This article, originally written towards the end of 2003, is now published on our website for the first time in English. The odious Iraqi debt is still under-documented today, though it is highly relevant in our research and our proposals against all illegitimate, illegal, odious and unsustainable debts. It is a rare case where a creditor power asks for debt cancellation, pleading the odious nature of the debt. Of course, the USA made this move not because it was interested in achieving social justice, but as a political bargain in its imperialist enterprise in the Middle East, in order to strengthen its own economic power to the detriment of other creditor states.

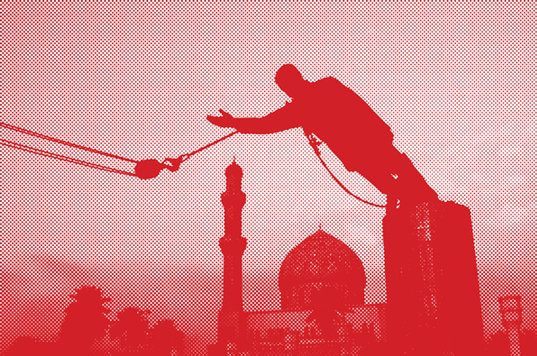

We now know the outcome of this imperialist enterprise: the U.S. war and occupation fuelled not only the physical destruction of Iraq but also its social disintegration, both of which were going on since the 8 year long war with Iran (which the U.S. supported by taking Saddam Hussein’s side) and had been continued by the Gulf War of 1990-1991 and the subsequent international embargo against Iraq. These destructions, added to the policy of “de-Ba’athification” of the country which led to the exclusion of the Sunni minority of the population from nearly all spheres of public life, in turn helped fuel the ranks of fundamentalist insurgent groups, including the ultra reactionary organization that was later to be known as the so-called Islamic State.

Despite the final objective of the use of the notion of odious debt by the USA in the case of Iraq, it is important to look into the matters of the Iraqi odious debt under Saddam Hussein and the imperialist policies pursued by the USA in relation to the public resources and debt of Iraq. It would be equally important to investigate the matter of Iraq’s public debt since 2003: what were the costs of the U.S. invasion and occupation of the country? What was the cost of the sectarian policy of de-Ba’athification? Who will pay for the reconstruction of Mosul and other areas that were entirely destroyed by the US-led coalition and the Iraqi army in their war against the so-called Islamic State? etc. These questions could be answered in future investigations, but one thing is for sure: the Iraq’s peoples’ right to self-determination cannot be guaranteed if the country’s economic and financial dependance to regional and international powers is forcefully maintained by these powers.

For 20 years the big powers (who are also the main creditors) have avoided putting the issue of odious debt into the spotlight, whilst the governments of the indebted countries didn’t contest their odious debt.

Suddenly on the 10th—11th of April 2003, the idea of odious debt appears in the speeches of the Bush administration. In these, they demand that France, Germany and Russia (who had been against the war on Iraq) should drop their claims on Iraq.

The international press seizes the demands and overtly and correctly mentions the odious debt. After a few days, most of the press no longer follows up the story, apart from the Financial Times, and very few other international papers (International Herald Tribune, Wall Street Journal).

The editorial staff of the Financial Times firmly oppose the idea of renouncing the debt. For the Financial Times, the same line would have to be applied to many countries of the developing world and to many former Soviet states. This could give the governments of indebted countries all sorts of ideas—in the end they will wish to have the same line applied to their own debts. Even if they themselves didn’t the social movements in their countries might pick up on the idea (e.g. in Brazil, or in South Africa where the debt of the apartheid-regime has now reached $ 24 billion). The Financial Times explained that the Bush administration was playing with fire and was putting creditors at risk 1.

What is an odious debt?

“If a despotic power (i.e. Saddam Hussein’s regime, the eds.) takes out a loan at odds with the needs and interests of the state in order to strengthen its despotic regime or in order to suppress the population who fights him, this debt is odious for the whole people of that country. This debt involves no obligation to the nation: it’s a debt of the regime, a personal debt of the power that took it ought, and for this reason it expires with the fall of that same power.” (Alexander Sack, Les effets des transformations des Etats sur leurs dettes publiques et autres obligations financières, Recueil Sirey, 1927). This abstract illustrates the case of an odious debt contracted by a despotic regime, but it is worth noting that according to Sack, debts need not be contracted by a despotic regime to qualify as “odious”. The concept of « odious » debt is perfectly applicable to Iraq.

