Humankind and the environment are hurtling toward unprecedented ecological crises. Global warming, sea level rise, and weather extremes due to carbon emissions are catastrophic enough, but they will mix and combine with ocean acidification, air and chemical pollution, water shortages, deforestation, fishery collapse, soil erosion, and mass extinction, throwing both nature and society off a cliff into the unknown. Not only do we have a mere decade to stave off the worst of these ecological transgressions, the horizon beyond the year 2030 is foggy—this mixture of forces is unpredictable. To resolve these crises requires an extraordinary degree of cooperation, vision, and determination, never before seen in the history of the species. The revolutions of the past will need to look like child’s play.

What is required is the theory to explain the predicament and guide action: the Marxist theory of the metabolic rift. This essay describes the theory as elaborated upon by John Bellamy Foster, describes the arguments of some recent books that use the theory, critiques Project Drawdown and the Green New Deal on these grounds, and further discusses the theory’s importance.

Indeed, the Earth System has changed more in the past 70 years alone than in the past 10,000. Scientists have therefore concluded that modern capitalist society is a geological force akin to the glaciers that inaugurated the Ice Age. Species are disappearing at a rate comparable to that caused by the K-T asteroid impact that ended the Age of Dinosaurs. Insect populations alone have declined by 57% in Germany and by 80–98% in Puerto Rico; a recent global study predicts widespread insect species extinctions by century’s end.

The scale of these changes is severe enough that geologists are on the verge (but not yet officially) of declaring a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene.(1) This new epoch is marked as distinct from the Holocene, which began approximately 11,500 years ago following the retreat of the glaciers and was climatically stable enough to allow the introduction of agriculture. However, by a host of “natural” indicators—greenhouse gas emissions, loss of ozone, tropical deforestation, ocean acidification, fishery collapse, etc.—Earth scientists now say that the geological epoch of the Holocene ended somewhere around 1945. (Perhaps the Trinity nuclear bomb test.) These indicators changed in parallel with other ‘social’ indicators, such as plastic and paper production, water use, dam construction, synthetic fertilizer use, etc. As the Anthropocene Working Group declared, “Not only [does] this represent the first instance of a new epoch having been witnessed firsthand by advanced human societies, it [is] stemming from the consequences of their own doing.”(2) We now live in the Anthropocene, these surges in ecologically destructive indicators known as the “Great Acceleration.”

Metabolic Rifts

The crises we face are immense. To overcome them, we must correctly identify their causes.

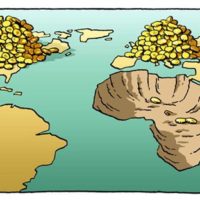

What is the root cause(s) of our ecological crises? Many may want to blame “human nature,” manifested by corporate greed, consumers’ appetites, and the public’s ignorance. This makes little sense: most humans have negligible carbon and water footprints, humans have existed for hundreds of thousands of years, and civilizations have come and gone without provoking global ecological collapse. Rather, that the beginning of the Anthropocene can be located within a decade, the Great Acceleration, suggests the need for a cause more specific than “human nature.”

We must point the finger at modern capitalist society—the Golden Age of Capitalism.

Marxists have long analyzed the destructive relationships between capitalism, humans, and nature.(3) Marx theorized that productive human labor—hunting, gathering, fishing, mining, farming, etc. — involves a material exchange with the environment, a social metabolism with nature. (Metabolism today usually refers to the chemical reactions within an individual body, such as digestion, but here it refers to these reactions on the level of ecosystems.) For most of human history, and for many cultures today still, this social metabolism between humans and nature was and is rather stable. Although a local culture could bring its environment to ruin, the implications were rarely global prior to European colonization and the emergence of capitalism. Over the past couple of hundred years, however, capitalism powered by fossil fuels has transformed a series of local relationships between humans and nature into rifts on a global scale.(4)

