Michael Mark Cohen is an Associate Teaching Professor of American Studies and African American Studies at UC Berkeley. Much of his published work to date has explored class conflict and radicalism in America from the 1880s to the 1920s. In his 2019 book, The Conspiracy of Capital: Law, Violence, and American Popular Radicalism in the Age of Monopoly, Cohen argues that the culture of popular radicalism for which this era is now known was brought forth by a coalition of union organizers, outspoken revolutionaries, and civil liberties lawyers, among others, who were tireless and unflinching in their criticism and defiance of the gilded age capitalism that sought to dominate the working class. Cartoonists were a crucial element within this vanguard, as they encapsulated radical ideas and ideals in succinct, accessible ways. On his website, cartooningcapitalism.com, Cohen offers a thorough and loving tribute to their work, as he provides an overview of the artists who shaped this era of cartooning and gives context to the media landscape in which they operated. In this interview, conducted by telephone in January 2021, then copyedited by email, Michael Mark Cohen and Ian Thomas discuss cartooningcapitalism.com, American Popular Radicalism, and the current state of radical cartooning.

Ian Thomas: Thank you for taking the time to talk to me. As an overview, can you give me some background on your scholarly work and your work as Associate Teaching Professor of American Studies and African American Studies at UC Berkeley?

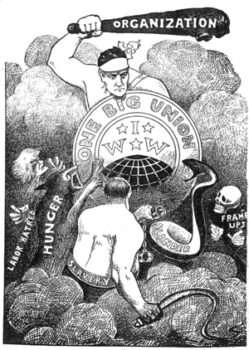

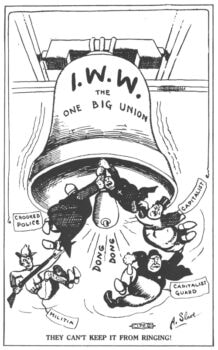

Michael Mark Cohen: I am an Associate Teaching Professor of American Studies and African American Studies at UC Berkeley where I teach courses on post-Civil War U.S. history and culture. I recently published a book called The Conspiracy of Capital: Law, Violence, and American Popular Radicalism in the Age of Monopoly and it looks at the history of radical social movements in the United States that attempted to overthrow capitalism between the Haymarket bombing of 1886 to the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti in 1927. The book considers the interplay between these social movements and the use of conspiracy laws to criminalize the political activism of the working classes while enabling the capitalist state to wield a wide range of violent countersubversive tactics to retain and expand its power. This era witnessed the emergence of a wide range of anti-capitalist social movements, including labor and union movements, the birth of the Socialist Party in 1901, the anarchist internationals founded in the 1880s, as well as the Industrial Workers of the World (known as the IWW or the Wobblies) founded in Chicago in 1905, all the way up to the birth of the Communist Party of the United States as an underground party in the aftermath of World War I.

I spent a tremendous amount of time digging around in old socialist and union newspapers, journals, magazines and pamphlets where I expected to read the work of earnest revolutionaries discussing socialist strategy and news from the latest strikes around the world. Of course, I found all that and more. But what most surprised me about this popular literature was that it also served as a platform for so much great cartooning. Some of these cartoons were drawn by what are today very well-known American artists, including several of those responsible for creating an American high modernism in the early 20th century like Stuart Davis, John Sloan, and Maurice Becker. But these pages also included literally hundreds of cartoons drawn by anonymous readers, some of whom signed their cartoons as “Fellow Worker.” The IWW papers like Solidarity or the Industrial Worker specialized in this type, publishing brilliant cartoons every week drawn by unknown union members who sometimes signed their cartoons with just their membership numbers and were never heard from again.

Taken together, these cartoons were an enormously effective tool for spreading radical politics in terms that everyone could grasp. Together these cartoons helped draw together immigrant workers, non-English speakers or the semi-literate alongside more sophisticated, urban radicals into a common message and a common cause. And they did so much more effectively than any other communicative medium I found. Not only was this great art being produced by workers and artist from outside the high art world, but it was outstanding propaganda for a growing movement.

Along with union organizers and civil liberties lawyers, you cite the work of “rabble-rousing cartoonists,” to quote the description in the book, as among those responsible for this culture of political radicalism. What informed that assessment? Was it essentially the accessibility of these cartoons and the sheer volume of them?

Pretty much every radical magazine, except for a few of the most austere ones, had imagery and cartoons. And several magazines specialized in cartoon art. What I found across this archive was a movement through which American radicals collectively built a revolutionary popular culture. Today, one can think about Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns, the impressive growth of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) or the countless Gen Z Communists meme accounts on Instagram as a certain measure of popularity. But these recent movements both lack the organization structure and have a much smaller base relative to, say, Samuel Gompers leadership over the American Federation of Labor or what Eugene V Debs’ Socialist Party was able to command in the early 20th century.

