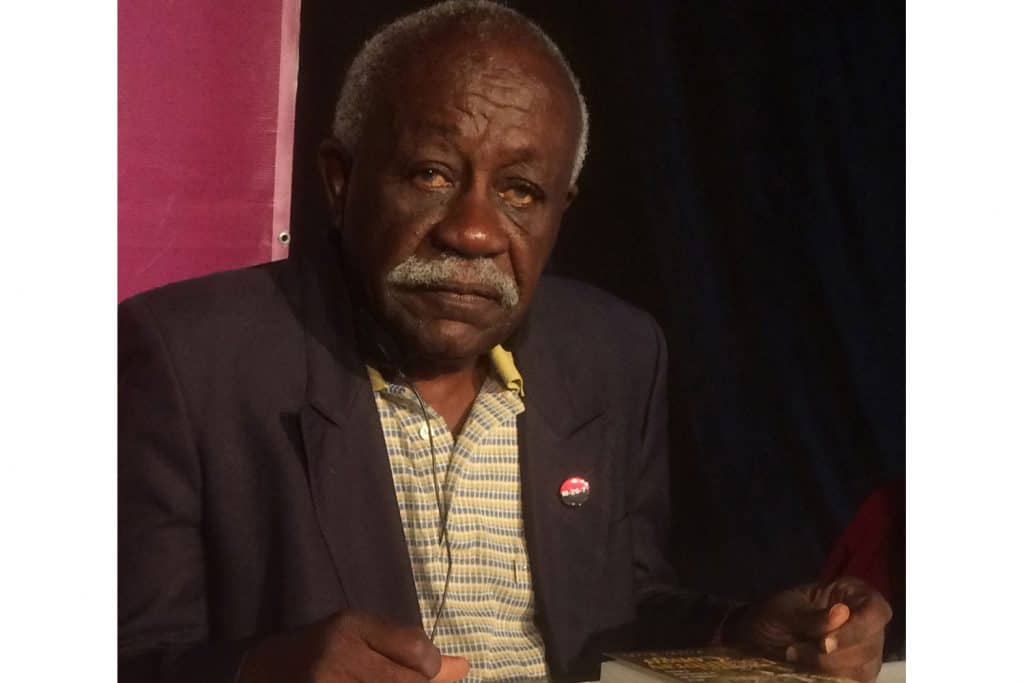

Victor Dreke is a former colonel of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces who fought alongside Che Guevara during the Cuban revolution’s decisive battle of Santa Clara. In 1965, he joined Guevara’s rebel training project in the Congo as his second-in-command. Born in 1937, Dreke had joined the Cuban revolutionary movement at the age of 15. Following the triumph of the revolutionary war in 1959, he participated in several operations against counterrevolutionary bands, including the 1961 mercenary invasion at the Bay of Pigs. As of 1965, Dreke has been responsible for the training of internationalist volunteer combatants and the organization of Communist Party units within the armed forces. He headed Cuba’s military mission in Guinea-Bissau and Guinea-Conakry 1966-68 and 1986-89, and regularly returns to Africa as the vice president of the Cuba-Africa Friendship Association. He holds degrees in political science and law.

Recently, Victor Dreke and his wife Ana, a Cuban physician who established the first medical school in Guinea-Bissau, toured Europe for taking part in commemorations of Che Guevara’s assassination 50 years ago. The interview with them was conducted at the Cuban Embassy in Brussels by Ron Augustin.

People who are familiar with your track record mainly associate you to your activities in Africa, starting with the Cuban military training mission in the Congo that was headed by Che Guevara and yourself. At the time, you were the first of that Cuban contingent to arrive in the Congo, hence your nom de guerre Moja, Swahili for Number One. Why did the Cuban leadership agree to help the Congolese rebels by sending them a column of 128 military instructors?

Victor Dreke: In order to understand the presence of a Cuban military contingent in the Congo, it is necessary to recall what was happening at the time. A few years earlier, the Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba had been murdered. Other leaders of revolutionary movements had also been murdered. In Africa, seventeen former colonies had formally attained their independence, but all they really got was a flag and an anthem, while they continued to be oppressed and exploited by the imperialist powers. Other countries had to fight bloody independence wars that lasted into the 1970s and 1980s. The African liberation movements were in full disadvantage as compared to the troops they were fighting against, which consisted of mercenaries from all over the world. In the Congo, the Belgians were bombarding villages, terrorizing and killing civilians, in order to destroy the followers of Patrice Lumumba and regain control by bolstering Mobutu’s troops. Increasingly, Mobutu and his mercenaries received military support from the United States as well.