As Foster and Clark have explained: In the 1840s, Karl Marx closely observed the research and worries of the premiere German chemist, Justus von Liebig, a major contributor to agricultural chemistry and soil science.(5) Liebig and Marx witnessed British agriculture deplete its soil of essential nutrients, particularly nitrogen. This was explained by Marx, through Liebig, as being a result of peasants, forcibly dispossessed of their lands through enclosure, flowing into the cities. While those who worked the land before capitalism grew food mostly for their own families (subsistence agriculture), capitalist agriculture raises crops as commodities for sale on a world market. The social rifts between town and country, humans and the land, in turn opened rifts in nature: British capitalist agriculture required more fertilizer than the soil could provide, but, human waste, frequently used as fertilizer, was now dumped into rivers and dispersed into the ocean, rather than recycled into the land. To keep up crop production, therefore, the British Empire required an external source of fertilizer. Britain began to raid European catacombs for bones and then colonized Latin American islands rich in guano. Capitalism was now tearing through nutrient cycles around the world to supply its burgeoning agricultural sector. Thus, capitalism had introduced a rift in the social metabolism between humans and nature. Although local at the time, the nitrogen cycle has since been thoroughly disrupted. Worse, not only is excess nitrogen converted into nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, the Haber-Borsch process that produces artificial nitrogen also depends on carbon emissions, thus contributing to other ecological rifts.

Sociologists Stefano B. Longo, Rebecca Clausen, and Brett Clark have applied Marx’s theory of the metabolic rift to the world’s fisheries, many of which are on the verge of collapse.(6)(The Atlantic cod fishery collapsed in 1992.) Like British agriculture, fisheries of Mediterranean bluefin tuna and Pacific Northwest salmon survived for thousands of years without fatal disturbances to the environment’s metabolic cycles and the local culture’s social relations with them. That is, contradicting Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons,” a lack of private ownership did not entail overfishing and destruction; rather the Indigenous peoples of the Northwest and the fishermen of Sicily and Sardinia had their own means of regulating the commons, whether by fishing at only certain times of the year or using sustainable technologies that allowed for reproduction. These peoples treated these resources as necessary for survival and livelihood, rather than for sale on the global market. (What is the point of taking as many fish as possible if they will just rot on the shore, rather than be eaten?) But, as capitalism became entangled with these ecosystems, particularly via the canning industry, the fish became commodities for sale. Thus began the “tragedy” of commodification and the opening of new metabolic rifts.

Once capitalism introduces a metabolic rift, it becomes nearly impossible to resolve; rather, in its perpetual need to grow and accumulate, to solve one rift, it creates another. The tragedy of overfishing has given way to the farce of fish farming, aquaculture, and genetic engineering. Capitalism cannot control itself. Rather than stepping back extraction and production to allow these fish populations to stabilize, it reinvests its profits into further commodifying the fish themselves, tearing them from their environments, and raising them in concrete tanks. The alienable becomes the alien. The commodification of the fish, intentionally separated from their environment, exacerbates the metabolic rift: farmed salmon do not share the famed upstream migratory patterns of wild salmon, entailing that the millions of tons of biomass and nutrients salmon gather and accumulate in the ocean does not reach their predators or fertilize the streams, lakes, and forests of the Pacific Northwest. The salmon in aquaculture are not allowed to migrate at all. Capitalism has torn the salmon away from its habitat and its thousands-years-old role in the metabolic order of the region. Instead, the social metabolic order of capitalism—profit before all else—reigns supreme, redirecting all cycles to benefit its regime.

Because these rifts in nature result from capitalism, they co-evolve with social rifts, each depending on the other. Enclosure forced British peasants into the cities. Evicted from their homelands, the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest are alienated from the natural environments which they inhabited for thousands of years. Sardinians and Sicilian fishermen are crowded out by Mitsubishi, tossed aside by capitalism as useless, to fuel the demand for sushi in Japan and the United States. As with the British Empire’s need for guano, imperialism and settler colonialism are deeply intertwined with these rifts.

This same capitalist logic reduced the vast, rich and fertile North American prairies into ecologically sterile monocultures, possibly only through the genocide of Native Americans, partially conducted through the ecocide of millions of bison.(7) This was only one example of what Hannah Holleman describes as the first global metabolic rift:

dust-bowlification” (instead of “desertification”). Rampant among the colonial empires of Africa, India, and America, [Australia?], the American Dust Bowl being perhaps the most severe, these social and ecological disasters were the result of the same underlying conditions: mass erosion from cash crop agriculture forced upon Indigenous peoples and lands as a part of (settler) colonialism. The heart of the Dust Bowl, Oklahoma, had been open to white settlement for only a few decades before its agricultural ruin. Despite the temporary fixes of the Second New Deal, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, erosion has only worsened, not only in the United States, but around the world: the UN predicts that at current rates we have a mere 60 years of topsoil left. Yet another metabolic rift: the depletion of topsoil due to intensive farming exceeds the rate of its creation.(8)

unequal ecological exchange?