One way we can think about the success of this popular radicalism was its ability to cross regional and ethnic lines to build a genuinely national movement. Midwestern revolutionary socialism founded the Appeal to Reason, a weekly socialist newspaper edited and printed in the small town of Gerard, Kansas. The Appeal helped to make much of the rural Midwest, especially Oklahoma and Kansas, into the active heart of the Socialist Party in the early 20th century. The Appeal was absolutely massive, selling more than 750,000 copies a week at its peak in the 1910s, making it one of the widest circulating leftwing papers in U.S. history. Or you get The Masses, created in 1913 in Greenwich Village in New York City, as the center of a multi-racial, feminist, high-modernist magazine that, at the same time, not only employed the most important radical journalist of their generation, especially Max Eastman and John Reed, but also hired Art Young to be their cartoon editor.

For his part, Art Young was originally from rural Wisconsin. He worked under Thomas Nast—the king of American political cartooning—at a newspaper in Chicago. In the 20th century, Art Young went on to become the most beloved radical cartoonist in American history, publishing cartoons in The Masses, The Liberator and across the Left spectrum of outlets, but also in liberal magazines like Life, The Nation, Metropolitan and others. As a socialist cartoonist reaching into the mainstream, Art Young was unique, his success was enabled by a simple and easily recognized style. The Comics Journal has published several good pieces on Art Young over the years and there are two new Fantagraphics books, pushed by major collectors, that have reprinted some of Art Young’s less overly political work.

Can you describe for me the media landscape in the era you are describing? Was it the appetite for this content that allowed for it to be so prevalent? Importantly, I think, you place it in contrast to today’s landscape, which is a much more centrist or even conservative media landscape and the outlets that represent the kind of perspective espoused in these cartoons are much fewer and further between. What allowed for this era of American popular radicalism to be what it was and have the reach that it did?

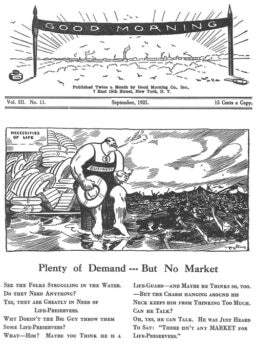

It’s a good question, but I don’t think it’s a question that can be answered purely on a media level. Part of what is actually happening in this era is the rapid industrialization of the United States. On an economic level, it’s the ongoing destruction of handiwork and craft labor and its gradual replacement by deskilled workers laboring on ever larger assembly lines. Men who were born into generations of skilled laborers, craftsmen who owned their own tools and thus commanded a sense of independence born of skills handed down from their fathers and their fathers and their fathers, suddenly found themselves immiserated, ground down to the status of “wage slaves” as capital’s deployment of machinery in the labor process undermined the freedom and financial well-being of American workers. Literally millions of Americans who once led dignified, self-sufficient lives now became proletarianized, dispossessed of their skills and sold on the labor market as “free” wage workers who barely outran poverty.

As industrial capitalism spread across the United States after the Civil War, inequality dramatically widened in its wake. To the independent farmers, railroad and steel workers, the newly emancipated Black freedmen and women of the South, as well as the large number of Irish, Italian and Jewish immigrants who arrived in this country after being promised streets paved with gold and a ladder of success, all this promised opportunity proved to be an illusion. The American Dream, as it was and as it remains, turned out to be mostly bullshit, or put more accurately, it was capitalist anti-union propaganda.

So at the end of the 19th century, there broke out tremendous disruptions in the political economy. Workers felt a real desire to resist this Monopoly-driven, Wall Street-based ruling class comprised of rich, awful, Social Darwinist tycoons like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan and other so-called “Robber Barons.” It was the greed and corruption of this class that repeatedly sent the country into chaotic financial crises caused by stock market manipulation. In 1873, for example, a failed attempt to corner the gold market led to a financial panic, followed by mass unemployment that lasted nearly a decade. In 1893, another Wall Street crash destroyed the national economy in what many came to recognize as a characteristic feature of boom and bust cycles intrinsic to capitalism.

So there takes root in the public a revolutionary desire among millions, native born and immigrant, Black and white, Northern, Southern and Western to imagine a world beyond the greed, poverty and disaster fueled by capitalism. To organize that growing despair, to narrate that sense of crisis, to educate the public about what was at stake in the accumulation of capital, a radical press emerged in the late 19th century to both draw people into the movement and to strengthen the movement’s intellectual organization.