The doctrine has its origins in the 19th century. It was applied during the Spanish- American war in 1898. Cuba, at the time Spanish colony, was occupied by the USA (as a “protectorate”) and Spain requested the U.S. to pay back the debt owed to it by Cuba. The U.S. refused and declared the debt to be odious, that is, taken out by a despotic regime in order to finance policies at odds with the people’s interest. What is important is that this declaration, accepted in the end by Spain, was laid out in an international treaty—the Treaty of Paris—and thus forms a judicial precedence.

Other cases : the debts incurred by Napoleon were renounced during the Restauration as“odious” and contrary to the interests of the French. After the American Civil war, the victorious North refused to take on the Northern debt which had been set for the defense of a slavery-based system.

After the First World War, the treaty of Versailles declared void the debt that the German Kaiser had taken out in order to colonise Poland and that it could not be transferred to the newly re-established Polish state. The dictatorial regime of Tinoco 2 in Costa Rica had run into debt against the British Crown. The Chief Justice Taft of the U.S. Supreme Court, who had been called upon to mediate in the judicial conflict (Great Britain vs. Costa Rica, 1923) decided that the debt was a personal legacy of the despot. The lending bankers shouldn’t be going after the democratic regime that followed Tinoco, but after themselves, who they had known about the despotic nature of Tinoco’s rule. Justice Taft added that the lenders were not able to show that they were trustworthy.

The doctrine of odious debt was first formulated by Alexander Sack (former minister of the Tsar, later professor of law in Paris, having emigrated to France after the revolution of October 1917) in 1927 in his compendium on the transfer of debt in case of regime change 3.

In the following thirty years, no debtor—to our knowledge—made use of the doctrine of odious debt in order to unilaterally renounce on debt or in order to call for mediation.

Jointly with other authors (in particular Jean-Claude Willame, 1986, Patricia Adams, 1991) and movements (Jubilee South Africa, Jubilee South) the CADTM have long been analysing Third world debts from this judicial point of view: the debts incurred by Mobutu (Zaire—Democratic Republic of Congo), by Habyarimana (Rwanda), by Marcos (Philippines), or Suharto (Indonesia), by the generals of the Argentinean dictatorship, by Pinochet in Chile, by the Uruguayan dictatorship, by the Brazilian dictatorship (in period 1964-1985, the Brazilian debt shot up from $ 2,5 to $100 billion—a 40-fold increase during the military rule), the debt of Nigeria, Togo, South Africa.

These are not old stories since the people of these countries are continuing to pay off these odious debts by taking out more debt. The Democratic Republic of Congo is a case in point : in 2003 the debt amounted to $ 13 billion—which corresponded more or less to the total debt that Mobutu took out since there has been virtually no new borrowing since he was ousted in 1997. The entire debt of the DRC should thus be dropped.

Why did the Bush administration back down on the odious debt?

On the 10th and 11th of April 2003, the finance ministers of the G8 nations assembled in Washington, where the Secretary of State of the US-Treasury, John Snow, demanded that Russia, France and Germany in particular should drop their odious debt towards Iraq. The USA made this demand not because it was interested in seeing the debt dropped, but as a political bargain, as a way of raising the stakes against countries that were opposed to the war. The idea was to find a way to convince France, Germany and Russia to change their position and thereby render legitimate the war. The idea was to make it possible for those who took military action to immediately start with the reconstruction of Iraq by using the oil revenues without having to service debt payments. The higher the outstanding debt before the war in 2003, the longer the USA and its allies would have to wait before they could be reimbursed for the costs of reconstruction.

Germany announced at the meeting of the 10-11 April that dropping the debt was not an issue, and that it would be rescheduled. The USA continued its haggling in order to convince France, Russia and Germany to make an effort concerning dropping the debt. In exchange for their goodwill, companies from their countries could expect to benefit from contracts linked with reconstruction.

Obviously the USA achieved concessions from the French and Russian side in the end. In fact, on the 22nd May 2003, the UN Security Council lifted its sanctions against Iraq and charged the U.S. designated Civil Administrator in Iraq, namely Paul Bremer, with the Iraqi oil exploitation (which had been under UN control 4).

