This article is the second in a three-part series on the ways online historians and writers are shaping the worldviews and mindsets of young Chinese. Read the first article here.

As I discussed in my first article, young Chinese are in the midst of a major reappraisal of their country’s modern history, one that is reshaping their attitudes toward the so-called socialist period, roughly defined as the years between the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the start of “reform and opening-up” in 1979.

Contributing to this shift has been a wave of pop history articles and videos on social media seeking to revise popular understandings of socialism, Mao Zedong, and the early history of the People’s Republic. But articles on their own don’t make a movement; they’ve resonated so deeply because of how very different young Chinese experiences and attitudes are from previous generations. Put simply: Life under capitalism isn’t all it was cracked up to be.

Young Chinese born in the 1990s and 2000s grew up in an era of rapid economic growth and a corresponding rise in China’s overall national strength. Especially after 2008, when the West found itself mired in a global economic crisis of its own making and China grew to become the second-largest economy in the world, Western ideologies such as liberalism have gradually lost their post-Cold War cultural hegemony.

This has opened a window for people to comprehensively reconsider their understanding of Chinese and world history. Many young Chinese reject the neoliberal consensus that there is no alternative to Western development strategies, instead favoring a more cool-headed, analytical approach to comparing the advantages and disadvantages of various political ideologies. Online, historians and hobbyists emphasize the effects of industry, social class, the military, and geopolitics on national development–while warning their audience to beware the sinister intentions of foreign powers and to avoid simplistic “hipster” attitudes toward politics.

Part of what’s going on here is generational. For years, those interested in learning more about China’s history were not presented with a truly diverse set of opinions, but rather a raft of works created amid the singular ideological trends of the ’80s and ’90s. Many of these were rich in information, but also heavily infused with liberal political and cultural bents that do not resonate with young people. Even setting ideology and experience aside, it’s only natural for a new generation to chafe at the axioms of those who previously dominated the country’s cultural discourse.

For example, a decade ago, the Chinese mainland was still in the clutches of a wave of nostalgia for the Republican period, one which heavily romanticized the pre-Communist Kuomintang (KMT) government. Today, however, it’s become popular even on former liberal strongholds like question-and-answer platform Zhihu to write long posts featuring archival photos and documents that specifically highlight the corruption and social decay of KMT rule, thereby making the case that only the Chinese Communist Party could have engineered China’s rise.

For my money, however, the most important motivating factor behind the embrace of the country’s socialist period is that young Chinese have lived and suffered under capitalism. Their recognition of and appreciation for the CCP’s early socialism-building achievements is underpinned by a broader reappraisal of the history and theory of the international socialist movement since the 19th century.

This reappraisal goes deeper than reproducing zombie narratives or 20th century rhetoric: It’s based on a vivid sense of contemporary life and reality. Young Chinese have spent much of their lives watching the decay of the global capitalist order, the rise of inequality, and the collapse of working class status. The earlier generation embraced pure market ideology, private enterprise, and capitalism, but to many young Chinese who work in the private sector their elders built, these ideas are associated not with unleashing productivity, but the droning pressure of “involution,” feelings of relative deprivation, and grueling work schedules like the 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six-day-a-week marathon known as “996.”

Indeed, almost anywhere you look online, there’s a palpable sense of anger and frustration at capitalism and market ideology. First, young Chinese are forced to work extreme hours with seemingly little to show for it, then they have to listen people like Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma lecture them about how working 996 is a “blessing” or watch as the wealthy profit from their investment and real estate portfolios without having to lift a finger. Recent years have even seen the resurgence of derogatory uses of “capitalist” and other highly loaded terms in popular discourse, as young leftists seek ways to vent their frustration.

A man walks past an oil painting of Karl Marx during an exhibition in Beijing, May 6, 2018. Du Jia/People Visual

Given the circumstances, it’s no surprise that at least some would turn to the most comprehensive, powerful critique of capitalism and markets yet developed: Marxism. To a degree, this leftward shift feels like a return to form. Young leftists are reclaiming the ideological heritage of their country, which was after all founded on the notion of ending the capitalist class’s oppression and exploitation of workers and peasants. And because they grew up in an educational system with mandatory courses on Marxism and socialism, even seemingly impractical or outdated concepts like class and “surplus value” become handy analytical frameworks when many students encounter difficulties later in life.

But the current trend goes beyond the classroom. Indeed, many students complain that their mandated Marxism classes–long treated as pro forma exercises by teachers and students alike–aren’t doing enough to prepare them or give them the knowledge they really want.

They have a point. “If you want to be the masses’ teacher, first you must be their student,” Mao once exhorted. But many teachers of Marxism on Chinese campuses have grown too comfortable with their marginalization to adapt to the changing circumstances and increased demand for their subject matter; others actively belittle Marx, lionizing libertarians like Friedrich Hayek or even KMT princelings like Chiang Ching-kuo in his place.

This forces their students, who generally have little patience for either libertarianism or KMT nostalgia, to look elsewhere. This ironically has driven many to move past the country’s textbooks and start reading figures like Marx and Lenin in their own words. For others, online videos purporting to explain the core tenets of Marxism-Leninism have proliferated, many of them attracting millions of views.

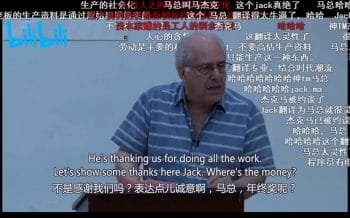

A screenshot from a clip of a Richard Wolff lecture on Bilbili. The scrolling comments are filled with denunciations of Jack Ma. From @陶然堂主 on Bilibili

Interestingly, one of the most popular interpreters of the Marxist tradition isn’t Chinese at all, but the American academic Richard D. Wolff. Netizens have pulled videos of his lectures from YouTube and re-uploaded subtitled versions to sites like Bilibili under titles like “Why Aren’t You a Marxist?” Despite his academic background, Wolff has garnered praise for his clear-eyed analysis and accessible explanations of core concepts, and some of his videos on Bilibili have gone on to rack up more views than the originals. Closer to home, Bilibili has also helped popularize the work of Chinese agronomist Wen Tiejun, whose history, “Eight Crises: China’s Real Experiences, 1949-2009” has enjoyed a concurrent resurgence in popularity and sales.

These developments have raised alarms in some quarters about a leftward drift. But in my experience, for all their frustration and sometimes irrational exuberance, the country’s young leftists are motivated by genuine sentiment and a desire to see their country improve. They want to recapture the ideals of those who fought and sacrificed themselves for socialism and the Chinese revolution–and to build a just, equal society such martyrs would be proud of.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.