of Brazil—and they could not afford another Cuba in their self-proclaimed “backyard.”

The media narratives also had real policy impacts. In fact, President John F. Kennedy had declared Brazil’s northeast as a top priority in the Alliance for Progress, a ten-year “economic cooperation” program proposed in 1961 to counter the influence of the young Cuban Revolution in Latin America. On July 15, 1961, Kennedy declared that no area is in “more urgent need of attention than Brazil’s vast Northeast,” and established a USAID mission there the following year. By 1963, this mission had over 133 U.S. technicians employed in the city of Recife alone. The capital of Pernambuco state, hometown of Julião and where the Peasant Leagues were founded, received high level visits from U.S. officials, from Peace Corps Director Sargent Shriver to then-professor Henry Kissinger, ex-presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, and Food for Peace director George McGovern.8 In 1961, the American Broadcasting Company sent filmmaker Helen Jean Rogers, who had links to the Central Intelligence Agency, to produce a documentary on the Peasant Leagues entitled Brazil: The Troubled Land, broadcast on public television in 1961, and released as a film in 1964, the year of the coup.9

Throughout the media coverage, China and the Chinese Revolution were looming specters over the Brazilian northeast. In the opening scene of Brazil: The Troubled Land, the black-and-white documentary shows Francisco Julião giving a passionate speech at a rally, wagging his finger next to a lit torch. “This is Francisco Julião of Brazil. You may not have heard his name, but learn it,” the narrator begins. “Juliao is the most important peasant leader in Latin America, and the peasants are the great majority, more than one hundred million. He is a follower of Fidel Castro and Mao Zedong, enemies of the United States.… This is the story of Northeast Brazil, of Franscisco Julião, and the peasants he woos in Latin America. Brazil, the troubled land,”10 As a recurrent narrative in the media reports, Julião was referred to in the same breath as Communist leaders Castro and Mao, who were not only portrayed as predators of poor peasants but were “enemies of the United States,” turning this arid and impoverished region—and the struggle for land reform in Brazil—into a U.S. foreign policy problem.

Castro and Mao may have been considered enemies of U.S. imperialism, but to peasants around the world—Brazil included—they were seen as inspirational figures who were leading successful revolutions. “Fidel [and] Mao are represented as heroes here, imitated by the Northeast’s peasant workers and students,” Szulc wrote in his New York Times front-page article in 1960.11 He added that Julião is “currently visiting Communist China” and that “invitations to visit China are likewise being received by the Northeast’s intellectual, political and student leaders,” an observation that was not far from reality.

From João Goulart to Jorge Amado: The People’s Diplomacy between China and Brazil

People-to-People Diplomacy

Since the PRC was established in 1949, it had been placed under heavy diplomatic and economic blockades, led by the United States, a tactic that the hegemon continues to use against one quarter of the countries in the world today.12 Over a decade into PRC’s existence, it had formal relations with less than three dozen countries, with Cuba being the only country in the Americas that recognized the PRC a year after its own revolution. In this context, “people’s diplomacy” (人民外交, renmin waijiao) and “people-to-people diplomacy” (民间外交, minjian waijiao) became the principal, if unofficial, international relations strategy of the PRC. Under the guidance of premier Zhou Enlai, popular diplomacy aimed to build relationships with organizations friendly to China, principally through trade and cultural exchanges that bypassed the sanctions.13 Building bilateral friendship associations were key to building people-to-people relationships. In Latin America, the first friendship association was founded in 1952 in Chile, supported by important figures such as future president Salvador Allende. These organizations organized events and facilitated the trips on both sides of the Pacific, including delegations of journalists, artists, intellectuals, acrobatic troupes, and trade specialists, among others.

In Brazil, the Brazil-China Friendship Association was founded in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1953 and 1954, respectively. Amongst the many activities, the first Chinese delegations to Brazil included one in 1955 that aimed to establish direct trade between China and Latin American countries, and another in 1956 of a Chinese folk art performance troupe.14 Contrary to the West’s attempts to isolate the newly founded Communist state, the PRC had established a vibrant popular diplomacy in concert with peoples and countries of the Third World. According to some U.S. accounts, between 1949 to 1960, over 1,500 Latin Americans visited China, including hundreds of people from Brazil.15 Among the notable Brazilian Communist visitors included Jorge Amado and Zelia Gattai in 1952 and 1957, Carlos Marighella in 1953–1954, Diógenes Arruda Câmara in 1956, and Luís Carlos Prestes in 1959, among others. At the end of the decade, the Cuban Revolution enabled a new tide in China-Latin American and Caribbean relations. In Havana, China established its first embassy in the western hemisphere in 1960, which further facilitated communication in the region. In 1959 and 1960 alone, China received over two hundred delegations from twenty-one Latin American and Caribbean countries and sent over twenty-four delegations to fifteen counterpart countries.16 It was in the context of increased political, economic, and cultural exchanges that Brazil’s then-vice president Goulart, as well as Julião, were invited to visit China.

