In the West, since at least the myth of Gaea, the earth has been seen as something feminine. For ecofeminists, the linkage has had profound, and malign, consequences for our treatment both of nature and of women. More recently, xenofeminists have reconsidered the liberatory possibilities of instrumental technology: whereas for some ecofeminists nature is inviolable, xenofeminists would have us transcend it with the aid of science and technology. In advance of her upcoming course Ecofeminism and Xenofeminism, we sat down with BISR faculty Alyssa Battistoni for an extended discussion of the two tendencies and their differences and points of convergence. Are the twin dominations of nature and women a function of capitalism, or are they rooted in something longer-standing? Is nature an unalloyed good? Can technology dismantle patriarchy? How does gender itself figure in eco- and xenofeminist thought? What does a feminist approach to the problems of climate change look like?

It’s worth beginning by asking: what are ecofeminism and xenofeminism? Are they necessarily opposed, or are there points of intersection?

Ecofeminism is a political and intellectual movement that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s out of a convergence of elements of the anti-nuclear, environmental, and feminist movements. There are various strains of ecofeminism, but in general, ecofeminists point to similarities between the way that both nature and women have been conceptualized and treated in Western thought, often traced to the idea of Cartesian dualism, which sees mind and body as totally distinct—the mind is immaterial reason, while the body is just matter—and which sees the mind as superior and truly human. This dualism in turn structures other dualisms—between culture and nature, reason and emotion, masculine and feminine. Women, ecofeminists argue, are typically associated with the animal body and men with the human capacity to reason. Ecofeminism as a perspective argues that the Western privileging of reason has resulted in the domination and exploitation of nature and of people who are thought of being closer to it. Many ecofeminists have therefore called for women to ally themselves with nature in rejecting these forms of domination in its various forms—including, for some, in the form of Western science and technology.

Xenofeminism is a much more recent invention, at least as terminology—the term comes from the Xenofeminist Manifesto, published a few years ago by the feminist collective Laboria Cuboniks. The manifesto declares xenofeminism to be “vehemently anti-naturalist,” on the grounds that “anyone who’s been deemed ‘unnatural’ in the face of reigning biological norms, anyone who’s experienced injustices wrought in the name of natural order, will realize that the glorification of ‘nature’ has nothing to offer us.” But what they call xenofeminism draws on a longer history of feminist skepticism about nature, which is wary of nature as something that has traditionally been used to justify gender oppression. Nature isn’t something to embrace, but something that people who have been considered “natural,” including but not limited to women, should seek to free themselves from, with the help of science and technology.

So, to give a concrete example, the ecofeminist Maria Mies argues that “reproductive technology alienates both men and women from their bodies” and therefore from nature, which in her view is a bad thing; xenofeminists, meanwhile, proudly declare themselves in favor of alienation, and see reproductive technologies as liberatory.

That said, I don’t think they have to be opposed. I’m interested in working towards an eco-xeno-feminism (xecofeminism?): an ecofeminism that’s strange, monstrous, and alien, that’s against “Nature” in the sense of the given order of things but interested in nature as it actually exists in the world.

Patriarchy long predates capitalism; but the rigorous technological exploitation of nature? and the inequality of technological outcomes? seems quite entwined, both conceptually and as a historical fact, with the capitalist mode of production. Is ecofeminism necessarily anti-capitalist? Or, from an ecofeminist perspective, is capitalism merely a kind of intensification of patterns of domination established at the very origins of agricultural civilization (if not earlier)?

I think most ecofeminists are anti-capitalist in some sense, though they might not describe their position in exactly those terms—for many ecofeminists, the domination of women and nature is primary, and capitalism is simply one form this domination takes. Most ecofeminists are critical of industrialization, at the very least, and some would suggest that the origins of the domination of nature go back even further. But to the extent that capitalism intensifies and relies on the domination and exploitation of nature—which it does, whether in intensifying the production of cash crops at the expense of soil fertility or extracting and burning huge amounts of fossil fuels to move goods around the globe—ecofeminists are anti-capitalist. Because ecofeminism has such a deep analysis of the origins of patriarchy, I think it’s harder to reconcile with capitalism than some other strains of feminism are—though you can see what we might call a lifestyle ecofeminism that embraces naturalness and sustainability (I’m thinking here of things like goop, wellness culture, or the “witch kits” that Sephora tried to sell).

But if ecofeminists are critical of capitalism they are often also wary of socialism; in particular, they tend to be critical of twentieth-century socialism for its reliance on industrial production, and of twentieth-century Marxism for suggesting that humans will be liberated through the domination of nature. Many of these critiques are valid and important! But sometimes ecofeminist critiques blur the distinction between capitalism and socialism into a critique of “industrialism” or “modernity” per se.