Malm/Fossil Capital: Capitalism has now opened the deadliest metabolic rift of all: a complete disruption of the carbon cycle. This rift entails global warming, ocean acidification, and mass extinction. Although the first Industrial Revolution was powered by wind and water, Andreas Malm has shown that capitalism could not rely much longer on these forces of production.(9) Not because steam-based coal power was more powerful or efficient (to the contrary), but further expansion through water power would have required capitalist collaboration and increased care for their labor force. Coal, an alienable resource that could be shipped and consumed by an individual capitalist within the city, facilitated inter-capitalist competition and their control over wage labor (without needing to provide for them). Only later did coal-based steam power become powerful and efficient compared to waterwheels. Fossil fuels are baked into capitalism; capitalism could not endlessly accumulate without breaking open the carbon cycle. This rift has enormous cascading effects: quantitative changes in the level of carbon in the atmosphere, the highest in 400,000 years, mediated through the greenhouse effect, result in qualitative ecological changes: a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene.

But it was not until World War 2 that rifts in the carbon cycle transformed into global ecological crises. Ian Angus points to several factors that have contributed to what Foster calls a “qualitative change in the level of human destructiveness.”(10) The American intervention into World War 2 ramped up petroleum extraction, automobile production, corporate concentration, and industrial chemistry (plastics, a byproduct of petroleum, as well as synthetic fertilizers), funded by the federal government with guaranteed profits. These same profiteering vultures established ties to oil-rich Saudi Arabia, ensured huge military budgets during “peacetime,” domesticated the labor force following the largest strike wave in history, and descended upon a destroyed Europe to reap the wealth from rebuilding France and West Germany. Concurrently, the U.S. state encouraged suburbanization and further automobile production, industrialized agriculture, promoted globalized production that exploits not only cheap labor, but wrecks the environment, and supported plastic production. Although much of the world decolonized in this period, neo-colonialism ensured the continued extraction of minerals and cheap labor. The key to all of these developments was, and is, cheap oil. Thus, the “Golden Age of Capitalism” (1946–1973) was simultaneously the Great Acceleration, the inaugurator of the Anthropocene, the unprecedented rift between humans and nature.

Reforms: Useful, but Insufficient

Having established the underlying conditions that have birthed our ecological crises, we need to transform those conditions if we are to redirect our ecological course. It is clear that simply(!) reducing carbon emissions is insufficient—capitalism has wreaked more havoc than that. Reducing carbon emissions does not fully address mass extinction, fishery collapse, erosion, unsustainable water use, and nitrogen pollution (although these problems are underwritten by fossil fuels). Therefore, as Julia Thomas writes,

The Anthropocene’s interrelated systematicity presents not a problem, but a multidimensional predicament. A problem might be solved, often with a single technological tool produced by experts in a single field, but a predicament presents a challenging condition requiring resources and ideas of many kinds. We don’t solve predicaments; instead, we navigate through them.

As Thomas argues, the nature of the predicament precludes any simple technical legal or technological fixes. Reforms are unequal to the task. If capitalism lies at the heart of our predicament, then no suite of reforms that allows the capitalist system to remain will allow us to successfully “navigate” through the predicament. Reforms should be pursued when the opportunities presents themselves, but—this is key—we need to create the opportunities for ecological revolution.

Ian Angus, in Facing the Anthropocene, provides a useful case study regarding a past metabolic rift that was seemingly resolved: the hole in the ozone layer. However, DuPont phased out CFCs only because they had suitable replacements in the works; a rather simple technical fix was available as a substitution. In that way, we were lucky. Ironically, though, the replacement chemical is a leading carbon emission. Substitutions of various chemicals or power sources are crucial again today, but alone are insufficient—the predicament is too complex.

So long as profit remains the motive drive of our society, we cannot heal the rifts in both nature and society. We need to also transform the social relations that drove the world to its current crises. An ecological and social revolution must occur in tandem.

Why the Theory of Metabolic Rifts Matters

The importance of theory to social movements is frequently questioned, and rightly so, so this section puts forward the argument on why this theory should be embraced, particularly through Project Drawdown and the Green New Deal. [better wording]

Just as social rifts and natural rifts co-evolved with each other, their resolution must also co-evolve.

