Last week, Thomas Frank welcomed Paul Krugman to the ranks of those who believe that the American working-class in recent decades has often voted against its fundamental economic interests by supporting conservative Republicans.

Appropriately enough, Frank then chastises Krugman for having repeatedly used his New York Times column to argue exactly the opposite, denying the idea that working-class Americans had defected to the Republican Party.

Frank, the author of What’s the Matter with Kansas? then draws the appropriate conclusion: that the tendency on the part of Krugman and other liberals to underestimate working-class conservatism, in both southern and northern states, prepared the way for Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election of November 2016.

To be clear, we’re not talking about the entire American working-class. Working-class whites have been more likely to vote against their economic interests and to be persuaded by the kinds of cultural, identity issues raised by Trump and other Republican politicians. Not so with Hispanics, latinos, and other members of the American working-class—although, according to Stephen Morgan and Jiwon Lee, minorities did have lower turnout in competitive states in 2016.

But I think Frank and Krugman have it only half right. Their view is that the working-class, if it voted according to its economic interests, would stop supporting Republicans and return to the Democratic Party fold.

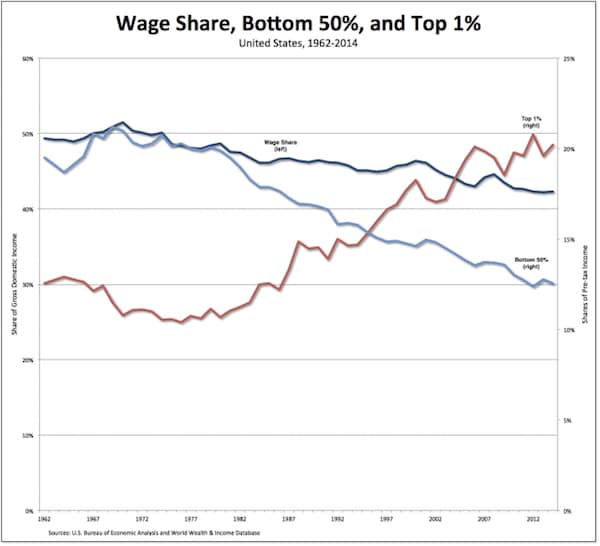

The problem is, as is clear from the chart at the top of the post, the American working-class has lost out under a long series of both Republican and Democratic administrations. Neither party—conservative or liberal—has reflected the interests of working-class Americans in recent decades.

For example, between 1970 and 2014, the share of wages in national income plummeted from 51.5 percent to 42.3 percent.* As a result, the share of income going to the bottom 50 percent of Americans has literally collapsed, falling from 17.8 percent in 1970 to only 12.5 percent in 2014.

Meanwhile, the top 1 percent has enjoyed enormous success: its share of pre-tax income has soared in the past four and a half decades, rising from 12.5 percent to over 20 percent.

The problem for the American working-class is that neither party represents its interests—and no new party has emerged, at least on a national level, to take their place. So, working-class voters are left to float, under increasingly precarious economic conditions, in support of politicians from both parties who have pandered to a variety of identities and issues but have done nothing to effectively reverse the insults and injuries inflicted upon the American working-class in recent decades.

That’s what’s the matter with the United States.

*And, remember (as I explained in 2015), the wage share includes the salaries of CEOs and others at the top of the scale, which should rightly be excluded as distributions of the surplus. If they were subtracted, the share going to working-class Americans would have fallen even further.