Goulart arrived in Beijing on August 13, 1961, less than a month after Kennedy declared northeast Brazil the top priority in Latin America for the United States. Leading a Brazilian trade delegation, Goulart was received with the highest honors by Chinese leaders Mao, Zhou, and Liu Xiaoqi, among others, and toured Beijing, Hangzhou, and Guangdong province.17 He was the first and highest senior official from the continent to visit the PRC since its establishment. This drew the attention not only of Chinese people, but also of the United States. Contrary to the claims by the U.S. and the Brazilian right wing and military, Goulart was far from being a communist. However, he received wide support from leftist trade unions, political parties, and mass social movements such as the Peasant Leagues, and was open to establishing stronger ties with socialist countries. Reporting on his trip to China, the New York Times printed the headline “Goulart Admires Mao of Red China” and quoted him saying: “We do not hope that the Chinese people’s communes will collapse. On the contrary, we hope they will prosper, because the prosperity of the people’s communes means the prosperity of the Chinese People’s Republic. We hope the imperialists will be disappointed because their disappointment is what we like most.”18

As a key voice of the U.S. bourgeoisie, the New York Times was concerned about what this visit signaled, as Goulart was set to become the next head of state. In fact, it was during his thirty-one-day trip to the PRC, as well as to other Asian nations and the Soviet Union, that Brazilian president Jânio Quadros resigned after seven short months in office. Returning from his Asian tour, Goulart assumed the presidency, but with limited powers set by a new parliamentary system—a compromise with the conservative sectors and the military, which were already unnerved by Goulart’s left tendencies.19 In fact, as documented in Sílvio Tendler’s documenetary, Jango (1984), there were even plans proposed by the U.S. Air Force to shoot down Goulart’s plane upon entry into Brazilian airspace.

Among the cultural agreements made on Goulart’s visit to China was to send three Chinese journalists to Brazil, culminating in the establishment of the Brazilian offices of Xinhua News Agency in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo over the next two years.20 Meanwhile, the trade discussion focused on Brazil’s agricultural situation, which was structured around monoculture production geared for exports—as a means to access foreign exchange—and sold at unfavorable prices set by the U.S. markets.21 Establishing fairer trade relations with socialist countries was seen as a way for Brazil to overcome this dependency, a problem that continues to plague many countries of Latin America and the rest of the Global South, even after decades of formal independence from colonial rule. Addressing a mass rally in Beijing on August 17, Goulart said, “China under the leadership of the great leader Mao Zedong is a reality and an example that shows how a people, looked down upon by others for past centuries, can emancipate themselves from the yoke of their exploiters.”22

Emancipation from colonial, feudal, and capitalist exploitation were threads that united the Chinese and Brazilian people, and perhaps nowhere was the connection clearer than with peasant struggles of the northeast of Brazil. The northeast is known for its tradition of peasant culture, a place of traveling folk artists and musicians—violeiros, folhetinistas, and cantadores. Like the Communist Party of China did during the years leading up to the revolution, the Peasant Leagues collaborated closely with these cultural workers to conscientize the peasants and to build the organization, often adding political content to local traditional forms.23 In his investigations in the region, Szulc wrote, “the nomad singers of the Northeast, who once sang of the loves and the hatreds of the proud people here, now sing of land reform and of political themes.”24 He noted especially the following lyrics in the “Hymn to the Peasant”:

The sugar that we sell to capitalist America,

It serves to sweeten the milk of a Franco Spain.

For sure will serve the wine of the Socialist world.

What harm is there in a ship

Carrying our common Brazilian coffee

And selling it to a China

Where there is no Chiang Kai-shek.25

Songs such as these helped create a sense of cultural and political affinity between the Chinese Revolution, the mobilization of the Peasant Leagues, and the agricultural production of the Brazilian peasantry. Likewise, cultural and literary exchanges helped bring the struggles of the Brazilian countryside to China.

Rebellion in the Backlands

The Brazilian northeast entered the imaginary of the Chinese people soon after the establishment of the PRC, as part of the efforts to build understanding and solidarity amongst the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. As part of China’s popular diplomacy, literature and literary exchanges were seen as key in building a united struggle against imperialism, and the new socialist country made enormous efforts to translate literature from the Third World. It was in the context that the works of Amado, the Brazilian communist writer who won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1951, began to be translated into Chinese. Amado, who visited China three times in 1952, 1957, and 1987, was the most published Latin American writer in China from that period up until today.26

