Today, Frantz Fanon is frequently evoked in movement politics, but he is often misunderstood to be a Manichean thinker. To reach beyond this image and to return to Fanon, to his life and work, is to appreciate how original he was as a thinker.

Fanon’s theorisation began from lived experience. There was always an open-endedness to his politics. Self-determination had to invent the world rather than conform to a pre-existing script. If the door had been slammed shut by racist, colonial, European claims to monopolise universality, it would be re-opened by the concrete universal of the anticolonial struggle.

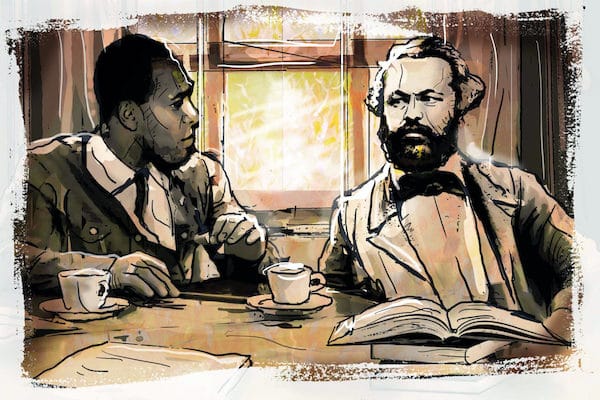

In The Wretched of the Earth (1961), Fanon’s critical engagement with Karl Marx is developed from within Algeria’s revolutionary anticolonial movement. But his most important quote from Marx is in Black Skin, White Masks (1952). The quote, which begins the concluding chapter, “By Way of Conclusion”, is taken from Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon:

The social revolution cannot draw its poetry from the past, but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped itself of all its superstitions concerning the past. Earlier revolutions relied on memories out of world history in order to drug themselves against their own content. In order to find their own content, the revolutions of the nineteenth century have to let the dead bury the dead. Before, the expression exceeded the content; now the content exceeds the expression.

Written in 1852, it was Marx’s poetic and dramatic historical account of the 1851 coup by Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, with its focus on how people make history but not under conditions of their own choosing, that incited Fanon’s attention. This existential and materialist view became essential for Fanon.

In the quote Fanon takes from The Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx is not only writing about the difference between the revolutions of the 18th and the 19th centuries, but also the difference between bourgeois and proletarian revolutions. Two paragraphs later, Marx argues:

Bourgeois revolutions … storm more swiftly from success to success … but they are short-lived … On the other hand, proletarian revolutions … constantly criticise themselves, constantly interrupt themselves in their own course, return to the apparently accomplished, in order to begin anew … until a situation is created which makes all turning back impossible.

Radical mutations

Likewise, Fanon insists the African revolution is “a historical process”, which, he writes in The Wretched of the Earth, “cannot be understood, it cannot become intelligible nor clear to itself except in the exact measure that we can discern the movements which give it historical form and content”. In its movement of new social forces, the form and novelty of the anticolonial revolution was previously “outside of history”.

Fanon’s reference to the revolution’s “form and content”, and his insistence that the creation of new subjectivities are not the result of “supernatural powers” but born in the revolutionary process, are reminiscent of the lines from Marx to which he refers. Marx writes that the revolution “cannot begin with itself before it has stripped itself of all superstitions concerning the past”; it must find its “own content” rather than “drug [itself] against [its] own content”.

It was the content “exceeding the form”, as Marx put it, that Fanon rediscovered in what he called the “radical mutations”–the ways in which people change in struggle–engendered by the revolution. He insisted that overcoming colonial oppression requires “a subjective attitude” contrary to “reality”, through which the oppressed become conscious producers of their history, transforming their circumstances and selves. Marx affirms this same spirit in his most famous thesis on contemporary German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.

In his 1960 notebooks, written while on a mission to consider the possibility of opening up a new theatre of the Algerian war from the West, Fanon observed: “We must once again come back to the Marxist formula. The triumphant middle classes are the most impetuous, the most enterprising, the most annexationist in the world.” In The Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx also wrote of a triumphalism expressed in how the bourgeoisie “conceal from themselves the bourgeois-limited content of their struggles”. They claim to represent the “universal will”, but in reality represent a faction.

Fanon adds that it was absolutely for their own will that “the French bourgeoisie put Europe to fire and sword”. The bourgeois revolutions drugged themselves with the poetry of the past, and Fanon warns that the African revolutions could do the same thing. The greatest challenge they faced, Fanon argued, was not simply material but political: “For my part”, he says, “the deeper I enter into the cultures and the political circles, the surer I am that the great danger that threatens Africa is the absence of ideology.”

There are echoes here, and in The Wretched, of Marx’s contention in The Eighteenth Brumaire that the “tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living … anxiously conjur[ing] up the spirits of the past to their service, … in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language”. Fanon opens the third chapter of The Wretched, “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness”, with his thoughts on this borrowed language.

He asserts: “History teaches us clearly that the battle against colonialism does not run straight away along the lines of nationalism.” For Fanon, the greatest challenge to the success of this battle is “the unpreparedness of the elite, the lack of practical ties between them and the masses, their apathy and, yes, their cowardice at the crucial moment in the struggle”.

