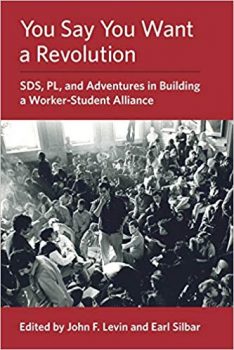

You Say You Want a Revolution: SDS, PL, and Adventures in Building a Worker-Student Alliance, Edited by John F. Levin and Earl Silbar (San Francisco: 1741 Press, 2019), 364 pages, $18.95.

In pop culture versions of 1960s activism, student radicals are often depicted as spoiled upper-class kids rebelling against their privileged parents, engaging in random acts of violence, and despising the nation’s wage-earning majority. In reality, the 100,000 or so youths in the student movement were largely drawn from the lower middle class, and some from the working class; their parents were frequently in general agreement with their children’s politics; the period’s radical activism was much more about leafleting, petitioning, and tabling than about confrontations with the police; and far from rejecting the country’s workers, a significant part of the movement considered finding ways to approach this class a central political issue.

You Say You Want a Revolution: SDS, PL, and Adventures in Building a Worker-Student Alliance, edited by John F. Levin and Earl Silbar.

You Say You Want a Revolution: SDS, PL, and Adventures in Building a Worker-Student Alliance is a useful introduction to the actual experience of many or most of the student activists a half-century ago.

The book’s editors, John F. Levin and Earl Silbar, have brought together reminiscences by 23 former members or associates of the Progressive Labor Party, a Maoist group that for several years was one of the major forces in the 1960s student movement and was probably the best-known advocate of a working-class orientation. With their wide range of styles and perspectives, these little memoirs give a good sense of the period and the issues, but their value is more than historic. As a new generation is being drawn to radical politics, today’s activists may be able to gain useful insights from the experiences of their predecessors.

“Permanent Activists”

The volume’s various writers present many different points of view, but most agree in identifying their former orientation’s greatest strengths and weaknesses.

PL, as both friends and enemies called Progressive Labor, made a number of contributions to the movement: a dramatic defiance in 1963 of the U.S. government’s ban on travel to Cuba, for example, and support for a struggle in late 1968 by students of color at San Francisco State. More generally, the group was instrumental in maintaining a focus on the need to fight racism and to reach out to working people. But most of the writers conclude that PL was inadequate or even harmful in its approach to other issues, as in the mostly male leadership’s downplaying of women’s rights and its open homophobia.

And then there was PL’s sectarianism and its adherence to the Leninist doctrine of democratic centralism.

“Picking up the Banner 1957–1960,” painted by Gely Mikhailovich Korzhev-Chuvelev (1925-). At Russian State Museum. Oil on Canvas, 156 x 290cm.

In practice, democratic centralism turned out to be a form of groupthink and “follow the leadership,” while sectarianism transformed PL from a group that related uncomfortably with others to one that effectively isolated itself from the broader movement. In just a few years the ruling clique in New York moved the party from support for various political forces at home and abroad—including the Black Panthers and the Cuban and Chinese governments—to a global denunciation of almost everything that wasn’t PL.

Despite their criticisms, most of the former PL members and supporters find positive elements in their experience. Many have gone on to rewarding careers in labor, journalism, social services, the arts. “I became the permanent activist that I remain” thanks to his time in the student movement, writes Eric A. Gordon, now a staff writer for People’s World. But even some “permanent activists” question the value of their work with PL. Joan Kramer, a retired school librarian who died shortly before the book was completed, continued her commitment to political work. But when her “active party affiliation attempts ended,” she wrote in her contribution, “so did my feeling of purpose. It was a kind of death for me from which I have not recovered.”

Many others may feel this way, or may have dropped out of activism completely: the editors contacted over a hundred potential contributors, but less than a quarter came through with essays.

What’s Changed, and What Hasn’t

In his introduction, editor Levin expresses his “hope that another generation can learn from [these experiences] as well as take heart that they are part of a grand tradition of struggle for social justice.” But how much of the PL experience is relevant today?

Sectarianism and groupthink are always dangers for radical movements, but they were exacerbated in the 1960s and 1970s by conditions at the time. U.S. society may be as polarized today was it was back then, but the polarization is different in crucial ways. Fifty years ago the left’s strength was largely limited to campuses and African-American communities. Activism was picking up in other areas—the environment, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights—but the white majority remained hostile. These were people who had benefited from the postwar economic order and were desperately trying to hold onto the benefits even as cracks were starting to show in the order. Any effort to change or even question existing conditions was certain to be met with vehement rejection.

The result was isolation for left groups, and isolation breeds sectarian and cultish tendencies. Following the recessions and other crises of the early and middle 1970s, broader sectors may have been ready to move left, but by then the student movement had largely imploded. What we ended up with was Reagan, neoliberalism, and a culture fetishizing Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

Today’s polarization is more in the left’s favor. After 40 years of “free market” economics, there’s now widespread support for many progressive ideas: government responsibility for healthcare, taxation of the super-rich, the need to address climate change. And for much of the population “socialism” is no longer a dirty word.

But other problems persist.

One is the bad habit of stereotyping the U.S. population. The student left of the 1960s pictured U.S. workers as tall, brawny white males who drove trucks, built skyscrapers, and hated hippies, gays, and feminists. PL members were expected to wear clothes and sport hairstyles from 1950s situation comedies in order to appeal to these images from old Social Realist murals. Somehow the student left had failed to notice that many real-life workers were women, people of color, gays and lesbians; even some of the brawny white males turned out to have more advanced views when activists took the time to talk to them.

The U.S. working class is now significantly more diverse than it was in the 1960s, but the old thinking hasn’t completely died out. Some people continue to think in either/or terms: either we back economic demands that would appeal to male white workers or we support so-called “identity politics”—as if economic exploitation has ever been something that could be separated from racism, sexism, and homophobia. The big difference is that fifty years ago the advocates for this dichotomy tended to be socialists; now it’s mostly establishment Democrats.

Another persistent tendency is social but quickly becomes political. People like to stick to their own groups, and social media use reinforces this. It’s certainly easier to share our opinions with our Facebook “friends,” but going outside and talking to strangers—exchanging ideas, hearing different points of view, and sometimes even learning that other people may know more than we do—is the essence of organizing.

Beckett v. Brecht

This isn’t to say that You Say You Want a Revolution is all dreary political analysis. These accounts are often moving: people are describing and reliving a crucial time in their lives. One writer, Barbara Selfridge, provides an entertaining short story instead of a memoir, an instructive example of how fiction sometimes gives us a better feel for a time and place than a shelf of history papers. The book also features a trove of photographs from the period; their black-and-white depictions of everyday activism are a good corrective to Hollywood’s Technicolor fantasies about the movement.

There are errors and omissions, as in any undertaking as broad as this. One writer inadvertently places the fatal June 1969 Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) conference in December (p.195). Another appears to assign the August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident to the time after that year’s presidential election (p.104 )—a serious oversight, since one factor in the disillusionment of students with the system was the realization that President Johnson was already escalating U.S. involvement in Vietnam even while campaigning as the peace candidate.

In an amusing slip-up (p.226), a writer cites Bertolt Brecht as the author of a popular maxim: “Try. Fail. Try again. Fail better.” This is actually a paraphrase of a line from Samuel Beckett’s Worstward Ho, where the context makes the thought seem more ambiguous than it does in isolation. Still, it’s good advice for current activists—although maybe this time we shouldn’t discount the possibility of success.