Amado’s novels Terras do Sem Fim (The Violent Land) and São Jorge do Ilhéus (The Golden Harvest), translated into Chinese in 1953 and 1954 respectively, brought the stories of land struggles in the cacao plantations of Bahia, the northeastern state where Amado hails from.27 He was also responsible for bringing, and even translating, Chinese novels to Brazilian audiences, most notably, the publication of Ding Ling’s The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River (O sol brilha sobre o rio Sangkan) in 1955. The novel, which won the second-degree Stalin Prize for literature by the Soviet Union in 1951, was the fruit of the eight years she spent working alongside peasants in the struggle for land reform in Shaanxi province in the lead up to the Chinese Revolution. In Brazil, it was published in the Coleção Romances do Povo (The People’s Novels Collection) under the direction of Amado by Editora Vitória, a publisher affiliated with the Communist Party of Brazil (PCB). Amado had been a long-time PCB member and was even elected as a federal deputy for São Paulo in 1946, shortly before the party was declared illegal again.

Beyond Amado’s novels, another important literary work in constructing the imaginary of the Brazilian northeast was Os Sertões (Rebellion in the Backlands) by Euclides da Cunha. In his acclaimed 1902 work of reportage literature, Cunha documented the bloody Canudos Massacre (1896–1897) in which the army of the young Brazilian Republic was sent to decimate a settlement and killing twenty-five thousand poor sertanejos, comprised of peasants, recently freed enslaved people, and Indigenous people of the northeast. This story resonated with China’s own bloody history of feudal and imperialist violence against the poor peasant masses. In 1959, on the fiftieth anniversary of Cunha’s death, the novel was translated into Chinese and a large memorial conference was held in China, with the presence of both Chinese and Brazilian writers. Despite the limitations of Chinese translators and critics in understanding the Brazilian reality, these novels helped construct an imaginary of Brazil’s revolutionary northeast, which was read alongside China’s revolution. Likewise, novels such as Ding’s helped introduce new understandings of the Chinese land reform and revolutionary process, though Brazilian interpretations also lacked adequate historical or cultural understanding.28

Nevertheless, these literary translations from Amado to Ding and political and cultural exchanges from Julião to Goulart were essential to strengthening people-to-people relations, and positioned the struggles for land reform and the protagonism of the peasantry as central connecting threads linking these distant lands and peoples.

In the Law or by Force: The Peasant Leagues and the Chinese Revolution

In the Law or by Force

July 26, 1964—the anniversary of the guerilla movement that brought Cuba to revolution—marked exactly one month since Julião was jailed by the new military regime. Os Sertões by Euclides da Cunha was one of the three books that he requested in jail, next to Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads), the Portuguese epic poem by Luís Vaz de Camões, and the Holy Bible, as he noted in his letter to his daughter written on that day.29 After making his final address at the National Congress as the coup unfolded, Julião spent three months in hiding in rural Goiás, under the pseudonym of Antonio Ferreira da Silva. He spent one and half years in jail, never receiving his copy of Os Sertões, and was freed through habeus corpus. He promptly went into exile in Mexico, where he stayed for the next fifteen years until the Amnesty Law of 1979 allowed the return of exiles.

Born in the northeastern state of Pernambuco, Julião did not come from a peasant background, but was the son and grandson of sugar plantation landowners. He entered the peasant struggle as a lawyer. Though there have been many peasant leagues organized in different regions and moments of Brazil’s history, including those associated with PCB, the Peasant Leagues began in Engenho Galiléia, sixty kilometers from the state capital of Recife. There, ten years before the coup, the peasants and agricultural workers formed the Agricultural and Livestock Society of Pernambuco Planters to confront exorbitant land rents, evictions, illiteracy, and the inability to bury their dead—problems exacerbated by the entry of capitalism into the countryside.30 With the legal support of Julião and through a fierce battle, the agricultural workers won their demands in 1959, leading to the expropriation the plantation into the hands of 140 families. This victory had incredible impact for the peasant struggle in the region and sent shockwaves to the latifundistas, or large plantation landowners in Brazil.

Around the country, the “Galileus” came to symbolize the northeastern peasant in the struggle against agricultural and capitalist exploitation.31 The rapid growth of the Peasant Leagues—which by 1962 had mobilized tens of thousands of members in over ten states; created its own newspaper, A Liga (The League); and attempted to build its own political party—also caught the interest of Chinese revolutionaries for obvious affinities.32 Julião visited China at least once during this period of intensive growth, though there was no Chinese media coverage of his visit(s).33 After the Cuban Revolution, Julião, along with his fellow leader of the Leagues and wife, Alexina Crespo, also visited Cuba several times. When faced with increased kidnapping threats, Crespo and their four children moved to Cuba to live and study in 1962, and where they learned of the news of the coup in their home country.34

