Ankica Čakardić is an assistant professor and the chair of Social Philosophy and Philosophy of Gender at the Faculty for Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. Her research interest include Social Philosophy, Marxism, Marxist-feminist and Luxemburgian critique of political economy, and history of women’s struggles in Yugoslavia. She is a member of The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg Editorial Board. Currently she is finishing her book on the social history of capitalism and Marxist critique of Hobbes and Locke.

Darko Vujica, Prometej.ba: You often stress that the problem of gender inequality cannot be solved within capitalism. I would like to talk about the relationship between gender and class and production relations in capitalism that reproduce gender inequality. It is obvious that women in capitalism, despite their gender quotas and legal equivalence (where they exist), remain in a subordinate position. What are the mechanisms in capitalism that enable further reproduction of gender inequalities?

Ankica Čakardić: Inequalities are immanent to capitalism. Capitalist modes of production are maintained through the reproduction of inequalities. In a concise form we can say that social relations of capitalism are being realised due to simultaneous exploitation processes (usually understood through the class category) and oppression (understood through the category of gender, race or sexuality). These processes that systematically generate inequalities allow the reproduction of class relations and labor power, not as separate phenomena, but unitarily, thus forming capitalist system as a whole. The basic mechanisms of gender inequality, historically and theoretically, feminists explain in different ways–radical feminism focuses on the problem of male domination, liberal on unequal opportunities for individual advancement, and Marxist and socialist feminists on the tension between productive and reproductive labour and their relation. Not only do these feminist currents differ in their interpretations of the origins of gender oppression (radical feminists will rather say “sexual” oppression, which is problematic for a number of reasons) but also in the goals and ways of combating it. Gender quotas and other liberal legal instruments, as criticised by Marxist feminism, remain at the level of an empty gesture, if at the same time they do not undermine the class relationship that defines, determines and limits them.

DV: You mentioned unpaid reproductive labour. How does profit accumulate through unpaid reproductive work?

AČ: The problem of domestic labour began to be analysed more systematically in the 1970s, as part of the Domestic Labor Debate, setting the basic coordinates for the feminist theory of social reproduction. Feminists were caught up with Marx’s labour theory of value and insisted on the thesis that any work that produces surplus value necessarily depends on unpaid, “invisible”, domestic labour. Not only did they engage in epistemological broadening of Marx’s fundamental categories from Capital such as labour or value but they also organised campaigns, like Wages for Housework, that sought to redefine the Marxist concept of labour. They argued that labour is not only present in the production but also in homes. Cooking, breastfeeding, ironing, giving birth, sex, all this is unpaid accumulated work, they believed. Already during the 1980s, two theoretical currents dealing with the problem of social reproduction appeared in the framework of feminism. I wrote on this subject previously. One tradition is “dual-systems” theory (e.g. Silvia Federici, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati), which argues that domestic labour produces surplus value, just like every other labour, and the other tradition is “unitary” (e.g. Lise Vogel, Tithi Bhattacharya, Cinzia Arruzza, Sara Farris), which claims that domestic labour does not produce exchange value, but only use value. In other words, unitary concept argues, and rightfully so, housework is necessary for every accumulation of profit but does not in itself produce surplus value.

