PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP’S executive order banning Americans from using TikTok is driven by concerns that the company might hand over user data to Chinese authorities. Recently hacked police documents reveal the nature of the company’s relationship to law enforcement–not in China but in the United States.

TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, is headquartered in Beijing, where the government censors social media content and maintains other forms of influence over tech companies. But a glimpse at what TikTok does in the U.S. underscores that data privacy issues extend beyond China.

Documents published in the BlueLeaks trove, which was hacked by someone claiming a connection to Anonymous and published by the transparency collective Distributed Denial of Secrets, show the information that TikTok shared with U.S. law enforcement in dozens of cases. Experts familiar with law enforcement requests say that what TikTok collects and hands over is not significantly more than what companies like Amazon, Facebook, or Google regularly provide, but that’s because U.S. tech companies collect and hand over a lot of information.

The documents also reveal that two representatives with bytedance.com email addresses registered on the website of the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center, a fusion center that covers the Silicon Valley area.

And they show that the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Homeland Security actively monitored TikTok for signs of unrest during the George Floyd protests.

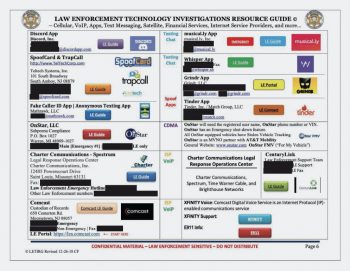

The number of requests for subscriber information that TikTok says it receives from law enforcement is significantly lower than what U.S. tech giants reportedly field, likely because police are more accustomed to using data from U.S. companies and apps in investigations. TikTok enumerates its requests from law enforcement in a biannual transparency report, the most recent of which says that for the last half of 2019, the company received 100 requests covering 107 accounts. It handed over information in 82 percent of cases. Facebook, by contrast, says it received a whopping 51,121 requests over the same period, and handed over at least some data in 88 percent of cases. A 2018 document found in BlueLeaks titled “Law Enforcement Technology Investigations Resource Guide” gives police details on how to obtain records from Musical.ly, which was acquired by ByteDance and merged into TikTok that year.

In the releases shown in BlueLeaks, TikTok handed over multiple IP addresses, information about the devices used to register for accounts, cellphone numbers, and unique IDs tied to platforms including Instagram, Facebook, or Google if the user logged in using a social media account. (Business Insider first reported the specifics of what TikTok collects.)

It is unclear whether these data releases were in response to warrants, subpoenas, or other requests, and the company would not give details, citing user privacy. All social media platforms are required by law to comply with valid court orders requesting user information, but what they actually provide can vary widely, said Ángel Díaz, an expert on national security and technology at the Brennan Center for Justice. Companies also have the right to challenge requests for user data in court–though they often don’t do so.

The accounts for which TikTok handed over data in the BlueLeaks dump range from influencers with tens of thousands of followers to people who primarily post for friends. One user contacted by The Intercept said they were unaware that their information had been given to law enforcement. Díaz said that in certain emergency situations, where moderators have a good-faith belief that there is a threat to someone’s life or a risk of serious physical harm, tech companies may voluntarily turn over information to the U.S. government without notifying the user. TikTok restored access to the account after The Intercept asked the company about it.

“We are committed to respecting the privacy and rights of our users when complying with law enforcement requests,” said TikTok spokesperson Jamie Favazza.

We carefully review valid law enforcement requests and require appropriate legal documents in order to produce information for a law enforcement request.

TikTok has tried to distance itself from its Chinese origins, hiring a former Disney executive as CEO, engaging lobbyists with ties to the Trump campaign, and pledging to add 10,000 positions in the United States. Some of that expansion is apparently coming in the area of cooperation with authorities. TikTok recently sought out a law enforcement response specialist and is currently recruiting a global law enforcement project manager. The team that reviews law enforcement requests is based in Los Angeles, Favazza said.

One satirical TikTok video even got a dedicated intelligence report.

The BlueLeaks documents also indicate that U.S. federal investigators and police–some of whom are themselves enthusiastic TikTok users— increasingly view the app as a useful tool. In the early days of the George Floyd protests, law enforcement used TikTok, along with Facebook, Twitter, and other social media apps, to track protests and dissent.

