Considering his work as a whole, Marx had little to say directly about women’s oppression or the relationship between patriarchy and capitalism.1 And some of what he had to say was, well, misguided. Yet Marxist feminists have drawn on his thought to create a distinctive approach to understanding these issues.2

Marxist feminists begin, where Marx does, with collective labor. Human beings must organize labor socially in order to produce what we need to survive; how socially necessary labor is organized, in turn, shapes the organization of all of social life. In The German Ideology, Marx articulated this foundational starting point:

The fact is, therefore, that definite individuals who are productively active in a definite way enter into these definite social and political relations. Empirical observation must in each separate instance bring out empirically, and without any mystification and speculation, the connection of the social and political structure with production. The social structure and the State are continually evolving out of the life-process of definite individuals, but of individuals, not as they may appear in their own or other people’s imagination, but as they actually are; i.e. as they act, produce materially, and hence as they work under definite material limits, presuppositions and conditions independent of their will. (MECW 5:37)

When Marx refers to individuals who are productively active in a definite way, he is thinking primarily about the production of material goods. Marxist feminists expand the notion of socially necessary labor to include that part of collective labor that meets individual needs for sustenance and daily renewal as well as birthing and rearing the next generation.

The term “social reproduction” has been developed to refer to this labor.3 By social reproduction is meant the activities and attitudes, behaviors and emotions, responsibilities and relationships directly involved in maintaining life on a daily basis and inter-generationally.

Social reproduction involves various kinds of socially necessary work—mental, physical and emotional—aimed at meeting historically and socially, as well as biologically, defined needs and, through meeting these needs, maintaining and reproducing the population.

Among other things, social reproduction includes how food, clothing and shelter are made available for immediate consumption, how the maintenance and socialization of children is accomplished, how care of the elderly and infirm is provided, how adults receive social and emotional support, and how sexuality is experienced. From this starting point, we can see how gender and gender relations—such as a gender division of labor—are social, historical constructs, embedded in structures of social reproduction.

Actually existing capitalist societies each have their own histories and trajectories of change, and gender relations are structured across a diverse terrain. While recognizing this complexity, socialist-feminists have drawn on Marx’s work to analyze how patriarchal relations work in capitalist societies. By going back to Marx’s texts, I want to highlight some aspects of this socialist-feminist theoretical framework.

Social Reproduction and Gendered Division of Labor

That we speak of production on the one hand and social reproduction on the other is, in part, an artifact of both the (masculinist) development of Marxist thought and the nature of the capitalist mode of production. In capitalism, the work done in households, although crucial to the reproduction of human beings, is separated off from the production and circulation of commodities. In comparison, with the exception of slavery, in pre-capitalist class societies, households organized through marriage and kinship were the basic unit for organizing the production of material goods as well as human care.

As Marx pointed out, in capitalist production commodities (including commodified services) are both use values and exchange values. (MECW 35:45-46) That is, they meet a need (otherwise there would be no point in making them); but they are not produced in order to meet needs. Rather, they are produced to generate surplus value—or profit.

From the point of view of the production of use values, waged and unwaged labor form a unified process which has, as its end result, the reproduction of human beings. The separation of what is, from the point of view of production of use values, an integrated process into two different types of labor (commodified and uncommodified) is a result of capitalist class relations of production, not a universal fact of human social life.

This separation parallels the emergence of divisions between the public and private spheres, between family and work, between the state and the economy. These are also a hallmark of capitalist societies. These double separations—economy/household and economy/state—have shaped the history of gender relations and women’s struggles to change them within capitalist societies.

Until now, all known systems of social reproduction have been based on a gendered division of labor (albeit sometimes quite rigid, at other times more flexible). Although this pattern appears to be mandated biologically—by the physical requirements of procreation and the needs of infants—the distribution of the work of social reproduction among families, communities, markets, states and between women and men has varied historically. This variation can be analyzed, at least in part, as the outcome of struggles around class and gender, struggles that are often about sexuality and emotional relations as well as political power and economic resources.