How, in the xenofeminist conception, can technology and production be used non-oppressively and to equal benefit?

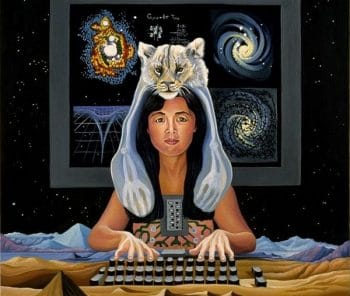

Xenofeminists suggest that technology itself isn’t inherently a source of domination; rather, the problem is that technology has been put to use in service of capitalist exploitation and patriarchal domination. This follows in a long tradition of radical thought that calls for seizing tools developed under conditions of patriarchy and / or capitalism and putting them to use for the benefit of all. If Marx calls for seizing the means of production, xenofeminists might call for seizing the means of reproduction too. For someone like Shulamith Firestone, that means separating the genitalia someone is born with from whether they then can, or have to, become pregnant and have children. She thinks that many critics of technology are beating up the wrong bush: “Radicals,” she says, “rather than breast-beating about the immorality of scientific research, could be much more effective by concentrating their full energies on demands for control of scientific discoveries by and for the people. For, like atomic energy, fertility control, artificial reproduction, cybernation, in themselves, are liberating—unless they are improperly used.” She thinks that putting these technologies to use in the right way means, say, developing artificial wombs so that being born with a uterus doesn’t determine your reproductive fate. For someone like Donna Haraway, it might mean using biotechnology to genetically modify ourselves or other organisms out of interest, pleasure, or curiosity instead of letting corporations patent genes and sell “nature itself” as a commodity.

Xenofeminists suggest that technology itself isn’t inherently a source of domination; rather, the problem is that technology has been put to use in service of capitalist exploitation and patriarchal domination. This follows in a long tradition of radical thought that calls for seizing tools developed under conditions of patriarchy and / or capitalism and putting them to use for the benefit of all. If Marx calls for seizing the means of production, xenofeminists might call for seizing the means of reproduction too. For someone like Shulamith Firestone, that means separating the genitalia someone is born with from whether they then can, or have to, become pregnant and have children. She thinks that many critics of technology are beating up the wrong bush: “Radicals,” she says, “rather than breast-beating about the immorality of scientific research, could be much more effective by concentrating their full energies on demands for control of scientific discoveries by and for the people. For, like atomic energy, fertility control, artificial reproduction, cybernation, in themselves, are liberating—unless they are improperly used.” She thinks that putting these technologies to use in the right way means, say, developing artificial wombs so that being born with a uterus doesn’t determine your reproductive fate. For someone like Donna Haraway, it might mean using biotechnology to genetically modify ourselves or other organisms out of interest, pleasure, or curiosity instead of letting corporations patent genes and sell “nature itself” as a commodity.

Why should nature be privileged as “good”? Doesn’t the linkage of nature and the “female”? beyond the empirical fact that women suffer disproportionately the effects of environmental degradation? reinforce sexist, constructed ideas of a female essence and capability?

I personally don’t think nature should be privileged as good! The tendency to link nature and the “feminine” can definitely reinforce ideas of some female essence—a way that women “just are”—which in turn reinforces a sense that they will always be that way, and that any efforts to change gender relations are futile. Social and political thought has used nature as a model for moral instruction for centuries with different aims—some thinkers see nature as a good, others as something to be escaped—but I think that appeals to nature are very rarely liberatory. They’re much more likely to be deployed by someone like Jordan Peterson, who tells us that human society should be hierarchical because lobsters are hierarchical—that everyone should stay in their place and stop trying to fight it.

But ecofeminists remind us that humans can’t simply shape nature to our purposes, and that nature in fact has its own purposes. Nature, whether in our own bodies or the wider world, is something we have to live with—we can’t liberate ourselves from our bodies altogether, and we can’t shape the world to our making. Ecofeminists remind us that nature has a mind of its own, as it were, and that we should respect nature’s autonomy.

It’s also important to remember that nature is a lot weirder than the Jordan Petersons of the world seem to think. There are not many nuclear families out in nature! Instead, there are a lot of creatures that are sex-changing, mate-eating, asexually-spawning, and so on. That doesn’t mean that those creature should be models either; the point is that nature doesn’t just give us a template for how to be, and we shouldn’t expect it to.

Frankly, I think we should denaturalize nature itself—we should get beyond the idea that the natural order is fixed and permanent, because in fact nature is changing all the time, certainly in relation to human activity but also in relation to things that have nothing to do with us.

