Here’s an experiment for you—ask five people if they know where the “millennial” label came from. Chances are that none of them will know. In fact, not much is known about the meaning of the label, other than it being a synonym for “young people” or a catch-all term for those who are “x-to-x” years old.

Where did the millennial label come from and why aren’t its origins and meaning analyzed in more depth?

Millennials Came From…A Book?

A simple online search reveals that the millennial generational label originated not from some sort of a scientific consensus, but from William Strauss and Neil Howe’s 1991 book titled Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. If you buy into the millennial and other generational labels, which is perhaps the most obvious goal of such books, Generations is your Bible.

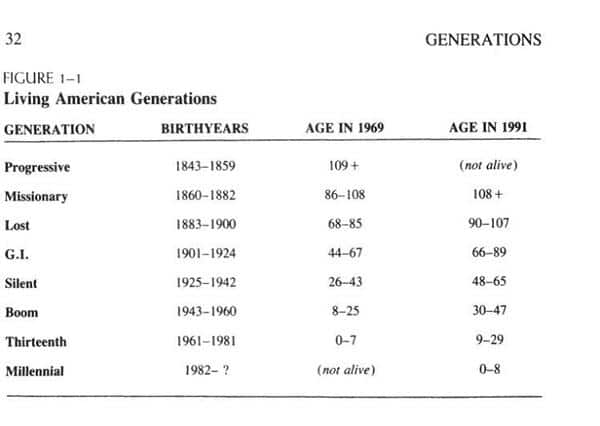

Figure from Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069 by William Strauss and Neil Howe (1991)

Strauss and Howe illustrated their ideas through figures like the one above, taken from page 32 of Generations. Eventually, they set 1982–2004 as the start and end years of the millennial generation.

At the time, Strauss, who passed away in 2007, was director of Capitol Steps, a satirical singing group, and previously worked as a policy director for the U.S. Congress. Howe worked as a senior adviser for the Concord Coalition—an organization that is dedicated to addressing “long-term challenges facing America’s unsustainable entitlement programs,” and senior policy adviser for the Blackstone Group—a multinational firm that specializes in private equity, credit, and hedge fund investment strategies.

A cursory analysis shows the writing duo’s connections to “deficit hawk” billionaire Peter Peterson, with whom Howe co-wrote a book in 1989 titled On Borrowed Time: How the Growth in Entitlement Spending Threatens America’s Future , as well as “alt right” documentarian and Trump’s chief propagandist Steve Bannon, whose 2010 documentary ” Generation Zero,” produced by Citizens United Productions, was inspired by Strauss and Howe’s work.

In 1997, Strauss and Howe published The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy, which expanded their ambitious theory that analyzes modern history in cycles, each one lasting about the length of a human life and each composed of four eras, or “turnings.” If we were to believe Strauss and Howe’s prophesy, then millennials are a “hero” generation currently living in “the crisis” turning. As it turns out, “the crisis” might last until 2030, according to Howe.

Perhaps, like me, you didn’t know that the millennial label originated from the books of two, white American amateur historians, whose work includes prophesies and repeating historical cycles. I believe this is by design.

When we take into account the private engineering of the label and its use by billionaires, “alt right” propagandists, and virtually every corporate media in the U.S., it makes sense that the facts mentioned above are rarely discussed on corporate media. Since its creation, the millennial label has served as an instrument to divide society, diffuse government and corporate accountability, and create stereotypes about millions of people.

As pioneers in the field they essentially created, Strauss and Howe have no trouble addressing the weak points of their generational theory. In fact, they admit that their analysis does not mean generations are “monochromatic.” Their counter argument is that, when considered as “social units,” generations are “far more powerful than other social groupings such as economic class, race, sex, religion and political parties.”

In Millennials Rising, published in 2000, Strauss and Howe defend the inherent selectivity in their work by arguing that generations are not about the “bits and pieces,” but about the “social and cultural center of gravity” of a generation.

“For any new generation, like for any young and thriving and mortal organism, its direction of change can be more important than its current location,”” they write, “It is a generation’s direction that best reveals its collective self-image and sense of destiny.”

Who gets to define where that “social and cultural center of gravity” may or may not fall, or what that “direction of change” may be? Well, apparently Strauss and Howe do. In addition to defining the millennial and other generations, the two amateur historians/demographers/economic analysts take the liberty to also define the economic factors which have shaped the lives of millennials.

In Millennials Rising, they attribute the growing gap in average incomes to the “rise of knowledge-intensive innovation and quickening of immigration and global trade,” which has “widened the market-determined spread between high and low wages.”