In societies that preceded capitalism, property rights were vested in male household heads and formed the basis of patriarchal authority—literally the rule of the fathers. For capitalist class relations to emerge, this system of property rights had to be overthrown. The forcible legal and extra-legal processes through which men were deprived of their property and turned into wage laborers threatened to undermine this patriarchal system—at least for the working class. Observing the extreme exploitation of women and children in the 19th century factories, Marx argued in Capital, Vol. I:

However terrible and disgusting the dissolution, under the capitalist system, of the old family ties may appear, nevertheless, modern industry, by assigning as it does an important part in the process of production, outside the domestic sphere, to women, to young persons and to children of both sexes, creates a new economic foundation for a higher form of the family and of the relations between the sexes…Moreover, it is obvious that the fact of the collective working group being composed of individuals of both sexes and all ages, must necessarily, under suitable conditions, become a source of humane development; although in its spontaneously developed, brutal, capitalistic form, where the labourer exists for the process of production, and not the process of production for the labourer, that fact is a pestiferous source of corruption and slavery. (MECW vol. 35:492-493)

Although Marx was vague about how this higher form of family and relations between the sexes would be constituted, he was quite clear in his critique of the bourgeois family where male property owners continued to hold sway over their wives and children.

“But you communists would introduce community of women, screams the whole bourgeoisie in chorus. The bourgeois sees in his wife a mere instrument of production. He hears that the instruments of production are to be exploited in common, and, naturally can come to no other conclusion than that the lot of being common to all will likewise fall to the women. He has not even a suspicion that the real point aimed at is to do away with the status of women as mere instruments of production.” (MECW 6: 502)

Marx insisted that there was no “natural” or “transhistorical” family form. Thus, he argued, in Capital Vol. I, “It is, of course, just as absurd to hold the Teutonic-Christian form of the family to be absolute and final as it would be to apply that character to the ancient Roman, the ancient Greek, or the Eastern forms which, moreover, taken together form a series in historical development.” (MECW 35:492).

While Marx never developed his analysis of this historical evolution, his notes on the family in pre-capitalist societies point to a more dialectical approach than that taken by Engels, for whom the introduction of private property determines the “world historical defeat of the female sex.” For example, Marx points to the simultaneous emergence of hierarchical rank and men’s collective control over women (as captives/slaves) in clan societies prior to the development of private property. (Brown 2013)

Marx was in one sense right about the long-run possibilities for challenging patriarchal family relations that inhere in women’s access to wage labor. However, his critique of exploitative employment, while exposing the destruction of women’s and children’s health and well-being, also drew on ideals of feminine virtue that were central to the “separate spheres” gender ideology of his age—thus the reference to the “corrupting” influence of factory work under capitalism.4

Marx tended to conflate physical and moral health in his scathing critiques of 19th century working conditions, and reserved special condemnation for instances where gender differences were undermined, as in his selection of this quote from a commission report in Capital Vol. I:

The greatest evil of the system that employs young girls on this sort of work consists in this…They become rough, foul-mouthed boys, before Nature has taught them that they are women…they learn to treat all feelings of decency and of shame with contempt…Their heavy day’s work at length completed, they put on better clothes and accompany the men to the public houses. (MECW 35: 467)

An even more important problem with Marx’s analysis is that he does not fully incorporate the sheer amount of caring labor required for human survival, and insofar as he does pay attention tends to assume that it is naturally women’s work. Marx occasionally indicates the importance of women’s domestic work, as, for example, in Capital, Vol. I describing the disastrous consequences for the family (and the increased profit for the employer) in the employment of women and children alongside men:

Compulsory work for the capitalist usurped the place, not only of the children’s play, but also of free labour at home within moderate limits for the support of the family. The value of labour-power was determined, not only by the labour time necessary to maintain the individual adult labourer but also by that necessary to maintain his family. Machinery, by throwing every member of that family on to the labour-market, spreads the value of the man’s labour-power over his whole family. (MECW 35:398-399)

Marx goes on to argue that because the family must rely more on purchasing commodities rather than domestic work, “[t]he cost of keeping the family increases, and balances the greater income.” Increasing the number of wage earners does not raise but lowers the family’s standard of living, because “economy and judgment in the consumption and preparation of the means of subsistence becomes impossible.” In other words, the value inherent in women’s domestic skills is lost.

