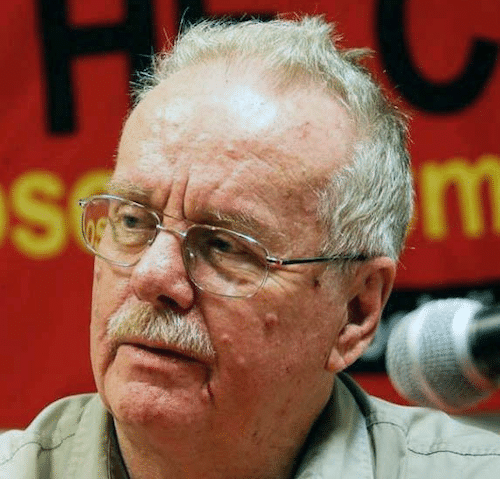

In an interview with roape.net, ecosocialist and writer Ian Angus discusses the environmental crisis, the Anthropocene and Covid-19. He argues that new viruses, bacteria and parasites spread from wildlife to humans because capital is bulldozing primary forests, replacing them with profitable monocultures. Ecosocialists must patiently explain that permanent solutions will not be possible so long as capital rules the Earth.

Can you tell readers of ROAPE about yourself? Your background, life, activism and politics etc.

I was born in Canada and have lived here for my entire life. As a teenager, I was inspired by the Cuban and Vietnamese revolutions, and became active in the Marxist left while still a student. I helped organize anti-war demonstrations and support for Latin American refugees in the 1960s and 1970s, and I wrote frequently for socialist publications in Canada and the U.S. My first book, published in 1981, was Canadian Bolsheviks, a history of the early years of the Communist Party of Canada.

Can you explain how, as a socialist and Marxist, you became aware of climate change for the first time? What were the books, events and issues, that first drew your attention to the issues?

I have always been deeply interested in science, so I have followed environmental issues for a long time—I’m really not sure when I first thought about climate change as a particular concern. However, in the 1990s I became interested in the discussions and debates about the possibility of a specifically Marxist analysis of the global environmental crisis. I read books and articles by a wide variety of green and red scholars, and for some time I was sympathetic to the view that Marx and Engels didn’t have much to say about nature, and that what they did say was inadequate or even wrong.

My ‘Eureka!’ moment was reading Marx’s Ecology, by John Bellamy Foster. Unlike other writers, Foster went back to the basics, showing in detail what Marx actually said about capitalism’s assaults on the natural world, and how it related to his materialist worldview. Marx analysed the great environmental crisis of his time—the decline of soil fertility in England and Europe—and identified its source as a capital-driven rupture in what he called the ‘universal metabolism of nature.’ As Foster showed, that concept of ‘metabolic rift’ provides an indispensable framework for understanding today’s ecological crises.

I was completely convinced by that analysis, and by the related work of Paul Burkett in Marx and Nature. After writing a number of articles on environmental issues, I started the online journal Climate & Capitalism in 2007, and in the same year helped to establish the Ecosocialist International Network (EIN). With Michael Löwy and Joel Kovel, I co-wrote the Second Ecosocialist Manifesto (also called the Belem Ecosocialist Declaration), in 2008. The EIN was short-lived, but it was an important first step: I think that the recently formed Global Ecosocialist Network will further advance the cause of building the mass movements we need.

A few years ago, you wrote Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System, can you talk about the arguments in the book, the concept of the Anthropocene, marking a new historical and geological epoch?

In the past few decades, scientific understanding of our planet has radically changed. A growing body of research has focused not just on individual environmental problems, but on the planet as a whole, and has shown that the Earth System is changing rapidly, in fundamental ways. The environmental conditions that prevailed since the last ice age—the only conditions in which human civilizations have existed—are now being swept away. Climate change is the most obvious example—the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere now is much higher than at any time in the last two million years. That, along with many other radical shifts led many scientists to the conclusion that a new epoch in Earth System has begun. They call the new epoch the Anthropocene, and there is wide agreement that the decisive shift to new conditions occurred in the middle of the 20th century.

In Facing the Anthropocene, I tried to show how major changes in capitalism during and after World War II caused the global changes that scientists have identified. In essence, the metabolic rift that Marx identified has become an interrelated set of global rifts, immense breaks in Earth’s life support systems.

This global, all-encompassing crisis is the most important issue of our time. There was a time when socialists could legitimately treat environmental damage as just one of many capitalist problems, but that is no longer true. Fighting to limit the damage caused by capitalism today and then building socialism in Anthropocene conditions will involve challenges that no twentieth century socialist ever imagined. Understanding and preparing for those challenges must now be at the top of the socialist agenda.

I must say that I’ve been very pleased by the response to Facing the Anthropocene. It’s now in its third printing, it has been adopted as a required reading in many university-level environment courses, and it has been translated into several other languages.

There has been much talk of a Green New Deal, that harks back to public work programmes, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by the U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s. A similar radical ‘Green’ deal, we are told, needs to be enacted, presumably mobilising all the resources of the states to avoid an environmental catastrophe. What is your opinion about these proposals, advocated by Naomi Klein and other radical environmentalists?