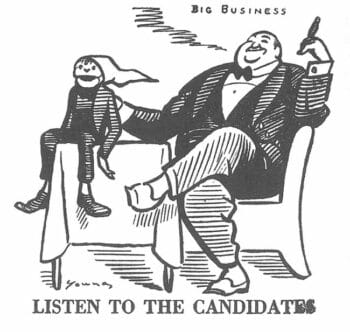

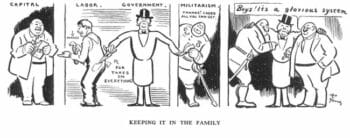

I don’t want to say that this revolutionary movement thrived because of cartoons. That’s too reductive. [Laughs] No cartoon is that powerful. Material economic conditions in the United States are what’s growing this revolt. But the cartoons have a way of both feeding and articulating this expanding sense of crisis, of expressing this anger and outrage, and translating the specific experience of a worker in Pittsburgh, or a farmer in Kansas, both of whose future is being encl These cartoonists could illustrate the widening class struggle—because that’s what this was, and still is—and turn it into dramatic personifications of global economic forces, both connecting and personalizing economic struggles that otherwise may seem entirely abstract. In these cartoons, the abstract power of capital becomes the character of the capitalist. This grotesquely fat, suit-wearing white man—always a white man— becomes a character through which radical cartoonists could simultaneously mock and analyze the social structure they sought to overthrow.

Now, you asked about the media landscape in the U.S. at the time, and in the late 19th and early 20th century, newspapers and political cartooning were big business. Hearst and Pulitzer were the two major newspaper publishing chains and they had massive circulations driven in part by popular cartoonists. Half of that was the diversionary comic strip silliness that you’d expect to find at the back of the paper (which I unapologetically love), while on the editorial pages there were the political cartoonists (which I take all too seriously). Political cartooning, particularly in an era before it becomes technologically viable to reproduce photographs, was critical to the newspaper business. Several cartoonists, like Thomas Nast, had large national followings. But these papers—Hearst, Pulitzer and others—were highly partisan. Nast, for example, was a committed Republican. Indeed, there was little value placed on the concept of journalistic objectivity. Then, as now, so-called journalistic objectivity was a bourgeois fantasy, an illusion pushed by media professionals of the middle of the 20th century. Instead, not unlike today, most newspapers in the late 19th and early 20th century promoted one political party over another. As in this one is a Democratic paper, while that one is a Republican paper. Or it might be a Populist paper or a Socialist paper or a union paper. And as a result there were hundreds of daily newspapers across the country, often with dozens of competing editions covering the news in the big cities.

So, if I can pivot based on something you just said, I think the Liberal segment of the political spectrum tends to greatly value—I would argue that they overvalue—this notion of objectivity. You just said that such objectivity was not really the case in the late 19th and early 20th century. I would argue that it is demonstrably true that journalistic objectivity is a myth today, as well. Why do you think that value is so pervasive?

It’s a very good question. Let me point out a few things that don’t have anything to do with cartooning. One, capitalism leads to concentration, and the big papers–the New York Time, the Chicago Tribune, the SF Chronicle–knew that you could sell a lot more papers if you made a show of representing the news from the non-partisan political center, while still having opinion columns that appeals to both Republicans and Democrats in turn. That has the effect of widening your audience of readers, because you’re not alienating Republicans by being some fervently Democratic paper and so on. But as it widens the audience, newspapers also narrow the political spectrum. It keeps the range of political viewpoints within a tightly controlled, respectable bounds. So, if you’ve looking at the opinion pages of the New York Times today and you have a “Leftist” columnist like Paul Krugman, who’s like not a leftist at all—he’s a Liberal, at least he calls himself a Liberal. But it’s not like there’s an Anarchist on the payroll, or someone who spends their weekends fighting and doxing fascists who gets to write a weekly column for the New York Times. (Although, of course, these papers do on occasion print columns by fascists). These centrist papers set the a boundary for what is and is not “fit to print.” What you get in U.S. media, particularly after the defeat of Nazism and the victory of Communism in World War II, is a commitment to a belief in journalistic objectivity as a form of Liberal-Centrism. This really takes hold in the Cold War era in which mainstream political science was focused on questions of forging a liberal consensus and political pluralism which accepts industrial capitalism as the price of rejecting both the extremes of the left and right.

So you get a new political alignment that seeks to mitigate or contain what comes to be called “extremism” as the basis for the practice of journalistic run by experts and governed by a faith in objectivity. We find this first and most effectively in the work of Walter Lippmann and his book from the 1920s called simply Public Opinion. When we look around the media world today, with social media and hyper-partisan TV networks like Fox and OAN, we can see how this model is outdated despite the persistent ideological influence and large market position of prestige outlets like the New York Times and CNN who still claim to uphold those illusory standards.

