Ambassador Nikki Haley’s decision last week to withdraw the United States from the United Nations Human Rights Council is remarkable. The United States is the first nation in the body’s 12-year history to voluntarily remove itself from membership in the council while serving as a member.

Some have alleged that the timing of Haley’s decision is conspicuous. “The move,” read the second paragraph of a CNN report on Haley’s decision, “came down one day after the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights slammed the separation of children from their parents at the US-Mexico border as ‘unconscionable.’”

It’s true the Trump administration has been threatening to leave the Council for much of the past year. And the condemnation of the administration’s policy of separating children from their parents on the border was perhaps the last straw.

However, in my view, at least as important was a report last month by the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, on his mission to the United States late last year.*

Alston’s critique of the economic situation in the United States could not be more pointed.

Alston’s critique of the economic situation in the United States could not be more pointed.

The United States is a land of stark contrasts. It is one of the world’s wealthiest societies, a global leader in many areas, and a land of unsurpassed technological and other forms of innovation. Its corporations are global trendsetters, its civil society is vibrant and sophisticated and its higher education system leads the world. But its immense wealth and expertise stand in shocking contrast with the conditions in which vast numbers of its citizens live.

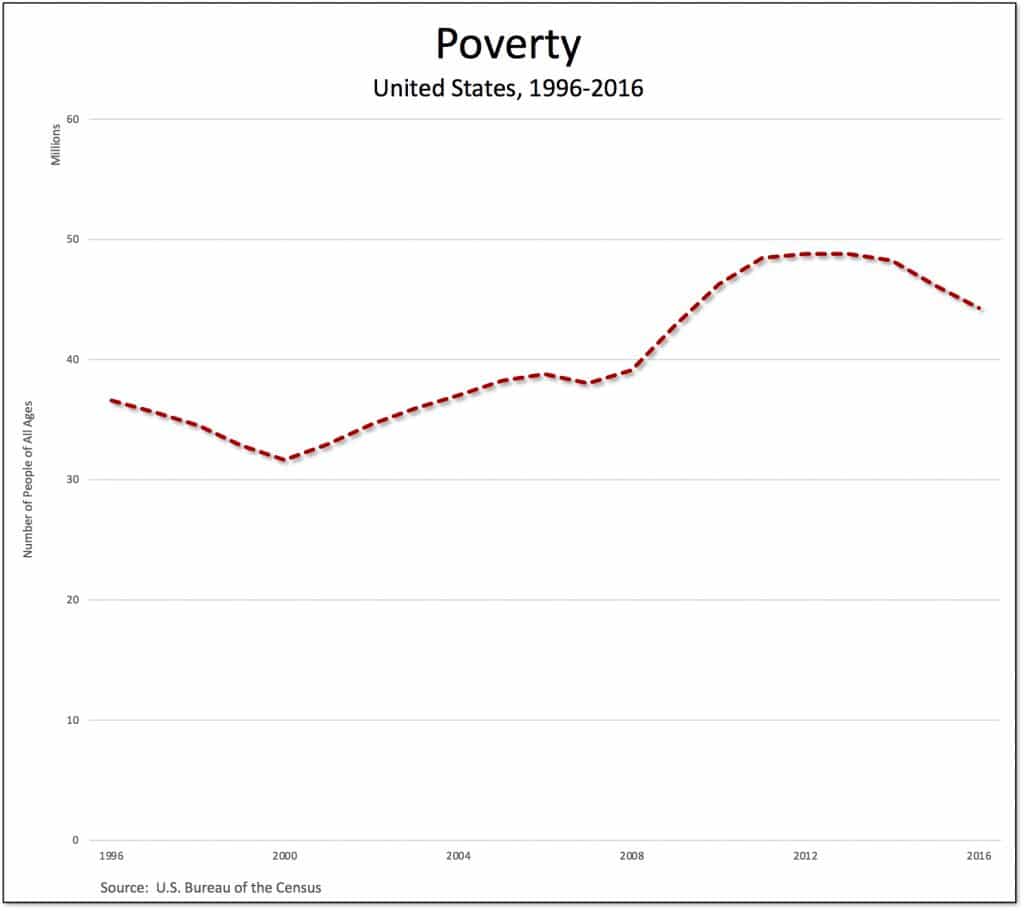

For example, more than 40 million Americans live in poverty, with 18.5 million in extreme poverty and more than 5 million in conditions of absolute poverty.

Then,

The United States has the highest rate of income inequality among Western countries…. The consequences of neglecting poverty and promoting inequality are clear. The United States has one of the highest poverty and inequality levels among the OECD countries….But in 2018 the United States had over 25 per cent of the world’s 2,208 billionaires. There is thus a dramatic contrast between the immense wealth of the few and the squalor and deprivation in which vast numbers of Americans exist.

