José Martí and Simón Bolívar, two of Latin America’s most respected independence fighters, recognized nearly a century ago that their homelands would never be free of imperial domination, until Latin America came together in solidarity as a united force.

Martí and Bolívar’s insights remain relevant in the age of neo-liberal globalization. The colonizers of their centuries have been replaced by multinational corporations and imperial states with the ability to blow up the world many times over, terrorizing the global populace. Their collective power is augmented by seemingly untouchable supranational bodies (i.e. the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization) that allow them to come together to devise the most effective ways to control the world and amass wealth.

Martí and Bolívar would be delighted to see the unique partnership that has developed between Cuba and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela — the relationship that defies the logic of neo-liberalism and takes an important step toward Latin American unity. Cuba and Venezuela demonstrate — to a world where all are forced into a “race to the bottom” — that empowering the poorest people through a needs-based partnership is not only possible but also desirable. Their mutual-aid exchanges in educational materials, medical services, and preferential prices of oil are a living counter-example to the competitive and exploitative nature of “free trade.”

In the Lands of Martí and Bolívar

For many decades, the Cuban Revolution has played a distinct role throughout the South as an openly anti-imperialist country interested in relationships built on solidarity, actively pushing for a more humane economic and social system. A poor island with little material resources, hobbled by the US imposed blockade, Cuba nonetheless offers the world medical expertise and humanitarian support. Just as the Cuban Revolution has brought food, housing, literacy and education, free and quality medical assistance to all Cubans, it has, when possible, actively supported countries and movements that share similar goals of social equity and economic justice.

The rise of the Bolivarian revolutionary movement to power in 1998, through the election of Hugo Chávez, has meant real change for the poor of Venezuela and the initiation of a new relationship with Cuba. Reinvigorating the vision of Martí and Bolívar — while respecting each other’s differing systems and different paths toward revolution — Cuba and Venezuela have built a relationship based on humanism, solidarity, mutual aid, and a shared vision of a world without poverty and imperialism. The aid that Cuba has provided is most notable in the social sphere. Cuba, rich in human capital and revolutionary experience, is aiding Venezuela as it goes down its own revolutionary path, with its Bolivarian projects and missions.

Literacy and Healthcare without Borders

The Cuban Revolution has inspired two of the Bolivarian Revolution’s largest accomplishments. The socialization of education and health was an important focus for Cuba; similarly, education and health initiatives are at the core of the Bolivarian project today.

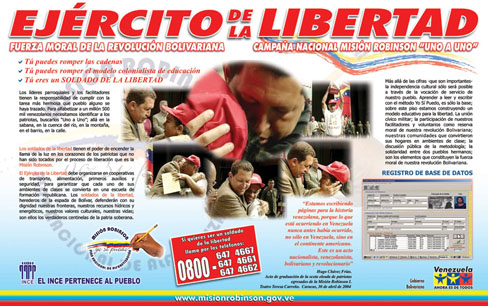

Venezuela, with assistance from Cuba, set out to devise a literacy program modeled after the 1961 Cuban Literacy Campaign, to help 1.5 million Venezuelans overcome their illiteracy.1 In Cuba, students, armed with pencils and paper, traveled throughout the island teaching reading and writing. Misión Robinson, Venezuela’s literacy campaign, employs a video literacy program, which was made by Cuba.2 Cuba donated thousands of educational videos along with TV and VCR sets, printed material for classroom use, reading glasses, and aids to train Venezuelan teachers. Venezuela has adopted these tools and translated the video into different indigenous languages. This tremendous joint effort has eradicated illiteracy in Venezuela.3

Accessible and affordable education and healthcare are essential pieces of the Bolivarian and Cuban Revolutions. In addition to Cuba’s aid in Misión Robinson, Cuba’s support has been vital for Venezuela’s Barrio Adentro (Inside the Neighborhood), a program that brings medical assistance to the poor. Over 20,000 Cuban doctors have participated in the program to date. First, doctors lived in people’s homes, but they are now working out of offices, providing free basic and preventative health care in the poorest neighborhoods of Venezuela. They provide care for seventeen million Venezuelans, nearly two-thirds of the population, many of whom have never before received healthcare. It is not solely the medical expertise but also the experience of working within a system that prioritizes healthcare that allows the Cuban doctors to aid in the Bolivarian Revolution’s first healthcare initiatives. The doctors live in the communities they serve and are on call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Clinics are stocked with equipment and medicines from Cuba. Additionally, Cuban health specialists have joined the effort to teach about health, diet, and exercise, focusing on preventative care and healthy living.4

In order to fully staff and expand Barrio Adentro and meet all the medical needs of the population, Venezuela is also training doctors. Many Venezuelans are learning medicine through education Missions within Venezuela. Thousands more are receiving free education in Cuba, attending the Latin American School of Medicine in Havana; upon their return, they will be integrated into the Barrio Adentro program.5

Oil, Trade, and Solidarity

The relationship between Venezuela and Cuba has also shown that the same values of humanism and solidarity can effectively be applied to trade.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Block, between 1989 and 1991, and the addition of extraterritorial stipulations to the U.S. blockade, threw the Cuban economy into deep crisis, resulting in the implementation of the “Special Period,” a literal economy of desperation, survival, and scarcity. Although Cuba had officially recovered from its economic depression, increased trade with Venezuela has been a relief. Venezuela has become Cuba’s top trading partner, providing oil, food, and construction materials at preferential prices.6 This assistance is essential to the maintenance of Cuba’s social system achieved by the revolution.