That sounds like a much larger, longer conversation than we have time for. To get back to the work in your book and your website, cartooningcapitalism.com, you provide an overview to some of the cartoons from the era about which we are speaking. Can you speak to what your goals were in putting these cartoons back into the world and giving them some context?

Well, to be blunt, I built the website because I couldn’t find anyone that would publish a book of these cartoons. Fantagraphics, who publishes The Comics Journal, wouldn’t give me the time of day. [Laughs] At the time, no one was saying to me ‘Oh, yes, socialism and century old cartoons… so cool! Let’s publish a book of forgotten lefty drawings!’ It didn’t matter that they are all in the public domain and carry no copyrights. But I had all these cartoons collected. I researched their creators. And I cleaned them all up. They looked really good to me and I went out to find someone who would publish these and got nowhere. Publishers either saw them as too obscure or too political, especially for the comics fanbase, who, politically speaking, is a very mixed bag. Comics fans are a very diverse and eclectic crowd and I am one of them. I certainly have no intention of insulting comic book readers or publishers, but, for some of the reasons I was talking about above, the comic publishing industry was not as into this stuff as I was. So I built a website and gave it all away for free.

After the Occupy movement in 2011, I finally started to see these cartoons coming back. All of a sudden, there were new, widespread discussions about socialism and anarchism and class politics and what a new Socialist Party might look like? There seemed to be a really deep desire to articulate a new leftist politics for the 99% as the new slogan went. The history of left organizations found a renewed life among Millennials and those of us who were dissatisfied with the lack of real political change in the Obama era.

Terms like plutocracy and oligarchy were back in circulation. We appeared to have come full circle, and the late 19th and early 20th century era of deregulated, predatory monopoly capitalism was back with the neoliberalism and financial collapse of our own time. Born in the Reagan era, neoliberalism restored the 19th century’s yawning, expanding inequality after decades in which full-employment, union membership, civil rights for Black folks, new opportunities for women, and a robust middle class was America’s primary social and economic goal. Neoliberalism restored the era of Wall Street domination in which the market became the oracle of public policy and the rich got richer while the poor got poorer. As a historian, I find that the past is a resource for the future. And I find it inherently compelling to argue that ‘we’ve been here before. Some version of this crisis is familiar. We have seen this level of inequality. We have seen what happens when Wall Street takes over the policy-making and political apparatus of the country. And we know that results are not good. A century ago this was also happening, and look, these activists and artists knew how to fight back.’

I felt was that there really was a need for socialist theory and there was a need for people to understand the dynamics of commodity production, the extraction of surplus value, the enclosure of the commons, and the proletarianization of entire generations; all of the things that you can understand if you have the time and motivation to read all of Marx’s Capital. Or, just maybe, you can be introduced to these ideas by picking up these cartoons. So many of these cartoons are exquisite translations or popularizations of sophisticated social theory, dramatizing complex political and economic concepts in an entertaining fashion. And so I felt an urgency that the publishing industry did not share, and I said ‘Fuck it, I’ll buy me a domain name and build a website.’

The title of the website, Cartooning Capitalism, comes from Eugene Victor Debs, the four-time candidate of the Socialist Party for president of the United States, the child of Terre Haute, Indiana, who in the 1920 election, received more than 1 million votes while serving a federal prison sentence in an Atlanta Penitentiary for making an anti-war speech. In an introduction to a collection of radical cartoons, Debs wrote: “Cartooning capitalism is far more inspiring than capitalistic cartooning.”

Can you tell me what the process was like of tracking these cartoons down and collecting them and cleaning them up? I mean was it difficult to track these down? Was it difficult to establish the chronology of when they were published and to put them into context? What resources were you using?

I started this research as part of my doctoral dissertation in American Studies at Yale University where I had access to abundant library and archival resources. Later, I also got my first academic job at Duke University, where they hold the papers of the U.S. Socialist Party for reasons that I never really fully came to understand. All of which is to say that as an academic historian, I have learned a set of research skills. I am dedicated to reading, researching, writing and collecting original source material so as to distill their significance into historical and cultural arguments.

I was researching the history of conspiracy laws in the United States and the ways in which conspiracy laws are used to destroy plebian social movements, particularly labor unions and other radical organizations like the Communist Party. There’s a long history of the explicitly politicized use of conspiracy laws to defend monopoly capital (defined by the Sherman Act of 1890 as a “conspiracy in restraint of free trade”) against organized popular resistance. The conspiracy laws criminalize collective action in all sorts of ways, including in this era, banning strikes, picket lines and boycotts. I still find this question quite fascinating (even now as the Justice Department considers conspiracy and sedition charges against those who stormed the capital on 1/6/2021). While I was digging into conspiracy theories in this era, I first discovered and then gradually became enraptured by these cartoons. So I just started printing them out as I went cross-eyed reading microfilm as a way of keeping myself engaged. Once I had a large enough stack of these images, I bought myself a clunky early 1990s scanner and I started digitizing the cartoons into Photoshop where I learned to clean them up, pixel by pixel.