During the U.S. Civil War, which disrupted the cotton trade, textile workers in England suffered massive layoffs. Here, Marx argues, the women operatives “had time to cook. Unfortunately the acquisition of the art occurred at a time when they had nothing to cook. But from this we see how capital, for the purposes of its self-expansion, has usurped the labour necessary in the home of the family.” (MECW 35:399).

Marx thus identified a central contradiction of capitalism—that although capital depends on the reproduction of labor power, the demand for profit threatens to undermine the reproduction of laborers themselves. Marx captured this conundrum in his famous ironic comment in Capital Vol. I: “The maintenance and reproduction of the working-class is, and must ever be, a necessary condition to the reproduction of capital. But the capitalist may safely leave its fulfillment to the labourer’s instincts of self-preservation and of propagation.” (MECW 35:572).

Labor power differs in a fundamental way from other factors of production. The capitalist who invests in machinery can be reasonably sure to get the fruits of his investment. Indeed, as a rule, capitalists must invest to raise productivity in order to cut costs and compete. In contrast, the capitalist has no hold over the children of his current employees and so is reluctant to pay a wage that can support them. There is thus a tendency toward pushing wages below the bare minimum:

In the chapters on the production of surplus-value it was constantly pre-supposed that wages are at least equal to the value of labour-power. Forcible reduction of wages below this value plays, however, in practice too important a part, for us not to pause upon it for a moment. It, in fact, transforms, within certain limits, the labourer’s necessary consumption-fund into a fund for the accumulation of capital …If labourers could live on air they could not be bought at any price. The zero of their cost is therefore a limit in a mathematical sense, always beyond reach, although we can always approximate more and more nearly to it. The constant tendency of capital is to force the cost of labour back towards zero. (Capital Vol. I, MECW 35:595-596)

From this perspective, the capacity of the working class to reproduce itself depends on the working class itself—on the level and extent of class struggle. Through struggle over the length of the working day, over wages, over the conditions of work, over the extent of the welfare state and other public services, working-class people have wrenched from capitalist employers the means to care for themselves and their children.

At the same time, the forms these struggles took—how working-class men and women defined their goals, organized their forces, developed their strategies—were shaped by institutionalized relations of power and privilege formed around race, gender, sexuality and nationality. In particular, working-class women’s responsibilities for caregiving, and the conditions under which they do this work, have often disadvantaged them in relation to men within both informal and formal arenas of political contestation and decision-making.

On the other hand, women find a ground for respect, authority and power in their care responsibilities. And where women cooperate across households in order to accomplish their work in social reproduction, they create the social basis for collective action. Women’s location in the labor of social reproduction, then, is a resource for resistance as well as a source of disempowerment.

By undermining older forms of individual patriarchal control over women’s labor within family households, capitalist expansion has opened up possibilities for women’s political self-organization—but the organization of social reproduction in a capitalist economy where millions are, from the point of view of capitalist employers, nothing more than a “surplus population,” constitutes the basis for new forms of women’s oppression.

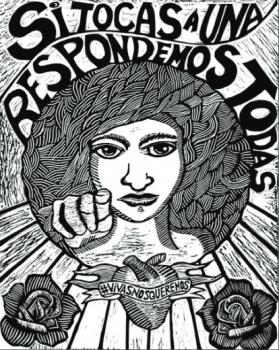

“If you touch one, we will all respond.” A graphic by Mujeres Grabando Resistencia for a campaign to defend women against feminicide.

Some feminists have named this a shift from private to public patriarchy, because it is based in the first instance on men’s collective access to public power rather than on their direct control over household members through property ownership. The question remains, however, why are men able to sustain greater access to public power, given that bourgeois democracy at first in principle and, through decades of feminist struggle eventually in fact, confers equal citizen rights on men and women?