The UN named Sergio Vieira de Mello as its representative in Iraq (in August, he is killed in an attack on the UN headquarters in Baghdad among with 23 others) with a much lower status compared to Paul Bremer.

Lifting the sanctions against Iraq means that companies, above all U.S. companies, can now do business in Iraq (the Financial Times titles on the 23rd May 2003: “UN removal of sanctions clears way for business”). That also means that all the assets of Saddam Hussein and of Iraq in general that had been frozen abroad (and again especially in the USA) for over 12 years are now “freed up”. As a result the USA are able to use them in their effort of reconstruction: the assets are not recovered by the Iraqi people. The Financial Times writes:“It (the lifting of sanctions by the Security Council, the eds) will free billions of dollars in frozen assets and future oil revenues from the UN control and place it at the disposal of coalition forces and interim Iraqi leaders to pay for reconstruction” (FT, 23 May 2003).

Some historical points of reference on the war on Iraq

In the 1980s, Saddam Hussein was supported by the USA and its allies in the war against Iran that caused over a million deaths. Iraq incurred debts to the USA and its allies. In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Several theories exist as to the reasons of this incursion, but it is not impossible that the Bush senior administration led Saddam Hussein to believe that such an aggression may not elicit any reactions, effectively setting him a trap. After the end of the first war, called Operation Desert Storm by the victors, Saddam Hussein was deliberately kept in power as the USA feared that the country (and its oil reserves) may otherwise fall into the hands of an uncontrollable revolution in the neighbourhood of Iran, itself uncontrollable. The allied troops let Saddam Hussein repress the uprising of Bassorah. The war was led with a UN mandate which included the freezing of all Iraqi foreign assets and an embargo. Later on the « Oil for food » program was added.

50% of the Iraqi oil revenues from this program were used to buy food and medicine. This figure is wholly inadequate in the light of the death of more than 500,000 children as a consequence of the embargo. The existence of this program was widely spread over the international opinion and was even used for propaganda purposes. However, the fact that 25% of the oil revenues were distributed to neighbouring countries in form of reparation payments was little known. The United Nations Compensation Commission (website : www.uncc.ch) had, since 1991 recognised the validity of reparation claims totalling $ 44 billion (which was only a part of the demands). The claims were filed by individuals, by companies and by governments. With a quarter of all revenues at its disposal, the UNCC handed out—until the war in April 2003—$ 17,6 billion to the claimants—prioritising individuals and families. In terms of reparation, $ 26 billion of reparation remain to be paid whilst payment has been stalled (Financial Times, 24th June 2003). This does not preclude the fact that absolute priority was not given to the satisfaction of the Iraqi population in terms of food and medicine when oil revenues were distributed.

In 2003, a US-led coalition attacked Iraq. Great Britain, Australia, the Netherlands and Denmark directly took part in military action whilst other countries gave support in various other ways. This coalition acted in violation of the UN Charta. It committed an act of aggression according to the UN Charta.

The impossible Iraqi debt

How high is the Iraqi debt? According to a 2002 study by the Department for Energy of the Bush administration it probably amounted to $ 62 billion. According to a joint study of the World Bankand the Bank of international settlements it totalled $ 127 billion, of which $ 47 billion in interest payments.

According to a private Washington think tank, the overall level of financial obligations of Iraq (debt, reparations and contractual obligations) was $ 383 billion at the beginning of 2003 of which $ 127 billion were estimated debt.

The creditor countries fall into two categories: members and non-members of the Club of Paris. The Club of Paris includes 19 creditor states and some invited guests (Brazil, Korea) following the fancy of the 19 founders. It estimates that it can claim $ 21 billion debts from Iraq, to which $ 21 billion of due interest payments must be added (source : FT 12-13 July 2003).

The second category comprises Arab countries (the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia), Turkey and some countries from the former Soviet Block (Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary) since turned staunch US-allies. These countries have a combined claim of about $ 55 billion in debt. More than half of this sum is claimed by the Gulf States (excluding Kuwait) but this debt is subject to a long-running legal challenge by Iraq. Iraq claims that the $ 30 bn. represented a gift by these countries in order to fight the war against Iran, while these assure that it was a loan. The two categories above regroup all bilateral debts (in total $ 97 bn).