At the time, there were some reprint collections available, but far, far more of these cartoons could only found in their original sources, available only on microfilm, in bound editions in libraries, or in special collections archives. Today, there is much greater access to these sources, including some great reprints and digital archives, such as the huge international cartoon collections at Marxists.org. The advantage for me, working originally in analog, was that these cartoons were mostly just black line drawings, so I could photocopy them and they’d look pretty good. This form, the simple black and white line drawing, is also why these cartoons were able to circulate as widely as they did in radical periodicals. These shoestring left-wing publishing outlets could reprint them cheaply.

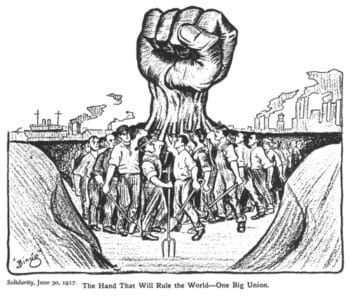

Some Art Young cartoons would get published and republished six or seven times across the left press because they were that popular. Art did want, or rather need to be paid for his work, and he earned his money selling cartoons to the liberal press. But he was also a committed member of the Socialist party who ran for public office in New York City and faced not one, but two federal sedition trials carrying a 20 year prison sentence for the crime of drawing subversive cartoons. Throughout this era, radical cartoonists were censored by the post office and attacked by the federal government for what they drew. Ralph Chaplin, one of the leaders of the IWW, was convicted and sentenced by a federal judge to 20 years in prison for his work as editor of the Wobbly newspaper Solidarity. This is a man who wrote the labor anthem “Solidarity Forever,” organized strikes and unionization drives, all while drawing hundreds of a great cartoon. Chaplin was simply a creative genius of the American revolutionary working class. And for this crime, the U.S. government tried to kill him.

You mentioned earlier how succinctly you felt these cartoonists summed up complex political and social theory, such as Marx’s Capital. Were these artists cartoonists by trade? What were the backgrounds and trajectories of Art Young and Ralph Chaplin, for example.

Art Young wanted nothing more in life than to be a cartoonist. Very few of us live that elementary school dream of what we want to be when we grow up, but damn it Art Young did. [Laughs] He was something of child prodigy as an artist growing up in a small Midwestern town where he started publishing cartoons in his local newspaper at a very young age. He moved to the big city and got a scholarship to receive some formal arts education in Paris, but he became very sick while abroad and had to come back to the United States. At that point, he decided that fine art was not for him, and that he would become a professional cartoonist. The artist that Art Young admired most of all was Gustave Dore, whose engravings illustrating Dante’s Inferno became Young’s most profound influence. Over the years, Art produced three different parodies of this work, writing and drawing three books on a cartoonist’s descent into the modern Inferno. The last of these, 1934’s Art Young’s Inferno may be Young’s single greatest work.

Anyways, Young came to socialism sort of late in life, well after the Haymarket bombing of 1886 in Chicago in a conspiracy of anarchists were accused of throwing a bomb that murdered several police officers. In fact, Young was sent by his editor to draw portraits of the seven men in the Cook County prison several days before one of them committed suicide and four others were executed for the crime of conspiracy and for being anarchists. (No one knows for sure who threw the bomb). When the new Governor of Illinois exonerated the three remaining anarchists in 1893, attacking the prosecutor for malicious persecution of innocent men found guilty by association, Art Young realized that he had played a part of that witch hunt. This personal crisis started him on a path of self-reflection and redemption in which he publicly converted to socialism. He had always been something of a sentimental liberal, caring deeply as he did about the suffering of the poor, but then he goes searching for not just a socialist education, but socialist outlets where he can publish new types of cartoons. By the 1930s, Art Young successfully maintained his radical sensibility while keeping clear of the sectarian conflicts between unionists, Socialists and Communists, largely giving off a grandfatherly vibe to younger radicals who respected his long memory and body of work linking the Haymarket tragedy to the new radicalism of the Great Depression.

Ralph Chaplin, on the other hand, was a much more dangerous figure. [Laughs] In his autobiography, he describes himself as a working-class tough growing up who found his way, through work, commitment and intelligence into leadership positions in a number of labor unions, the IWW most importantly of all. He was a working-class militant who had real skills in organizing, drawing, songwriting, and investigative journalism. The man was a quadruple radical threat who saw his songwriting and cartooning not as an artistic end in itself, but as being in service of revolution. Chaplin eventually became the editor of the IWW’s main magazine, Solidarity, and right-hand man to William D. “Big Bill” Haywood, the secretary-general of the IWW and one of the most charismatic figures in the history of the American Left. Chaplin becomes one of the IWW’s culture warriors, drawing in people like Joe Hill, the Wobbly songwriter who also was a cartoonist.

