Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In December 2019, several people began to develop infections in Wuhan (People’s Republic of China); early signs indicated that the virus had emerged out of the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, but there is no certainty about that verdict. This 2019-nCoV–or novel coronavirus–infected hundreds of people in the first month. The authorities declared that thirty cities would be under Level 1 Emergency, and large parts of the country–including Wuhan (population 11 million)–would be entirely quarantined. By 30 January, when the confirmed cases of the infected rose to almost 10,000 people, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared a global health emergency.

At the WHO press conference, its Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said, ‘The speed with which China detected the outbreak, isolated the virus, sequenced the genome and shared it with WHO and the world is very impressive, and beyond words. So is China’s commitment to transparency and to supporting other countries. In many ways, China is actually setting a new standard for outbreak response. It’s not an exaggeration’. The newly announced Qiao Collective published a short report on the advantages of the Chinese socialist system when it comes to an epidemic of this kind as opposed to a capitalist system, which cannot understand what it means to put people before profit. Ghebreyesus ended his statement with three powerful sentences:

This is the time for facts, not fear.

This is the time for science, not rumours.

This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.

The question of facts and solidarity is significant. Grotesquely, the U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross hoped that the Coronavirus outbreak would hurt the Chinese economy and bring jobs to the United States. Apart from being insensitive, the comment reveals a lack of understanding about the supply chain resiliency problem of places such as the United States, which rely upon Chinese manufacturing for far more than cars and computers; 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients for drugs used in the United States are produced in China and India, and 90% of U.S. vitamin C doses are made in China. Ghebreyesus’s plea for solidarity, not stigma should guide our attitude–not the trade war that seems to be an obsession of the imperialist bloc.

In the midst of his statement, WHO Director-General Ghebreyesus said, ‘I also offer my profound respect and thanks to the thousands of brave health professionals and all frontline responders, who in the midst of the Spring Festival, are working 24/7 to treat the sick, save lives and bring this outbreak under control’. Resources went towards the building of new hospitals, such as the Wuhan Huoshenshan Hospital, built at record speed and opened this week.

Doctors and nurses from within China volunteered to go to Wuhan to help those infected and to contain the outbreak. Zhang Wenhong, the chief doctor of the Shanghai Medical Treatment Expert Team, said that Communist Party of China members who are doctors and medical should be the ones at the frontline.

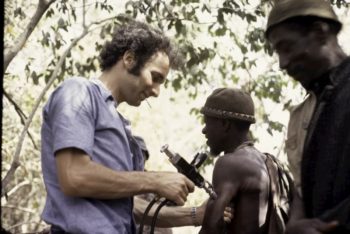

Vaccinations. Roel Coutinho uses a jet injector, Ziguinchor, Senegal 1973.

When a doctor and a nurse join the Communist Party, Zhang Wenhong said, they take an oath to serve the people; this is what now guides them. In Wuhan Union Medical College, thirty-one nurses cut their long hair to shorten the time it would take to prepare for their shifts; young doctors in the Communist Party flocked to take shifts at the hospitals to stem the virus. State-owned firms are producing masks in record numbers, food controls have prevented opportunistic inflation, and the hit to the country’s GDP has been set aside as a consideration for the planners. People, they say, must be put before profit.

At Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, we have been thinking about the global health crisis alongside the immense commitment of socialists–including socialist states–to medical solidarity. The question was raised when both Bolivia and Brazil deported the Cuban doctors, most of whom had become the bedrock of medical care amongst the industrial and agricultural working class of these countries. In 2014, Time chose the Ebola fighters as its person of the year. When the Ebola outbreak struck Western Africa, the Cuban medical community decided to go and help fight the disease. Of the nurses and physicians who went to West Africa, the largest continent–256 people–came from Cuba. The commitment was so great that Dr. Felix Baez, one of the Cuban doctors, contracted Ebola, recovered in a Swiss hospital, returned home to Cuba, and then wanted to leave once more for Sierra Leone to help his comrades there. A month later, he was back to work in Port Loko, two hours outside Freetown.

Dr. Hu Ming, the Intensive Care Unit Director at Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital, was infected by the coronavirus in its early days. After he recovered, like Dr. Felix Baez, Dr. Hu Ming went back to his ward. He has patients who need socialist doctors like him.

Dr. Hu Ming, the Intensive Care Unit Director at Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital, was infected by the coronavirus in its early days. After he recovered, like Dr. Felix Baez, Dr. Hu Ming went back to his ward. He has patients who need socialist doctors like him.