Even though Julião did not publicly declare himself as a Communist, the Chinese and Cuban revolutions had a profound impact on his own thinking and strategic vision and he often referred to them in his writings and speeches.35 Beyond being a practicing lawyer, Julião was a writer and a poet; his first published book was a collection of his short stories called Cachaça, published in 1951. As a leader of the Peasant Leagues, he wrote several important and popular booklets that guided the peasant struggle, which could themselves be read as works of poetry. In A Cartilha do Camponês (1960) (The Peasant Booklet), Cuba and China are often passionately called upon to rally the peasants: “Your cruel enemy—the latifúndio—is not faring well, and I assure you that its illness is severe. There is no cure for it. It will die foaming at the mouth with rage like a mad dog. Or like an old lion that has lost its claws. It will die as it did in China, a country very similar to our Brazil. It will die as it died in Cuba where the great Fidel Castro gave each peasant a rifle and said: ‘Democracy is the government that arms its people.’ Peasant, I went there and saw everything.”36

Similar to how the novels of Amado and Cunha presented Brazil as a mirror to the Chinese reality, the prerevolutionary situation of the Chinese peasantry was also projected onto the land struggles in Brazil, particularly those in the northeast. The revolutions and land reform processes in China and Cuba, with the organized peasantry as protagonists, were portrayed as the eventual future of Brazil. Speaking of the tyranny, injustice, and misery brought on by the large landowning class, Julião wrote: “It was the union that ended all of it there in Cuba. The same was true for China. The same will also happen here in Brazil!” In his writings and speeches, the Cuban, Chinese, and Brazilian people not only shared a common history of colonial and feudal oppression, but also, inevitably, shared a common destiny.

In the opening pages of Quem São As Ligas Camponesas? (Who Are the Peasant Leagues?, 1963), written after visiting China, Julião paints a panorama of the class reality in the Brazilian countryside:

There are forty-five million human beings waiting for the dawn. There are twelve million labor sellers, bound to the field as if to perpetual galleys… This population is divided as follows: proletarians, semi-proletarians, and peasants. The proletarians are the wage earners. The semi-proletarians are the settlers, the laborers, the hired hands, the contractors. The peasants are the foreiros or tenants, the sharecroppers, the partners, the cowboys, the squatters, the waggoners, and the smallholders. All of them are shackled by a system of servitude.

Notably in this text, Julião introduces the term “semi-proletariat” to describe the agricultural workers who may have had access to limited land and means of production for subsistence farming, but relied at least partially on selling their labor power to survive. This new class of part worker, part peasant emerged with the capitalist expansion into the countryside, accelerated in this period. Interestingly, Julião’s writing bears striking resemblance to Mao’s Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society (1926), written when Mao was working in close contact with the self-organized peasant associations in Hunan province. This text pushed for and foreshadowed the Communist Party of China’s eventual turn from focusing on organizing the urban industrial workers to the peasant masses in the countryside. Mao calls the “semi-proletariat”—a term that he introduces in this text to distinguish agricultural workers from peasants—“our closest friends” in the revolutionary process.37 Distinct from Mao, however, Julião promoted the “legal and pacific” means for agrarian reform, focused on the three fronts of mobilizing in the countryside, in the judicial system, and in the legislative assembly.38 At times, however, he left his comments vague. For example, in the same booklet, Julião ended a chapter with the provocative line: “For a radical agrarian reform. In the law or by force. With flowers or with blood.”39

“In the law or by force” (“na lei ou na marra”) became an important slogan and rallying cry associated with the Peasant Leagues. Through which means agrarian reform would be won—or seized—was at the center of the agrarian question at the time. The First National Congress of Farmers and Agricultural Workers in Belo Horizonte in November 1961 brought together seven thousand people from twenty states to debate this very question. Participants included representatives from urban and rural organizations, notably the Peasant Leagues and the PCB-affiliated Union of Farmers and Agricultural Workers of Brazil, as well as politicians, including Goulart.40 It could be said that in this historic congress, the radical agrarian reform line, “in the law or by force,” that the Peasant Leagues spearheaded dominated the more reformist or legalistic line supported by the PCB. However, how by force would be understood within the Peasant Leagues themselves and in the greater movement for agrarian reform remained a subject of great debate.

I Asked Mao Zedong for Weapons

Julião, though the most publicly well-known figure of the Peasant Leagues, was also not the only senior leader of the Leagues to have visited China. While Julião headed the legal and institutional part of the Leagues, it was Crespo who was responsible for the underground work.41 Crespo, under the clandestine alias “Maria”—one of the most common women’s names in Brazil—was a guerilla warfare strategist, personal bodyguard to Julião, feminist leader, puppet theater artist, and mother of four. She was also married to Julião until 1963. Responsible for the international relations of the Leagues, Crespo received military training in Cuba, where she discussed the guerrilla strategy of Brazil with Che Guevara, Castro, and other Cuban leaders.42 She also met with the heads of states of socialist countries including Chile, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and the Soviet Union. With the support of Cuba in strategic planning and arms, the Leagues had organized at least eight dispositivos (military outposts or bases) in the country for guerilla training. Though there were different opinions regarding the direction of armed struggle in Brazil, the Leagues were among various organizations that had turned to armed struggle in the 1960s, before and after the military-led coup.