Joe Hill, a Swedish immigrant and itinerant worker, wrote magnificent labor songs and drew great cartoons that perfectly expressed the IWW’s distinctive ethic and culture. That was until Hill was arrested in Utah for a murder he did not commit, where he was executed by firing squad in 1915 after uttering his famous last words: “Don’t mourn, organize!” Chaplin offered the eulogy at a mass funeral when Hill’s body returned to Chicago.

Art Young was an artist who believed that socialism was the hope of humanity and he used his art in service of that hope. Whereas, Ralph Chaplin was a committed revolutionary who took up the cartoonist’s form as a mode of propaganda towards freeing humankind from the burden of capitalist exploitation. Joe Hill perfectly blended the two positions, which is part of the reason why the ruling class in the Rocky Mountains framed and executed him. These stories are important just in case anyone is tempted to think that cartooning doesn’t matter, or that it’s a safe way to make a living.

I find that in talking about the Left, either historically or in contemporary terms, I think there is a tendency to turn it into a monolith and I think it’s important to try to get at the nuances within the spectrum of the Left. You mention Art Young as someone who was able to move into the mainstream cultural discourse. Can you talk about how his work was received there? After this cultural moment passed, where did these cartoonists go? What happened to them?

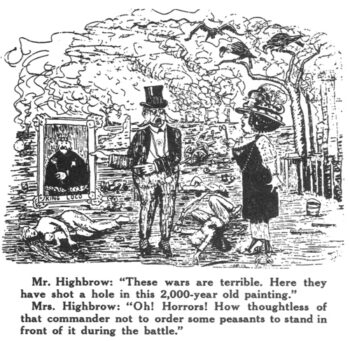

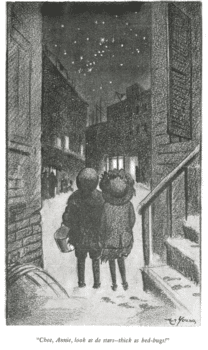

There are a couple of different figures to think about in this regard. Including Art Young, Robert Minor and Maurice Becker. By the 1920s, Art Young did draw the sort of Democrat versus Republican cartoons that satirized the dueling political parties from a broadly socialist point of view. He could take a “pox on both houses” approach, condemning both sides for being corrupt and venal. Art Young also had a deep and genuine sentimental strain. There’s a famous cartoon that he did of two children holding hands at night, walking out of an alleyway in a slum, probably somewhere in the Bowery in New York and as they look up into the sky the boy says: ‘Chee, Annie, look at de stars–thick as bed-bugs.’ It’s a sentimental cartoon of the Progressive era which a liberal could read and swoon over, crying over the poor children rather than demanding an end to child labor and the destruction of capitalist landlordism. While the humanity and naïve suffering of these children is not in question, the openness of the message in this cartoon gave Art’s work crossover appeal between the left and the mainstream

Of course, we could talk all day about the differences between various factions of the American left in this era, as today. There were hardcore revolutionaries like Jack London, John Reed and Emma Goldman. And there were elected “bridge and sewer socialist” like Milwaukee Congressman Victor Berger who really just wanted good, honest government that could provide for the people as a part of the left flank of the Progressive movement in the early 20th century.