Later in the book, Strauss and Howe claim that the millennial black-white disparity is “mostly due to the lower share of black kids growing up in two-parent families than white kids.” They see a contrast largely between two sets of kids—those with “two-income Boomer parents-highly educated soccer moms, bursting stock portfolios, and gift-giving grandparents” and those with “one-income Gen-X parents, many of them never-married black moms or recent Latino immigrants.”

Interestingly enough, they fail to mention how government policies can mitigate the effects of inequality to the poor and the middle class. In addition, they argue that “family structure unquestionably trumps the economic aspect of race alone” (a trademark of right-wing organizations like the The Heritage Foundation).

Such incomplete and reductive analysis usually promotes the viewpoint that personal preferences are the main drivers of inequality. This is how, instead of analyzing problems at a structural level, commentators get to single out “never-married black moms” and “recent Latino immigrants” when talking about inequality (and in this case put generational labels in the mix to sound credible).

This explains why those in the business of defining generations are so elaborate in interpreting the history around said generations. These kinds of historical interpretations highlight the real value of the label as an instrument of propaganda that can mold our perceptions of government, culture, and ourselves.

Another common right wing talking point—that “welfare” is bad for America—is also observed in books about millennials, such as the 2016’s When Millennials Rule. In the book, David and Jack Cahn, brothers and self-described millennials, argue that young Americans don’t approve of welfare programs and would put them “on the chopping block” if given the chance. Unsurprisingly, some of the data in the their book comes from a Koch brothers-sponsored organization, Generation Opportunity (more on them later).

This begs the question: is most content about millennials really about millennials? Given the voyeuristic nature of everything that is said about millennials, the lack of truly bottom-up organizations that portray diverse millennial perspectives, and the common way of defining millennials as “young” or “18-to-36 years old,” it becomes apparent that the top-down creation of the label has also created a top-down reflection of the people it claims to characterize.

As shown in the examples above, the real value of the millennial label as it is commonly used is not about the potentiality of the millennial generation or even the actual experiences of the people behind the label, but about the opportunity to use the term as a “hook” in selling and promoting a certain ideology and narrative about millennials.

Who Gets To Package And Sell Millennial Narratives? (Spoiler: It’s Not Millennials)

The popular framing of the millennial identity solely in terms of biological factors allows commentators to reduce the public’s understanding of millennials to surveys and statistics, rather than the real-life actions and perspectives of the people behind the label. This transforms the millennial narrative into questions of whose data and interpretations are better, or who is a millennial and can talk about all millennials, rather than analyzing problems from the perspective of millennial political power and representation.

This is how the “millennial problem” is diverted from one that requires bottom-up, grassroots solutions based on national surveys related to generational differences that cut across the full range of socioeconomic status, to one that is delegated to political influencers, marketers, and generational experts who often use one time polls to “distill” the millennial narrative for the rest of us.

These “experts” spread the gospel of generations, and with it, the political and corporate ideologies that usually follow efforts to hijack the narrative of millions of people.

One may draw parallels to the work of Edward Bernays, the “father of public relations,” and his advocacy for using “third parties” to engage in propaganda. “If you can influence the leaders, either with or without their conscious cooperation,” Bernays wrote in his 1928 book Propaganda, “you automatically influence the group which they sway.”

There are plenty examples that show how individuals and organizations manipulate the millennial narrative. Some “millennial-led” organizations such as GenFKD and Generation Opportunity use the millennial label to promote trickle-down economics (more recently through their overwhelming support for the 2017 GOP tax bill). In December 2017, Generation Opportunity applauded FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s decision to gut net neutrality. Here’s a statement by Generation Opportunity’s director of policy engagement on the FCC decision:

“Before the FCC’s power grab to regulate the internet as a utility, the internet was one of the most dynamic and innovative parts of our society. Net neutrality is a heavy-handed solution to a problem that does not exist for customers. Now, my generation, which created many of the most important online companies, will keep building new products to make everyday lives better using a freer internet .”

In true Bannon fashion, Generation Opportunity claimed that criticisms of Pai come from “intellectual elitists in Hollywood, not those who are actually knowledgeable on the subject.” For the record, this list of “intellectual elitists” includes Vint Cerf, Tim Berners-Lee, and Steve Wozniak, all of whom have criticized the decision to strip net neutrality.

There are many other examples of “millennial-led” organizations that manufacture support for right wing policies. “Long overlooked, millennials get boost from GOP tax plans,” claimed the CEO of GenFKD on the eve of the GOP tax bill.” “Why millennials should get behind Trump’s tax reform,” pondered the policy director at Generation Opportunity. “Millennials can be thankful for the GOP’s tax reform proposal,” concluded Abigail Marone from Americans For Tax Reform. Other Koch-funded nonprofits, such as Young America’s Foundation, use their “millennial credibility” to promote right wing talking points through a roster of mostly non-millennial speakers.

