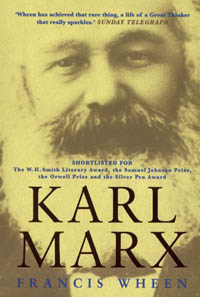

KARL MARX: A Life by Francis Wheen BUY THIS BOOK |

It is fitting that a man who framed a dialectic based on violent contradiction — on thrust and counter-thrust, struggle and counter-struggle — should have lived a life fraught with contradictions. In Francis Wheen’s biography, Karl Marx is neither hero nor nemesis, but a man of deep and unremitting conflicts, whose life bore witness to the contradictions of his time.

Marx was an unusual revolutionary. He was, Wheen says, “a Prussian émigré who became a middle-class English gentleman; an angry agitator who spent much of his adult life in the scholarly silence of the British Museum Reading Room; a gregarious and convivial host who fell out with almost all of his friends; a devoted family man who impregnated his housemaid; and a deeply earnest philosopher who loved drink, cigars and jokes.”

Wheen admires Marx’s achievement, but eschews the deference so often shown by Marx’s defenders. He pays tribute to his subject’s genius, but excuses nothing. He offers an intimate portrayal of Marx, who styled himself a modern Prometheus: but his Titan, afflicted with piles, carbuncles, and a choleric temper, is thoroughly mortal and thoroughly fallible.

Wheen draws liberally on Marx’s letters to Engels, whose generosity allowed Marx a scholar’s leisure. It is these letters — so witty, so entertaining — that show Marx at his worst. They reveal that, though he was a rabbi’s grandson, Marx was not immune from anti-Semitism: in several letters to Engels he described his rival, the German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle, as “wily Ephraim,” “Baron Izzy,” and “the Jewish nigger.” They show him incensed by the antics of his son-in-law, the Creole Paul Lafargue, “who has the blemish customarily found in the Negro tribe —no sense of shame, by which I mean shame about making a fool of oneself.” And they show him gravely worried by his daughters’ social standing: without several cases of claret and Rhenish wine for their dancing parties, he fears, they may “lose caste.”

Despite these rare lapses, Wheen notes, Marx’s correspondence with Engels and other revolutionary leaders has the power to fascinate and astonish. Wheen renders further service by acquainting his readers with the brilliance of Marx’s reportage. As the European correspondent of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, Marx reported the wars, revolutions, coups and counter-coups that transfixed Europe in the 1850s. His journalistic style was marked by a saber-like irony that spared few of his subjects. What Marx wrote of Lord Russell, a feckless British minister, could be applied to George W. Bush without the slightest revision:

“No other man has verified to such a degree the truth of the Biblical axiom that no man is able to add an inch to his natural height. Placed by birth, connections and social accidents on a colossal pedestal, he always remained the same homunculus — a malignant and distorted dwarf on top of a pyramid.”

Marx’s journalism did not escape the notice of a President whose savvy and charisma far eclipsed Bush’s. In a speech to a convention of newspaper publishers, President Kennedy once alluded to Marx’s poorly-paid labors on behalf of the Tribune, for which Marx penned(with substantial assistance from Engels) some five hundred articles on world affairs. Had the Tribune‘s miserly editors paid Marx what he was worth, Kennedy said, he might never have written Capital, contenting himself, instead, with an occasional squib for the Tribune’s informed readership.

The brilliance of Marx’s journalism is only surpassed by the masterpiece that Kennedy loathed, his treatise on capital’s rise to dominion. Wheen offers an unusual perspective on Marx’s Capital, which he asks to be read as “a work of the imagination: a Victorian melodrama, or a vast Gothic novel whose heroes are enslaved and consumed by the monster they created.” (Like a hideous fantasy, wrote Marx, “Capital comes into the world soiled with mire from top to toe and oozing blood from every pore.”) Wheen’s suggestion that Capital be read as fiction seems ludicrous — until one discovers how crucial fiction was to Marx, who planned to pen a thorough study of Balzac‘s Human Comedy after completing Capital‘s last volume.

Had it not been for cigars, cheroots, and cheap beer — and working himself to exhaustion, year after year, in a cause that made him hated — Marx might have begun, and finished, his study of Balzac’s masterpiece. Wheen gives us good reason to congratulate ourselves that Marx finished what he did.