Project Drawdown illustrates both the promises and limits of reform. Project Drawdown is a group of scientists and policy writers, in cooperation with wealthy donors, that released what is hailed by some as the most comprehensive study of what is required to reverse global warming. Drawdown refers to “that point in time when the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere begins to decline on a year-to-year basis.” The project contains a wealth of information, particularly with regard to technologies and practices already available.

Project Drawdown has severe limitations, however, in that it does not address political economy. To their credit, they address some social solutions, such as the mass education of the world’s women. But, there is no mention of the need to scale down the size of the U.S. military, let alone any questioning of capitalism and imperialism. Considering that the book’s foreword is penned by a billionaire suggests that Drawdown cannot advocate solutions that endanger the ruling class; instead, they must remain within the claustrophobic confines of capitalism. Ironically, a reviewer hailed the project as “getting at the roots” of climate change, but the precise problem with Project Drawdown is that it does not address the roots at all; rather, they are trimming the leaves. Moreover, although Drawdown calls for a mass movement, it presents no political program to do so. This is because Drawdown cannot—it has deliberately circumscribed itself from proposing the holistic program required to address the ecological crises.

Unfortunately, Drawdown’s confinement within the capitalist system cannot address the political economy that is stacked against them, even within their (relatively) limited proposals. For example, Angus reports that privately-owned and state-owned oil and gas companies have a combined capitalization of $6,729 trillion, more than the world’s banks combined.(11) $15–20 trillion is invested in infrastructure; global proven reserves are worth $50 trillion. Clearly, the oil companies will not walk away from these investments just because we ask them to do so. Foster pointed out in a recent interview that the oil giants are determined to exploit their oil reserves to the fullest.

As Angus points out, what makes our current predicament different from the major American projects of the past—WW2 mobilization, the moon shot, the International Highway System—is that those were massive federal investments in oil production and capitalist/imperialist relations. What we need today is the complete opposite. Thus, while we may gain inspiration from the mobilization for World War II as a model to combat climate change, we must also learn from the failures to mobilize against World War II.

Ultimately, Project Drawdown describes how to close the carbon rift, while paying less attention to other material and social rifts. The ecological crises, however, require us to address all natural rifts and social rifts. For example, Drawdown likely sympathizes with the fight of the water protectors against the Dakota Access Pipeline simply because it involved preventing an increase in carbon emissions. However, nothing they advocate addresses the social rift between the Dakota, the United States, and the land.

Rather alarming is that Drawdown points to Indigenous oversight and management of lands as incredibly effective (#39), particularly in preserving tropical forests (#5), but because of their political program, they cannot address the peril these communities face beyond climate change: the far-right Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, praised by President Trump and the Economist, has vowed to develop these lands for agriculture and to revoke the special status Indigenous peoples are currently granted. Again, the material rift in the carbon cycle is is dependent upon a social rift between the Indigenous peoples and the capitalist state that now encompasses them.

As mentioned above, the rifts in the world’s fisheries are as disastrous as the carbon rift creating climate change. Longo, Clausen, and Clark point out that while the ranching of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean as well as quota systems around the world are designed to ‘save’ specific fish populations, they do not consider ecological or societal needs. The purpose of ranching bluefin tuna is not to help the communities in Sicily who fished their waters for at least 10,000 years without collapsing the fishery; instead, its purpose is to supply tuna to the Japanese and American sushi markets. That Mitsubishi is the largest tuna rancher in the Mediterranean means that even if regulations limited their take, the local communities remain alienated from their own environment.

Therefore, the Marxist theory of metabolic rifts keeps our analysis and vision holistic, rather than reductionist. There is more wrong with modern capitalist society’s relationship to nature than too much carbon in the air; the entire material interaction between nature and human society is distorted, on both local and global scales. It is no coincidence that solutions advocated for within the capitalist system only exacerbate the problems in another rift.

In Project Drawdown’s defense, they do provide some surprising results with clear social implications.(12) For instance, the ninth most effective reduction of carbon would be a wider adoption of silvipasture, in which livestock are allowed to pasture among trees (“silvi-”), rather than clearcut fields, which can be further integrated into a system of regenerative agriculture (#11). Thus, within some ecological limits, livestock are compatible with sustainability, particularly due to their role in nutrient cycling (i.e., the nitrogen rift). Therefore, peoples who live in areas where the land is suitable for grazing, not crop agriculture, can maintain their ways of life, whereas others will have to find ways to vastly reduce their meat consumption (#6). That is, totally eliminating meat could introduce new metabolic rifts, both material (nitrogen) and social (in shepherding cultures). A holistic view of ecological sustainability is essential to navigating the ecological predicament.