Such examples expose how politically motivated networks use the millennial label as a way to sell a certain ideology, especially by employing self-described millennials who use their “millennial status” to appear as if all millennials support their case, when in fact what they are really doing is using selective data to manufacture millennial consent .

Right-wing financiers such as the Koch brothers understand this back-door to influencing the narrative of younger generations, as evidenced by their funding of organizations like Generation Opportunity. The Peter G. Peterson Foundation also finances millennial-led organizations and “astroturf” campaigns that promote austerity measures to ” the next generation.” All in all, the hijacking of the millennial label, mostly by “older” white men, seems to be a common occurrence. Often, the label is used not to understand millennials, but to benefit financiers, lobbyists, and marketers who attempt to speak on behalf of the people behind the label.

The main trick of such organizations is taking selective data from a survey, usually done by themselves, and using it to argue on behalf of all millennials. For example, according to a Gen FKD survey (conducted via Survey Monkey), 82 percent of millennials, defined as young adults ages 18-34, believe the U.S. needs tax reform. The organization then uses this “national Millennial survey” of 502 young adults to argue in favor of right wing policies, such as the GOP tax plan.

Such reductive applications of the millennial label expose those who use it to manipulate public opinion as the new faces of the same old attempts to promote failed “trickle-down” economics ideology.

How did generational narratives become a weapon for the political and corporate elite? The failure to investigate and expose the origins and uses of the millennial and other generational labels is based on a number of factors.

Millennials as Perpetually “X-to-X” Years Old

First, we have been indoctrinated to believe that a single word can somehow characterize the experiences of 80 million people. This is mostly due to the popular description of millennials as “x-to-x years old.”

In fact, most commentators who use the millennial and other generational labels often discuss birth cohorts instead of generations, which is why most content about millennials reads like ageism with extra steps. While grouping generations by age is an easy way to package and sell generational “insights,” it only provides a limited understanding of millennials.

An analysis of Karl Mannheim’s Theory of Generations, posed in his 1923 essay The Problem of Generations, reveals a much more complex understanding of the concept, before previous research on the topic was co-opted into the billion dollar marketing industry we know today. For example, Mannheim asserted that generations are stratified by sub-generations and external factors, such as location, culture, and class. Perhaps most interestingly, Mannheim stressed that not every generation even develops an original and distinctive consciousness.

Mannheim stated that people should distinguish between the “social consciousness and perspective of youth reaching maturity in a particular time and place,” what he described as “generational location,” and a “concrete bond between members of a generation,” which he described as “generation in actuality:”

If we speak simply of ‘generations’ without any further differentiation, we risk jumbling together purely biological phenomena and others which are the product of social and cultural forces: thus we arrive at a sort of sociology of chronological tables (Geschichtstabellensoziologie), which uses its bird’s-eye perspective to ‘discover’ fictitious generation movements to correspond to the crucial turning-points in historical chronology .

It must be admitted that biological data constitute the most basic stratum of factors determining generation phenomena; but for this very reason, we cannot observe the effect of biological factors directly; we must, instead, see how they are reflected through the medium of social and cultural forces. (p. 31, The Problem With Generations)

Compare those sentiments to how generational narratives are engineered in the media today, when social scientists and marketers compete to define generations even before their alleged members are born.

The ridiculous notion of defining members of generations before they come of age also has an explanation. Since we are shaped by events that happen during our youth, it makes sense that people who engineer generational theories do so before those generations are exposed to the “medium of social and cultural forces.” The point is to create an environment where millennials and other generations grow up with the idea of “being a member of X generation,” which ironically shapes their understanding of the generation before they even have an opportunity to “enroll.”

Understandably, Mannheim’s ideas, which essentially promote a deeper understanding of generations, are of no interest to organizations that project millennials as a homogeneous group of people who are “18 to 36 years old.” Adding any complexity to the “common” ways in which millennials are defined would make it hard to sell and target the group as a whole, which is the whole point of the generation industry. This is why those who talk about and represent millennials often stick to defining the generation in biological terms.

“If we want to understand the primary, constant factors, we must observe them in the framework of the historical and social system of forces from which they receive their shape,” writes Mannheim. In a sense, those who define generations solely in biological terms, do so precisely because they can they shape the generation’s historical and social factors around their limited definition.

The funding behind the millennial industry’s information outlets—from marketing, consulting, and spreading political and corporate ideologies, to producing click-bait articles for ad revenue—points to a concentrated effort to use the millennial label as a conduit for propaganda, rather than an opportunity to understand millennials.

