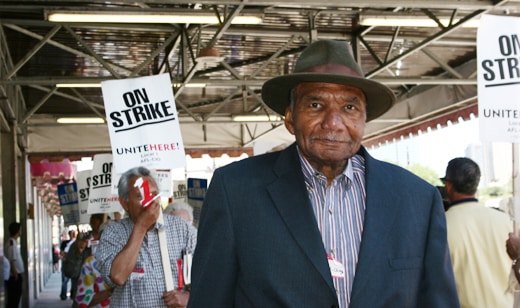

Frank Lumpkin. Photo by People’s World. |

A few days ago Frank Lumpkin died, a true American hero. I am still grateful that I was lucky enough to know not only him but his whole big fighting family!

I was fresh out of Harvard, a red diaper New York radical in 1949, set on working in a factory and the union movement, where, I was convinced, the main decisions would be made. There were no jobs in Syracuse, where I first landed, so the party organizer gave me a tiny note saying: Hattie Lumpkin, 263 Watson St. He had no money, nor did I, so I hitched my way and found the address, right in Buffalo’s black ghetto. In a rocking chair on the veranda of a rickety wooden house was a rather plain-looking woman; maybe the grandma, I thought. Could she tell me where to find Hattie Lumpkin? With just a little twinkle in her eye she answered the naïve-looking white kid: “That’s me, son!”

She took me in, fed me some southern dish (with okra), and sent me to stay with white comrades across town. “No sense being conspicuous if you want a job!” But first she slipped a ten-dollar bill into my hand.

I got a job and kept strictly to myself for the 3-month probation period. Even after that, often on late shift, the next year and a half was very lonely for me, a technical imbecile, trying not to betray my college upbringing in the worsening McCarthy hysteria. The one thing that saved me was the warmth I found in the Lumpkin house.

I found out that Hattie, her husband, the grandma, and ten sons or daughters had moved up from Orlando to find a halfway decent life. One daughter, Jonnie, later known as Pat Ellis, got in with a leftist crowd and joined the Young Communist League. Hattie, still religious, wanted to throw her out. But one by one Jonnie won them all over, including her mother, who became a leading Buffalo Communist — a fighter loved by all in the neighborhood, especially those whose evictions she helped reverse. Jonnie, a leader in the youth movement, recruited over a hundred new members in one campaign, got a job at Bell Aircraft, and made a fighting speech from the wing of a new plane while leading the campaign to get African-Americans including herself off jobs like sweeping and into production. She was a fighter.

And so was her brother Frank, a powerful boxer and then a steelworker, like several of his brothers, when there were jobs, that is. Frank told me in those days of his dreams of a better world, and even thought of how good life might be some day on a genuine cooperative farm.

But the world was cold in Buffalo in those McCarthy years. Spiting it, young ghetto people and white ex-students like myself formed a defiantly jolly, singing group of the new Labor Youth League — the child of American Youth for Democracy, which was the child of the Young Communist League, with each child smaller than its parent. When the pleasure liner to Crystal Beach in Canada decided not to sell tickets to “single males,” the group went to test them; our white “single males” got tickets; our black “single males” got none. We complained. Before we knew it two cops appeared. We continued to complain, peacefully, until one cop hit Frank over the head. While the blood poured, and we shouted, the second cop drew his pistol. Immediately Jonnie (Pat), nine months pregnant, threw her arms around her brother’s neck, weeping loudly and hysterically. It was an act, all right, one which probably saved him. Months later we were able to get Frank acquitted of attacking a cop. Before Buffalo, I knew nothing of ghetto life; my only acquaintance with African-Americans had been a couple of intellectuals. I hated racism but knew very little about it. I learned plenty!

I was drafted soon afterward, had McCarthy trouble, and fled the country (and the army). So I never met Hattie, Frank, Bessie Mae, or Gladys again.

From abroad, over the decades, I heard occasionally about Jonnie, a leader in Harlem and then, with her active, fighting husband Henry Ellis, in Chicago. And even more about Frank, and how he led laid-off steelworkers of Chicago in the long, hard battle for their rights. What an extraordinary family, a real American epic of fighters and leaders! For me, the Lumpkins were an education and an inspiration for as long as I have lived. For Frank, a true hero, we can only say “Presente”!

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

|

| Print