Compelling answers to this question have been developed by feminists who start from the observation that discourses of gender difference are central to the constitution and legitimation of political power.5 Although discourses of gender difference certainly have an effect, from a Marxist feminist standpoint, we would add that ideas do not sustain themselves without some grounding in everyday experience.

This was of course one of Marx’s great insights when describing the “fetishism of commodities.” That relationships between people come to be seen as relationships between things is a reflection of the wage relation in commodity production. This is not a “false consciousness” in the sense of ideas imposed by cultural and social forces; rather, it is a worldview that expresses, or is consonant with, actual experience under the relations imposed by the commodity form.

In the same way, to understand how male domination sustains itself in any given moment, we have to look for the underlying social relations that confer a logic on, make sensible and even productive, discourses of gender difference.

The resistance of capitalist employers to investing in the reproduction of labor power, competition among workers, the individualizing pressures of the wage form itself, all push in the direction of privatizing rather than socializing caregiving work. But so long as caregiving remains a private responsibility of households whose members must engage in substantial hours of both waged and unwaged labor, the gender division of labor will retain a compelling logic.

Of course, individual and family survival strategies based in a gender division of labor are not simply the outcome of rational responses by men and women to material difficulties. They also reflect women’s and men’s interests and desires which are shaped socially and culturally as well as economically.6

Class Relations and Social Reproduction

Three other features of the capitalist system that Marx identified are helpful to us in thinking about how social reproduction—and the gender division of labor within it—have come to be organized and changed over time.

First is the drive toward commodification that arises from capitalist competition and the search for new arenas for profit-making. Here again, we see the two-sided nature of capitalist expansion—in enabling challenges to patriarchal forms, and at the same time limiting what those challenges can accomplish.

As capitalism penetrates all areas of human activity, use values are turned into commodities—things to be bought and sold rather than given, bartered or produced for one’s own use. The conversion of use values into exchange values (commodities) ties people more firmly to the capitalist economy, because in order to consume one has to earn.

On the other hand, ever-expanding possibilities for consumption allow and encourage new forms of individual identification and self-expression. As Rosemary Hennessy points out, in the early 20th century:

(S)tructural changes in capitalist production that involved technological developments, the mechanization and consequent deskilling of work, the production boom brought on by technological efficiency, the opening of new consumer markets, and the eventual development of a widespread consumer culture…displaced unmet needs into new desires and offered the promise of compensatory pleasure, or a least the promise of pleasure in the form of commodity consumption…This process took place on multiple fronts and involved the formation of newly desiring subjects, forms of agency, intensities of sensation, and economies of pleasure that were consistent with the requirements of a more mobile workforce and a growing consumer culture. (Hennessy 2000: 99)

The spread of consumerism, wage labor, urbanization, the decline of small businesses and the related rise of new professions whose practitioners were a driving force toward state regulation of bodies (e.g. medicine, public health, social work, psychology) all laid the basis for a reorganization of sexuality and family life, particularly in the middle class. Older patriarchal norms of motherhood, marriage and sexuality were overturned, but replaced by a heteronormative regime that re-inscribed the gender division of labor.7

By the end of the 20th century, intensified commodification, as Alan Sears argues, had not only generated the spaces of open lesbian and gay existence, but also consolidated gay visibility around a class and race specific identity that relies predominantly on the capacity to consume. (Sears 2005: 92-112)

The more life becomes organized around the production and consumption of commodities, the more people are encouraged/allowed to regard every aspect of their humanity as a potential for making money. The logic of possessive individualism and the commodification of labor power that is its foundation creates a powerful drive toward regarding affection, sexuality, and even biological reproductive capacities as commodities that can be bought and sold.

As Marx and Engels wrote in The Communist Manifesto, describing the spread of capitalist social relations: “All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify.” (MECW 6: 487)

The infinitely repeated counterposition of modernity and tradition, culture and nature, sacred and profane in contemporary political discourses revolves around the dualism between exchange value and use value—between that which can or should be sold and that which cannot or should not be.