An Instrument for the Ruling Class

By perpetuating the dumbed-down understanding of millennials described above, the political and economic elite in the U.S. are able to avoid addressing the actual reasons why people don’t trust them. In fact, both sides of the political duopoly and their media outlets often discredit and belittle millennial narratives that don’t fit the status quo.

“Democrats and the GOP both have a millennial problem,” states an article in The Washington Post, citing a NBC News/Genfoward survey according to which “a third of millennials said that neither party cares about people like them” and “more than 4 in 10 millennials identify as independents.”

The article points out that a sizable number of nonwhite millennials—African American (31 percent), Asian American (30 percent) and Latino (37 percent)—claim that “the Democratic Party does not care about people like them.” According to the survey, 55 percent of white millennials say the same thing. “White millennials are also the only racial subgroup to hold a more unfavorable view of the party (54 percent) than favorable (33 percent),” states the article. Known for its troubles with attracting minority voters, Republicans face similar hurdles with white millennials, who hold “nearly equally unfavorable views of the Republican Party (53 percent).”

Given these results, it looks like both parties have more than a problem with “those aged 18 to 34.” Today’s historically low levels of trust in government across all generations point out that a diverse and broad group of people of all ages have been disenfranchised by a corrupt political apparatus.

By presenting millennials as “a problem,” the ruling elite is able to compartmentalize the issues of millions of people as those that can be solved through promises like “campus engagement,” or having a dialogue, rather than addressing why millennials have lost trust in the political process in the first place.

In another Washington Post article titled “Yes, you can blame millennials on why Hillary Clinton loss,” author Aaron Blake argues that the lack of support for Clinton from those between 18 and 29 (about 5 percent less than millennial support for Obama), is the reason why Clinton lost the 2016 presidential election.

Blake goes on to list how Clinton did even worse than Obama among young voters in states that decided the election-Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The author quotes Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager, Robby Mook, who admits Hillary lost because “where the campaign needed to win upward of 60 percent of young voters, it was able to garner something in the high 50s at the end of the day.”

Another explanation provided by Mr. Mook in the same article is that “younger voters, perhaps assuming that Clinton was going to win, migrated to third-party candidates in the final days of the race.”

This diversion is emblematic of the ways millennials are usually portrayed in the media-as respondents in surveys and variables in trends, rather than people who can organize and talk for themselves. Such articles end up justifying the failure of either political establishment through blaming “Third parties” and millennials. In doing so, their authors reveal how simplistic definitions of millennials can be used to weaponize the news and create societal divisions.

The Actual Millennial Narrative Will Not Be Televised

Last but not least, since corporations own most of our channels of information, it is unlikely that they would expose the label as an instrument for corporate propaganda. Quite the opposite, the financial industry is heavily involved in producing and promoting content about millennials.

For example, JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs use the label to their advantage by sponsoring millennial news organizations and presenting themselves as ” thought leaders” in the suspiciously market-friendly field of generational theory.

If banks and generational experts can become spokespersons for millions of millennials and, coming soon, Generation Z, then what is the role of the people behind those labels?

The label’s creation and use by the ruling class in the U.S. suggests that the actual millennials, the nearly 80 million human beings whose thoughts and opinions have been largely manufactured by the generation industry, were never meant to play a role in telling their own narrative, at least not in a way that truly represents millennials’ diversity and perspectives.

Now that millennials are getting up in age, the financiers of “insights” about them, who have in fact written and prophesied about their “identity” before many of them were born, are not going to give them the reigns to explore their own narrative. Quite the opposite—a new generation, Generation Z, is already being preemptively defined and used to continue the speculations, prophesies, and propaganda that has shaped the public’s understanding of generations according to the “insights” of the corporate state.

Corporate Media Loves “Common” Definitions of Millennials

The lack of desire to investigate the origins and reductive uses of the millennial label is illustrated by mass media’s inability to move past “common” definitions of generations. Here’s how NPR describes the origin of the label in a recent article:

It was only in the 1980s, 1990s that the word millennial started to be used to refer to the coming of the third millennium. So that was when two demographers named William Strauss and Neil Howe published a book in 1991 called Generations . And at the time, this new generation was just starting preschool, but Strauss and Howe decided that they should be called millennials, because they would be coming of age in the new millennium.

So, in 1991 two “demographers” decided to preemptively baptize millions of people before many of them were even born. I guess that explains it, then.