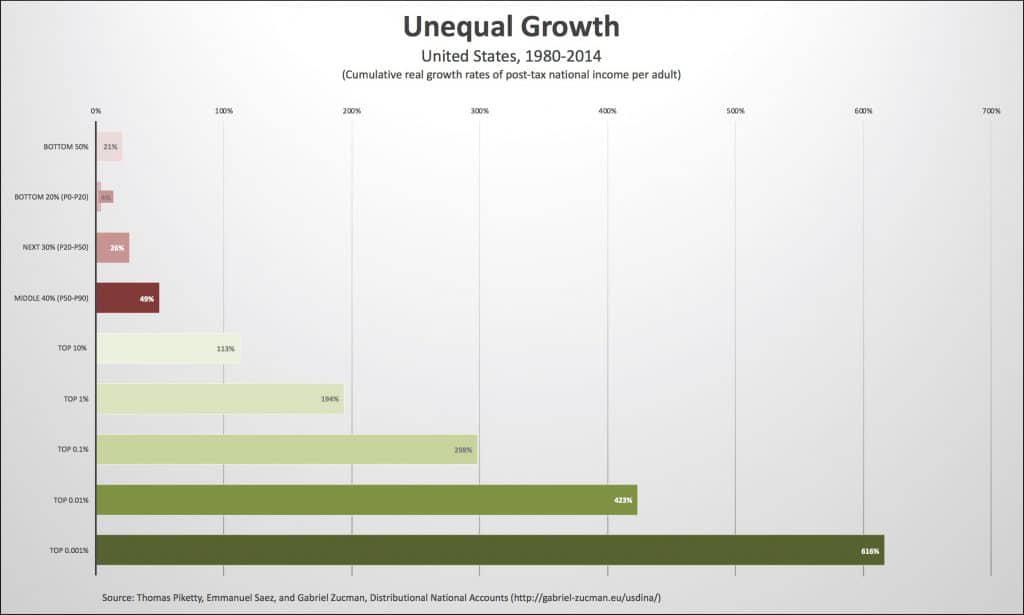

According to data compiled by Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman (pdf), between 1980 and 2014, the incomes of those at the top soared (the green bars in the chart above: 616 percent for the top 0.001 percent, 421 percent for the top 0.01 percent, 298 percent for the top 0.1 percent, and 194 percent for the top 1 percent), while the incomes of those in the bottom 90 percent barely rose (the rose-colored bars: 49 percent for the middle 40 percent and 21 percent for the bottom 50 percent).

Both trends—rising poverty and increasing inequality—have been going on for decades now. But, Alston is clear, the situation is only going to worsen under the current administration:

The new policies: (a) provide unprecedentedly high tax breaks and financial windfalls to the very wealthy and the largest corporations; (b) pay for these partly by reducing welfare benefits for the poor; (c) undertake a radical programme of financial, environmental, health and safety deregulation that eliminates protections mainly benefiting the middle classes and the poor; (d) seek to add over 20 million poor and middle class persons to the ranks of those without health insurance; (e) restrict eligibility for many welfare benefits while increasing the obstacles required to be overcome by those eligible; (f) dramatically increase spending on defence, while rejecting requested improvements in key veterans’ benefits; (g) do not provide adequate additional funding to address an opioid crisis that is decimating parts of the country; and (h) make no effort to tackle the structural racism that keeps a large percentage of non-Whites in poverty and near poverty.

What that means is a deterioration of human rights in the United States, because

International human rights law recognizes a right to education, a right to health care, a right to social protection for those in need and a right to an adequate standard of living.

In other words, according to international law, economic rights are human rights. More specifically, worker rights are human rights—and workers are the ones who are suffering from the growth in poverty and the obscene levels of inequality in the United States. Their rights have been violated for decades now, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, and the prospect looking forward—under Donald Trump and his Republican allies—is even bleaker.

The solution begins with the recognition that economic rights, especially worker rights, are in fact human rights. And the only way to uphold those rights is to radically transform the existing economic institutions, to give workers the right to participate in making the decisions that affect their lives.

Note

* As it turns out, the day after I wrote this post Haley attacked Alston’s report on U.S. poverty:

Haley, the former Republican governor of South Carolina, said she was “deeply disappointed” that the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, had “categorically misstated the progress the United States has made in addressing poverty … in [his] biased reporting”. She added that in her view that “it is patently ridiculous for the United Nations to examine poverty in America.”