…must come down.

I’m not referring to karma or the application of Newton’s law of universal gravitation. No, it’s just the way capitalism works.

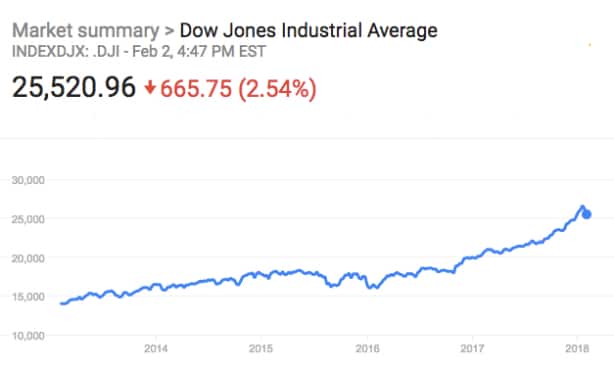

Take the stock market, for example. Last Friday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed down 666 points, or 2.5 percent, its biggest percentage decline since the Brexit turmoil in June 2016 and the steepest point decline since the 2008 financial crisis.

The large decline is really no surprise, since the U.S. stock market—a thoroughly speculative institution within contemporary capitalism—has been on the rise, based on soaring corporate profits, since 2009.

Rising stock values are related to corporate profits in two ways: First, they are bets on corporate profits, in the sense that stock speculators expect future prices to track the rate at which corporations are able to extract surplus and realize profits from their workers. Second, the profits themselves are distributed by corporations—internally, to buy back their own stocks, and to wealthy individuals (such as CEOs and recipients of dividends), who are in the position to capture their own portion of the surplus and use it to engage in speculative stock-market purchases.

So, stock-market indices went up—and then, last week, they came down.

No one knows why the stock market plummeted, although there are many stories out there. One of them is the jobs report—indicating 200 thousand new jobs in January and an increase in workers’ wages—and the risk that the profit rate might fall.

That’s another one of those up-down features of capitalism. And every time the profit rate falls, as if like clockwork, a recession or depression is just around the corner. Corporations cut back spending, workers are laid off, and then—perhaps, always maybe—the conditions are created for another economic upturn.

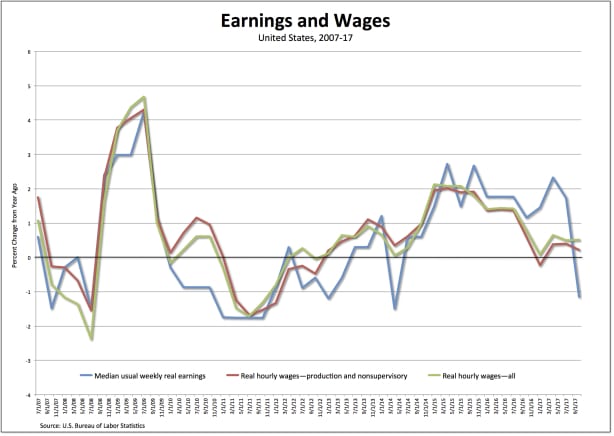

Here’s what’s interesting: while average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls once again increased (in January by 9 cents to $26.74, following an 11-cent gain in December, and thus, over the year, by 75 cents, or 2.9 percent), average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees increased by only 3 cents (to $22.34, or 2.4 percent on an annual basis) in January—in both cases, just a bit more than the rate of inflation. And by another measure—real weekly earnings—wages actually fell (by 1.1 percent) during the last quarter of 2017.

So, there’s no clear indication that workers’ wages are finally ready to take off (as mainstream economists and business commentators keep promising) or that they’ll make a large dent in corporate profits.

In fact, as is clear from the chart above, workers’ wages continue to lag far behind increases in productivity—literally no change compared to an increase of almost 9 percent, respectively, since 2009.

Still, even the threat that workers’ wages might rise seems to have spooked the stock market, which tells us something else about capitalism: the members of the small group who, in terms of wealth and power, stand above the rest by benefitting from and betting on corporate profits are themselves no more than uncertain followers of the herd.

Up and then down again. . .