Facebook “failed to alert users and took only limited steps to recover and secure the private information of more than 50 million individuals” (London Observer, 3/17/18).

Facebook is under fire for (among other things) its involvement with Cambridge Analytica, a British data analytics firm funded by hedge fund billionaire and major Republican party donor Robert Mercer and formerly led by President Trump’s ex–campaign manager and strategist Steve Bannon. Cambridge Analytica harvested data from over 87 million Facebook profiles (up from Facebook’s original count of 50 million) without the users’ consent, according to a report by the London Observer (3/17/18) sourced to a whistleblower who worked at Cambridge Analytica until 2014.

The users’ personal data was gathered through a survey app created by a Cambridge Analytica–associated academic named Aleksandr Kogan, who used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk micro-work platform and Qualtrics survey platform to gather and pay over 240,000 survey-takers. The data collected was then used by Cambridge Analytica to comb through the political preferences of the survey takers and their Facebook friends, without their knowledge, to create individual “psychographic models” that would then allow for entities (like the Trump presidential campaign) to target them with personalized political advertisements and news.

Worse than the breach itself, Facebook apparently knew about this data-harvesting for years, and in fact, according to another whistleblower who worked at the social media giant itself (Guardian, 3/20/18), had a policy of allowing developers to gather user data by linking apps with Facebook logins, as Cambridge Analytica did through its partnership with Kogan and his survey app. While Facebook changed its terms of service in 2015 to prevent this, the company maintains that it is not at fault for the breach. Still, Facebook failed to report the breach to their users, and then threatened to sue the Guardian (owners of the Observer) upon publication of the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower’s testimony.

Facebook also recently suspended New York–based analytics firm CubeYou from their platform for using similar data-harvesting tactics for targeted advertising under the guise of academic study, which Kogan has described as common practice in the ad industry.

The use of consumer data harvested through Facebook and other online platforms for micro-targeted political content has raised questions about privacy and the potential for abuse, particularly in regard to the proliferation of so-called “fake news” in the run-up to the Brexit vote and the 2016 US presidential election; the involvement of Trump adviser Steve Bannon and billionaire Trump backer Robert Mercer in Cambridge Analytica only heightens those concerns. In response to the Cambridge Analytica fiasco, the British Information Commissioner’s Office is now inquiring into whether Facebook violated the country’s privacy standards

The Data Duopoly and the Media Oligopoly

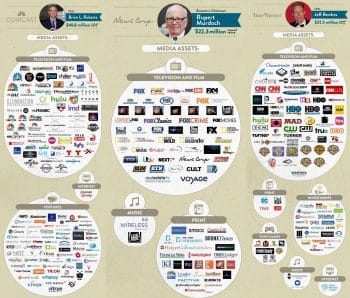

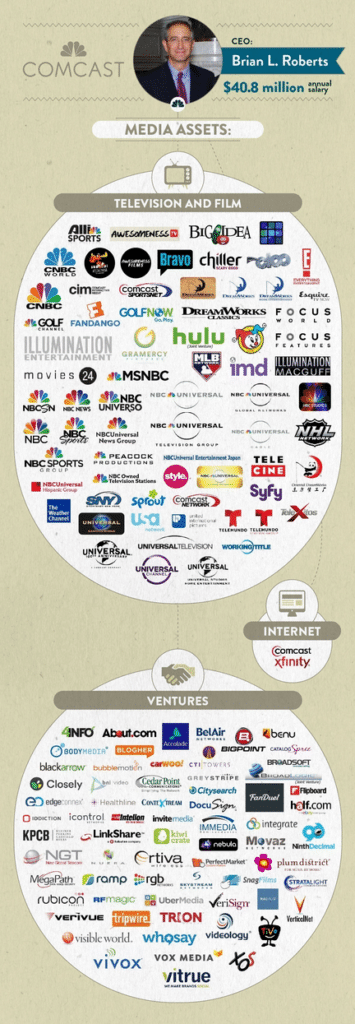

Comcast‘s media assets—from “The Six Companies That Own (Almost) All Media” (WebpageFX)

Fueling the scandal is Facebook’s dominant position in advertising, the source of almost all of the company’s $40 billion in annual revenue. Alphabet, the parent company of Google (whose ad revenue totals over $74 billion annually), and Facebook arguably maintain a duopoly over digital advertising. Together, the two internet giants account for just under 60 percent of all non-China digital ad revenues in the world in 2017, according to eMarketer, a digital research firm. Similarly, the two companies are also responsible for 70 percent of referral traffic for web publishers.