The stakes aren’t as high for the private banks involved. They claim about $ 2 bn in debts (Bank of New York and JP Morgan being the main creditors).

Concerning the World Bank and the IMF, Iraq’s debts towards them is below $ 200 million.

In summary then, the negotiations between Iraq and its creditors concern, as a starting point of discussion, a sum of around $ 100 bn : 42 (Club of Paris) + 55 (other bilateral loans) + 2 (banks) + 0.2 (World Bank and IMF) = about 100. This sum does not includes the outstanding compensation claims (around $ 160 bn. for the 1990-1991 war), contracts which were concluded just before the outbreak of war ($ 90 bn.) and above all the new debts incurred since March-April 2003.

In reality, the main negotiation will take place between these creditors themselves and not between those creditors and the so-called Iraqi authorities that have been put in place by the USA. The creditors will have to fight over the following question: who will take the lead in renouncing some of the debt so as to make the repayment of the rest of the debt bearable? “Bearable” for the creditors here means that the debt can be paid back at the due date. No question of the creditors considering whether the repayment of the debt is bearable with respect to the needs of the Iraqi population. The USA will ask its colleagues in the Club of Paris as well as the Arab countries, Turkey, Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary to make a joint effort to reduce their claims by a third to two- thirds. If that turns to happen, the amount of bilateral debt could be limited to $ 65 bn (one third reduction) or even $ 32 bn (two thirds reduction), in stead of the original $ 97 bn (see above). The USA is keen to achieve such a reduction in order to be able to add to the already existing debts those arising from reconstruction. Many months of negotiations are therefore to be expected.

In this context, it is worth taking a look at the partition of the debt according to the two opposing fractions which evolved within the Club of Paris before the outbreak of war. At the famous meeting of the G7 Finance ministers on the 10-11 April 2003 in Washington, it should be remembered, the press noted that Russia, France and Germany were the main creditors of odious debt to Iraq. In reality, the figures are not as clear—as it can easily be verified on the table below where the debt of the War Fraction is contrasted to that of the « Peace-Camp ».

Iraqi debt to the Club of Paris (in $ mio.)

| « Peace Camp » | War Fraction |

|---|---|

| Russia : 3.450 | Japan : 4.100 |

| France : 3.000 | USA : 2.200 |

| Germany : 2.400 | Italy : 1.720 |

| Canada : 560 | Great Britain : 930 |

| Brazil : 200 | Australia : 500 |

| Belgium : 180 | Spain : 320 |

| Netherlands : 100 | |

| Denmark : 30 | |

| Sum : 9.790 | Sum : 9.900 |

Table compiled by the author, data source: Financial Times, 12-13 July 2003.

This table shows that the War Fraction has a greater claim of odious debt than the « Peace Camp », which was not the implication of the Bush administration’s discourse at the time of its blackmailing attempts in April 2003.

Let us remember that at the start of the negotiations the amount of debt had deliberately been exaggerated.

Also, the Club of Paris is claiming for the double of its due debt: it claims for $ 42,000 million instead of $ 21,000 million. How come ? Because the Club of Paris adds interest payments on outstanding debt for the period since 1992. This is an absurd demand, since with the sanctions against Iraq, the UN was in control of all the oil revenues. Furthermore, Iraqi assets abroad were frozen. Nevertheless, the Club of Paris has credited the interest (along with most of the other bilateral creditors) and the debt is now doubled. If the demand for interest payments is dropped during the course of the talks, the Club of Paris will present the reduction in debt of $ 21,000 million as a sign of generosity in front of the Iraqi public opinion and the International community.

Iraq and the threat of a vicious circle of debt

Whether they are as high as 50, 100, or 200 billion, the financial costs of Iraq are going to drag the country into a vicious circle of debt and therefore into a subordinate relationship with the creditors who will plunder oil reserves, with the United States helping themselves first.

To verify the value of this claim, let’s try to calculate what reimbursing the debt would imply in the future.

Imagine the following scenario: creditors agree to reduce their demands, and gauge the total amount of debt inherited from the pre-war period of March/April 2003 at around 62 billion (a 1/3 reduction, see above 5), to which 50 billion in reparations would be added.

Then several tens of billion in new debt linked to reconstruction would surely have to be added to that total, let’s say 38 billion for 2003-2005. Suppose that creditors postponed the beginning of repayment to 2005. In this hypothesis the total amount of debt and reparations weighing on Iraq would be around 150 billion dollars.

