Stepping down from the bus on a usually quiet North Vancouver street, Stephanie Wilson can hear her destination before she can see it. A chorus of cheers and blaring horns beckon her downhill, where the road bends to reveal the gridlocked Trans-Canada Highway below.

It’s May 11, 2023, and every Thursday for the past 10 months, a group of protesters has gathered on the Mountain Highway overpass above the Trans-Canada, holding banners and signs in perfect view of the crawling rush-hour traffic. The language on some of the signs is vague: “Protect our kids” and “Love over fear.” Others make the message clear:

“There is no such thing as a trans child” and “Gender Ideology = Child Sex Grooming.”

Commuters respond with a symphony of horns, polite beeps punctuated by long semi-trailer blasts that reverberate through the valley. Whether the drivers are signalling support or dissent seems irrelevant to the protesters, who smile and wave at their captive audience like royals greeting the public from the balcony of Buckingham Palace.

Wilson, who lives in North Vancouver, isn’t there to join them—she’s there to challenge them.

Since debuting their transphobic signs, the Mountain Highway rally garnered widespread backlash from the community, the government, and even the B.C. Supreme Court, but their protests persisted. Seeing the demonstrations negatively affect her North Vancouver community and, fed up with the lack of action from the District of North Vancouver and police, Wilson finally thought,

Fuck it. I’m gonna go out there.

Wilson started as the sole intruder on the otherwise celebratory demonstrations, but it didn’t stay that way.

Throughout the summer, a counterprotest on Mountain Highway grew until, a year after they first appeared, the weekly protests stopped. As similar anti-2SLGBTQ+ demonstrations sweep Canada, the fight for one overpass holds lessons in how counterprotests can stymie growing far-right radicalism.

***

United by the 2022 Freedom Convoy and a shared disdain for pandemic health mandates, Canada’s far right has a new target: sexual orientation and gender identity, better known as SOGI. Often incorrectly framed as a mandatory curriculum, it is actually an optional resource called “SOGI 123,” endorsed by the B.C. education ministry to recommend age-appropriate 2SLGBTQ+-inclusive topics for K—12 students. Its intended purpose is to reduce bullying and discrimination.

Backlash against SOGI, a program that has existed in B.C. since 2016, has evolved into a widespread attack against queer and trans people—particularly the ability of trans kids to autonomously express their identities—in the name of “parental rights.” This movement, built on the assertion that parents have the right to know their children’s gender identity, ignores the reality that many queer and trans kids can’t freely express themselves at home.

According to Barbara Perry, director of Ontario Tech University’s Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism, far-right radicalism is a reactionary movement intended to not only maintain the status quo but to reverse the gains of historically marginalized communities. After the pandemic-induced surge in far-right activities, their shift to attacks against SOGI is the latest strategy to stay relevant and influential.

“Many of the people that we’re seeing in the anti-trans movement now are people who were very much a part of the anti-vax movement,” Perry explains.

They’re lurching almost from crisis to crisis and exploiting whatever public anxiety comes to the fore to boost their numbers.

Cait McKinney, a queer and non-binary scholar and assistant professor of communications at Simon Fraser University, says that trans youth emerged as the far-right’s new target as a backlash to the gains of the community over the last decade.

“We have ingrained in us the belief that being represented and being visible is a gateway toward rights,” McKinney says.

To some extent that is true for trans folks, but that kind of heightened visibility also comes with heightened scrutiny and people are made much more vulnerable to transphobia, criticism, and violence.

The 1 Million March 4 Children, a series of Canada-wide protests held last September against SOGI education and gender-affirming care, saw crowds gather in more than 50 cities across Canada. While the protests included a diversity of people, their far-right roots were on full display—a flag featuring a swastika flew in Ottawa, Nazi salutes were spotted in Kelowna, and known white supremacists participated in Vancouver. While attendance wasn’t close to the promised one million and largely dwarfed by counterprotesters, the real danger has emerged as politicians reproduce the rally’s transphobic narratives through policy.

In October, the Saskatchewan government passed the The Education (Parents’ Bill of Rights) Amendment Act, 2023, controversially invoking the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to push it through. The law requires parental consent before a child under 16 can change their pronouns at school, mirroring a similar policy introduced in New Brunswick last summer. In January, Alberta premier Danielle Smith announced a slew of policy changes targeting transgender youth, including limitations on students’ ability to change their name or pronouns without parental consent, restrictions on access to gender-affirming care, and a ban on trans women competing in women’s sports leagues. At the last federal Conservative Party convention, MPs approved support for a policy that could potentially ban gender-affirming care for youth, signalling the risk that these policies could later manifest at the national level.

“Discrimination against trans folks and particularly trans kids has become the issue that the right is using not just to unite themselves but also to recruit voters who might be in the middle of the political spectrum,” McKinney explains.

They’re doing that through a campaign of mis- and disinformation. The slogan ‘gender ideology equals child sex grooming’ gets right at the heart of where that mis- and disinformation lies.