The consolidation of social media, web search and internet platforms among just a few players is central to this dominance in advertising: Facebook also owns the popular messaging app WhatsApp and the photo-sharing service Instagram, while Google owns the massive video platform YouTube.

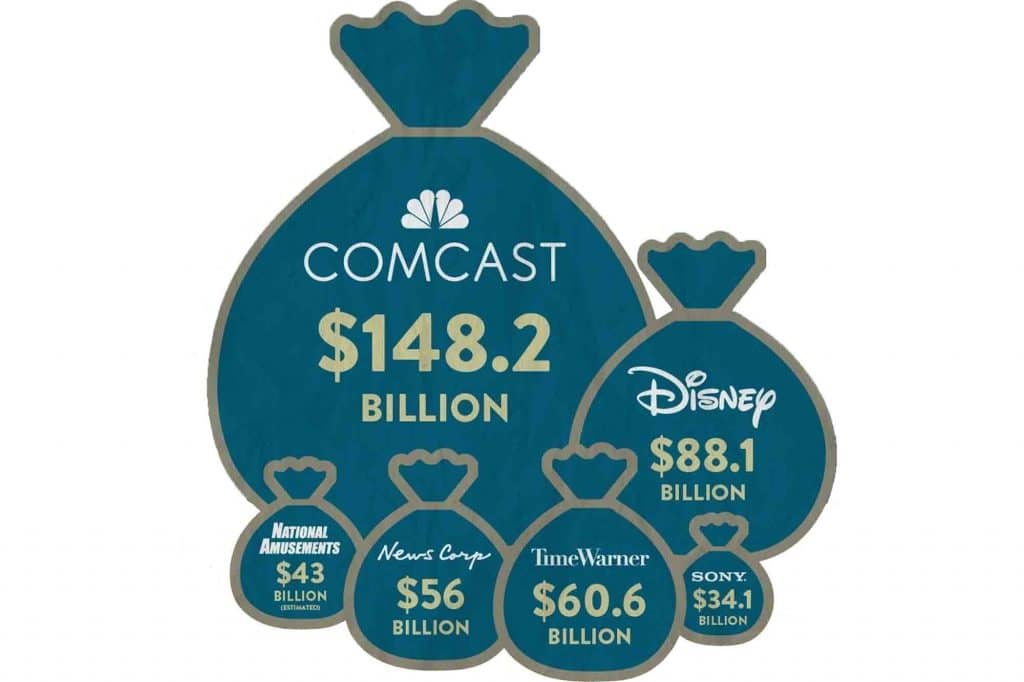

Waves of consolidation in the technology, telecom and entertainment industries have concentrated power over media content and delivery into just a handful of companies. Today, there are only a few dominant players in each industry:

- Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft rule the social media, search, e-commerce and digital advertising domains.

- Comcast, Verizon, Charter and AT&T are the only internet service providers in most locations throughout the US, and often don’tcompete with one another in specific regions and cities.

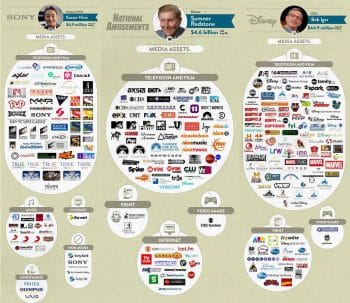

- Comcast, the Walt Disney Company (which recently acquired 21st Century Fox), News Corp, Time Warner and National Amusements (owner of CBS and Viacom) have conglomerated the majority of US media and entertainment properties.