There is no way out of this dualism, and therefore out of the debate, so long as the conditions under which people possess their bodily capacities are governed by the scarcity and insecurity of life under capitalism. In a context of coercion, which is always present so long as people are separated from their means of survival, it is difficult to distinguish labor that is meaningful and freely chosen from that which is not.

The commodification of procreation (not all of which requires new reproductive technologies) offers new fields for profit-making, while also expanding access to biological parenthood for new groups: gay men (e.g. egg “donation”/surrogacy), lesbians (e.g. sperm banks) and infertile heterosexual couples (e.g. surrogacy, in vitro fertilization). Commodification of procreation undermines ideals of motherhood as a naturally mandated identity and challenges religious and biologically based legitimations of patriarchal family relations, replacing them with contractual norms of choice and consent.

At the same time, commodification of procreation also opens up new possibilities for generating profit through the exploitation of women’s reproductive capacities (e.g. in surrogate pregnancy and egg donation), while defining women’s access to these new forms of earning income to be their right as “free” wage earners.8

A second feature of capitalist production relations that shapes the organization of social reproduction and the gender division of labor is capitalist control over the work process. As Marx points out, insofar as workers control important aspects of the production process they have a basis for resistance; therefore, capitalist employers seek to minimize workers’ control through deskilling and through supervision.

In Capital Vol. I, Marx distinguishes between the coordination required for a complex cooperative labor process and the very different work of control necessitated by the capitalist character of that process, which creates an “unavoidable antagonism between the exploiter and the living and labouring raw material he exploits.”(MECW 35: 336).

He goes on to say,

If then the control of the capitalist is in substance two-fold by reason of the two-fold nature of the process of production itself—which on the one hand is a social process for producing use values, on the other a process for creating surplus value—in form that control is despotic.’ (MECW 35: 337)

Managerial strategies for controlling labor create, incorporate and reproduce relations of power and privilege organized by race, gender, nationality and sexuality (Burawoy 1979; Munoz 2008). Processes of gendering, racializing, and sexualizing bodies and identities, embedded in capitalist management, take up and reinforce hegemonic constructions of gender dualism that are central to the gendered division of labor in social reproduction. At the same time, strategies of working class resistance to managerial power at the workplace and in the broader society also reflect relations of power and privilege organized by race, gender, sexuality, etc. and may constrain management in ways that benefit some workers at the expense of others. For example, local labor markets, and therefore the wages of different groups of workers, are shaped by political processes and not only economic ones.

The consequence of workers’ loss of control over the ways in which labor is coordinated—and the capitalist drive to extract as much surplus labor as possible—is that the full range of human needs cannot be incorporated into decisions about how production is organized.

In no capitalist society is production organized to take into account, to actively support, and to provide for, the socially necessary labor of care. This work is extensive, highly skilled and labor intensive, even though it is often thought of as unskilled and inherent to feminine nature. Even the most “family friendly” welfare state regimes, such as Sweden, do not intrude substantially on private firms’ employment policies.

A third feature of capitalism is that exploitation takes place through the free exchange of the wage contract, and therefore requires the separation of political and economic power. One of the most important shifts in the organization of social reproduction in capitalist societies over the past century has been the emergence of the welfare state—the expansion of public (government) responsibility for education, healthcare, and childrearing, as well as increased (and often oppressive) state regulation of families, especially those in the vulnerable parts of the working class (e.g. immigrants, oppressed racial/ethnic groups, the poor, single mothers).

Although it is tempting to understand these developments as state managers acting in the longterm interests of the capitalist class—stepping in to guarantee the reproduction of the labor force when the capitalist employers will not—we might instead follow Marx’s lead in focusing our attention on the self-organization of the working class.