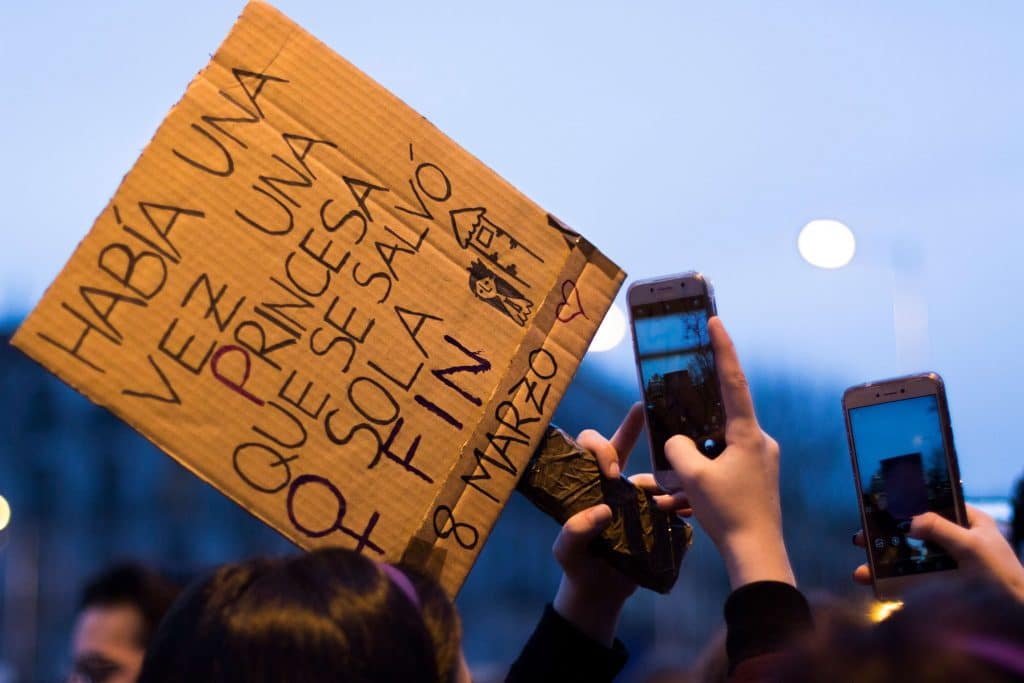

DV: Lately we see more frequent feminist mobilisations; as the best example, we can mention the Women’s March in the United States, which also encouraged demonstrations in other (southern) U.S. and European countries. Reproduction of misogyny, triggered by neoliberal capitalist dynamics, obviously confronted the resistance of women. Cinzia Arruzza says that in some countries (Argentina, Spain, Italy) it is difficult to differentiate feminist struggle from the working class today. It seems that feminist movements open up new political horizons.

AČ: Feminists in Spain have just arranged another huge march for the 8th of March, Italian and German feminists, same as in UK, are preparing similar actions, women in Brazil are organising a mass anti-fascist demonstration at the moment, women in Argentina are preparing for a massive rights strike for the 8th of March, women in USA have been leading a militant wave of teacher’s strikes, victory of women in Ireland over the abortion law is huge, #MeToo campaign is still ongoing and hopefully will get more militant, we can learn a lot from Poland and their recent women’s strikes, and the 8th of March in Zagreb is growing significantly year after year. The feminist movement is evidently growing, we need to continue to steer it more to the left and it is precisely in the feminist movement that the foundations for future progressive international struggles should be found. One who does not see this clearly is blind.

The wave of women’s protests and strikes around the world is fantastic. It seems to me that the most important thing in all these great feminist protests is that they successfully combine anti-neoliberal struggle both in households and workplaces. Since it is a matter of a whole series of labor and social demands that simultaneously include the struggle for reproductive justice and better working conditions, it is difficult to detach the initial feminist spark from these protests from the class struggle. As always in the history of major crises, women’s organisations are mobilising the widest masses of people. Times are getting darker, which is why we must not underestimate the political value of these feminist resistances. Women’s strikes and protests are indeed a brighter part of our recent militant history.

DV: Revolution must be feminist, or it will not be?

AČ: Exactly! When feminism is revolutionary, it does not focus itself on a separate part of the system; it rather aims to grasp the totality of capitalist social relations. At the same time, the struggle must take place in our workplaces where we persistently insist on feminist demands, just as in the context of feminist struggles where we have to continuously relate gender and class. Only in this way can we speak about the meaningfulness of anti-capitalist resistance that is sustainable and unitary, and not simply the sum of different intersections or parallel structures or NGO platforms that only nominally overlap without universal political logic.

DV: Likewise, I would like to talk about sexism on the left. Many leftist parties and organisations still retain sexist patterns of behaviour. Can you talk more about it in more detail? How is this sexist language on the left (re) produced?

AČ: “Still,” you say? It’s a tough and a bit anxious topic for every leftist feminist. I would point out a few things here, but beyond the “poststructuralist mood”, so to say, because language here seems to me only as a consequence of social and historical causes.