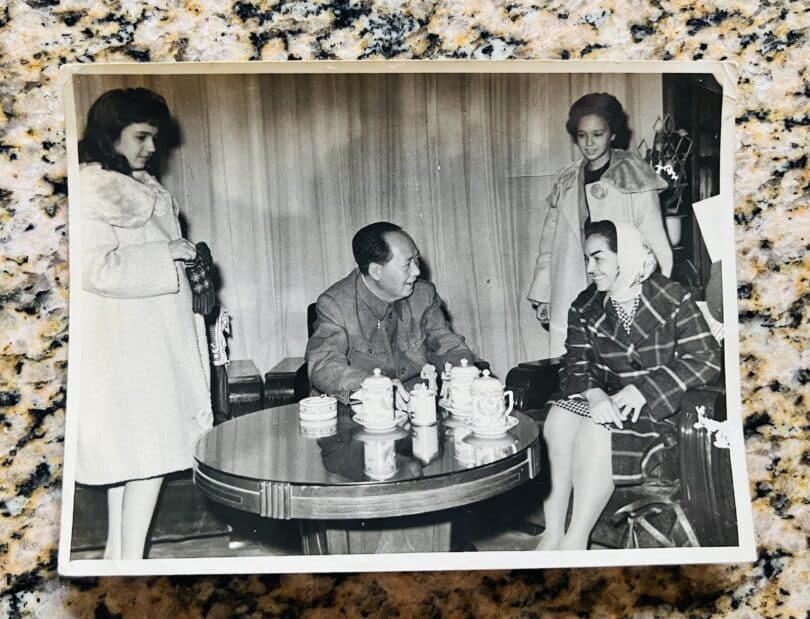

Responding to an interview question whether Julião, who was always against armed struggle, knew of her participation, Crespo said, “He knew, he knew. He stayed, let’s say, on the legal, institutional side, the speeches. And we stayed on the clandestine side, preparing things, training the peasants.”43 Among these preparations was a visit she made with her two daughters, Anatilde and Anatailde, in 1962 to China, and a personal meeting with Mao. Her daughters were on their way to the Soviet Union to study. This was arranged with the assistance of Cuba, where they had been living. Peking Review, an important magazine in China’s cultural diplomatic efforts, documented this visit with a photograph and a short note referring to the “cordial talk” between Mao and Crespo, “wife of Francisco Julião, president of the Peasant Leagues of northeastern Brazil, and her two daughters.”44 The trip was organized by the China-Latin American Friendship Association, whose president, Chu Tunan, had arranged a welcoming banquet and tour of China for their guests. It is perhaps one of the rare moments of such a high-level reception by PRC leaders for a woman from Latin America without an official organizational title or government affiliation who was traveling with her two daughters.

About the content of her “cordial talk” with Mao, Crespo had directly asked for Chinese support in the armed struggle of the Peasants Leagues. In an interview, she acknowledged: “Yes, I spoke in front of the girls. You had to seize the moment. If I managed to be received by him, I had to take advantage and say what needed to be said. I asked for support, he asked how many weapons we had. I said we had very little. He did not give an immediate answer, the Chinese are very cautious. Later, he sent a delegation of three comrades to check on the situation.”45

According to Crespo, the delegation did eventually arrive in Brazil, whom she received at the airport. After a conversation with Julião and another senior leader Clodomir Santos de Morais, the Chinese guests left. She suspected that the fact that Morais was imprisoned soon after the meeting caused the Chinese side back down in the end.46 After the coup, Crespo continued her political life in exile with her children; in Chile, she organized a front against the coup in Brazil; and in Sweden, where she lived for many years, she participated in an association of Brazilians exiled by the dictatorship. She would only return to Brazil in the early 1980s, after the Amnesty Law.47 Unfortunately, like many women revolutionaries, relatively little has been written about Crespo in comparison with Julião, and much of the history has been maintained and currently being compiled by her son Anacleto Julião and her great nephew.

The Struggle for Agrarian Reform: From the Old Cold War to the New Cold War

Until Wednesday, Isabela!