In Capital Vol. I, describing the victory that enforceable legal limits on the working day represented, Marx sarcastically describes the “conversion” of factory owners and their ideologues to the ideal of regulation following their defeat at the hands of the working class:

The masters from whom the legal limitation and regulation had been wrung step by step after a civil war of half a century, themselves referred ostentatiously to the contrast with the branches of exploitation still ‘free'[of regulation]. The Pharisees of ‘political economy’ now proclaimed the discernment of the necessity of a legally fixed working-day as a characteristic new discovery of their ‘science.’ (MECW 35: 300)

The extent and form of government expansion into social reproduction is the outcome of reform struggles in which middle-class and working-class men and women, not only capitalist employers and state managers, played important roles. As products of struggle, state policies reflect the level and purposes of women’s political self-organization but also the different resources and power available to women and men in different classes and racial/ethnic groups.

Moreover, the terrain on which these groups have engaged is hardly neutral. Developments in the capitalist economy provided political openings and political resources—for example, by drawing women into wage labor—but capitalist class interests also placed constraints on what could be won.

These constraints have been exercised mainly in two ways. First, especially in the liberal market economies, capitalist employers have consistently—and for the most part successfully—resisted government intrusions on their business practices and significant taxation of their profits. More fundamentally, state managers and legislators are ultimately dependent on economic growth and prosperity, which in turn is controlled by capitalist investors.9

By acknowledging these constraints, we can better understand how and why state welfare policies have institutionalized rather than challenged the gender division of labor. For example, in the early 20th century United States, the first government programs to support solo mothers emerged out of a period of intense working-class mobilization and politicization; a broad women’s movement that engaged organized women workers and Black clubwomen, but whose activists and leaders were predominately white and middle-class/upper-class women; and the interventions of new professional groups who offered their expertise to manage, uplift, and assimilate the unruly classes.

In the context of powerful opposition from the employing class and reflecting its constellation of race/class forces, the movement’s predominant discourses sought to legitimize government provision by asserting that paid work was detrimental to good mothering. (Mink 1995; Brenner 2000)

Conclusion

Many contemporary feminist activists and thinkers recognize that gender relations cannot be abstracted from other social relations—of class, race, sexuality, nationality, and so forth. Marx hardly resolved the question of how we might theorize this totality of social relations.10 Still, his analysis of capitalism as a mode of production provides a fruitful starting point for a feminist theory and practice that might not only understand this totality but also engage in movements that can finally transform it.

References

- Armstrong Pat and Hugh Armstrong (1983) “Beyond Sexless Class and Classless Sex: Towards Feminist Marxism” in Studies in Political Economy 10: 7-43.

- Arruzza, Cinzia (2014) “Remarks on Gender,” Viewpoint Magazine, September.

- Barrett, Michele (2014) Women’s Oppression Today: The Marxist-Feminist Encounter, 3rd Edition, London: Verso Press.

- Bank Munoz, Carolina (2008) Transnational Tortillas: Race, Gender, and Shop-Floor Politics in Mexico and the United States, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- Bannerji, Himani (2005) “Building from Marx: Reflections on Race and Class,” Social Justice, 32, 4: 144-161.

- Bhattacharya, Tithi,ed. (2017) Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, London: Pluto Press.

- Block, Fred (1980) “Beyond Relative Autonomy: State Managers as Historical Subjects,” Socialist Register, London: Merlin Press.

- Brenner, Johanna (2000) Women and the Politics of Class, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Brown, Heather A. (2013) Marx on Gender and the Family: A Critical Study, NY: Haymarket Books.

- Burawoy, Michael (1979) Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process Under Monopoly Capitalism, Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Carver, Terrell (1998) The Postmodern Marx, University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Delphy, Christine (1984) Close to Home: A Materialist Analysis of Women’s Oppression, Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Ebert, Teresa L. (2005) “Rematerializing Feminism,” Science & Society, 69, 1:33–55.

- Federici, Sylvia (2004) Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Brooklyn, NY: Automedia.

- Ferguson, Ann (1989) Blood at the Root: Motherhood, Sexuality and Male Dominance, NY: Pandora/Harper Collins.

- Ferguson, Sue (1999) “Building On The Strengths of the Socialist Feminist Tradition,” New Politics, 7, 2: 89-100.