As a member of the Cuban government, Che traveled through Africa during the first months of 1965. He met with government officials and several leaders of liberation movements. As he described in detail in his report on our mission in the Congo (Ernesto Che Guevara, Congo Diary [Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2012]), many of these “freedom fighters” asked for help in terms of military advice and logistic support. At the same time, the leaders of the Lumumbist movement in the Congo had requested the possibility to send 30 of their officers to study in Cuba. Basically, the Cuban leadership was in agreement, but when these requests were analyzed, they came up with another proposal. In our view, it would be more useful to send Cuban officers to Congo to train the combatants on the spot. For us, it was not the same to organize training in Cuba or in Africa, because of the characteristics of the terrain, different conditions, and also to have Cuban instructors participate in the first actions, in real combat situations. Once the Congolese had accepted our proposal, Che volunteered to head this trip. That’s how on April 1, 1965, the first group including José Martínez Tamayo (Mbili) and myself left Cuba for Tanzania, and April 24th we disembarked on Congo territory.

What was the underlying concept of the undertaking in the Congo?

Victor: Our basic concept was that the best training is done on the ground, in combat, under realistic conditions. In the Congo, Cuban instructors lived and fought together with Congolese combatants with the perspective of developing the first “mother columns” that would eventually be able to spread and form other columns on their own. Combatants from other African liberation movements were to benefit from this training concept by joining us there in a later stage. Actually, a number of Rwandans had already integrated the Lumumbist guerilla forces we were working with. The training program was developed on the spot and consisted of reconnaissance marches, organizational issues, survival tactics, attacks on military convoys. We organized language courses, and Che even held classes on Marx’ Capital. As I pointed out in my own book (From the Escambray to the Congo [New York: Pathfinder Press, 2002]), the training included ourselves, Cubans, and has benefited those who, a year later, joined Che’s undertaking in Bolivia, which was based on the same concept, basically.

In his report on the Congo experience, Che Guevara speaks about “the inauguration of the International Proletarian Army”, a perspective he developed further in his last declaration on the creation of “two, three, many Vietnams”. A perspective largely exceeding the Congo project. What discussions did you have with him on that?

Victor: We had talks about this. Che’s involvement in the Congo and Bolivia were based on his experiences in Guatemala and Cuba, with a far-reaching strategic, tricontinental, perspective. We were all in agreement with the fact that the Africans needed training, to enable them to defend themselves. As you know several troops were operating in Africa, made up of mercenaries, not just in Congo but also in other parts of Africa. At the same time imperialist forces were attacking Vietnam, as a revolutionary example that had to be crushed. So what we tried to do was to help unite peoples who were fighting for the same cause, ultimately to join all African peoples so they could defend themselves against imperialism. It was one of the objectives and principles of the Cuban revolution, and still is, under different characteristics, to assist all countries who demand help. Nowadays we are also sending armies, albeit armies made up of doctors. At the time we were willing to share our blood for Vietnam, as much as we now try to unite and defend peoples in the health sector, among other things. For us, this was not just a slogan but something we were willing and ready to do. It was a decision by the Cuban leadership to support unity wherever possible, in order to defend Cuba, to defend Vietnam, Guinee Bissau, any fighting country. Imperialism wanted and wants to crush us, the revolutionary example. Against imperialism, we had and have no other choice but to unite.

Ana: In order to understand what Victor has said I’d just like to add the following. There were two ways of thinking coming together in the revolutionary process we have witnessed, the one of Che and the one of Fidel. When they analyzed the situation of the Cuban revolution and the strategy needed to continue forward, and this is what Victor shared with me regarding the talks that Che had with his troops, the first principle was solidarity with all oppressed peoples in the world. Che had traveled throughout Latin America before joining the Cuban revolution, witnessing generalized misery and exploitation while gaining his political experience and insight. Fidel had experienced similar conditions in Cuba, which he described in his famous “History will absolve me” speech. They were both very conscious that the revolution had to be defended by weakening the imperialist forces and that these forces could only be weakened by attacking them at as many points as possible. When Che went to the Congo, Fidel supported that perspective and continued to do so, also in other fields, such as health, education, and sports. This solidarity at the military and social levels started in 1963 in Algeria, and all these actions have had the same purpose, creating this force of unity, in order to weaken imperialism. After Lumumba’s assassination, Congo was a logical place to begin, bearing in mind that it was a request made by the Congolese, and Che’s musings on creating “two, three, many Vietnams” correspond exactly to this line of thinking.

In parallel with your mission in the Eastern Congo, a Cuban unit directed by Jorge Risquet et Rolando Kindelán was stationed in Congo-Brazzaville, to help its government defend itself against incursions by mercenary troops and to train MPLA guerillas from Angola. Were the two missions coordinated, or was there any contact between these and Pierre Mulele’s rebel group fighting in the Western part of the Congo?

Victor: There was no contact whatsoever between our group and the Cubans in Congo-Brazzaville. Communication was much more difficult than nowadays, and in those days we were unable to establish any contact with them. We followed a rule of guerilla warfare Raul Castro had taught us: although we are physically apart, we think the same. In January 1965, Che had met Agostinho Neto from Angola and agreed to support the MPLA, which at the time had bases in Congo-Brazzaville. In addition, the country’s president Massamba-Débat had asked Cuba for help after Mobutu’s troops had tried to kill him. Che wanted to meet Mulele, but at the time we never knew where to find him. Eventually, Mulele showed up at our Embassy in Brazzaville. Our Ambassador warned him not to meet Mobutu who had offered him a peace pact, yet he went and got assassinated.