McKinney argues that the most effective strategy going forward is for the trans community and their allies to also target this moveable middle in their organizing by fostering trans-inclusive environments and challenging disinformation when it arises. “What matters and who we can target in our organizing are people who don’t have accurate information about trans folks and trans health care and the only information they get is from anti-trans people organizing protests in their communities,” they say.

Counterprotests matter because they show Canadians […] that [transphobic protesters] are a fringe minority and that, in fact, the majority of Canadians support trans people.

***

Wilson has been tracking and documenting the far right since the 2022 Freedom Convoy, attending events, infiltrating chat rooms, and sharing her findings online. With COVID mandates dwindling, many saw the overpass protests more as a cringe-worthy reminder of kooky anti-vaxxers than a substantial political threat.

Wilson knew better.

“There’s this real perception that Freedom far right isn’t real far right, which is really frustrating,” she says.

They don’t look like neo-Nazis marching through the streets but once you start getting into what they’re saying, you start to see just how bad it really is.

On North Vancouver’s Mountain Highway, she watched the shift from anti-vax to anti-trans play out in real time. The weekly protests started in July 2022 as a Freedom Convoy—inspired rally, but by spring 2023, they took on SOGI as their new target. Some weeks, the protest would gather up to 30 attendees. “This is a very deliberate attempt to erase what it means to support queer and trans rights in B.C.,” Wilson emphasizes,

And that’s really worrying to me.

When she first interrupted the overpass protest on May 11, 2023, Wilson wasn’t the only new addition to the scene. Zip-tied to the same guardrail where protesters had been hanging their banners was a B.C. Supreme Court injunction sought by the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure ordering the group to cease their occupation of the overpass. With the injunction came the RCMP, theoretically there to arrest anyone breaching it. The rally didn’t hang their usual banners from the overpass, but they were still there, holding signs and cheering with the honking traffic.

Despite the injunction, the weekly protests continued, and no arrests were ever made.

Wilson first visited the overpass to keep an eye on the protesters, but she returned week after week to monitor the police response—or rather, the lack thereof. The Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure and District of North Vancouver city councillors and residents repeatedly called on the RCMP to enforce the injunction and remove the protesters. The RCMP insisted it wasn’t so simple.

The injunction has three terms: no person can occupy the area, nothing can be affixed or hung from its structures, and no person can intentionally disrupt the travelling public. According to Constable Mansoor Sahak of the North Vancouver RCMP, the language of the injunction required that all three terms be infringed simultaneously for it to be technically breached. He added that while the possibility of hate speech was considered, the RCMP ultimately concluded that the demonstrations didn’t meet the legal requirements for any criminal charges. “The protesters were very careful about how they worded their messaging. It was just right on the line of hate speech, but it didn’t meet that threshold,” Sahak says.

Paula Neufeld, a youth counsellor who lives just a few houses from the overpass, would disagree. As the mother of a trans child, she took particular issue with what she saw as the group’s hateful message—enough that, one sunny Thursday in June, she threw on a rainbow T-shirt and brought her own sign to the overpass. Its design was humble—black sharpie on a piece of cardboard she had lying around the house—but its message was firm:

More love. Less Hate. #AllChildrenMatter.

Ignoring harassment and provocations from the regular protesters, Neufeld returned to the overpass with her sign the following Thursday. And the next Thursday. And the one after that. “I felt that people needed to see support,” she says.

Because what if a gay or trans person is in one of those cars and they’re coming down and they see all this hate, all this misinformation? How badly would that make them feel?

By early July, other counterprotesters, strangers to both Neufeld and Wilson, serendipitously started coming to the overpass. “Most of us just wandered down to the overpass alone or with a couple of other people because we were upset and somehow we all came together at the same time and put on a fight,” Wilson recalls.

Where a Supreme Court injunction and RCMP failed to stop the occupation of the overpass, the small but mighty counterprotest eventually did.

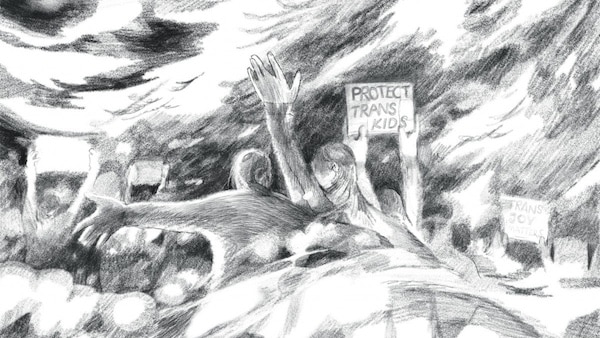

On July 13, 2023, the one-year anniversary of the Mountain Highway rally, both sides of the protest came out in full force. Commuters accustomed to the regular weekly display of transphobic signs were met instead by Pride flags defiantly flowing and Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” booming from a speaker.