How will the creditors set up the reimbursement plan? One plausible hypothesis is the following: they would demand that the completely broke Iraqi authorities use oil revenues for repayment, and here several other problems arise.

First unknown factor: by 2005, will there be such Iraqi authorities with enough legitimacy to make commitments in the name of the State of Iraq (i.e. the Iraqi people)?

This is far from certain.

Second unknown factor: will oil production capacity have been fully re-established? In August 2003 production was barely at 300,000 barrels, compared with 1,700,000 before the 2003 war and 2,700,000 before the first Gulf War. The estimated cost of completely restoring oil production installations varies between 30 to 40 million dollars. Who will pay? How will the security of those companies in charge of restoring, then exploiting the fields be ensured?

According to the Financial Times (July 25, 2003), the major oil companies have met with Bush Administration representatives several times and have conveyed the message that it is out of the question for them to spend anything on restoring the production apparatus or on production itself as long as security cannot be guaranteed. Through Sir Philip Watts, president of Royal Dutch/Shell, transnational oil firms added that they themselves will determine when the future Iraqi regime meets the condition of legitimacy; “When authorities that are legitimate in the eyes of the Iraqi people are in place, we will meet and recognize them”! In other words, the firms are telling the Administration that the Iraqi authorities set up by the occupying troops do not meet the necessary conditions. Another part of the message is that they do indeed plan on having the government pay for the expense of restoring the production apparatus destroyed by the coalition. The message is a real slap in the face to Bush.

Third unknown factor: what will be the price of a barrel of oil in 2005?

Fourth unknown factor: will the oil industry be publicly owned? If so, much of the revenue will go into the State’s pockets, who will be able to put it toward debt reimbursement (should creditors so will it). This is a problem for the Bush administration’s desire to privatize as many companies as possible. If the oil industry is privatized, the State will only make tax revenue from the proceeds, even though it is the body that will have to pay off 150 billion in debts.

According to various sources, in the very best and very unlikely scenario, oil revenues will hover around $10-20 billion in 2005.

Now how much will the reimbursement of $150 billion cost annually? Let’s suppose that creditors will “accept” a reimbursement plan at a preferential fixed interest rate of say, 7% over 20 years 6. $150 billion to be repaid over 20 years at 7% represents an annual payment of about $18 billion (repayment on the interest and principal). In short, it’s like trying to stuff a square peg in a round hole. It is utterly impossible based on export revenue of between 10 and 20 billion.

Where was the United States with this problem in mid-2003?

A few days after the invasion of Iraq with American, British, and Australian troops had begun on March 20, 2003, George W. Bush estimated before Congress that the costs of the war for the U.S. Treasury would be around $80 billion. On September 7 2003, Bush declared to Congress that he was asking for $87 billion more. According to the PNUD and Unicef, $80 billion is exactly the extra sum needed each year over 10 years to guarantee universal access to drinkable water, basic education and health care (including nutrition), and gynecological and obstetric care for all women for the entire planet. This sum that no world summit of the last few years has managed to come up with (at Genoa in 2001 the G7 only raised a little under one billion dollars to fight against AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis), the U.S. government managed the feat of raising and spending it in a few months. That $80 billion Bush got from Congress, to which another $87 will now be added, is the same sum needed to destroy a certain amount of infrastructure and human life in Iraq and underwrite territorial occupation through the end of December 2003.

Confronting unexpected resistance, the USA is having the worst kinds of difficulties. Sure, it is clearly dominant on the international scene. Sure, it is occupying the country. But it is hated by a large part of the population. Its troops are constantly harassed. The cost of military occupation is much higher than foreseen; it is now at around $4 billion per month (48 billion per year) for over 130,000 soldiers currently serving. The British are there with 11,000 troops, but the 30,000 that were supposed to be supplied by other alliance members have yet to show up 7.

This doesn’t stop companies from the U.S. and elsewhere from doing business.