In the United States, where the term originated, the label ‘Green New Deal’ is being used by a wide variety of politicians and activists for a wide range of proposals. Green New Deal plans range from liberal tax reforms to social democratic welfare plans, in some cases including nationalization of energy industries. Still other versions are promoted in other countries, particularly Canada and Britain. None of them challenges the capitalist system as such, but apart from that it is difficult to make general statements about their content—you have to know which plan is meant.

The details are important, but much more important, in my view, is whether a GND plan can help mobilize people outside of the corridors of power. In Marx’s words, ‘Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programs.’ And as Naomi Klein says, ‘Only mass social movements can save us now.’

What we actually see from most politicians and NGOs, however, are top-down plans geared to persuading politicians and public officials, treating extra-parliamentary action as a sideshow, or steering it to electoral support for liberal politicians. That’s a formula for defeat. If that’s all a Green New Deal is, it’s just paper.

Having said that, the growing interest in green solutions is a positive sign. A few years ago, it would have been impossible for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez [an American politician and activist] to get a hearing for her version of GND, let alone get it endorsed by other elected officials and seriously debated in the press and elsewhere. That won’t win the changes we need, but it shows that some of our rulers are starting to feel the heat of mass protests. So even if not intended by the authors, the idea of a Green New Deal may help to bring people into the streets.

ROAPE is a radical review and website on political economy, focused on Africa. Can you talk a little about the extent of the climate crisis on the continent–and the Global South more generally?

There’s a chapter in Facing the Anthropocene titled ‘We are not all in this together.’ The continuing brutal assault on Africa is clear evidence of that. The people and countries who bear the least responsibility for global warming are already its biggest victims. It’s a green cliché that we are all passengers on Spaceship Earth, but in reality a few passengers travel first-class, with reserved seats in the very best lifeboats, while the majority are on wooden benches exposed to the elements, with no lifeboats at all. Environmental apartheid is business as usual in the Anthropocene.

If fossil capitalism remains dominant, the Anthropocene will be a new dark age of barbarous rule by a few and barbaric suffering for most, particularly in the Global South. That’s why the masthead of Climate & Capitalism carries a slogan adapted from Rosa Luxemburg’s famous call for resistance to impending disaster in the First World War: ‘Ecosocialism or barbarism: There is no third way.’

Militant environmental activism shook the world last year, much of this led by school children, in strikes and protests. Can you speak about the role and importance of activism, and how these movements need to be linked to wider groups and an anti-capitalist politics?

As I’ve said, the task before us is to mobilize mass movements in the streets, outside the corridors of power. We should expect that those movements won’t be perfect, and they will take unexpected forms. No one I know of predicted the size of the global youth climate strike movement that Greta Thunberg initiated, or the impact of the Extinction Rebellion movement in Britain, but both are powerful examples of what must be done.

In Canada, the most effective mass campaigns are being led by indigenous people fighting to protect their traditional lands from exploitation by the oil and gas industry. Recently, their protests and blockades effectively shut down the country’s main rail lines, forcing the government to negotiate with the Wet’suwet’en people, who are fighting to keep a natural gas pipeline off their land.

In these situations, the worst thing that socialists can do—and unfortunately some radicals do exactly this—is to stand aside, criticizing the real movement because its demands aren’t radical enough or because the protestors have illusions about what’s possible within the existing system. We need to remember Marx’s famous insight that masses of people don’t change their ideas and then change the world—they change their ideas BY changing the world.

Ecosocialists need to be active participants in and builders of the real movement—and as we do that, we must patiently explain the need for radical change, showing that the global environmental crisis is actually a global crisis of capitalism, and permanent solutions will not be possible so long as capital rules the Earth.

Next to my desk, I have Gramsci’s famous aphorism, Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will, because for me it defines what the ecosocialist attitude must be in our time. Capitalism is powerful, and we know that disaster is possible, but we cannot surrender to despair. If we fight, we may lose; if we don’t fight, we will lose. A conscious and collective struggle to stop capitalism’s hell-bound train is our only hope for a better world.

Many people are drawing the link between the climate crisis, capitalism and Covid-19 outbreak. Could you describe how, in your opinion, these issues are intimately linked?

Three years ago, the World Health Organization urged public health agencies to prepare for what they called ‘Disease X’—the probable emergence of a new pathogen that would cause a global epidemic. None of the rich countries responded, they just continued their neoliberal austerity policies, slashing investments in medical research and health care. Even now, when Disease X has arrived, governments are spending more to rescue banks and oil companies than on saving lives.

New zoonotic diseases—viruses, bacteria and parasites that spread from wildlife to domestic animals and humans—are emerging around the world, because capital is bulldozing primary forests, replacing them with profitable monocultures. In the destabilized ecosystems that result, there are ever more opportunities for diseases like Ebola, Zika, Swine Fever, new influenzas, and now Covid-19 to infect nearby communities.

Global warming makes it worse, by allowing (or forcing) pathogens to leave isolated areas where they may have existed, unnoticed, for centuries or longer. Climate change also weakens the immune systems of people and animals, making them more vulnerable to diseases and more likely to experience extreme complications.

In short, capitalism puts profit before people, and that is killing us.