Defying the neo-liberal dogma of “free market,” whereby a country uses its “comparative advantage” to exploit its trading partners, Cuba and Venezuela have committed to oil accords and to a system of bartering. Venezuela has agreed to sell oil at a preferential rate to Cuba, so that, despite rising oil prices in the world market, Cuba can buy oil below the market price. Moreover, the two nations have been bartering, Venezuela’s oil for Cuba’s medicine and technical services in the agricultural, tourist, and sports industry, demonstrating a humanistic approach to trade which values health and sustainability as important resources.7

Cuba and Venezuela are constructing a trade relationship that transcends the logic of markets and profits. In effect, the two nations exchange goods and services based on each other’s needs and capabilities. This fosters an economic partnership that views the goods and resources of one nation as potential tools for aiding the other’s revolutionary processes. The larger effect of the mutual-aid exchange model is the demonstration of an efficient alternative to market-driven “free trade,” offering a vision for Latin American unity and integration that is radically different from the dominant neo-liberal model.

Towards a United Latin America

In 2002, Fidel Castro made a statement that captures the essence of the distinctive Cuban-Venezuelan relationship: “We share a mutual awareness of the need to unite the Latin American and Caribbean nations and to struggle for a world economic order that brings more justice to all people.” Revitalizing the ideals of José Martí and Simón Bolívar for a united Latin America, Cuba and Venezuela have together taken steps to eventually make it a reality.8

One such example toward a cooperative integration is exhibited through Misión Milagro (Mission Miracle), a hemisphere-wide program dedicated to providing eye surgery to the poor, free of charge. Venezuela provides the air travel to Cuba, and Cuban doctors perform the operation — a truly internationalist initiative. Thousands have already participated in this hemispheric program, and Misión Milagro will assist hundreds of thousands more.9

One such example toward a cooperative integration is exhibited through Misión Milagro (Mission Miracle), a hemisphere-wide program dedicated to providing eye surgery to the poor, free of charge. Venezuela provides the air travel to Cuba, and Cuban doctors perform the operation — a truly internationalist initiative. Thousands have already participated in this hemispheric program, and Misión Milagro will assist hundreds of thousands more.9

Cuba and Venezuela have also collaborated with Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina to create the first Latin American joint venture satellite television station, TeleSur (Television from the South). The station is designed to be an alternative to CNN, providing voices and viewpoints from the South. TeleSur broadcasts international news and specializes in independent documentaries made in Latin America, promoting both political and artistic Latin American perspectives.

Two further projects for Latin American integration are PetroAmerica and the more encompassing Alternativa Bolivariana para las Americas (ALBA), a counter proposal to the US-backed ALCA (Free Trade Area of the Americas).

PetroAmerica would seek to consolidate the energy resources such as oil, natural gas, and electricity of Latin America guaranteeing Latin American nations all of their energy needs. Moreover, PetroAmerica would enable the participant nations to use their natural resources for their collective benefit, effectively curtailing the ability of foreign capital to export the energy profits away from Latin America and into the Global North.

ALBA’s goal is the grandest of all: to integrate the economies of Latin American based on the principles and methods of Cuba-Venezuelan mutual aid, planning trade based on the values of humanism, solidarity, and self-determination, according to needs and capabilities of the participant nations.10 Contrast to the Social Darwinist policy of ALCA — according to which profits are the sole arbiter of success, taking precedence over the elimination of poverty and the overall development of poor nations — cannot be clearer.

Limitations

Although Cuba and Venezuela are nurturing the vision of Martí and Bolívar, they face economic and political limitations that threaten the realization of their grand project. As Chávez contends in a 2002 interview with Marta Harnecker, “There has been a change in the legal-political structure,” but “the essence of the socio-economic structure of the country, we have advanced very little.”11 Up to this point, Venezuela has heavily relied on its petroleum revenues as a means of contributing to the unification of the Americas as well as internal social progress. However, its oil reserves are not infinite. If and when oil runs out, or prices fall in the world market, and if Venezuela’s socio-economic structure continues to be tied to corporate power, the integration of the Americas will be limited in its reach and scope.

As for Cuba, the US-imposed blockade has asphyxiated the Cuban economy and hence its ability to initiate programs that go beyond its own survival. If the United States succeeds in advancing the FTAA, a proposed free-trade bloc that incorporates every country of the hemisphere except Cuba, Cuba will become further marginalized. Cuba’s future largely depends on change in the current balance of power, the coming into being of united anti-imperialist Latin America could bring about this transformation.