An FBI report from June 2 titled “Civil Unrest May 2020 Situation Report” alleged that TikTok was among the apps being used to promote violence. “Reporting nationally indicates individuals are using traditional social medial platforms and encrypted messaging applications (YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Telegram, Topbuzz.com, Snapchat, Wickr) to discuss potential acts of violence.” In lieu of actual examples of physical violence, the document pointed to the doxxing of officers, “rumors about false activities,” and, cryptically, “false reports of violence to incite violence.”

Three days later, another FBI dispatch warned,

An identified user posted a video on TikTok demonstrating which tab to pull to quickly remove body armor of LEO/military, saying ‘do with this information what you will.’ The post was gaining significant traction.

One satirical TikTok video even got a dedicated intelligence report, from DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis. On May 31, a 19-year-old TikTok user who goes by the handle weirdsappho posted a video riffing off a tweet that comedian Jaboukie Young-White, a correspondent for “The Daily Show,” wrote after the National Guard was deployed to Minneapolis.

Young-White tweeted, “thank god they’re bringing in the army,” at a moment when anxiety about the deployment was running high. “I would be heartbroken if someone disabled a tank by putting water balloons filled w sticky liquids (esp some sort of sugar/milk/syrup combo) into a glass jar and throwing it at the windshield, rendering it inoperable support our troops.” In her video, weirdsappho included some of the replies to the tweet, which expanded on the joke.

The DHS report reprised weirdsappho’s video, quoting the tweet and the replies verbatim, without explaining their source or giving context. The intelligence report bore the subject line “Social media video provides TTPs”–tactics, techniques, and procedures–“on how to interfere with the U.S. National Guard during riots,” suggesting that the teenager was an imminent threat. The existence of the dispatch was first reported by the online news site Mainer.

In last week’s executive order, Trump cited concerns that TikTok’s ownership by ByteDance could “allow the Chinese Communist Party access to Americans’ personal and proprietary information.” TikTok’s track record, and ByteDance’s obligations under Chinese law, do present unique security concerns. The Chinese state has invested significant resources in using artificial intelligence to monitor and manipulate public opinion, and ByteDance has been brought along in that effort. ByteDance recently established a joint venture with a Chinese state media group, leaving open the possibility that some of its technology might be used for propaganda purposes.

TikTok’s privacy policy states that the company may share user information with “a parent, subsidiary, or other affiliate of our corporate group.” Multiple class-action lawsuits have accused TikTok of sending data to China, though TikTok says that the data of U.S. users is stored in Virginia and backed up in Singapore. TikTok has also censored political speech that is disfavored by the Chinese government, including videos about the Hong Kong protests and about the internment in inhumane camps in northwestern China of Uyghurs, an oppressed Muslim minority group. Internal documents previously obtained by The Intercept show that TikTok instructed moderators to suppress posts created by users who were deemed poor, ugly, or disabled. The guides appeared to have been hastily translated from Chinese.

At a moment when we’re seeing attempts by the administration to draw a contrast in terms of values and ideology with China, these eerie parallels that keep recurring do really undermine that.

“The common concern, whether we’re talking about TikTok or Huawei, isn’t the intentions of that company necessarily but the framework within which it operates,” said Elsa Kania, an expert on Chinese technology at the Center for a New American Security. “You could criticize American companies for having an opaque relationship to the U.S. government, but there definitely is a different character to the ecosystem.” At the same time, she added, the Trump administration’s actions, including a handling of Portland protests that brought to mind the police crackdown in Hong Kong, have undercut official critiques of Chinese practices:

At a moment when we’re seeing attempts by the administration to draw a contrast in terms of values and ideology with China, these eerie parallels that keep recurring do really undermine that.

Last week’s executive order takes effect 45 days after its issuance. Trump appears to favor ByteDance selling TikTok to an American owner, with Microsoft being the frontrunner. If that happens, some concerns about data privacy with regards to China might be eliminated. But the BlueLeaks documents highlight that without more restrictions in the United States on what companies can collect and hand over to investigators, there’s reason to worry about any social media platform, American or Chinese.