After your departure from the Congo and a short stay in Cuba, you returned to Africa early 1966 with a unit of military instructors to help the PAIGC combatants in Guinea-Bissau led by Amilcar Cabral. Can you tell us something on your time there, which lasted until 1968, before returning there in the 1980s, and particularly on your relationship with Cabral?

Victor: Cabral and I, we were like brothers. I had the chance to meet and know a great African leader. A man of integrity, simple, sharp. Che had met him several times and had told me about him. Cabral was respected not only in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, but by the liberation movements of the entire continent. The Portuguese tried to bribe him by offering money, but he refused. That’s why they assassinated him too. We were in a guerilla camp in Guinea-Bissau when we learned of Che’s death in Bolivia, and the disappearance of other comrades with whom I had fought in Cuba and the Congo. These were very tough moments for me, as for Amilcar Cabral, who in my mind remains very much connected to these events. As a reaction to Che’s death, Cabral organized a military operation against several Portuguese garrisons simultaneously, a joint operation by Cuban and PAIGC forces under the name “Che has not died.”

Amilcar Cabral and Mehdi Ben Barka were involved in the preparations of the Tricontinental Conference, an idea they had developed together with Che during his travels in Africa. What was the relationship between the conference and Cuba’s support to liberation movements?

Victor: Ben Barka was murdered during the preparations for the Tricontinental, which was a meeting attended by revolutionaries who were willing to fight for the independence of their peoples. At this meeting in January 1966, organized by the Organization for the Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America (OSPAAAL), another meeting was convened in the Summer of 1967 under the banner of the Latin American Organization of Solidarity (OLAS), bringing together most of the guerilla movements fighting in Latin America at the time. The significance of these two events is that they were able to gather a large number of revolutionaries. In his message to the Tricontinental, which he wrote just before leaving for Bolivia, Che outlined a strategic perspective, stating that imperialism, as the last stage of capitalism, must be defeated in a large global confrontation. What we need and what we continue to struggle for is unity in the fight against imperialism. In that sense, our support to other countries is part of our own struggle.

In your view as a long-time member of the military and party member, what are the differences between an army defending socialism, such as in Cuba, and armies defending capitalist interests?

Victor: There are major differences. Capitalist armies have been involved in murder. Capitalist armies exist to form a wall between the people and those in power. Their soldiers are being drilled with slaps, kicks, shouts. They are forced to do things that have nothing to do with military defense, they are brainwashed into blindly following orders without asking questions and without actually knowing what they are defending or fighting for. In Cuba, in a way, the entire people belongs to the military, not by law, but from the heart. Our soldiers know that whatever they do, they do it out of respect for the freedom of the people, their discipline is a conscious one. Right from childhood, in the pioneer movement, they have learned to ask questions, to respond actively to the things they hear. Their education enables them to know and understand what is happening in the world. This is why Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces conducted multiple humanitarian missions as well.

You met Che Guevara for the first time during the revolutionary war in the Escambray mountains. Can you tell us under which circumstances?

Victor: I joined Cuba’s revolutionary youth movement on my 15th birthday, the very day of Batista’s military coup in March 1952. We organized all kinds of actions against the Batista regime, and when the July 26 Movement was formed in 1955, I became head of sabotage actions for Sagua la Grande, one of the country’s largest sugar-producing regions. Our group functioned as a link between the student movement and the struggles of the sugar workers, who were among the most combative at the time. By the end of 1957, I had to go into hiding and signed up with a guerilla front in the Escambray, which had been organized by the March 13 Revolutionary Directorate. In October 1958, I was in a camp the Directorate had set up in Dos Arroyos, a few days after I had been wounded in combat when our unit had attacked the town of Placetas, some twenty miles ahead of Santa Clara. Che had reached the Escambray a few days before, and used the camp to reorganize his and our troops for what was to become one of the last battles of the revolutionary war. We had already told them that everything in the camp was at their disposal, and yet Che asked me if he could borrow my typewriter “just for a moment”. He checked my wounds and told me they were healing fine. “You’ll be able to fight again soon.” That’s how I got to know him. I’ll never forget those first moments. Ever since, he has been like a brother to me.

Fifty years after his death, what, in your opinion, is Che Guevara’s significance today?

Victor: For me, Che signifies a human being in the revolutionary struggle of today and of tomorrow. Che was a true revolutionary combatant defending the cause of socialism. He convinced by his own example, his simplicity, his moral values and revolutionary ethics. He practiced what he advocated, and left us with a rich legacy of theoretical considerations, including contributions to the political economy of socialist transition and thoughts on guerilla tactics, economic planning, and the role of the individual in building a socialist society. Wherever a human being stands up to fight capitalism, Che’s presence can be felt.