By the spring of 2003, the Halliburton company (from Texas) was already on the ground doing emergency repairs to oil production equipment for a $7 billion contract. Dick Cheney, U.S. vice-president, was the firm’s CEO until August 2000. Competitor Bechtel (responsible for water conflicts in Cochabamba in Bolivia) scored a $680 million contract for repairing the water and electricity distribution systems as well as certain means of communication called a meeting in Washington in May 2003 on the theme “How can a U.S. company participate in reconstruction” The 1,800 small and medium-sized businesses present cooled off considerably after being told that they would have to secure the safety of their employees and equipment themselves. Bechtel held the same kind of meeting in London and in Kuwait City.

The big agro-chemical corporations, in particular the Anglo-Swiss transnational Syngenta, are also interested in the future of Iraq as the country has traditionally been a big grain exporter. However, Monsanto has made it known that it isn’t interested, perhaps because of other pressing issues elsewhere…

On site, administrator Paul Bremer is flashing all the neo-liberal signals in order to draw investment; he has declared that everything must be privatized, that subsidies must be eliminated and private property rights increased. In exchange, he concedes the need for a social security safety net. We might get an idea of what he means by that when we remember that in May 2003, the United States paid 400,000 Iraqi workers and civil servants a monthly salary of $20, which adds up to $8 million total—500 times less than what the U.S. spends each month maintaining its own troops in Iraq.

Cancel Iraq’s odious debt and pay reparations

It’s not because the U.S. used the notion of the “odious debt” in an opportunistic way that we should refuse to demand it be applied in order to guarantee justice and fundamental rights for the Iraqi people. Therefore we must support the idea of a legitimate power in Iraq that could repudiate this debt. Reparation rights must also be broached. The cost must take into account the damages that the United States and other aggressors themselves never take into account: individual suffering, cultural pillage, etc., and for which they are nonetheless responsible since as an occupying force, they are supposed to ensure the security of people and property.

Applying the odious debt doctrine to Iraq would be of top importance for the future of the Iraqi population, and beyond that, for a majority of the populations of indebted or so called “developing” nations. The citizens of these countries are perfectly within their rights to demand that a significant portion of their countries debt be declared void based on the odious debt principle.

It belongs to the alterglobalization movement to put forward the demand that Iraq’s external public debt be cancelled, combined with other demands such as the retreat of occupation troops, the full exercise of their sovereignty by Iraqis themselves, which includes the use of their country’s natural resources, and the payment of reparations to Iraqi citizens for the destruction and pillage suffered over the course of the war started by the American/British/Australian coalition in violation of the UN charter.

George W. Bush, Tony Blair, and Jon Howard (Australia’s prime minister), along with the heads of the Danish and Dutch governments (these countries participated directly in the invasion) should also be prosecuted and sentenced as directly responsible for the crime of aggression, within the meaning given by the UN charter, and for war crimes.

As concerns proposals for Iraq’s debt, we should push forward on the following points:

- the debt contracted under Saddam Hussein’s regime is an odious debt and

therefore void; - a subsequent democratic regime should refuse to take responsibility for that debt and would have the right to repudiate it;

- new debts due to the costs of war and reconstruction are also odious and

therefore void; - the victims of Saddam Hussein, those of American aggression, of pillage, and the current occupation have the right to reparations;

- finally, as for citizen action and the action of public authorities: we must

participate in general mobilizations, in petitions like that of the CADTM (See the text of the petition hereafter), but we must also demand audits from public authorities (although not necessarily wait for them, but organize our own citizen’s audits) on the debts that creditors are claiming against Iraq. What are they? Any creditor claiming reimbursement of a debt from Iraq must answer citizen’s questions on the nature of these debts. In what contract are they defined? Who were the contracting parties? What were they for—arms? civilian equipment? What were the contract terms? What amounts have already been paid? Doing the research work here may contribute to showing that the debts at stake are in fact odious.