Yet, in September 2019, the United States accused Cuba of human trafficking doctors, and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro called the 8,300 Cuban medical personnel in Brazil ‘slave labour’. It tells you a lot about the divergence of world views between Bolsonaro and the Cuban doctors that he would see their socialist commitment as slavery.

It is why our Dossier no. 25, People’s Polyclinics: The Initiative of the Telugu Communist Movement (February 2020), is on a magnificent experiment in people’s medicine–the polyclinics in India run by doctors affiliated with the Communist Party who work to serve the people rather than to enrich themselves financially. The pressing need for medical personnel was evident when the British Empire collapsed. At the end of British rule in India, the medical system was barely existent. There was one doctor for every 7,200 Indians. India won its freedom, but with a literacy rate at 11% and poverty at startling levels, freedom was more an aspiration than a reality.

Students of the Dr. P. V. Ramachandra Reddy People’s Polyclinic (PPC) Nursing College undergoing karate training. Photo credit: Nellore People’s Polyclinic.

In the Telugu-speaking parts of India (now 86 million people), doctors affiliated with the Communist movement set up clinics and hospitals–notably the Nellore People’s Polyclinic–to provide medical care to the working class and the peasantry. The Polyclinic not only provided care, but it also trained medical workers to take public health concerns into the rural hinterland and small towns. When one of the founders of the Polyclinic said that he wanted to become a full-time revolutionary, the Communist leader P. Sundarayya said to him that being a people’s doctor is itself a revolutionary activity. The dossier offers a window into the left-wing medical personnel who work outside the limelight, and into the medical experiments to undercut the tendency towards the privatisation of health care. Dr. Zhang Wenhong, Dr. Felix Baez, and Dr. P. V. Ramachandra Reddy share an inspirational commitment.

There is no gap as well between them and Dr. Naziha al-Dulaimi, a leader of the Iraqi Communist Party and the Iraqi Women’s League. Dr. al-Dulaimi studied at the Medical College in Baghdad in the 1940s. She was swept up in the anti-imperialist movement, including the al-Wathbah (‘the Leap’) in January 1948 against the renewal of the Anglo-Iraq Treaty. She graduated from college, and after a stint at the Royal Hospital, went to work at Karkh Hospital. Dr. al-Dulaimi set up a free medical clinic in the Shawakah district of Baghdad. As punishment for her communist activities, the authorities transferred her around the country–to Sulaimaniyah, to Karbala, and to Umrah. In each place, she set up a free clinic to serve the poor. Dr. al-Dulaimi worked in southern Iraq to eradicate the Bejel bacteria, or yaws, which strikes children with great force. After the Revolution of 1958, Dr. al-Dulaimi was made the minister of municipalities; she was instrumental in the creation of the Thawra (‘Revolution’) district of Baghdad, and of the passage of the feminist 1959 Civil Affairs Law. When the Ba’ath came to power, she went into exile, but–till her last days–remained both a people’s doctor and a communist.

If Dr. al-Dulaimi were alive today, she would have joined the doctors and nurses who have gone into Wuhan and other parts of Hubei province to help defeat the coronavirus.

If Dr. al-Dulaimi were alive today, she would have joined the doctors and nurses who have gone into Wuhan and other parts of Hubei province to help defeat the coronavirus.

In August 1960, Che Guevara delivered a lecture in Havana on revolutionary medicine. He mentioned that a few months before his lecture, a group of doctors refused to go to the countryside to work unless they were paid more. This is normal, said Che, a function of the capitalist logic that impedes our sense of humanity. What if revolutionary Cuba did not charge students to become doctors, but if the social wealth enabled young people to be doctors, ‘if two or three hundred peasants had emerged, let us say by magic, from the university halls?’. Cuba in 1958 had about one doctor for every 1,051 people. The University of Havana Medical School had been shut down by the dictatorship in 1953; it was re-opened in 1959 with only 23 of its 161 professors (they, with other doctors, fled to the United States). The Revolution turned to the peasantry, who studied medicine, and then–with immense commitment–went on missions to bring Cuba’s medical skill to other parts of the world. Today, there is 1 doctor in Cuba for every 121 people; in the United States, there is 1 doctor for every 384 people. These Cuban medical workers, like the medical workers at the polyclinics in India, and the medical workers in China are–as Che said–a ‘new weapon of solidarity’.

This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.

Warmly, Vijay.