There was a subtle difference in both groups this year — many said they noticed it.

As in every year, tens of thousands of Germans visited the Memorial Site of the Socialists in an eastern section of Berlin and placed red carnations at the tall memorial stone honoring Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, or the surrounding wall with its plaques marking the lives and deaths of socialist and communist leaders of the last century, from founders of the Social Democracy who died before World War One to men and women who fought the Nazis in Spain, in exile, or in prisons and death camps andbuilt up the German Democratic Republic as best they could but died — mercifully — before its downfall.

As in every year, tens of thousands of Germans visited the Memorial Site of the Socialists in an eastern section of Berlin and placed red carnations at the tall memorial stone honoring Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, or the surrounding wall with its plaques marking the lives and deaths of socialist and communist leaders of the last century, from founders of the Social Democracy who died before World War One to men and women who fought the Nazis in Spain, in exile, or in prisons and death camps andbuilt up the German Democratic Republic as best they could but died — mercifully — before its downfall.

The annual commemoration grew out of the giant protest of German workers mourning Karl and Rosa, leftist Social Democrats who opposed World War One, who were murdered on 15 January 1919, two weeks after helping to found the Communist Party. It became a tradition during the era before Hitler, who had the beautiful memorial by Mies van der Rohe demolished.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Berlin, 1926

The tradition was revived in GDR years and, although it took on aspects of formally “honoring the leaders,” probably remained the most popular celebration in Berlin. Since then, in a far opener spirit, it repeatedly surprises the media and the “experts” with its size. This year, again, they underestimated the participants radically, counting only 20,000 when probably three or four times that number took part.

As ever, there were two groups. One marched several miles along Karl Marx Allee with loudspeaker trucks, music, fiery speeches, and even more fiery banners and slogans. Alongside trade union youth and anti-fascist organizations were columns from every imaginable left-wing organization. Some seemed to be calling for the revolution in a week, others next afternoon. Hammers and sickles abounded, so did the faces of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Che, and of course Rosa Luxemburg — and even of Josef Stalin or Mao Tse-tung. In the loud, colorful crowd, not only German dialects from all Germany but many other languages were frequently heard — especially Turkish, the language of the largest minority in Germany, but also Kurdish, Greek, Persian, and Arab. This was the day when each group tried to demonstrate its importance and its militancy.

The other group, far larger and quieter, consisted largely of East Berliners carrying on the tradition of honoring Karl and Rosa, meeting old friends and comrades still true to the cause “despite everything” (or as, Karl Liebknecht said in German — “Trotz alledem”) and wishing to register a lasting belief in their ideals of a better, socialist Germany and a world at peace.

Neither group quite understood the other. The strange hairdos and clothes — though far less marked this year — and wildly revolutionary slogans of the former disconcerted or even shocked the latter — many ordinary East Berliners who, to the former, seemed very bourgeois. Attempts were made in past years to use such differences to split the commemoration and wreck it. But this year again, several blocks before the cemetery entrance, both those who had marched and those who came by subway mixed quite peaceably well before the final destination.

But was it purely imagination which made the crowds this year seem not only larger but somehow more hopeful?

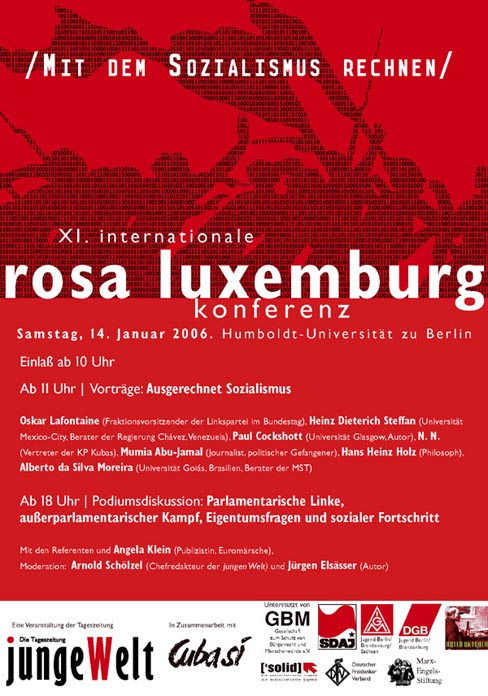

A possible clue is found in another tradition: the annual international Rosa Luxemburg Conference, held one day before the day of commemoration. On the day of the annual conference, every publisher of left-wing books and pamphlets — as well as every party and organization on the left, down to the tiniest — opens a stand in a section of the Humboldt University building in East Berlin. Inside the auditorium of the building, seating perhaps 800, is the annual conference held.

Among the conference speakers in past years were prominent people like Angela Davis and Evo Morales, soon to be president of Bolivia. A Cuban speaker is welcomed nearly every year, and a sign of solidarity is also offered now to Venezuela. And every year, Mumia Abu-Jamal, the African-American journalist threatened with execution in Pennsylvania since 1982, sends a recorded message from his cell on Death Row.

Especially of interest to many this year were the speeches by Heinz Dieterich Steffan of the University of Mexico City and Paul Cockshott of Glasgow University. Both of them demonstrated, in quite learned language which never failed to fascinate the overfilled hall, that the countless academic and media proofs of the impossibility of socialism are all flawed. It is capitalism which is basically flawed, they insisted, and both analyzed, in very different ways, why it not only must but can be replaced by a new democratic socialism.

Then, after a fine musical group, came the most interesting speech of all. Oskar Lafontaine from south-western Saarland, once a leading Social Democrat who left his party when it broke with its principles, is co-chair of the parliamentary caucus of the Left Party in the Bundestag, along with Gregor Gysi from the PDS, or Party of Democratic Socialism, which is centered largely in eastern Germany. Lafontaine is now leader of the Electoral Alternative for Jobs and Social Justice (WASG). The two groups plan to merge into a single party next year. His clear, sharp speech attacked all four old and new government parties and showed how their constant misuse of key vocabulary has hidden the fact that their program never could decrease joblessness but only increase it. What is required to tackle unemployment is not cutting social benefits and lengthening weekly working hours but the opposite. Not privatization and deregulation but, again, the opposite. Above all, unity is needed between the Left delegates in the Bundestag and those fighting in the factories, the schools and colleges, and in the streets. The PDS and WASG are facing differences in some provinces (above all in Berlin itself) — on the issue of PDS participation with the Social Democrats in the government. But here, too, Lafontaine suggested ways of solving problems.

Lafontaine expressed his conviction that a Left, far more united than ever before, can now make a difference in Germany. After years of doubt and despite past quarrels, new hopes have already attracted new groups and new voters and seem to offer a chance to fight together and move closer to the ideals of Karl and Rosa. And that seemed reflected in this year’s demonstration.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).