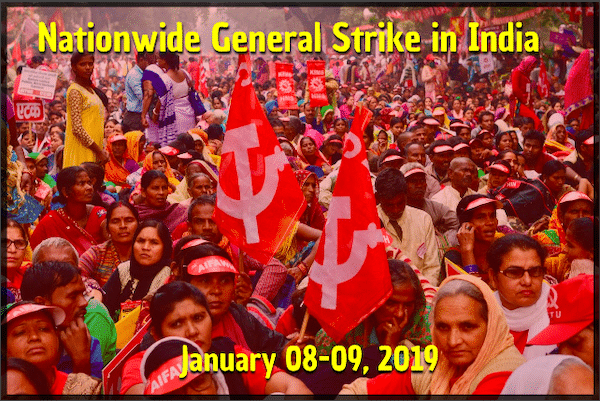

Workers across India are participating in a two-day nationwide strike on January 8 and 9. The strike has been called for by 10 of the largest trade unions in the country. A one-day nationwide strike called by the same trade unions in 2016 had over 180 million participants, and was the largest mobilization of workers at that time. This time, over 200 million workers are likely to participate. The strike is being held just a few months away from the parliamentary elections, during which the incumbent right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party-led government under prime minister Narendra Modi is vying for a second term.

Who is organizing the strike?

The strike is being organized by 10 central trade union organizations (CTUOs), viz., Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), Centre for Indian Trade Unions (CITU), Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS), Trade Unions Coordination Centre (TUCC), Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), All India Central Council of Trade Unions (AICCTU), Labour Progressive Federation (LPF), United Trade Union Congress (UTUC), and All India United Trade Union Centre (AIUTUC).

These are national union federations, which are among the largest mobilizers of workers in India, and represent most of the organized labor in the country. Many of them are associated with different political parties, mostly among those in the opposition, with varying degrees of autonomy. In the current strike, only one CTUO, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), a sister organization of the ruling BJP, is staying away.

What are the demands of the strike?

The immediate trigger of the strike was the Trade Unions Amendment Bill, 2018, proposed by the Modi government in August last year. While the Bill proposes to give statutory recognition to labor unions from both the State and central government, it also seeks to give the respective governments wide-ranging discretionary powers in making that decision. The Bill also gives no standard criteria for this recognition. Neither does it reference the previously existing norms, like the kind used to recognize a CTUO. This goes against the established practices as agreed upon in tripartite (employer, employee and government) consultations in the past. This also threatens the precious little scope for workers’ organization in India. The proposal of the Bill prompted the 10 unions to jointly declare the national strike on September 28, 2018.

But on a larger scale, the trade unions have put forward a 12-point charter of demands before the government as part of their strike. The demands range from raising the monthly minimum wage to Rs. 18,000, and securing and protecting the public sector to matters of price rise and food security. The charter specifically includes preventing foreign or private involvement in some of the key public sector enterprises in the country, including defense manufacturing, railways and other public transport, and banking and finance. They have also targeted proposals by the government to amend or alter the existing laws and codes on labor rights and trade unions. Many of these proposals aim to make conditions “easier” for businesses. The trade unions have also called for the protection of rights of the large population of informal workers and to immediately address the agrarian crisis that has been plaguing the nation.

What is the condition of labor and employment in India?

India has a workforce of over 520 million, only 6-7% of whom are employed in formal enterprises, of which barely 2% of are unionized. Most of the unionization is limited to public sector employees, with very few instances of a formal union being active within the private sector or informal sector. In the last Employment and Unemployment Survey to be conducted by the government in 2012, over 62% of the employed were estimated to be daily wage workers, making their source of income seasonal and very vulnerable to market fluctuations. There is very little to indicate that things have changed radically in the past seven years. If anything, the very nature of unorganized labor has changed. Those dispossessed by the agrarian crisis that has been plaguing rural India since the mid-1990s, have taken to migrating to urban centers in search of livelihoods. According to the last census conducted in 2011, more than 450 million Indians were migrants to other regions, usually to urban centers, accounting for 37% of the population. If not all, a majority of them migrated to a different place for livelihoods. Most of them migrate to work only for short periods of time, not only making any meaningful organizing of this group extremely difficult but also making them very vulnerable to exploitation.

India also has among the lowest average wages in the world. In 2018, the average monthly wage was estimated to hover around Rs. 7,000 (USD 100). For those in the informal sector, the amount is around Rs. 4,500 (USD 64). Moreover, employment generation under the present BJP government has been abysmally low. In a country where over 13 million people enter the job market annually, the government, by its own estimates, was only able to raise around 400,000 jobs in the first three years of its tenure, between 2014 and 2017. A new study by a private think tank estimated that India lost around 11 million jobs in 2018, making it the worst performing year in employment generation for India, after decades.

What is the stance of the unions towards the present government?

In a press conference held on January 7, leaders of the 10 trade unions highlighted the government’s attitude towards unions in general. The strike was announced in September, but the government did not reach out to the unions for negotiations. In fact, the government sidelining the unions is a long-standing problem. Earlier in July 2018, the Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), a CTUO affiliated to the largest opposition party, the Indian National Congress, was taken out of tripartite consultations over internal disputes in its leadership. Ever since then, all the national trade unions, except the BMS, began a boycott of the tripartite consultations which they lambasted as a “little more than a formality”. The relationship between the government and trade unions has paralleled the souring and increasingly competitive relationship that the government has right now with the opposition. While the strike in many ways was an inevitable outcome of the acrimony between the government, opposition and the trade unions, it really goes beyond that.

What are the reactions so far to the strike?

Most national media houses, especially TV news channels, are yet to begin covering the strike and have chosen to focus on other issues. Even the government has presented itself as indifferent, but the strike has visibly rattled the ruling dispensation. In the national capital and the neighboring state of Haryana, the atrocious Emergency Services Maintenance Act (ESMA) was imposed on transport workers and other government employees, preventing them from participating in the strike. In other States, like West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, the State governments denied permission to workers to carry out the strike.

On the other hand, farmers and agricultural workers across India have extended their support, with organizations like the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) and All India Agricultural Workers’ Union (AIAWU) declaring a “rural strike” in support. Student unions and organizations in several prominent universities have offered their support and have volunteered to raise awareness about the strike and the conditions of the working class.

The strike, by and large, has remained peaceful, but confrontations between officials and protesters have been reported in many places. Arrests and detainment of union leaders have also been reported. Nevertheless, in several States, the strike has received wide support from the people. All of this is only as the day settles in. It remains to be seen how the ruling classes will react as the strike rolls out.