Even Marx’s detractors on the right owe him praise for his efforts. Like the character in Molière‘s Bourgeois Gentleman who was stunned to discover that all his life he had been speaking prose, conservatives who spurn Marxist theory may be surprised to realize that modern historiography, with its strong emphasis on business and technology, owes many of its most striking insights to Marx. The same conservatives may find themselves in unwonted sympathy with Marx’s fear of Russian imperialism. A Prussian Rhinelander, Marx abhorred the Tsars’ despotic rule, and was a Russophobe to the core. In his Secret History of the Eighteenth Century — a pamphlet discreetly ignored by the Soviets, who omitted it from their exhaustive edition of his Collected Works — Marx claimed that Russia had, since the days of Peter the Great, sought world hegemony, “exalting itself from the overthrow of certain given limits to the aspiration of unlimited power.” The American ideologues of the Cold War couldn’t have said it better.

Marx’s critics are wont to blame him for the wrongs done by the Tsars’ inheritors. Wheen has little patience for this accusation. “Only a fool could hold Marx responsible for the Gulag,” Wheen says, “but there is, alas, a ready supply of fools.” Marx was no proto-Stalinist, says Wheen. He did not foresee Stalin’s program of state purges, famines, and forced industrialization; his socialism was not the socialism of the truncheon-wielding NKVD. He could — and did — despise and revile his enemies; but he never tried to engineer their demise. An admirer of Enlightenment philosophy, Marx respected the radical heritage of the French Revolution, and his ideals found rough incarnation in the radically democratic Paris Commune — not the Russia of Stalin’s assassins. His faith in the Communards’ eventual victory, though quickly dashed, was no pretense; and it belies the claim that Marx was an advocate of totalitarian rule.

Marx championed the egalitarian ideals of the meteoric Commune. Its lawmakers, paid only workingmen’s wages, were “responsible and revokable” — men chosen by direct election, responsible to their electors, and recallable at their electors’ will. These principles of popular government framed a state that Engels, in his introduction to Marx’s Civil War in France, deemed the model of the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” With its democratic underpinnings, the Commune bore no resemblance to Stalin’s regime; its ideals, and the ideals of its fighters, were manifestly not those of the Gulag. Marx was its most able apologist. Its ideals were his own. Like the Communards whose courage he exalted, he was no partisan of tyranny, no predecessor of Stalin. His path, long and grimly labyrinthine, was the path of liberation.

Marx’s unflagging militancy colored every aspect of his life and career. Even his relations with his children were refracted through a revolutionary lens. (It’s said that Marx wrote the most blistering pages of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon while his children were playing a game of horse and rider; whipped to “giddap,” Marx found himself in the role of the horse.) All three of his daughters — Jenny, Laura, and Eleanor — embraced their father’s faith in the coming triumph of the socialist commonwealth. Jenny and Laura married prominent socialist leaders. Eleanor translated Prosper Lissagaray’s history of the Commune, traveled extensively in the United States to research her study of The Working-Class Movement in America, and sought, in her brief life, to defend the hope of international solidarity. She wore a crucifix in honor of Ireland’s rebels, but, unlike her father, never denied her Jewish ancestry: an orator endowed with the talent of an actress, she once appeared before an audience of East Enders as a radical “Jewess.” Like her sisters, she adored her father — who rewarded her by refusing to sanction her proposed marriage to Lissagaray, a hero of the Commune’s barricades.

In a brief appendix, Wheen gives us Marx’s own “Confessions,” written in answer to a parlor game interview by his daughters sometime in the 1860s:

“Your chief characteristic?” “Singleness of purpose.”

“Your idea of happiness?” “To fight.”

“Your idea of misery?” “Submission.”

“Your favorite hero?” “Spartacus.”

“Your favorite color?” “Red.”

* * * * *

An excerpt from Karl Marx: A Life:

Midway through The Civil War in France [Wheen writes], “Marx . . . paus[es] to consider the lessons of the Commune [of 1871]. He quotes a manifesto of 18 March which boasted that the proletarians of Paris had made themselves ‘masters of their own destiny by seizing upon the governmental power.’ A naive delusion, he argues. The working class cannot simply ‘lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes’: one might as well try playing a piano sonata on a tin whistle. Fortunately the Commune had quickly taken the point by getting rid of the political police, replacing the standing army with an armed populace, disestablishing the Church, liberating schools from the interference of bishops and politicians, and introducing elections for all public servants — including judges — so that they would be ‘responsible and revocable.’ The Communal constitution restored to society all the forces hitherto absorbed by the state, and the transformation was visible at once: ‘Wonderful indeed was the change the Commune had wrought in Paris! . . . No longer was Paris the rendezvous of British landlords, Irish absentees, American ex-slaveholders and shoddy men, Russian ex-serfowners, and Wallachian boyards. No more corpses at the morgue, no nocturnal burglars, scarcely any robberies; in fact, for the first time [in many years] the streets of Paris were safe, and that without police of any kind.’

Dean Ferguson is an editor of Transformation, a newly launched literary journal. He lives and works in San Francisco.

|

| Print