- Gentleman, Amelia (2008) “India Nurtures Business of Surrogate Motherhood,” New York Times (March 10, 2008), 9.

- Gimenez, Martha (2005) “Capitalism and the Oppression of Women: Marx Revisited,” Science & Society, 69, 1: 11–32.

- Hennessy, Rosemary (2000) Profit and Pleasure: Sexual Identities in Late Capitalism, NY: Routledge.

- Hennessy, Rosemary and Chris Ingraham (1997) Materialist Feminism: A Reader in Class, Difference, and Women’s Lives, NY: Routledge.

- Holmstrom, Nancy (2002) The Socialist Feminist Project, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2002.

- Laslett, Barbara and Johanna Brenner (1989) “Gender and Social Reproduction: Historical Perspectives,” Annual Review of Sociology 15: 381-404.

- Marx, Karl (1975) “The German Ideology,” in Marx and Engels Collected Works, Vol. 5, New York: International Publishers.

- Marx, Karl (1976) “The Manifesto of the Communist Party,” in Marx and Engels Collected Works, Vol. 6, New York: International Publishers.

- Marx, Karl (1996) “Capital, Vol. I,” in Marx and Engels Collected Works, Vol. 35, New York: International Publishers.

- Mies, Maria (1986) Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale, London &New York: Zed Books.

- Mink, Gwendolyn (1995) The Wages of Motherhood: Inequality in the Welfare State, 1917-1942, Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press.

- Scott, Joan W. (1986) “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” The American Historical Review, 91, 5: 1053-1075.

- Sears, Alan (2005) “Queer Anti-Capitalism: What’s Left of Lesbian and Gay Liberation?” Science & Society, 65, 1: 92-112.

- Vogel, Lise (2000) “Domestic Labor Revisited,” Science & Society, 64, 2: 151-170.

- Vogel, Lise and Martha Gimenez (eds.) (2005) Marxist-Feminist Thought Today, Special Issue, Science and Society, 65, 1.

Notes

- ↩ I am very grateful to Nancy Holmstrom, Barbara Laslett, and Marcello Musto for their comments on earlier drafts of this essay and Heather Brown for her critical excavation and examination of Marx’s writing on gender and the family.

- ↩ As with any political/intellectual endeavor, Marxist feminism contains a range of approaches. Beyond writers who locate themselves explicitly in Marxist theory, a broader group of socialist feminists draw on Marxist ideas. See, e.g., Nancy Holmstrom (2002); Hennessy (2000); Vogel and Gimenez (2005); Hennessy and Ingraham (1997); Federici (2004); Ferguson (1989), Arruzza (2014).

- ↩ C.f. Brenner (2000); Armstrong and Armstrong (1983); Ferguson (1999); Vogel (2000); Gimenez (2005), Bhattacharya (2017).

- ↩ As Terrell Carver points out, given Marx’s antagonism to Victorian social values, he might also be read here as in line with some strains of Victorian feminism (Carver 1998: 229-230).

- ↩ Cf. Scott (1986); drawing on Marx, Teresa Ebert (2005) offers a critique of the “post-modern turn” in feminism.

- ↩ Debates about the origin and reproduction of the household gender division of labor in capitalism have figured largely in Marxist and socialist feminist theorization of women’s oppression. For a range of approaches, see Delphy (1984); Mies (1986); Costa and James (1975); Barrett (1980); Federici (2004).

- ↩ In addition to Hennessy, see Laslett and Brenner (1989).

- ↩ Like other industries facing government regulation, high wages (or both), the surrogate pregnancy business is going global (Gentleman 2008).

- ↩ For a classic statement of this argument, see Fred Block’s, “Beyond Relative Autonomy: State Managers as Historical Subjects” (1980).

- ↩ For a feminist reading of Marx and theorization of the ensemble of social relations see Himani Bannerji, “Building from Marx: Reflections on Race and Class” (2005), and see also Cinzia Arruzza “Remarks on Gender” (2014).