Since the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the pending Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), with many political leaders of the Americas signing on to a US agenda, a united counter-hegemonic force of the kind that Cuba and Venezuela seek is all the more difficult to muster. At this point, much of Cuba and Venezuela’s hope has rested on leftist leaders being swept into power by popular movements in Latin America. Unfortunately, Lula, Kirchner, and Vasquez (of Uruguay) have not fulfilled many of their electoral promises. While invoking populist and oftentimes anti-imperialist language, many of the supposedly “leftist” leaders have walked the centrist path, on their own or pressured by foreign capital and debt. Although Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay have contributed to TeleSur, promoting a shift from US domination of the media, their collaboration only goes as far as mounting a united counter-power to Northern hegemony. In many cases, they play by the rules of neo-liberalism, wishing that a United South America could outcompete the US and beat it at its own game.

Despite concessions and limitations, Cuba and Venezuela have met other nations willing to challenge the hyper-power to the North with open arms, in the hopes that the strength of their unity can encourage their neighbors to move in a more progressive direction.

Looking Forward

The election of Evo Morales in Bolivia holds great promise of a united anti-imperialist Latin America. Morales, an indigenous socialist, will assume the position of presidency in January of 2006. He has spoken to the necessity of the nationalization of natural resources, redistribution of wealth, and collaboration with Venezuela and Cuba, and he has openly condemned U.S. imperialism.

Directly following his election, Evo visited Cuba and Venezuela, signing cooperative agreements based on solidarity, humanism, and the advancement of Latin American integration. Evo and Fidel signed a bilateral agreement that Cuba will fully equip two eye care centers; one in La Paz and the other in Cochabamba, providing free eye care to Bolivians. Additionally, Fidel extended 5,000 scholarships for the training of Bolivian doctors and specialists. With the help of Cuba and Venezuela, a program to eradicate illiteracy in Bolivia will begin in July 2006. Evo and Chávez have agreed Venezuela will help Bolivia in organizing its Constitutional Assembly. Chávez has also promised to provide Evo’s government with a $30 million donation for social projects. Furthermore, Venezuela will supply all of Bolivia’s diesel fuel needs in direct exchange for Bolivia’s agricultural products.

Cuba and Venezuela’s demonstration of mutual-aid exchange, rooted in humanism and solidarity, is breathing life into ALBA. Now, as Bolivia joins their ranks, there is greater possibility for the vision of Martí and Bolívar. Evo Morales shares this vision, as he has stated: “[t]ogether, united, we are going to change history, not only in Bolivia but in all of Latin America and free ourselves from US imperialism.”12

1 Brian Lyons and Rich Palser (2005), Cuba and Venezuela: Breaking the Chains of Underdevelopment in Latin America, North London Cuban Solidarity Campaign, pp. 71-73.

2 Named after Simón Bolivar’s friend and teacher Simón Rodríguez, who changed his named to Samuel Robinson after Robinson Crusoe.

3 Richard Gott (2005), Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution, Verso, p. 258.

4 Gott, pp. 257-258; Lyons and Palser, pp. 69-73; Claudia Jardim, “Prevention and Solidarity: Democratizing Health in Venezuela,” Monthly Review 56.8, January 2005. Also see, Hugo Chavez’s speech to the United Nations in New York City, 2005.

5 Peter Maybarduk, “A People’s Health System: Venezuela Works to Bring Healthcare to the Excluded,” Multinational Monitor, October 2004; and Gott, p. 257.

6 “Part of Mr Chávez’s popularity stemmed from the Petrocaribe Initiative that Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela SA, signed last June with 13 Caribbean and Central American countries. It codified a scheme dating back to October 2000 which gave the signatories up to 15 years to pay for Venezuelan oil with a nominal two per cent interest at $20 a barrel, one-third less than the prevalent price of $30. The updated scheme enabled the signatories to pay only $40 a barrel instead of the market rate that shot up to nearly $70 in October” (Dilip Hiro, “Power of Oil,” The Statesman 13 January 2006).

7 Steve Ellner, “Venezuela’s ‘Demonstration Effect’: Defying Globalization’s Logic,” NACLA, reprinted in Venezuelanalysis.com 17 October 2005; Marta Harnecker (2005), Understanding The Venezuelan Revolution: Hugo Chávez Talks to Marta Harnecker, trans. Chesa Boudin, Monthly Review Press, p.120.

8 Fidel Castro wrote these words in his book War, Racism, and Economic Injustice: The Global Ravages of Capitalism (Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2002, pp. 63-64), cited here from Lyons and Palser, p.77.

9 See Hugo Chavez’s speech to the United Nations, 2005.

10 Harnecker, pp. 113, 120-23.

11 Ibid. p.107.

12 Joaquin Rivery Tur, “A Brotherly Encounter: Fidel Castro and Evo Morales Sign Bilateral Cooperation Agreement,” Granma 1 January 2006.

Cory Fischer-Hoffman has organized and participated in actions at the recent trade meetings in Cancun, Mexico, and Miami, Florida. Greg Rosenthal is an undergraduate student and activist at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.