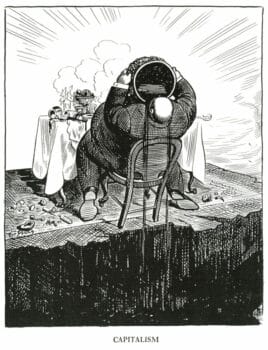

But there’s also the fact that Art Young was constantly dueling with conservative editors who messed with his work. Art Young’s single greatest cartoon, which is also, to my mind—full hyperbole mode here—the single greatest political cartoon ever created, which is the central image of my website. It’s simply captioned ‘Capitalism” and it features a fat man seen from the back who sits before a banquet table piled high with food and dirty dishes, tipping backwards in his chair over a black abyss while pouring still more food down his insatiable gullet. Drawn around 1920, one would be hard pressed to find a more contemporary image of capitalism that this century old image. This is the environmental abyss, the COVID abyss, the abyss of poverty. So when it comes to capitalist crises, you name it, it becomes legible in this image. I don’t know for a fact that Art Young read Karl Marx’s Capital (though I sort of doubt that he did). But there is a passage in Capital in which Marx talks about the motto of the capitalist being “apres moi le deluge,” or after me the flood. I’m here to get mine, says the capitalist, and once I’ve got it, fuck everybody else. I’m rich, let the waters rise. This of course remains the ethical standard of the capitalist class today. The problem was that when Young tried to publish this cartoon in Life Magazine, they recaptioned it simply as “Greed.” Art Young was livid with his editor and pulled the image, later publishing it in his own magazine as it was intended. It is important to understand the distinctions between an image like this labeled ‘Greed’ and the same image labeled ‘Capitalism.’ Part of the what’s at stake in this is taken again from Marx’s great work. Unlike Adam Smith, Marx’s critique of capital is not a moral one, it is a logical and historical critique. Marx is not arguing that the capitalist class is immoral, or that these are bad people who could run this system in line with different ethical guidelines beyond greed if they chose. Marx’s point, illustrated by Young’s caption, is that it is the system of capitalist production–not the ethics of the ruling class—that exploits the proletariat and claims all the pleasures of life in an endless spiral of accumulation before the inevitable bust of economic crisis. The capitalist is as much a part of this system as are the workers, and the whole grotesque system will, sooner than we think, topple over into that very abyss below his feet. This crash will come not because of the greed or the moral turpitude of the capitalist class, but because of the nature of an economic system dedicated to producing profits for the few over the production of necessary goods for the many. Art Young understood what was at stake in labeling this cartoon ‘Greed,’ because that was something good liberals could rally against and say, performatively wringing their hands, ‘Oh, greed is bad.” All while supporting and profiting from the expansion of capitalism itself. It is the system that is in crisis, not the values of lords who sit precariously atop it. And to confuse the two is the difference between revolution and reform, between the possibility of transformative action and a simple emotional response among the comfortable middle classes.

Art Young ran into all kinds of problems with this liberal press who didn’t understand his work and sought to de-fang it in ways both subtle and rather crude. It was an ongoing process of negotiation for him to win a space of artistic freedom from within the realm of necessity. This is, I think, something that every artist understands; this dialectic between your own artistic impulses, your own political beliefs, and the needs of your publisher, the needs of your gallerist, and the desires of your audience. Outright censorship was also something that Art Young dealt with his entire life. He was sued by the Associated Press once and later had his magazines banned from the U.S. mail. Any radical artist of any stripe is going to deal with censorship from time to time. But the compromised stuff that did appear in Life magazine, that work was deeply, deeply beloved by huge audiences and it ensured his survival as a working artist.

Now, what happened to the rest of this generation of radical artists? The wave of revolutionary agitation that started in 1886 reached a crescendo around World War I when most of these radical social movements—the Socialist Party, the IWW, anarchists, and the miners and steel unions—were all violently crushed by a combination of vigilantism, corporate violence (strike breakers and private detectives), and state power in the Red Scare of 1919. During the war, the federal government built an enormous repressive apparatus in the form of the FBI, immigration and deportation courts, and the Justice Department to target those who stood against U.S. involvement in the war. Of all the Socialist parties in the world at the time, only two parties rejected their nations’ entry into World War I: The U.S. Socialist Party and the Russian Socialist Party. The former was crushed in the Red Scare, while the latter seized power in Russia and formed the Soviet Union under the Bolsheviks.

During the 1916 elections, there was tremendous opposition to entry into the Great War by a majority of the American people. Of course, the capitalist class was very motivated to enter the war as a way of making money by selling steel, guns and handing out loans to Brittian and France And so, once the U.S. moved to join the war in 1917, the opponents of American capitalism—the unions, socialists and others—had to be crushed. This began with the mass arrests and subsequent federal trials of hundreds of leaders of the IWW. Put on trial in Chicago, the jury convicted the IWW members—including Big Bill and Ralph Chaplin—of more than 25,000 felonies after less than five hours of deliberation at the conclusion of the longest federal trial in U.S. history to that point. Haywood fled to newly Communist Moscow and Chaplin served several years at Leavenworth. The government had effectively broken the organization.

Also, at this time, the state empowered several far-right vigilante organizations, particularly the American Legion to attack labor unions. There are far too many incidents where members of the IWW like Frank Little or Wesley Everest were assaulted, shot and lynched as part of suppressing strikes in key industries like copper and timber. This wave of violence poured over the country, accompanied by censorship and mail bans that destroyed the radical press. The results were found in the reactionary politics of the 1920s, shaped on a national level by white supremacy, eugenicists restricitons on immigration, and Jim Crow segregation in the South. It was an era in which the second Ku Klux Klan dominated politics in the states where socialism once bloomed across much of the American Midwest and West.

So, a lot of radical cartoonists went underground or fled the country. Maurice Becker, one of the cartoonists I wrote about in some detail, got out of jail early on a technicality and fled directly to Mexico where he met Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siquerios and others Mexican artist who also were Communists. When he returns to the U.S., Becker too joins the Communist party.