History and empirical data persistently demonstrate that the left is not immune to sexism, nor to machismo nor misogyny. On the left, we still have too many all-male panels, journals edited mainly by men, men asking questions and giving comments from the audience, a theory written mostly by men, men who persistently patronise women. Women are generally invited to talk about feminist topics but when the subjects include e.g. economics, Marxist theory, history or general political analysis, women are chronically few here. On the other hand, when something needs to be translated, someone contacted, e-mailed, coordinated, networked, then we have more women involved. Obviously, the gender quotas are important for the left also but as an inclusion mechanism they make sense only if we work daily on empowering female and non-binary comrades/colleagues/analysts/theoreticians in different fields of theory and practice.

Sve su to vještice, Facebook. Jean-Paul Sartre “saying” to Simone de Beauvoir- You should have thought with my head.

Feminism is very sensitive to sexist behaviour, and rightfully so, so it strikes back. But sometimes in a rather nonconstructive way, in the moralising tone of radical feminism, finding all the causes of the evil of this world in men. This is very dangerous and it does not reflect the totality of the problem. Gender and class cannot be separated, they are persistently defined and conditioned. One of the examples of such a dangerous retreat is the transphobia of radical feminists who are convinced that biology is the basis and end of all feminism. This conservative biological fetishism that excludes trans women from feminist movements because they are not “women” is wrong both theoretically and politically. This is best illustrated by the fact that the ahistorical radical-feminist mystification and ontology of the sex as an eternal being, with its made up biological differences and constant binary antagonism of the sexes, is getting closer to the right-wing pseudo-argumentation of the exclusion of transgender people. That is really dangerous.

In addition to what was just mentioned we also have a situation in which feminism is often limited in leftist NGOs if it is explicitly socialist. That is how feminism is being pacified in left organisations and parties in general. The fight against sexism and violence has to be carried out by all progressive organisations; need for self-defence should not be neglected, as well as enabling conversations, infrastructures, reading groups, classrooms, discussions, writings, analyses, education on feminist topics which have to be included as basic principles in the practice of leftist organisations. We must be able to understand how the world works in order to be able to change it. I know, it is a lot of painstaking work, but–history has proven–if there is going to be a real emancipatory change, it will happen first on the left, nowhere else.

DV: Bifo Berardi said that the social dynamics that led Hitler to power brought Trump today. But Trump and the USA are not an isolated case. We in Europe know this very well. Perhaps fascism is not a social system in which we live, but it is obvious that after a long time there are again the right-wing political forces mobilised by an increasing number of people.

AČ: Far from the fact that history did not open a new page with Trump. But at a more general level, I think it is very important to be careful with the comparisons of Hitler and Trump, or the forces that led them to power. For example, I do not think that Trump can be called a fascist, although his policy is highly conservative, xenophobic, soaked with post-truth manipulation, and alike. Populist ideology should not be identified with fascism. In addition, there is a whole series of historical specificities of fascism that in no way are the same as in the case of Trump. It is not just a matter of academic or analytical precision we are dealing with here but the need to calm a somewhat justified concern about Trump so that we do not slip into politics of lesser-evilism.

In spite of the fact that Trump increasingly empowers ultra-right wing forces, including racist, misogynist, transphobic and anti-Semitic policies, it should be noted that American politics ensured quite years ago (at least from Reagan, via Bush, to Obama) a smooth and long-term development of reactionary right-wing forces. It is with the consequences of the horrors of these politics that we are facing today. If we talk about fascism today, then probably our subject should be Jair Bolsonaro.

Clara Zetkin stated in 1923 that fascism is deeply rooted in economic crisis of capitalism and in the proletarisation of broad petty-bourgeois classes. In order to address the problems of the economic and social crisis, fascism systematically destroys democratic institutions and physically attacks workers’ and leftist’s organisations. It aims to shift the blame for crisis away from capitalism, looking instead for scapegoats such as migrants, LGBTQ people, women, people of colour, communists, Muslims, Jews, etc. I think that fascism must not be lowered analytically to the level of ideology–which is undoubtedly important–but instead to seek the roots of fascism and crises in social relations, therefore, capitalism.