Brazilian communists or suspected ones, like Julião, were not the only ones to be imprisoned by the post-coup government. On April 3, 1964, two days after the coup, nine Chinese nationals were arrested in Brazil, including seven trade representatives and two Xinhua correspondents—the very ones that Goulart had agreed to receive in Brazil during his visit to China. They were accused of “subversion of Brazil” and “espionage” based on loose evidence that included a rolodex of the names of Brazilian military officers allegedly marked “to be killed, hanged, shot, or drowned.”48 The Chinese calls for solidarity with the prisoners were closely mapped by the CIA. In its report, “Protest, Condemn, Demand: A World-wide Chinese Communist Propaganda Operation Directed Against Brazil,” every organization and country that China had sent a “brotherly message” to regarding the arrests was traced. These messages were framed as “anti-Brazil” propaganda. In the New Cold War era, these anti-Communist narratives—which continue to be used as stories of Chinese nationals, especially in the United States and other Global North countries—being accused of or jailed for espionage become increasingly commonplace. In April of this year, the Brazilian government finally recognized the political amnesty of the nine Chinese nationals, only one of whom still is alive today.49

While under his own harsh prison conditions, Julião was able to write a letter to his newborn daughter, Isabela, on scraps of paper eventually smuggled out into the world. People risked their lives to reproduce and share this letter—a poem of hope to the peasantry—later published as Até quarta, Isabela! (Until Wednesday, Isabela!). Addressing his daughter, he reflected on the human dignity denied when a person is refused a spoon in prison, remembering his times in China, when he learned to eat with chopsticks, which he called his “indispensable comrades.”50 Despite the attempts to brutalize, humiliate, and crush the human spirit and the organized popular forces, Julião affirmed the continuity of the struggle:

But there’s one thing that never stops: the stomach. This organ lives in perpetual motion. If it could be abolished, peace would already have been established on Earth. Ever since we became aware that the first condition to sustain life is to fight against hunger, we have been fighting just for that. The stomach is closer to the earth than our feet…. Hence, the class struggle, which is not a Marxist invention, but an imposition of the stomach.51

Sixty years after the military coup, fifty years since the establishment of diplomatic ties between Brazil and China, and nearly forty years since the re-establishment of democracy in Brazil, the fight against hunger continues, as does the struggle for agrarian reform. Today, in one of the largest agricultural producing countries in the world, seventy million people are food insecure, while ten million people face hunger and malnutrition.52 The country has one of the highest land concentrations in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 0.86 for inequality in land distribution, mostly notably in the northeast, north, and central-west regions.53 The northeast also largest number of small-scale family farmers, but has the lowest levels of access to farming machinery, with less than 3 percent mechanization rate compared with the national average that is less than 14 percent, and China at 73 percent.54 The world is very different from sixty years ago, however many of the problems faced by the peasants and the poor in Brazil remain the same.

Today, we live in a historic moment different from the pervasive revolutionary anticolonial struggles of the 1950 and ’60s, and the fight for national sovereignty takes on different forms. Finding independent pathways out of underdevelopment for Global South countries includes building multilateral institutions like BRICS, championed by both China and Brazil. Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva knows this path will not be easy. He himself was imprisoned for 580 days in a lawfare collusion between the interests of U.S. imperialism and sectors of the Brazilian bourgeoisie and military, who disapproved of the Lula-initiated social and economic policies that uplifted millions of poor Brazilians, the increasingly assertive geopolitical role the country played, and the discovery of major “pre-salt” oil and gas reserves by the state-owned Petrobras. In an interview with Chinese media Guancha in 2022, Lula criticized the well-worn tactic of U.S.-backed coups that have prevented the development of Latin American countries. “It is not possible that Latin America was born to be poor. It is not possible that every time a country in Latin America starts to grow, there is a coup, and this coup always involves someone from the United States, there is always a United States ambassador involved.”55 When asked by the interviewer Eric Li why other BRICS countries had low economic development in comparison with China. “Because China has a party, China was the result of a revolution in 1949 by president Mao,” he responded. “China has a party that has power, has a strong state, that makes decisions and people fulfill them—what we do not have here in Brazil.”56 For these comments, the bourgeois media attacked Lula for wanting to install a “Chinese dictatorship” and “communism” in Brazil. Similarly, former president Dilma Rouseff, who was jailed and tortured by the military dictatorship and lost her presidency in a lawfare coup in 2016, faced media backlash for asserting a position of nonalignment with the United States in a lecture that she gave, “Our place is not with the United States, but in independence, alongside China.”57 Sixty years on, we see the same class forces using the same Cold War narratives as those thrown against Goulart and Julião in the 1960s.

Struggle! Build a People’s Agrarian Reform!58

As Julião wrote from prison, however, class struggle never stops; it is an imposition of the stomach. As long as there is hunger, there will be class struggle. This year marks another historic anniversary, which is the founding the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) forty years ago, born out of the embers of the military dictatorship and in the legacy of the Peasant Leagues, along with the Basic Ecclesial Communities and liberation theology of the Catholic church. MST, the largest social movement in Latin America, organizes over two million peasant and rural workers in twenty-four states. They see the process of the occupation and expropriation of underutilized lands, protected by the Constitution of Brazil, as way to build working class power, produce healthy food through agroecology, fight for agrarian reform, push for social transformation of the country, and build internationalism. Through four decades of struggle, the MST has won land for 450,000 families now living in settlements, with another 90,000 in encampments. Inevitably, these victories of the organized working class upset the Brazilian bourgeoisie.