Struggle within struggle

That this elite misrepresents its factional interests as the interests of the national as a whole is at the heart of what is problematic about anticolonialism for Fanon. In The Wretched, he becomes very critical of the talk of “Africanisation” as veil for bourgeois interests.

For Fanon, there is always an ideological struggle within the anticolonial struggle. His notion of intellectualising popular praxis expresses a new moment for freedom, developing new concepts grounded in the affirmation of the reason for popular revolt. It echoes other leaders of radical movements of the time, such as Hocine Aït Ahmed, one of the original leaders of the Algerian liberation movement, who insisted the “revolutionary must … root [themselves] in concrete life, in order to draw upon it and verify their principles of action”.

For Fanon, intellectualising popular praxis demanded that militants shift their perspectives and critiqued themselves, as he explains in A Dying Colonialism:

It is necessary to analyse, patiently and lucidly, each one of the reactions of the colonised, and every time we do not understand, we must tell ourselves that we are at the heart of the drama–that of the impossibility of finding a meeting ground in any colonial situation.

He draws on Marx to think through the need for struggle within the struggle. In his 1960 notebooks, he asserts a need to “once again come back to the Marxist formula”.

“In Africa,” he maintains, “the countries that come to independence are as unstable as their new middle classes or their renovated princes [who] … suddenly develop great appetites.” For national liberation struggles to avoid bourgeois capture and for African unity to become concrete, Fanon suggests a need to “skip the bourgeois stage”:

For nearly three years I have been trying to bring the misty idea of African unity out of the subjectivist bog of the majority of its supporters. African unity is a principle on the basis of which it is proposed to achieve the United States of Africa without passing through the middle-class [bourgeois] chauvinistic phase.

Careful listening and critical engagement

In this view, the bourgeois nationalist is a chauvinist, implicitly corrupt, and the nationalist parties, fixated on the urban, simply want a seat at the colonial table. Some Marxists have dismissed Fanon’s commitment to taking the rationality of revolt seriously when it comes from political actors, such as the rural peasantry and the urban poor, as romantic. But for Fanon, listening carefully and critically engaging with the thoughts and actions of those often considered irrational and outside the established norms of politics is exactly the point. He rigorously criticised what he called the “opportunism” and the administrative attitude towards the people, who are quickly regarded as backward, just as rigorously as those he thought uncritically praised the people as “authentic”. Everything needed to be rethought, he said, in struggle and from the bottom up.

We should also recall that, by the end of his life, Marx viewed the peasantry not only as an ally to proletarian victory, but also as “possibly instrumental to still newer revolutions”, as Marxist scholar Raya Dunayevskaya puts it in Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution. She writes that “as he dug into the history of the remains of the Russian peasant commune, he did not think it out of the question that … a revolution could actually come first in backward Russia. This was in 1882!”

Like Marx, Fanon underscores the importance of movements challenging and contributing to theory:

The theoretical question that for the past 50 years has been raised whenever the history of underdeveloped countries is under discussion–whether or not the bourgeois phase can be skipped–ought to be answered in the field of revolutionary action, and not by logic.

Fanon’s discussion of permanent revolution as driven by concrete revolutionary action rather than abstract logic is a genuine contribution to a Marxist debate often bogged down by formulaic treatises. Struggles can’t wait for forces that conform to abstract theory to come on to the scene. Whereas Lenin considered the 1916 Easter Uprising in Ireland a “bacillus” for revolution, Fanon takes this one step further in The Wretched. No longer willing to wait for the sleeping European working class, it is up to people of the colonised world to realise a new humanism that has only been dreamt about in Europe.

Self-emancipation from below

Fanon insists the national form of social struggle is essential. But, at the same time, if national consciousness is not developed in a social and political programme, it becomes synonymous with the state, and political power becomes viewed through access to the colonial state apparatus. The nation-state remains an object of desire, even as the reality of national liberation becomes an empty shell.

Just as the urban-rural dichotomy served colonialism with its system of dual power and the incubation of “indigenous” centralising authorities, the national bourgeoisie is quick to seize the colonial state and perfect its machinery, often in terms of patronage and ethnicity undergirded with repression. State power represents not the nation, not even the party, but a fraction becoming identified with personal wealth.

As Marx puts it in The Eighteenth Brumaire: “All revolutions perfected this machine instead of smashing it.” It turns out that the anticolonial revolutions were no different. Fanon did not see the substitution of the party or state with the self-organisation of the oppressed as a model for liberation. He was committed to a new dialectic between the people and the state after independence in which self-emancipation remained the watchword, even if he understood that it was a tremendously difficult task.

In his final work, written as he was dying, Fanon’s pessimism about the colonial states he saw in various parts of Africa was matched by an optimism about the emancipatory possibilities of self-organisation from below. The oppressed as shapers of history was a matter of people “taking history into their own hands” and putting their minds together, the role of the political militant a commitment to “relentlessly teaching them that everything depends on them”. Perhaps this was an expression of what Marx called “the withering away of the state”. Far from liberation as a singular event, this “relentlessness teaching” was Fanon’s commitment to an unending praxis of radical humanism, or permanent revolution.