“He’s not always as ambitious as he could be, and he’s better on dishonesty than he is with feelings of warmth . . . He’s a good guy, and he’s definitely an auteur. Which is not to say that every film is an artistic success.”1

— Jacques Rivette on Woody Allen

In a movie career spanning 40 years (and ongoing), Woody Allen has gone from cultural icon to washed-up hack to born-again auteur. As famous for his off-screen life as for his artistic endeavors, Allen has gone his own way making the films he wants to make.

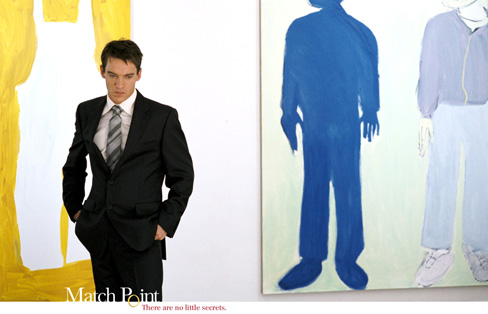

Such independence and resoluteness has brought us Allen’s 35th feature Match Point, a film that divided critics: some saw an artistic re-birth while others complained about yet another serving of the same shtick, gussied up with an English accent this time. While I agree that Allen is again mining ideas and concepts that have intrigued him for a lifetime, I wonder how many of these attacks of Woody fatigue are results of previous misunderstandings of his work as well as a reluctance to engage the darkness of his vision.

As Jacques Rivette notes in the epigraph for this article: Allen’s best (and main) preoccupation is with dishonesty in all of its manifestations. Allen conceives of the world as a place where dishonesty, arbitrariness, and luck are decisive factors and most pursuits end in failure. Annie Hall (1977) is a romantic comedy where everyone ends up alone; Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) demonstrates that murder can go unpunished, shallowness is rewarded, and intense guilt dissipates with time; The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) ends with the heroine still living in Depression-era New Jersey and trapped in an abusive marriage. When critics and fans alike deplore Allen for having stopped making funny movies, I ask myself: when exactly did he ever make them? Admittedly, the comedic elements of his films can serve to alleviate some of the gloom, but Allen’s vision is a pessimistic one. Even the nostalgic Radio Days (1987) ends by acknowledging the gulf between the images we conceive for our radio heroes and the reality of their private lives and existences.

Set in sleek Thames-side apartments, countryside estates, and all manner of London hotspots, Match Point tells the story of Chris Wilton, tennis pro turned social climber and (ultimately) murderer. The moral vacuity of the world Allen depicts is contrasted with the luxury and comfort of its trappings. This is a world where trays of cold lemonade or iced Champagne are always at the ready. It is also a world where the long-desired and desperately wanted child is handed off to the care of a (non-white) nanny as quickly as possible.

As usual, some critics have mistaken Allen’s depiction of opulence for an endorsement of it. In his Village Voice review, Michael Atkinson calls Allen “one of this nation’s most unapologetic wealth pornographers,”2 while Joanne Laurier on the WSWS website comments that “Allen paints these layers in a generally positive light.”3 The sight of self-absorbed, bigoted people acting with no concern other than their own self-interest is a “positive light”?

A further problem for Laurier is the comparisons critics are drawing between the film and Theodore Dreiser‘s An American Tragedy — comparisons she labels “an unjustified slight against the great novel.” What she ignores is that Match Point unfolds in a post-Dreiserian, late capitalist world. Chris Wilton is Clyde Griffiths 75 years later — hungering for the best life has to offer and not too particular about how he achieves it.

While Dreiser renders Roberta’s drowning with ambiguity, Allen portrays Wilton’s killings as the pre-planned actions of a murderer. Match Point is Dreiser updated, letting us know that the situation has only gotten worse. In contrast with Clyde Griffiths, Wilton’s desire to maintain his wealth and position is clear.

Allen’s pessimism extends even to whether or not Wilton will be found out by the police. Although the investigating detective does figure out what happened, a stroke of luck puts an incriminating piece of evidence in the pocket of a dead drug addict who is then blamed for the murders. In this most Hobbesian of worlds, the only thing to hope for is to be on the right side of a lucky break.

Match Point is a cinematic representation of George Bush’s Ownership Society with Chris Wilton as its paradigmatic citizen. He is bold, daring, ruthless, and — above all else — self-justifying in the pursuit of his own best interests. In a 2004 speech, Ted Kennedy characterized this outlook as a return to “the ideas of the distant past, 19th century ideas which America rejected in the early years of the last century.”4

How appropriate then that Woody Allen has set one of his darkest films in London, a city where a person can suddenly be confronted with the 19th century just by turning a corner. As much Dickens as Dreiser, Match Point is Allen’s chronicle of the cold, indifferent world we now call home.

1 Frédéric Bonnaud, “The Captive Lover — An interview with Jacques Rivette,” Trans. Kent Jones, Senses of Cinema 16 (September – October 2001). Accessed 31 May 2006.

2 Michael Atkinson, “Serve and Folly,” Village Voice 27 December 2005. Accessed 31 May 2006.

3 Joanne Laurier, “Woody Allen directs Match Point: No Dreiser,” WSWS 8 February 2006. Accessed 31 May 2006.

4 Edward M. Kennedy, “Creating a Genuine ‘Opportunity Society,'” CommonDreams.org, 12 March 2004. Accessed 31 May 2006.

Brian Dauth is a queer essayist and playwright living in Brooklyn with his husband Terrance. His work has appeared in Senses of Cinema (on the careeer of Jsoeph L. Mankiewicz), The November 3rd Club (on Brokeback Mountain and The Reception), and MRZine (on Manderlay, Find Me Guilty, and No Way Out).