Or we might take the trajectory of Robert Minor, a very popular cartoonist who was one of the Hearst paper’s most famous and highly paid artists at the end of the 19th century. Despite this capitalist success, Minor was drawn to the radical left and quit the Hearst chain, becoming a socialist, drawing several images for The Masses and then going on to join the Communist Party. Despite his success as an artist, Minor eventually gave up cartooning entirely to become a leading figure in the party, eventually taking over leadership for the defense campaign of two Italian-American anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, who were tried and executed for a crime they did not commit in Massachusetts in 1927. So here is one artist who gave up the money, fame and eventually their artistic talent for the cause of revolution.

You described the current media landscape in which these these viewpoints are taken up as niche, especially in comparison to what it was in the era covered in your book. Do you see parallels, though? Do you see cartoonists taking up this work and doing things that might match it, if not in craft then maybe in spirit? What are the parallels you see between that era and this era?

Circumstances are very different now, capitalism is both more unstable and far more widespread than it was a century ago. Things are a lot blurrier in some ways, but in others, like the ecological crisis, they are much clearer. The United States has returned to 19th century levels of economic and political inequality. We don’t have Jim Crow segregation anymore, but we have the mass incarceration and police murders of Black people. So on the level of racist violence and deregulated capitalism, there are tremendous parallels between the late 19th and early 20th centuries and now.

And yes, there are most definitely cartoonists that are keeping this radical tradition alive. In the 1970s one thinks about the breakthrough series of books starting with Rius’ still unequaled Marx for Beginners. Or, one of my favorites, Anarchy Comics which ran irregularly from the 1970s to the 80s. In the 21st century, several examples come to mind, beginning with the circle of artists around World War 3. I truly love and admire the work of artists like Sue Coe, Seth Tobocman, Eric Drooker, Peter Kuper, and Eli Valley. Working with these artists and others, the historian Paul Buhle has edited a range of wonderful books about radical politics including graphic histories of the Wobblies, and a series of radical biographies of Emma Goldman drawn by Sharon Rudhal, Rosa Luxemburg drawn by Kate Evans, Che Guevara drawn by Spain Rodriguez and Eugene V Debs drawn by Noah Van Sciver. Kyle Baker’s exceptional book about Nat Turner is a real landmark in this terrain . As is Joe Sacco’s entire body of work, especially his transformative work of cartoon journalism, Palestine.

But the one artist I really want to single out is Molly Crabapple, who I think is one of the great cartoonist of our moment—even if she may not really be a cartoonist. Molly is a New Yorker who works in every conceivable visual medium—painting, illustration, animation, cartooning and she writes brilliant books about social movements in at least four languages. As an artists, she crosses all of those boundaries and borders, but is also deeply committed to and works within the social movements for environmental justice, racial justice and labor. She was central artistic figure for Occupy Wall Street and the presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders. Recently she has done several stunning animations supporting the Green New Deal with Naomi Klein and AOC. She’s always using her artistic skills to serve the uplift of human freedom and liberation and the struggle against capitalism and racism. So, I think there are a lot of people today that keep this work of radial cartooning alive, but I have to say, maybe just on a personal level, that Molly Crabapple is my favorite. I think her stuff is just extraordinary and I believe (hope, imagine) that, were she to stumble across my webpage, she would find a world of old cartoons that could inspire her, and stand behind her contemporary vision and innovations.

There are lots of really outstanding cartoonists now. But it’s a very different, decentralized political landscape now, and there isn’t a single locus of radical energy like the IWW or the Socialist Party from a century ago. And yet, what is fascinating is the capability of the American left to coalesce rapidly around an immediate moment or cause. We’ve seen that with Occupy. We’ve seen that with Black Lives Matter. We saw it this past summer of 2020 where my city of Oakland, California filled up with extraordinary murals after downtown buildings boarded up in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. We’ve seen artists go to work for Bernie Sanders. We see them promote the agenda of AOC and Ilhan Omar, and the Green New Deal. I do think that things are harder for the left now than they may have been a century ago, in the sense that any alternative to hegemonic capitalism seems rather distant at times. And yet, I want to leave you with my firm belief that we are right now in the midst of a substantive leftist revival in the United States, particularly a revival of socialism in the United States. We can debate what kind of socialism that is and whether it is good or bad, but it’s undeniable that this is growing in size and sophistication and that artists will have a critical role in whatever movements we build going forward. Again, what Debs wrote more than a century ago remains true today:

The true art of the untrammeled cartoonist is now being developed, and [they] will be one of the most inspiring factors in the propaganda of the revolution.