“Why don’t you Americans drop the bullshit about the land of the free and the home of the brave? Admit you’re now basically a tinpot dictatorship.”

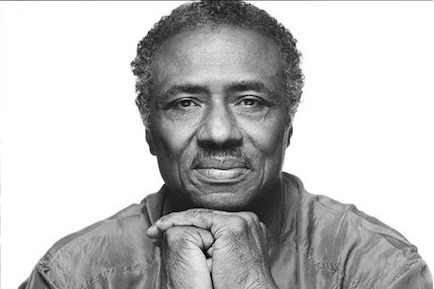

This, from my playwright friend Diane in London, with whom I’m Skyping. I’ve just told her about what happened to Herman Bell, my friend in prison. He’s a former Black Panther who turns 70 this January and has been locked up since 1974. On September 5, Herman survived a “beat-down” by five to seven white correctional officers half his age at Great Meadow prison—one of the more Klan-friendly joints in upstate New York. Two of Herman’s ribs are broken; he’s lost some vision in one eye; probably has a concussion.

Diane continues. “The mind fuck: ‘Everybody’s created equal?’ Please…”

I find it refreshing to hear my United States besmirched by a non-American (even one who shops at Banana Republic when she comes here). This means a lot when it pertains to Herman, who, after 40-plus years inside, only wants to get out on parole, to live what’s left of his life with his wife and grandchildren. Herman isn’t a saint; he isn’t my hero. He is my friend, one of the kindest, funniest people I know. Now, he’s badly hurt.

What happened to Herman isn’t unique in New York State, where brutal—sometimes fatal—assaults by guards on prisoners have persisted for years. As an American, though, I don’t usually hear about this, since the normalizing zeitgeist in this tinpot land o’ the free is that people behind bars—especially “convicted cop killers”—deserve whatever they get.

Herman’s beat-down happened when he was out in the rec yard. There’s a bank of phones there, and he was talking with his wife, Nancy, who was coming in a few days for a contact visit—their first in almost three years. Herman and Nancy have been allowed to see one another sitting across a divided table in a crowded visiting room. Recently, though, the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS) allowed them family, or “trailer,” visits, which is when a prisoner can actually be alone in a makeshift room with a family member for a day or two. Herman and Nancy were planning their first time in awhile being really together, when across the yard, a fight broke out. The officers announced the yard was closed, and Herman said to Nancy, “I got to hang up.”

Next thing he knows, one guard yanks Herman away, drags him into a hall where there are no surveillance cameras. Then he slaps the glasses off Herman’s face and starts in punching him. Other guards pile on, punching and kicking, and somebody sprays mace in Herman’s eyes and mouth. They try to pull off his boots and break his legs. When they slam his head repeatedly onto the concrete floor, Herman thinks that he is surely dying. But Herman never hits back. He knows how to act in prison. He never hits back.

I know this happened in this way because Herman is widely respected as a humble and peaceable man by the people incarcerated with him. One of them heard about the beating and called a friend outside. From there, word got to Herman’s lawyer, who managed to call Herman. Nancy stepped in. Immediately, people started working on his case…

Back at the prison, the guards, after beating Herman, do the usual thing cops do: they charge him with assaulting an officer. Herman is transferred to another prison and placed in SHU—an Orwellian acronym for “special housing unit,” which means solitary confinement.

About four days later, Herman and Nancy get one short, no-contact visit. Herman is brought in, beat-up and handcuffed, stumbling in leg shackles. He and Nancy have to yell through a hole in a thick Plexiglas wall.

At my regular therapy session, I describe all this.

“Herman must have done something,” says my therapist—a well-mannered, white, liberal American, who believes in balance, symmetry, and National Public Radio. “What did Herman do to cause this?”

“I don’t know,” I snap. “Maybe he didn’t hang up the phone fast enough? Maybe he was looking too black that day? If he’d raised one finger to defend himself, those thugs would have killed him. And if he’s convicted, he’ll spend an indefinite amount of time in SHU, lose any privileges, and kiss his last chance of parole goodbye.”

“I’m curious,” continues my therapist, who really did ask this: “If these officers are so thuggish and macho, why was Herman maced? Isn’t pummeling and kicking more satisfying than spraying a chemical into somebody’s face? Wasn’t Herman convicted of something serious?”

Pause. Inwardly, I reel at the degree to which TV shows like “Law and Order” have permeated even the most professional, free-to-be-you-and-me brain. I blurt out something rhetorical like, “How many US Army vets who wiped out whole villages in Vietnam or Iraq do we pass every day on the street? Do they spend any time in jail?”

“You have a big heart,” she counters. “But what life choices have you made that would attract you to a friendship with someone like Herman?

“Why shouldn’t I be friends with Herman?” I ask. “He’s a good person.” I realize this therapeutic relationship has reached its “sell-by” date. “You know what, lady?” I say, “you just asked the kind of what’s-in-it-for-me question that keeps us all in hell. It’s certainly keeping Herman in lockdown.”

Then I fire her.

Thing is, I believe Herman. I never had any doubt. I visited him maybe 10 days after his beating. With a “land-of-the-free” sincerity, Herman talked about the “right to remain innocent,” meaning everyone’s need to expect justice.

And here’s a fucking miracle: Evidently, DOCCS believes Herman, too. Because on October 5, they dropped his charges and moved him into general population at a prison closer to New York City. This bare-bones justice almost never happens—even to prisoners like Herman, with several hundred supporters mailing letters and making phone calls. That’s why we need to make this miracle an ordinary, procedural occurrence for everybody Herman describes as “the mass incarcerated and the voiceless.” Because we should not have to work so hard to prove that brutality is wrong. Because incarcerated people have human rights and can be believed.

Meanwhile, Herman remains in prison. “Let’s hope,” says my stalwart, non-American friend Diane, “that life will now unravel in a way that leads to Herman’s coming home.”