While these companies have vertically integrated themselves to staggering degrees in their industries, what’s worse is the increasing pace at which they have sought to consolidate horizontally across sectors. Social media, internet and phone service providers, newspapers, television, radio, sports, magazines, book publishers and streaming services are all increasingly intertwined below just a few owners, creating conflicts of interest in pricing and providing content.

It is no wonder that a news station like MSNBC, owned by the cable giant Comcast, would be reluctant to take on antitrust regulation or adjacent issues like net neutrality on its shows. Or why the Washington Post, owned by Amazon CEO (and world’s richest billionaire) Jeff Bezos, publishes puff pieces on the supposed benefits Amazon’s new headquarters could provide to potential locations.

Giving a Green Light

The consolidation in these industries results from the green light given to mergers and acquisitions by recent presidential administrations, who are supposed to maintain oversight of anti-competitive practices through the antitrust divisions of the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission.

A casual observer might think the Trump administration has broken this trend and taken a hard line against corporate consolidation. AT&T’s bid to merge with Time Warner was blocked by the Justice Department on the grounds that AT&T, an internet service provider, could choose to favor media content owned by Time Warner—like its properties CNN, TNT and HBO—over that of its competitors, and ultimately increase prices for consumers.

But when then-candidate Donald Trump vowed on the campaign trail to block the merger, he explicitly linked it to CNN’s negative coverage of himself: “They’re trying desperately to suppress my vote and the voice of the American people,” he told supporters (Reuters, 10/22/16):

As an example of the power structure I’m fighting, AT&T is buying Time Warner and thus CNN, a deal we will not approve in my administration because it’s too much concentration of power in the hands of too few.

Trump’s overt, ongoing hostility toward CNN complicates the DoJ’s case against the merger, as the prospect of a president ordering antitrust action against a media company because he objects to the way it covers him raises serious First Amendment alarms. AT&T and Time Warner have taken legal action against the DoJ, maintaining that the merger would allow them to better compete with large tech conglomerates like Facebook, Amazon and Google, who are increasingly creating their own media content.

In the same campaign speech (The Hill, 10/22/16), Trump singled out the owners of two other frequent targets of his wrath, NBC and the Washington Post:

Comcast‘s purchase of NBC concentrates far too much power in one massive entity that is trying to tell the voters what to think and what to do. Deals like this destroy democracy….

Likewise Amazon, which through its ownership controls the Washington Post, should be paying massive taxes but its not paying, and it’s a very unfair playing field.

Trump has continued a crusade against Amazon for its favorable contracts with the US postal service. But even as Trump raises concerns about concentration by particular media companies that have raised his ire, in practice he’s been generally very tolerant of corporate consolidation: In its first year, his administration allowed a hefty $1.2 trillion worth of mergers and acquisitions, the most of any president’s first year. His FCC has facilitated the continued consolidation of the majority of local television and radio affiliates under Sinclair Broadcasting (FAIR.org, 5/8/17), a conservative media conglomerate with closeties to the Trump administration that has been steadily increasing its share of local media markets since 2004.

Unfortunately, the Obama administration’s record on antitrust doesn’t look much different. While Obama did block some consolidation efforts, including the mergers of AT&T and T-Mobile, as well as that of Comcast and Time Warner, many large media and technology mergers and acquisitions during the Obama years have resulted in corporate behemoths with the power to stifle innovation, discourage competition and increase prices. These mergers and acquisitions include Comcast and NBC Universal, AT&T and DirecTV, Charter and Time Warner Cable, Facebook and Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp, Microsoft and LinkedIn, and Live Nation and Ticketmaster, among many others.