To be fair, every once in a while, news organizations show signs of shallow repentance for their haphazard use of the label. The NPR piece mentioned above quotes an article from The Wall Street Journal in which the latter organization recently expressed concerns about its own use of the word:

Comedian and late-night host Stephen Colbert even mocked our coverage on an episode of “The Late Show.” What we usually mean is young people, so we probably should just say that. Many of the habits and attributes of millennials are common for people in their 20s, with or without a snotty term.

Let’s also be precise when referring to this group and resist the temptation to use stereotypes, apply a blanket label or let the term become a crutch in our stories. Occasionally, we’ve referred to millennials when we really meant teenagers . Millennials, also known as Generation Y, are commonly defined as people born from about 1980–2000 . That means the oldest millennials are approaching 40 and the youngest are seniors in high school. Such explanations are worth including in articles that are centered on millennials.

Even in their attempt to investigate their own use of the label, The Wall Street Journal fails to go deeper than the common (meaning, elementary) way of defining millennials as solely “x-to-x years old.” By using a highly reductive definition of generations, corporate media outlets are able to level all of the “uncomfortable” millennial perspectives and market the ones that make the cut.

Not to be left out, BBC also joined this “high-level” investigation…only to conclude that, according to experts like Jason Dorsey, CEO of the “Center for Generational Kinetics,” we should keep using the millennial label because it is a “conversation starter.”

“Experts say it’s best to keep using the term-even if millennials are oft-painted as lazy, expectant job-hoppers who don’t have the cash for retirement plans, but do for bottomless mimosa brunches,” the article states. “It’s a name that’s been dragged through the mud. But also one that quickly communicates the particular profile of certain set of people-good and bad.”

The article mentions that Dorsey’s company “studies millennials and Generation Z.” According to their own website, the company “solves tough generational sales and marketing challenges through research” by applying their “Generational Context™ approach,” and comparing the results with their “trove of front-line knowledge.” In other words, they sell “insights” about millennials to corporations.

Unsurprisingly, the efforts of such companies end up perpetuating the same divisions they claim to counter. For example, during a TEDx talk, Jason Dorsey presented stratifications within the millennial generation as a “new controversial discovery.” According to him, the millennial generation is currently splitting into two trajectories—one path is for the millennials who were “told exactly what to do” and the other path is for those who are not creating “real world traction” for a reason “we don’t know yet.”

Like other generation experts looking to prove their credibility, Dorsey asserts that the media only concentrates on bad millennial behavior. Blaming “the media” is a great escape hatch for anyone who is trying to sell generational theory. Yet, a lot of what experts say rivals the unfounded assumptions and stereotypes perpetuated in the media.

“They are not able to hold down jobs, they are not able to own the outcomes of their lives, that’s who the news wants to talk about,” says Matt Beaudreau who works with Dorsey and does a similar routine, during which he claims that the millennial generation is splitting in two, “for reasons we don’t know yet,” and after they reach 30, millennials can no longer relate to the other side of the generation.

Beaudreau advises employers that in order to keep the attention of millennials, they need to “get a screen in front of us, and just keep going.” “As long as I am talking to the screen and you are talking to the screen,” Beaudreau says, “we will follow you all the time.”

It’s All About Controlling the Narrative, So Why Not Create Our Own?

It is important to note that the corporate hijacking of the millennial identity is not unlike other efforts to profit from, silence, and censor voices that question the status quo.

Just like the pro-union voice, the anti-war voice, the climate change voice, and other perspectives censored in the corporate media, the actual millennial voice is replaced by a reductive version of itself-it is either that of the millennial entrepreneur, the finally-warming-up-to-the-stock-market millennial, the entitled millennial, the ‘psychologically scarred’ millennial killing industries left and right, the idealistic millennial, the recently popular self-hating millennial, or whatever other non-system threatening template of behavior can be attached to the millennial “handle.”

When we let spokespersons define us and dictate what we can and cannot call ourselves, we lose our ability to tell our own stories. This is why we need independent platforms and organizations that provide ways for all millennials to take control of their narrative.

As the examples above illustrate, waiting for NPR, The Wall Street Journal, BBC, and insights-selling businesses to spark a deeper analysis of the millennial generation, or to point the public discourse to a more nuanced understanding of generations, is futile.

What is the counterweight of top-down efforts that aim to define who we are? I believe that an independent, millennial-focused platform that is genuinely open to diverse perspectives and thoughts has the power to reclaim the millennial narrative, even in the presence of an industry that actively works to simplify and manipulate our understanding of millennials.

This is why I created postmillennial, a story-sharing site that lets millennials and their allies share content without the corporate spin and lack of analysis that characterize most mainstream uses of the label. I welcome you to join our community of authors and help counter reductive narratives about the millennial generation with your perspectives and ideas.