“That was a really demoralizing one for [the transphobic protesters],” says Wilson. “I kind of think that might have been the straw that broke their back.” The following Thursday, when the counterprotesters returned, they were alone on the overpass. While the far-right group abandoned Mountain Highway, it was several weeks before their rallies left North Vancouver. A small group of counterprotesters, including Wilson, continued to disrupt their new locations on nearby overpasses and major intersections. But by fall, the group had moved across the Second Narrows Bridge to a new overpass, in a new city.

Wilson’s guess that the counterprotests chased the original protesters out of North Vancouver is more than mere assumption. Robert Webb, the man who started the Mountain Highway rally, admitted from his new protest spot on Burnaby’s Willingdon overpass last October that the consistent rainbow flags pushed his group off Mountain Highway. “Tran-tifa ran us out, unfortunately,” Webb laments.

It’s a real shame we can’t use that one.

He reported that in the months since the protest’s move to Burnaby the group had been free from counterprotesters. Wilson says the group’s appearances this year have been more sporadic, but she still occasionally spots the “Gender Ideology = Child Sex Grooming” banner on the Willingdon overpass. For the community in North Vancouver, it’s a bittersweet victory. While the visibility of the protests is gone, much of their sentiments remain.

“We haven’t solved the problem of right-wing extremism in North Vancouver, but we have made it a little bit more uncomfortable for them to be open about it,” says Wilson,

because someone finally said, ‘Actually, you can’t be here and you don’t belong here.’

But Wilson also acknowledges that communities need more than counterprotests to initiate real change.

While the Vancouver counterprotest greatly outnumbered the original 1 Million March protesters, in Surrey, B.C.’s second highest populated city, the roughly 100 counterprotesters were overpowered by more than 1,000 anti-SOGI protesters, according to Lee, an organizer and co-founder of the Surrey Dyke March. When another anti-SOGI rally was planned for October, Lee says the Surrey Dyke March made the decision to not formally counterprotest out of safety concerns.

Lee, whose last name is omitted to protect their identity from potential doxxing, emphasizes how Surrey’s intersectionally marginalized demographic and dual police forces pose additional challenges in organizing. “Impoverished folks, working-class folks, racialized folks, and others dealing with multi-system oppressions organizing and having the time, energy, and access to the community is very, very challenging,” they explain.

To mitigate these challenges, Lee says Surrey needs to invest in community support, resources, and spaces for the 2SLGBTQ+ community.

We need representation in the City itself. We need resources. We need funding for queer spaces to exist and allow us to organize and connect with each other in a safe and accessible way.

The safer the community feels, the more prepared they can be for when the next hate-filled protest arrives. For Wilson, that’s the real victory of organizing against anti-2SLGBTQ+ hate. “The whole point of right-wing extremism is you take away the humanity from people. So the way to counter that is to bring humanity back into communities,” she says.

***

Lesley Wood, an associate professor of sociology at York University who specializes in protests and social movements, has found in her research that when counterprotests are consistently larger and more diverse, right-wing protesters stop mobilizing. Even though they never outnumbered the original protesters, the Mountain Highway counterprotest still successfully dispersed the far right from their community because they made the community’s dissent visible, expanding the counterprotest effect to the passersby supporting them.

“With basic counterprotest, you’re trying to delegitimize, you’re trying to get the message out, you’re trying to make them look like a minority. But you’re also trying to inspire others to speak up,” Wood explains. “Counterprotest creates a line in the sand. And it says, ‘Which side are you on?’” In North Vancouver, the public’s choice for the side of trans liberation deflated the protesters from continuing their hateful display. As Wilson puts it,

The story of North [Vancouver] is really, you don’t have to outnumber them, you just have to stand up.

This year, the anti-trans protests have become less frequent on their new Burnaby overpass but in February, the group returned to Mountain Highway for the first time in months, with new signs and a new ideological target. This time, the group took issue with harm reduction and safe supply, sporting a large banner asserting that the B.C. government is providing fentanyl to children. Despite this pivot, the anti-trans sentiments remained. Other signs spotted on the overpass this year read “Protect childhood innocence” and “Men do not menstruate.”

When the protest group made their return to Mountain Highway, so did the counterprotesters. Even though their victory may seem short-lived, Wilson doesn’t discount the impact of the counterprotest on the scale of the returning group. She sees only three to four protesters regularly showing up to the overpass each week. The far right’s anti-trans crusade is far from over and after fighting back against their rising influence in her community, Wilson is urging others to do the same.

“I don’t think we can rely on institutions to protect communities and the Mountain Highway is evidence of that,” she emphasizes.

Counterprotesting fascist action is the only way forward.

Phoebe Fuller (she/her) is a journalist and master’s student at the University of British Columbia. Her writing focuses on labour issues, 2SLGBTQ+ identity, and pop culture, and has appeared in Xtra Magazine, PressProgress, and the Georgia Straight, among others.