In fact, last year, a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry, made up of far-right parliamentarians, opened an “investigation” into the MST, in which none of the accusations were proven. During the seven-hour testimony, MST national leader João Pedro Stedile was questioned about his relationship with China after having visited the country as part of Lula’s official delegation in April 2023. When asked whether there was a Chinese organizational equivalent to the MST, Stedile responded, “No, because in 1949 they carried out agrarian reform. [For] those of you who so desperately want to defeat the MST, the formula is simple: carry out agrarian reform and the next day the MST will disappear.”59

This year, the MST, in cooperation with various Chinese and Brazilian partners began bringing Chinese machinery for small-scale producers to the northeastern countryside. This was the fruit of an agreement between the Northeast Consortium, the China Agricultural University, the Association of Machinery Producers in China, and Baobab—International Association for Popular Cooperation, which allowed for the implementation of the Brazil-China Demonstration Unit for Agricultural Cooperation and Development.60 According to Stedile, Brazil’s agricultural machinery sector is controlled by an “oligopoly of three transnational companies” that produces machinery that serves the large agribusiness rather than family farming. Unlike agribusiness, which only produces commodities for export, small-scale family farmers, including the families of the MST, produce food that feeds the people. The machinery cooperation with China, which is the largest producer of machinery for small-scale farming, is a “strategic alliance” to create future joint-venture factories in Brazil that ensures the transfer of Chinese technology in the Brazilian countryside.61 This could have the potential of reshaping the industrial development and agricultural mode of production in Brazil, as well as the question of hunger and food security. Today, compared with the early socialist period, China prefers to export development rather than communist ideology—machinery and technology rather than guns—but this cooperation marks another chapter in the decades-long story between China and Brazil to the still unresolved agrarian question.

Notes

1. The term civil-military coup emphasizes the collaboration between the military forces and sectors of the Brazilian bourgeoisie in the 1949 coup d’état in Brazil.

2. Francisco Julião, “Discurso do deputado Francisco Julião em 31 de março de 1964 na Câmara dos Deputados,” Arquivo Nacional do Ministério da Gestão e da Inovação em Serviços Públicos, March 31, 1964.

3. Boris Fausto, História do Brasil (São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2004), 459.

4. Tad Szulc, “Washington Sends ‘Warmest’ Wishes to Brazil’s Leader,” New York Times, April 2, 1964.

5. Anthony W. Pereira, “The US Role in the 1964 Coup in Brazil: A Reassessment,” Bulletin of Latin American Research 37 (2018): 5–17.

6. Maria Rita Kehl, “Camponese e Indígenas no Relatório da Comissão da Verdade,” RMBA-Medo (2017): 148–49.

7. Tad Szulc, “Northeast Brazil Poverty Breeds Threat of a Revolt,” New York Times, October 31, 1960.

8. Anthony W. Pereira, “God, the Devil, and Development in Northeast Brazil,” PRAXIS: The Fletcher Journal of Development Studies XV (1999): 119.

9. Urariano Mota, “‘Brazil: The Troubled Land’ ou A cineasta que veio da CIA,” Jornal GGN, November 13, 2015; Karen M. Paget, Patriotic Betrayal: The Inside Story of the CIA’s Secret Campaign to Enroll American Students in the Crusade Against Communism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

10. “Brazil: The Troubled Land,” documentary by Helen Jean Rogers, American Broadcasting Company, 1961.

11. Szulc, “Northeast Brazil Poverty Breeds Threat of a Revolt.”

12. Francisco R. Rodríguez, “The Human Consequences of Economic Sanctions,” Centre for Economic Policy Research, May 4, 2023.

13. Huang Zhiliang, Xin da lu de zai fa xian: Zhou Enlai yu lading meizhou (Beijing: World Knowledge Publishing House, 2003), 60.

14. Huang, Xin da lu de zai fa xian, 62–65.

15. William E. Ratliff, “Chinese Communist Popular Diplomacy toward Latin America, 1949–1960,” Hispanic American Historical Review 49, no. 1 (1969): 57–58; Wang Siwei, “Transcontinental Revolutionary Imagination: Literary Translation between China and Brazil (1952–1964),” Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 6, no. 1 (January 2019): 74.

16. Cecil Johnson, Communist China and Latin America 1959–1967 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), 22.

17. Cecil Johnson, “Jango pediu que sua viagem à China fosse autorizada por escrito,” Sul 21, May 10, 2011.

18. Cecil Johnson, “Goulart Admires Mao of Red China,” New York Times. August 27, 1961.

19. Fausto, História do Brasil, 442.

20. Celiane Ferreira da Costa, “Análise das relações sino-brasileiras a partir da prisão de nove chineses no início do governo militar (1964),” Ideias 9, no. 2 (July–December 2018): 15–24.