One sign of a dysfunctional antitrust system is the revolving door for agency heads, civil servants and government officials who go to work for companies that they formerly regulated (or failed to regulate), either working for them directly or working for the large private law firms that represent them. An egregious example is Obama’s first DoJ antitrust chief, Christine Varney, who now works for Cravath, Swaine & Moore, the law firm representing Time Warner in the AT&T merger lawsuit. (United Airlines, whose merger with Continental was approved during Varney’s tenure, is another Cravath client.) Obama’s last DoJ antitrust chief, Renata Hesse, now at the New York law firm Sullivan & Cromwell, was a lead advisor for Amazon in its takeover of Whole Foods.

Perhaps the most damning case is Obama’s FTC chair Jon Leibowitz, who was criticized for his agency’s leniency towards Google—a company on intimate terms with the Obama White House. Leibowitz and his fellow FTC commissioners rejected staff recommendations for antitrust action against the search giant. Leibowitz’s new employer, New York law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell, lists Google among its clients. Leibowitz is also the chair of the 21st Century Privacy Coalition, a trade group funded by Comcast, AT&T and Verizon that backed a successful Republican effort to overturn Obama-era FTC privacy regulations, winning the ability to share customers’ data without their permission.

Combating Corporate Concentration

Clearly, the impact of the revolving door between government agencies and Big Law is a problem in regulating antitrust. However, US antitrust laws and enforcement themselves are often insufficient in tackling the issues central to consolidation in technology and media. Antitrust policy since the late 1970s has generally focused on the short-term interests of consumers—meaning low prices—at the expense of the overall health of market sectors and long-term consumer protection, according to Lina Khan, director of legal policy at the Open Markets Institute. (The anti-monopoly institute was housed at the New America Foundation until complaints by Eric Schmidt, the former executive chair of Google and a large donor to the Foundation, prompted a severing of ties.)

Of course, with web companies like Facebook or Google, the fundamental maxim for ad-based platforms still holds: if it’s free, you are the product. Advertisers are indeed the true customers in this business model. With no “costs” to consumers in a dollar sense, measuring the pitfalls of consolidation by looking at prices available to consumers is inadequate for determining whether a company like Google or Facebook should be regulated for antitrust reasons.

Companies like Amazon pose a similar threat to long-term economic health. Amazon’s strategy of accruing market share in the cloud computing and e-commerce sectors through aggressive business tactics and investment (not to mention massive government contracts), rather than pursuit of quarterly profit, actually lowers prices on goods for most consumers, but at the same time destroys brick-and-mortar retail stores and limits overall consumer choice in the long run. Similarly, the shift towards an all-online economy, with infrastructure largely controlled by Amazon, contributes to huge job losses and depresses wages.

Amazon, Facebook and Google, along with other internet and media companies that have cross-sector investments, like Comcast or AT&T, reap their gains from network effects, meaning that the ease of availability and usability of their platforms locks customers into using that company’s other products, while giving them the opportunity to engage in predatory pricing against other competitors to drive them out of businesses.

This is especially damaging with cross-sector consolidation. For example, if you are an Amazon Prime subscriber, and have a choice between shopping at Whole Foods, where you can get discounts for being a Prime member, or some other grocery store without the same perks, you will likely choose Whole Foods for the lower prices. However, these low prices have the potential to price other grocery stores out of the market, consolidating the market further and decreasing consumer choice and competition.

The same goes for social media like Facebook and Google for search engines, whose market dominance leads to control of smaller platforms like Instagram, WhatsApp and YouTube, and ultimately creates behemoths with power over consumer data that is hard to challenge, because they make their platforms so convenient and universal. After all, the major benefits of a social network like Facebook is having all your friends in one place, while having a video platform like YouTube with the highest possible amount of videos seems to make sense.

“Unlike a traditional monopoly whose power stems from its control over the production and pricing of a single good, a platform draws its power from its position as a kind of middleman, a broker that controls the relationship with producers and consumers alike,” argues K. Sabeel Rahman (Boston Review, 5/4/15).