Green New Deal

The Green New Deal is the current policy proposal that will drive mainstream environmental conversations in the United States. It is undoubtedly a major step forward. That Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal emphasizes a deadline of 2030 may be its most crucial aspect—it embraces the speed at which a response must be mustered, rather than kicking the can down the road to 2050 or 2100. Its focus on environmental justice (social rifts) is welcomed and its federal job guarantee is critical for success. For example, because its unabashed declaration that air travel needs to be reduced entails major shifts in employment, those workers must be helped through the transition. It could even provide employment where labor is needed to carry out the sustainable ecological tasks on its agenda.

While the language of the Green New Deal does not explicitly challenge capitalism, its demands surely will. Whether or not Ocasio-Cortez recognizes this contradiction is unclear. However, socialists can treat it as a transitional set of demands, in which it puts forward necessary (but incomplete) solutions within a society that will not allow it. If a mass movement arises to push the Green New Deal through, it may not only fracture the Democratic Party, but may encourage more of the working class to interrogate the fundamental flaws of capitalism.

A major weakness of the Green New Deal (in its current form) is its unmentioned acceptance of imperialism, both military and economic. For example, it does not mention the military. The military worsens ecological crises in two ways: first, the U.S. military itself emits enormous amounts of carbon and pollution; second, the U.S. military is a tool for capital to suppress ecological movements around the world, especially when it comes to oil. Thus, budget cuts, base closures, and troop withdrawal are necessary measures.

Economic imperialism is more complex, but a quick example should suffice for illustration: wind turbines are not “free.” They, too, have material origins! The mining of minerals necessary for their construction, such as cobalt, is not only ecologically destructive, but is performed by miners, including children, laboring under horrific working conditions. The recent collapse of a Brazilian dam constructed for iron ore mining that lead to over 150 deaths is a case in point. The Australian firm “BHP Billiton’s Ok Tedi open-pit copper and gold mine in Papua New Guinea…discharges 200,000 tonnes of waste into the local environment every day, polluting water supplies [and] soil, and adversely affecting the lives of 30,000 people.” Child labor (slavery) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in cobalt mining is rampant. Because the Dakota Access Pipeline was built for oil, the necessity of opposition was clear, but when those cases of imperialism are for the sake of wind turbines, environmentalists might turn the other way. Therefore, a Green New Deal must close the social rifts widened by centuries of imperialism and ensure that the ecological sustainability of the United States does not rest upon a “green imperialism.” Already the wealth of the United States and Europe is built upon “unequal ecological exchange” with Africa, we must refuse to worsen it for the sake of being green.

The United States must ensure that the wealth of green technology, for example, is not founded upon the economic and ecological explanation of Africa.

Vantage Point from the Future

Marxists typically refrain from speculating on the details of a future communist society. Because of the complexity of the situation as well as a commitment to an expansion to democracy, to do so is to be “unscientific” and “utopian.” However, one thing we know for sure is that any social revolution worth waging must be ecological. Moreover, among the first tasks of any social revolution will be to address the metabolic rifts the capitalist society has opened. As Marx wrote,

What we have to deal with here [in analyzing the programme of the workers’ party] is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it comes.

Metabolic rifts, along with racism, sexism, imperialism, alienation, pollution, mass extinction, and other social ills, will be the birthmarks of the new society. Therefore, metabolic rifts explain the current predicament of capitalist society’s destructive relationship with nature as it has historically developed, the theory also dictates, partially, the necessary actions required by a revolutionary society. The exact details—some of which are known, some of which are not—must be worked out democratically.

A capitalist society organizes production for the maximization of profits. A socialist society organizes production for the fulfillment of human (and nature’s) needs. For example, housing is built for the purposes of profit on behalf of banks, developers, and real estate agencies, with the byproduct of providing shelter. Hence, there are more houseless people in the United States than there are empty houses. If housing was built according to social needs, we could easily eliminate houselessness. A planned economy could apply this form of production to every sector: transportation, manufacture, agriculture, etc. However, the metabolic rift demonstrates the need to consider not only human needs, but the needs of nature, so as to bring society and nature into harmony.

