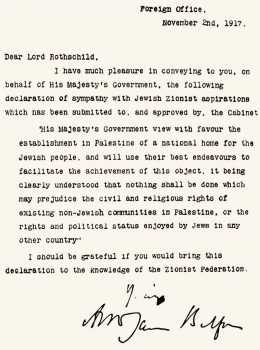

The coming months mark the centennial of Palestine’s forcible incorporation into the British Empire. In November 1917, British foreign secretary Lord Arthur Balfour declared his government’s support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”; in December, Jerusalem fell to British troops. One hundred years later, the effects of these events continue to reverberate. This should be a time of sombre reflection about international responsibility for the unfolding tragedy in Palestine.

This responsibility should weigh heavily on the West. Walid Khalidi put it well: “The Zionists were the initiators. But they were also, as they still are, the protégés of their Anglo–American sponsors and the emanations of their power, resources, and will.” The fact is that the Israeli state can’t be credited for much originality – either in its brutality or in the hypocrisy deployed to cover it. And it is all too fitting that it was British imperialism that propelled the Zionist movement onto the world stage.

Palestine was occupied, after all, amid one of the British Empire’s last great scrambles for territory in the Afro–Asian world. The scramble was pursued amid an outpouring of imperial self-adoration. Balfour was not alone in proclaiming, wherever and whenever he could, “the extraordinary novelty, the extraordinary greatness, and the extraordinary success” of the British Empire, a system drawn together, he insisted, not by “the bonds merely of crude self-interest, but the bonds of a common belief in a great ideal.” Freedom and justice marched with British troops. These may seem the banal platitudes of an imperial state. But during its “Great War,” the British state deployed them as never before. Its propaganda set a new world standard in its scale, its organization, and its impact.

Propaganda and Democracy

This is an appropriate time to look back to that propaganda and all that it revealed. The aspect of Britain’s wartime propaganda that has been most widely criticized is the manipulation of atrocity stories coming out of Belgium. That’s a reasonable place to start. The centerpiece of British atrocity propaganda was the “Bryce Report” of 1915, named after Viscount James Bryce. Bryce was chair of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages. As it happens, he was also a leading white supremacist and a pioneer of the kind of democracy that Britain helped Israel bring to the Middle East.

Those who know Israeli politics will find Bryce’s theories familiar. Democracy and self-government were, he insisted, the rightful preserve of civilized and conquering peoples. The key to democracy was therefore the establishment of a demographic basis for it. Africans, Asians, Indigenous peoples the world over – all were in Bryce’s judgement “subject races,” unfit for self-government. Only through colonial settlement and a restricted franchise could democracy flourish. Bryce lectured and wrote incessantly about “the risks a democracy runs when the suffrage is granted to a large mass of half-civilized men.” This great liberal’s theories were influential from Australia to the United States, and they attained near-biblical authority amongst settlers in South Africa.

Their application in Palestine, in turn, was made possible thanks to British power. This history was from the beginning steeped in propaganda. As the British war effort turned east, the Holy Land was a potent symbol. In the first instance it conjured images of the Crusades. Howevever, if the goal of Allied conquests was the defence of Christendom in the Levant, France had the stronger claim. British propaganda found a convenient alternative in support for Zionism. As Herbert Sidebotham, the Manchester Guardian’s military correspondent, explained, the Bryce Report didn’t have to do its work alone: “great as the ideal of relieving Belgium from the invader may be, the ideal of restoring the Jewish State to Palestine is comparably greater.” This could tap into deep public emotions, Sidebotham argued, and was another opportunity for Britain to deploy “ideal considerations as the allies of our military and political interests.”

No one did so with greater gusto than the Scottish writer John Buchan. Buchan is best remembered as the author of adventure novels, one of which, The Thirty-Nine Steps, was readapted for the screen in a feature film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. But he was also an accomplished propagandist. More even than Bryce, Buchan had built his public service around the imposition of white rule in South Africa. In early 1917 Britain’s Imperial War Cabinet selected him to direct the wartime propaganda service, with instructions to whip up public support for British war aims in the Middle East.

Buchan spun Britain’s eastern war as “the Last Crusade.” Tolerance and secular justice, oddly, were its supposed hallmarks. He assured his readers that the capture of Jerusalem by Allied troops was nothing less than “a parable of the cause for which they fought. They would recover and make free the sacred places of the human spirit which their enemies sought to profane and enslave, and in this task they walked reverently, as on hallowed ground.” Today we see what this freedom has brought to Jerusalem. Buchan’s propaganda itself suggested a politics that was far from ecumenical.

Where Buchan excelled, after all, was in channeling racism in service of state. This is what he had done for the Empire’s cause in South Africa, using a combination of nonfiction studies and novels. And it is what he did for the Great War. Some of his bigotry will ring familiar. So it is with his description of the menace of Islam, “a fighting creed,” Buchan warned, its fanatics taking to “the pulpit with the Koran in one hand and a drawn sword in the other.” Buchan’s racist depiction of Jews, on the other hand, have fallen out of favor in polite Western society. Here, for example, is his fictionalized image of who was pulling the strings in Germany: “a little white-faced Jew in a bath-chair with an eye like a rattlesnake. Yes, Sir, he is the man who is ruling the world just now, and he has his knife in the Empire of the Tzar, because his aunt was outraged and his father flogged in some one-horse location on the Volga.”

The antisemitism expressed by Buchan, and by the imperial establishment for which he acted as mouthpiece, squared more easily with support for Zionism than one might think. Jews were cast in various roles: as a subversive threat in Europe (Buchan did not forget the “Jew-anarchists”!); as a justification for Britain to hold Palestine; and as potential settlers, allies of the Empire in the east. These were not contradictions so much as a faithful expression of British settler colonialism. For Britain, colonial settlement was indeed a means of territorial expansion; but it was also a means of offloading the contradictions of industrial capitalism onto distant frontiers. Empire, as the Marxist literary critic Raymond Williams remarked, was represented in British culture as an “escape-route,” to which the ruined, the misunderstood, “the weak of every kind could be transferred.” This theme dovetailed with straight imperial calculations to structure British support for Zionism. A Jew settled in Palestine was a Jew not knocking on Britain’s doors. We would do well to remember that the first modern British statesman to clamp down on Jewish immigration, imposing the Aliens Act of 1905, was none other than Lord Balfour himself.

The worsening crisis in Palestine reflects more than a local record of colonial crimes, severe as these have been. Responsibility for it is global. Arundhati Roy was right to describe the Palestine tragedy as one of “imperial Britain’s festering, blood-drenched gifts to the modern world.” It is also a product of a history of racism and empire that extended across most of the West. On this centennial of the Balfour Declaration, reflection on this shared culpability should serve as a reminder of the responsibility for the political action that comes with it.