And the role of women in right-wing movements is a phenomenon worthy of analysis. I have recently written about feminism and the alt-right where I tried to open up the subject of the link between feminism, neoliberalism and the extreme right.

DV: I can agree with your analysis, but when we talk about Trump and other alt-right forces that exist in Europe, I remember Fukuyama’s comment, saying that Trump would be replaced by somebody else in the next elections (I suppose that alluded to centrist-oriented Democratic Party candidates) and things will stabilize. However, what are the implications of the complete political field of choice of types such as Trump, Orban and the like? Let’s take a look at what’s happening in Italy, AfD almost overtook SPD in Germany, and so on. I’m afraid the political spectrum has moved so far right and that it will move even further to the right. The result is that we now have a policy of lesser-evilism as the main alternatives and figures such as Macron, Hillary Clinton, etc. are posited as the pegs of defense against the far right. This blackmail is a huge problem.

AČ: I absolutely agree that it is a blackmail. The breakdown of social democracy and the withdrawal of the left towards the center, the tactical renaming of politics into “platformism”, the deeper drop in class politics and the adherence to conservative economic policies, are all the processes that contribute to the strengthening of the right. And when a certain left-wing position does not want to be a part of the politics of lesser evilism, it is automatically discredited as anachronistic and naïve.

With the economic crisis, there is a growing social crisis. Right-wing and ultraconservative movements recognise the social crisis and in response to it create incredibly obscure and conspiratorial theories. And, instead of locating the crises in capitalist political economy, they blame different minorities. As the social crisis deepens, we will have to work on two fronts. In the short term, we need to fight–sometimes illegally–for the preservation of already gained social and material rights that are being abolished every day. In the long term, we will need to gradually, stubbornly and devotedly build a progressive and ecologically sustainable political future. The assumption for the latter is not just a self-explanatory “unification” of different groups, parties, initiatives, as if that ensures any kind of political unity. Rather, the basic assumption of a united front is to primarily conceive of a coherent and serious progressive politics for the left to finally have the opportunity to build a movement that will have a real emancipatory character.

DV: Walter Benjamin once said that every rise of fascism was an expression of an unsuccessful revolution. Is that not lazy and impotent (primarily third-degree) social democracy with its (new) liberal policies embarrassed by the alt-right movements? Recall Margaret Thatcher’s statement that her greatest political success was Tony Blair.

AČ: Fascism is not successful thanks to the impeccable right-wing organisation or simply the failure of the left. Fascism carries, articulates, builds and empowers the liberal middle class. In times of economic crisis liberals move their centrist agenda to the right, retain all their strengths in their power, pacify resistance and attack every criticism of capitalism because it seems for them inappropriate, rough and meaningless. Redirecting politics from the class struggle mainly to the pluralism of liberal-identity issues (which we have generally witnessed since the 1980s) is used to suppress the left. Alternatives to capitalist and fascist tendencies of society have to be sought both in theory and practice–in writing and education and research, just like in the streets, kitchens, prisons, bedrooms and work places. Anti-fascism was once effective, it will be again.

DV: The current level of workers’ rights, women’s rights, racial equality and other rights that citizenship in capital-parliamentary democracies has, has been selected through history as a result of intense national struggles; protest, strikes, and other forms of disobedience, not through institutions that have always pacified class struggles. Allow me to be skeptical about the possibility that capitalism can be replaced by (socialism) without violence.

AČ: I think the constant pressure on political establishment is inevitable in every tactic of progressive resistance–whether on the streets or as a critique of mainstream media and theory. But when continuity is absent, we are reacting situationally and defensively. In these moments it is most important to avoid ideas and practices of individual violence and to be organised and grouped in the fight against all forms of violence. What I am concerned about is how to respond when extreme right and alt-right movements or organised individuals are physically attacking minorities? Should we insist on “polite conversation” with fascists or listen to Clara Zetkin’s advice “Meet violence with violence”? Should we just ignore fascists figures and believe they will go away or follow Rosa Luxemburg’s “Thumbs on the eyeballs and knee in the chest!”