One social rift that bears specific attention is that between pro-fossil fuel production building trades workers and those opposed to them: Indigenous peoples, environmentalists, and political progressives. Best illustrated by Standing Rock, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and North America’s Building Trades Unions supported the pipeline for the sake of jobs, whereas the opposition included bus drivers, postal workers, and nurses. A Green New Deal with a federal job guarantee can hopefully win the support of these building trades unions, but it is not at all straightforward: the U.S. economy is increasingly tied to logistics, a sector mostly powered by fossil fuels. How to win truckers over to an eco-socialist cause, for example, will require an immense amount of organizing and tact. But, as I have argued elsewhere, this sector is one of the keys to the socialist cause. Thus, a contradiction at the heart of our predicament.

Conclusion

On a superficial level, the ecological crises confronting society are disconnected: a society can overfish whether or not the world’s nitrogen cycle is disrupted. Another can transform its arable land into wasteland whether or not the temperature increases. However, in this world of ours, they are connected, but perhaps not on the surface. The Marxist theory of metabolic rifts shows that the same engine powers all these ecological problems. That engine is capitalism. This same engine results in the social rifts of wealth inequality, sexism, racism, and the general problems of alienation.

Capital’s need to grow infinitely conflicts with the Earth’s finite wealth. It can temporarily stave off a crisis, perhaps by switching to renewable energy, but technologies that generate renewable energy are not themselves renewable. At some point, the minerals required for wind turbines and solar panels will run out, or the waste material may become unmanageable. Or, perhaps, we, as a society, conclude that the labor involved can be reduced so as to extend leisure time rather than satisfying increased energy production.(13) The point is that we need to rethink and reorient our relationship to nature in every possible way.

What we do know, though, is that if these metabolic rifts are not fixed soon, one of them will open a chasm too wide to again resolve. Between increased air temperature, sea level rise, mass extinction, soil erosion, among others, society will fail to thrive. The “predicament” that confronts us has a single cause—capitalism—but is mediated by a complex entanglement of factors that will not be resolved by the ‘simple’ overthrow of capitalism.(14) We must then not fall prey to reductionism, must not focus solely on reducing carbon emissions, but consider all that confronts us, ecologically and socially, and aim towards their mutual resolutions. Capitalism has alienated and continues to alienate humans from nature, and if not stopped, will leave behind polluted and empty wastelands.

Notes

- There is some disagreement among the left about the name itself, but that does not concern us here. Some worry that the name “anthropocene” blames all humans (“anthropos”) as responsible and suggest instead Capitalocene.

- Quoted by Ian Angus, p. 57.

- Marx’s theory of the metabolic rift was long neglected, largely due to Marx’s own scant references to such and the Soviet Union’s apparent disregard for environmental problems in its later years, but scholars such as sociologists John Bellamy Foster and Paul Burkett have shown that Marxism can readily account for the ecological crises of the modern day. See John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, “Marxism and the Dialectics of Ecology,” Monthly Review 68:5 (2016).

- “Very rarely” is mostly a reference to Genghis Khan. See also the recent study that concluded European colonization and genocide of the Americas contributed to the “Little Ice Age.”

- John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, “The Robbery of Nature,” Monthly Review 70:3 (2018).

- Stefano B. Longo, Rebecca Clausen, and Brett Clark, The Tragedy of the Commodity: Oceans, Fisheries, and Aquaculture (Rutgers University Press, 2015).

- Hannah Holleman, Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of “Green Capitalism” (Yale University Press, 2018); Hannah Holleman, “No Dust Bowls, No Empires: Ecological Disasters and the Lessons of History,” Monthly Review 70:3 (2018).

- Added to this rift in the soil is the rift in the water cycle, as seen in the emptying of the Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains.

- Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming (Verso Books, 2016).

- Quoted by Ian Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, p. 217.

- Ian Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, p. 170.

- What is somewhat promising is that the two most effective “solutions” to global warming are technical fixes: 1) replacing the HFCs that replaced CFCs with available chemical substitutes in air conditioners and refrigerators, 2) mass construction of wind turbines.

- This gets into issues about how a global socialist society would function which is far beyond the scope of this essay.

- This is illustrated to some degree by the experience of the Soviet Union, which like capitalist societies, had a mixed record when it came to ecological concerns. See “What About the USSR?” in Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, pp. 208–211. Really, the question is too complex for the scope of this essay and requires more investigation from the author.