So my own anti-naturalism more of a reaction to the idea of Nature and how it’s deployed. Ideally I don’t think we should try to assign nature a moral valence at all—I’d rather think about “nature” as it actually is in the world than use it to fashion a story about how things should be.

A component of xenofeminism seems to be gender-abolitionism. How do non-binary ideas of gender, or even its transcendence, comport with ecofeminist thought?

Xenofeminists are absolutely interested in abolishing the system of gender oppression, which doesn’t mean flattening gender expression into some monotone—to the contrary, the Manifesto says, “let a thousand sexes bloom!” Abolishing gender in this sense means abolishing social structures that assign people roles based on their body parts and/or gender identity. From a Marxist perspective, for example, you might recognize that gender structures what kinds of work people do (cleaning houses or working in a factory, being a midwife or a physicist) and how that work is valued both socially and economically.

By contrast, a lot of ecofeminism comes out of the second-wave tradition, which often relies on a binary idea of gender and a more biologically essentialist conception of womanhood. Some ecofeminists accept the idea of gender dualism, and simply flip the poles, arguing that we should affirm feminine virtues instead of masculine ones. The most extreme versions make comparisons between human reproductive capacities and the earth, suggesting that the capacity to create life makes people with wombs—in this discourse, women—closer to the earth, or that (cis) women are naturally more nurturing and caring. Books like Mary Daly’s Gyn/Ecology (which we are not reading in the course) are extremely binary in their view of gender, and are certainly not interested in transcending that binary—they are celebrating and in many ways reinforcing what they think it means to be a woman.

But I don’t think that has to be the case; it’s possible to be an ecofeminist without reinforcing gender dualism. I actually think ecofeminism often gets a bad rap for essentialism—at some point, the perception that ecofeminism was all goddesses and earth mothers took over, and people started distancing themselves from ecofeminism as a descriptor. (Frankly, I think the “uncoolness” of ecofeminism also has to do with the very things it seeks to address—i.e., the idea that environmentalism and feminism are silly and not politically serious.) I think there are strains of ecofeminism that are much more critical and expansive. Like other feminisms, contemporary ecofeminism engages with intersectionality, postcoloniality, indigeneity, queerness, and other thinking that complicates the idea of “womanhood.” These kinds of ecofeminism can help us think through ways of abolishing gender in our relationship to the earth.

Here, again, it’s important to remember that we can abolish gender as way of structuring society without abolishing things like bodily experience or difference. So, to use a somewhat stylized example, we should reject the idea that only people born with a womb are women, and that they therefore have a special connection to the earth via life-giving capacities, or are more likely to nurture the earth than destroy it. But I don’t have a problem with people feeling that having a womb makes them feel close to the earth, if anyone who wanted to could have a womb, and people with wombs could do things other than making babies, and if we recognized that there are a lot of ways to be close to the earth through use of our bodies, whatever parts we might have (and however technologically mediated they might be).

In your course Ecofeminism and Xenofeminism, you’ll work with a set of thinkers? for example, Vandana Shiva and Shulamith Firestone? who seem, at a glance, worlds apart. And yet, both address directly all-too-timely issues surrounding ecology and climate change. What does a specifically feminist approach? with all the diversity that such a moniker encompasses? bring to debates about and analyses of climate?

Yes! We are going to read a wide array of thinkers, and they will definitely disagree on some things—from what the source of the climate crisis is to what ought to be done in response. Firestone, for example, makes an argument in favor of something that might be called geoengineering, while Shiva would say that technology got us into this mess and can’t get us out of it. (And some of them, like the indigenous thinker Winona LaDuke, probably wouldn’t describe themselves as ecofeminists or xenofeminists at all.)

But all of the thinkers we’ll read can help us think about the relationship between gender, nature, and technology; about how we relate to other humans and to the earth we live on and with, and about how we could; about how the benefits and harms of fossil-fueled growth are distributed unevenly—across gender, race, class, but also across species, space, and time.

You can’t fully understand climate change without understanding capitalism, and you can’t understand capitalism without understanding the place of nature in it. Feminist perspectives help us see how nature has been systematically devalued, taken for granted, taken for free, treated as externalities. Eco-socialist-feminism reminds us that both social and ecological reproduction is central to how capitalism works; xenofeminism reminds us that we shouldn’t naturalize or valorize reproduction as an inherent good.

So read together, and perhaps at times against one another, these thinkers can help us imagine a society and economy that treats the earth with care and respect—traits I certainly hope aren’t specific to women!—while at the same time recognizing the potential of science and technology and human knowledge (not necessarily derived from Western epistemologies!) to not simply dominate nature for human purposes, but to understand the world we live in and shape the world we want.