One remedy would be stricter enforcement of privacy and data protections in Facebook and Google’s terms of service, and making these protections clear to consumers so that they know their rights. Paying consumers for their data could also be a useful solution, as internet activist Tim Wu (New Yorker, 8/14/15) has suggested. Open Markets director Barry Lynn and fellow Matthew Stoller (Guardian, 3/22/18) have advocated for spinning off Facebook’s ad network, in addition to calling for strict fines against executives if the company is found to have knowingly violated a 2011 FTC consent decree that stipulated that Facebook not share its users’ data to third parties without permission.

Another strategy could be treating the companies that handle massive amounts of data, particularly internet and digital advertising giants like Facebook and Google, as public utilities, which Big Tech has long been fearful of. After all, it is hard to live and work in our society these days without using search engines or social media. This strategy would recognize the monopoly that Facebook and Google (as well as Amazon and internet service providers like Comcast or AT&T) have in their respective sectors, but would entrench and enforce policies of non-discrimination against outside platforms and content and would limit the potential for rate-setting. However, calls for regulating consumer credit reporting company Equifax as a public utility after its massive 2017 data breach have not yet materialized.

Most importantly, the forest must not be missed for the trees: the fight over data protection and privacy must not obscure the importance of stronger antitrust regulation. New mergers and acquisitions should be scrutinized more harshly than they have in past presidential administrations. Past cross-sector mergers and acquisitions, especially in media, should be reviewed and potentially rolled back.

Turning the Tables on Tech

It seems as though the tide is beginning to turn against Big Tech consolidation. The European Union has taken an aggressive stance against the monopoly power of Facebook and Google and their policies on the protection (or lack thereof) of the data of its users.

For example, Facebook’s data practices, such as default privacy settings that automatically revealed users’ locations, were ruled illegal in Germany in February. Spain’s data protection agency fined Facebook €1.2 million over such policies, which also involved the collection and sale of data on personal beliefs without notifying users. France fined the company its data regulation agency’s maximum of €150,000 last May for compiling data from non-users without their consent for targeted advertising using third-party website cookies and plug-ins. Fines and legal proceedings against Facebook over its data collection and privacy policies have been taken up by Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium as well. The European Commission also fined Facebook €110 million—about 0.3 percent of the company’s 2017 revenues—for misleading regulators during its acquisition of WhatsApp.

The European Union has rolled out a new law on handling data, the General Data Protection Regulation, that will go into effect on May 25, 2018. The law will have far-reaching effects on Facebook and other data-centric companies like Google, particularly in maintaining user consent for data collection, and will come with harsh penalties for violation: Fines can amount to 4 percent of a company’s annual global revenue. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has not yet committed to applying European privacy laws to the company’s privacy policy outside of the EU.

Google has also come under fire in the EU, and is currently under investigation by the European Commission over the way its Android mobile operating system (a clear monopoly, with 80 percent of the European mobile market) automatically pre-installs Google apps. Additionally, the EU has fined Google €2.4 billion—about 2.7 percent of 2017 revenues—for using its search engine monopoly to give preferential treatment to its Google Shopping service.

In the U.S., signs of life are appearing as well, partially because the Cambridge Analytica scandal galvanized opposition to Facebook. Politicians in both parties have begun to speak out in favor of stricter antitrust regulation. The FTC has opened an investigation into Facebook over its privacy practices, while Zuckerberg is set to testify April 10 before the Senate Judiciary and Commerce Committees. Zuckerberg is also set to testify before the House Energy and Commerce Committee on April 11, and has released his testimony.

Still, the fight against the lack of data protection and privacy and the continued consolidation in tech and media will be a tough one: Facebook is reportedly beefing up its lobbying efforts in DC, and is currently lobbying against privacy laws in California and Illinois. Additionally, many top Democrats have close ties with large tech companies. For the Democratic Party, safeguarding the sanctity of privacy and choice would mean breaking with these powerful allies in tech and media.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal has shown, once again, that these large tech and media companies cannot be trusted to police themselves. In order to win the battle over data protection and privacy, individuals will need to demand that the social media, search, technology and media platforms that we use and consume every day, and which constitute such an oversized part of our culture and social interactions, are regulated with greater zeal than has been applied in recent decades.