Petition for the abolition of Iraq’s debt and demanding reparationsWe, the citizens of many countries, unite in declaring that the Iraqi people cannot be held responsible for debts contracted and expenses run up by Saddam Hussein and his despotic regime. Under the terms of the doctrine of odious debt, these debts fall with the regime that contracted them. Nor should the Iraqi people have to bear the cost of the occupation of Iraq by the troops of the Coalition of the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. We call on all creditors to cancel the odious debt contracted by Saddam Hussein. We declare that the cost of the war and the present occupation cannot be transformed into a further debt. We consider that the destruction and pillage caused by the war entitle the Iraqi people to reparations. We call upon the United Nations General Assembly to support the Iraqi people in demanding the cancellation of the debt and the provision of reparations for the damage caused by the war waged by the Coalition in violation of the United Nations Charter. The Iraqi people and their freely elected representatives must be allowed to enter a new stage of their history with full independence. In the future, all Iraq’s resources must be made available for use by and for the Iraqi people, so that they can reconstruct their country. We call on all countries, all organizations and all citizens to support this declaration. First signatories : Acosta Alberto (Univ. de Cuenca, Ecuador), Albala Nuri (lawyer, Paris) ; Badrul Alam (secretary general Bangladesh Krishok Federation, Bangladesh), Boudjenah Yasmine (European deputy GUE/NGL, France), Bugra Ayse (Univ. Bebek of Istamboul, Turkey), Chomsky Noam (United States), Cirera Daniel (French Communist Party international relations), Cockroft James (author, United States), Comanne Denise (CADTM-Belgium), Eliecer Mejia Diaz Jorge (lawyer, criminal law specialist, France), Gazi Carmen (architect, CADTM president-Switzerland), Gillardi Paolo (Anti-war coalition, Mouvement pour le Socialisme, Switzerland), Gottschalk Janet (Medical Mission Sisters’ Alliance for Justice), Hediger André (Mayor of Geneva, Switzerland), Husson Michel (economist, France), Khiari Sadri (Artist-painter, CNLT, Raid Attac, Tunisia), Kitazawa Yoko (Japan Network on Debt and Poverty, Peace Studies Association of Japan), Krivine Alain (European deputy GUE/NGL, France), Künzi Daniel (filmmaker, Municipal council of the City of Geneva, Switzerland), Lambert Jean-Marie (international law professor at Univ. cathol. de Goiás, Brazil), Magniadas Jean (Doctor of economic science, honorary member of the Economc and Social Council, France), Martinez Cruz José (Independent Human Rights Commissioner, Morelos, Mexico), Maystre Nicolas (student, CADTM-Switzerland secretary), Mendès France Mireille (lawyer, Paris) ; Millet Damien (CADTM France secretary general), Nieto Pereira Luis (Asociación Paz con Dignidad, Spain), Nzuzi Mbembe Victor (farmer, GRAPR, Democratic Republic of Congo), Pazmiño Freire Patricio (lawyer, CDES general coordinator, Ecuador), Pérez Casas Luis Guillermo (José Alvear Restrepo lawyers collective before the EU and the United Nations, Columbia), Pérez Vega Ana (Univ. de Sevilla, Spain), Piningre Denis (filmmaker), Pfefferkorn Roland (sociologist, France), Said Alli Abd Rahman (Perak Consumers’ Association, Malaysia), Saumon Alain (president CADTM-France), Soueissi Ahmad (Nord-Sud XXI), Theodoris Nassos (lawyer, Greece), Toussaint Eric (CADTM, Belgium), Verschave François-Xavier (author, France), Yacouba Ibrahim (National network “debt and development”, Niger), Ziegler Jean (writer, North-South Foundation for Dialog, Switzerland). |

Footnotes

1 Renouncing the odious debt would in any case not cause the bankrupt of large banks, as the odious debt represents, on average, less than 5% of their turnover. But the bankers and other creditors tend to believe that they have an undeniable right to lend to whoever they wish. Similarly, they are convinced they have the right to demand repayment whatever the circumstances of the debtor.

2 See Damien Millet, Eric Toussaint, Debt, the IMF, and the World Bank: Sixty Questions, Sixty Answers

3 Alexander Sack was convinced that debts should in general be carried on from one regime to the next, except for for odious debts.

4 Between 1991 and 22 mai 2003, the Iraqi oil was controlled by the UN.

5 This corresponds to the Bush Administration Energy Department estimate made in October 2002.

6 In August 2003, Brazil was paying an interest rate of 12-14% to borrow on the international market, Argentina was paying 37-39%, Turkey 7-9%, the Philippines 6-7%, Mexico 5%.

7 The allied commitments for troops in the spring of 2003 were in principle the following : Spain: 1,200 soldiers, Poland 2,000; Ukraine 2,300; Norway 140; Italy 2,800; Romania 520; Portugal 130; the Netherlands 1,100; the Czech Republic 300; Denmark 450.