This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

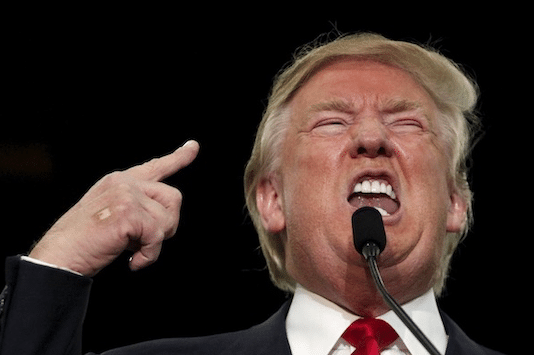

Six months ago, on January 30, the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, announced a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). Ten days before this, the Chinese government had said—to great alarm—that the coronavirus could be transmitted from human to human. The contagiousness of this virus led the WHO to make the declaration, which came a month after the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention told their counterparts in the United States about the virus. On the day that the WHO declared the PHEIC, Trump gave a press conference, where he bewilderingly said, “We think we have it very well under control.” From January 30 onward, the Trump administration’s response to the virus was incoherent and outrageously incompetent.

On July 31, the WHO’s International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee met and the following day asked governments to continue with and even increase their work of educating their populations to be vigilant with the basic WHO rules (to wear masks, to keep hands clean); the WHO also asked governments to “continue to enhance capacity for public health surveillance, testing, and contact tracing.” These recommendations when they were first issued on January 29, and since they were updated on June 5, had been immediately followed by the governments of Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, Venezuela, New Zealand, South Korea, and the Indian state of Kerala. But they were forcefully ignored by countries such as Brazil, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Surprised

On July 30, the executive director of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Program, Dr. Mike Ryan, told a press conference that he was “certainly surprised” by the “slowness in general of systems to react on things like contact tracing, cluster investigation, testing, [and] being able to bring a comprehensive public health strategy to bear.” The WHO, he said, spent the first months after January offering technical and operational assistance to countries “that we would traditionally feel need that assistance.” This was a mistake. In many countries that they assumed would handle the pandemic effectively, such as the United States of America and the United Kingdom, the entire system failed.

“I think we’re all learning lessons; that there’s been a deep underinvestment in the public health architecture,” Dr. Ryan said. This is a UN official being polite; it seems that he would like to simply say that in countries like the United States, the government utterly failed the public.

There are more than 18 million active cases in the world, with more than 4.8 million of them in the United States of America. The U.S. has about 59,000 to 66,000 cases per day—a catastrophically high number, especially when you compare it to Laos and Vietnam, which have almost no new cases and which have few fatalities (Laos has none; Vietnam has had six). How does one understand the total failure of the Trump administration to break the chain of the infection?

Austerity

From 2010 to 2019, the budget for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was cut by 10 percent. In February, after the PHEIC had been declared, the Trump administration proposed a funding cut to the Department of Health and Human Services of $9.5 billion, which included a 15 percent cut to the CDC ($1.2 billion) and a sharp decrease in the contribution to the Infectious Diseases Rapid Response Reserve Fund. In March, Trump’s budget team defended these cuts.

Not only has the U.S. government cut the public health budgets for the CDC and other federal agencies, but it has also made sure to slice the funds for state and local public health officials. In 2009, a report by Trust for America’s Health found that there “has been a shortfall of $20 billion annually—across state, local, and federal government—in funding for critical U.S. public health programs.” A more recent study by the Trust for America’s Health found that public health funding for local governments fell from “about $1 billion after 9/11 to under $650 million” in 2019. A superb Associated Press investigation found that “nearly two-thirds of Americans live in counties that spend more than twice as much on policing as nonhospital health care, which includes public health.”

Between 2008 and 2017, as a consequence of the austerity, state and local health departments had to lay off 55,000 people—one in five health workers. In 2008, the Association of Schools of Public Health reported that by 2020 “the nation will be facing a shortfall of more than 250,000 public health workers.” Nothing was done to heed this warning.

Tests

In March, Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner was tasked with forming a committee to manage the pandemic. On the committee were cronies of Kushner, including his former college roommate, supposedly the “A-team of people who get shit done”; absent from the committee were leaders of key departments in the U.S. government, including Admiral Brett Giroir who had been appointed on March 12 to coordinate COVID-19 diagnostic testing (he left the position in June).

Despite the cronyism of the committee, it is said to have produced a plan that included setting up “a system of national oversight and coordination to surge supplies, allocate test kits, lift regulatory and contractual roadblocks, and establish a widespread virus surveillance system.” The national testing plan, it was said, would be announced by President Trump in early April. It was not.

Instead, Trump continued to brag about his administration’s response, which was essentially nil. On April 27, Trump was joined at the White House by the CEOs of Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, who both bragged that their firms would be able to handle the testing. Steve Rusckowski of Quest Diagnostics said in Trump-style, “we’ve made tremendous progress.” They were then doing 50,000 tests a day; they are currently doing about 150,000 tests a day.

The issue is not the number of test samples taken per day, but the time it takes to get the results to the person tested. In mid-July, Dr. Rajiv Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, said that he is disheartened by the private sector testing system. “No one expected that the lag time would go from a day or two to seven or, in some cases, 14 days,” said Shah. “With the seven-day lead time you basically aren’t testing at all, it’s the structural equivalent of doing zero tests.” These are powerful words from the former head of USAID, whose foundation released on July 16 a “National COVID-19 Testing Action Plan,” which should have been developed by the U.S. government in March and put into action immediately. The Trump administration neither adopted the White House committee’s plan from March, nor have they adopted the Rockefeller’s plan; they have, in fact, announced no plan.

Three days after the Rockefeller Foundation released its plan, Trump made another one of his ludicrous statements. He went on Fox News and said, “Cases are up because we have the best testing in the world and we have the most testing.” There is nothing factual about either of these claims. In June, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield said that as many as 90 percent of the cases in the U.S. are being missed because of an absence of testing. There are probably, therefore, 20 million people with the disease rather than the 2.3 million confirmed cases. More testing would show higher numbers.

Testing and contact tracing would allow precise isolation for populations who could carry the infection to others. None of this is happening. When Admiral Giroir was asked in a congressional hearing on July 31 if it was possible to get tests returned within 48 to 72 hours, he replied, “It is not a possible benchmark we can achieve today given the demand and supply.”

The incompetence of the Trump administration—mirroring the dangerous incompetence of Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and Narendra Modi of India—coming on top of a destroyed public health system and a failed private sector testing establishment has condemned millions of people in the U.S. to catch the disease and pass it on. There is—thus far—no prospect of breaking the chain of infection in the United States.