21. Johnson, Communist China and Latin America 1959–1967, 27.

22. Johnson, Communist China and Latin America 1959–1967, 28.

23. “Go to Yan’an: Culture and National Liberation,” Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, May 16, 2022.

24. Tad Szulc, “Marxists Are Organizing Peasants in Brazil,” New York Times. November 1, 1960.

25. Chiang Kai-shek was the head of the Nationalist Kuomintang and the Republic of China in mainland China from 1928 to 1949. After the Communist victory, Chiang and his forces moved to Taiwan.

26. Fan Xing, “Tradução literária Como construção Da Identidade Cultural: A tradução Da Literatura Brasileira Na China Entre 1919 E 1966,” Cadernos De Tradução 43 (2023): 136.

27. Xing, “Tradução literária Como construção Da Identidade Cultural”: 146.

28. Wang, “Transcontinental Revolutionary Imagination,” 95.

29. Francisco Julião, Até Quarta, Isabela (Recife: Bagaço, 2015), 67.

30. Elide Rugai Bastos, As Ligas Camponesas (Petrópolis: Vozes, 1984), 11

31. Bastos, As Ligas Camponesas, 18.

32. Elide Rugai Bastos, “História das Ligas Camponesas,” Memorial das Ligas e Lutas Camponesas, n.d.

33. Johnson, Communist China and Latin America 1959–1967, 19.

34. Leonilde Servolo de Medeiros, “Julião, Francisco,” Diccionario biográfico de las izquierdas latino-americanas, diccionario.cedinci.org.

35. Francisco Julião interviewed by Geneton Moraes Neto, “Um depoimento para a história: O homen que agitou os canavais (1983),” Marxists Internet Archive.

36. Francisco Julião, A Cartilha do Camponês (Recife: Ligas Camponeses, 1960), 3.

37. Mao Zedong, “Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society (March 1926),” Marxists Internet Archive.

38. Francisco Julião, Que São As Ligas Camponesas? (Rio de Janeiro: Editôra Civilização Brasileira, 1962), 27.

39. Julião, Que São As Ligas Camponesas?, 49.

40. Instituto Perseu Abramo, ”Reforma agrária, na lei ou na marra,” Memorial da Democracia.

41. Memórias Clandestinas, documentary by Maria Thereza Azevedo (2004).

42. Gabral Gomes, Maria da Glória Dias Medeiros, and Antônio Henrique da Silva Araújo, “Lugar de mulher é na revolução: confissões de uma clandestina,” V Colóquio de História (2011): 1207–9.

43.João Pedro Stedile, A Questão Agrária no Brasil: História e natureza das Ligas Camponesas: 1954–1964 (São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2nd ed., 2012), 179.

44. “Chairman Mao Receives Brazilian Guests,” Peking Review 5, no. 27, April 27, 1962, 22.

45. Stedile, A Questão Agrária no Brasil, 181.

46. Stedile, A Questão Agrária no Brasil, 182.

47. Gomes et al., “Lugar de mulher é na revolução,” 1209–10.

48. “Frame-Up in Brazil: Fresh Exposures,” Peking Review 7, no. 23, June 5, 1964, 17–19.

49. Iara Vidal, “60 anos depois, Brasil reconhece nove chineses presos pela ditadura como anistiados políticos,” Forum, April 3, 2024.

50. Julião, Até Quarta, Isabela, 42.

51. Julião, Até Quarta, Isabela, 64.

52. UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023 (Rome: FAO, 2023).

53. Lays Furtado, “São muitas terras em poucas mãos,” Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, October 1, 2020.

54. Mauro Ramos, “Máquinas chinesas para a agricultura familiar estão a caminho do Nordeste,” Brasil de Fato, November 6, 2023.

55. Rede TVT, “Entrevista de Lula para Guancha, jornal chinês,” YouTube video, July 8, 2021.

56. Rede TVT, “Entrevista de Lula para Guancha, jornal chinês.”

57. Marcelo Hailer, “Dilma Rouseff: ‘Nosso lugar não está com os EUA, nosso lugar é a independência, junto com a China,” Forum, August 13, 2021.

58. Official slogan of the Sixth National Congress of the MST that took place in Brasilia in February 2014.

59. Cristiane Sampaio, “Veja os destaques do depoimento de João Pedro Stedile na CPI do MST,” Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, August 13, 2023.

60. Redação RBA, “Consórcio Nordeste e China firmam acordo para beneficiar agricultura familiar,” Rede Atual Brasil, September 16, 2023; “Máquinas chinesas destinadas à agricultura familiar serão lançadas nesta sexta (2) no RN,” Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, February 1, 2024.

61. João Pedro Stedile, “Agricultura familiar precisa ser mecanizada,” Folha de São Paulo, March 22, 2024.