In the sticky conversations around rationing life-saving treatments and vaccines during the Covid pandemic, corporate media have elevated some experts without disclosing their troubling views on disability, aging and the value of human life. Meanwhile, media outlets have largely sidelined the voices of disabled activists and others who could speak on behalf of those most affected by the pandemic.

‘Quality of life’

“The stark message to chronically sick, disabled people and elders is that we are ‘acceptable losses,’” Elliot Kukla wrote in the New York Times (3/19/20).

In the first weeks of the Covid outbreak, national media outlets did shine a spotlight on issues for disabled people, including the potential for discriminatory triage guidelines. Disabled voices appeared in the op-ed pages of the New York Times (3/19/20, 3/23/20), Washington Post (4/6/20, 4/9/20) and Vox (4/4/20), advocating for their rights.

Disability became a viral social media topic in July 2020, after a Texas woman shared a recording of a doctor refusing life-saving treatment for her Covid-infected husband, Michael Hickson, a Black father of five who was already a quadriplegic with brain damage. On tape, his doctor defended his choice based on Hickson’s lack of “quality of life,” by which he clarified to mean Hickson being “paralyzed with a brain injury,” not the infection. He also referred to Covid medication as being appropriate for patients who are “walking and talking.”

A few national outlets picked up the story, reflecting varying degrees of understanding of the disability issues at stake. Newsweek (7/2/20) leaned on statements by the hospital and care agency only, which defended the doctor’s medical choice but glided over his statements. Nor did Newsweek‘s article itself include all of the doctor’s incriminating words—or any input from disability advocates.

The Washington Post (7/5/20) described the contrast between Hickson’s wife, who wanted life-saving measures used, and his sister, who sought legal guardianship to let him die, as between a “voice of hope” and “a pragmatist,” respectively. The sister’s pragmatism was illustrated by her acceptance that Hickson was no longer “a genius,” or “the person he was before 2017,” when he was injured—with the Post not questioning the assumption that that prior brain damage was relevant to whether he should be saved.

None of the national stories pointed out how the doctor’s statements by themselves violated federal anti-discrimination rules for Covid triage, as a physician pointed out in an op-ed in The Hill (7/15/20). Still, the Hickson case brought brief attention to disability issues, with follow-up stories from outlets like USA Today (7/14/20) and Politico (8/10/20) covering state and local battles for disability rights.

‘Happiness’

Peter Singer (New York Times Magazine, 4/10/20) rejects comparisons of the Covid death toll to Vietnam War casualties, because “this is killing mostly older people. I think that’s really relevant.”

While national corporate media have sometimes, especially early on, centered disabled and affected voices during this pandemic, representatives of affected groups have not been included in conversations about rationing and other policy issues. No advocates of disability or aging were invited to participate in either of two debates on COVID-19 ethical issues published in the New York Times Magazine and hosted by staff writer Emily Bazelon: “Restarting America Means People Will Die. So When Do We Do It?” (4/10/20), and “People Are Dying. Whom Do We Save First With the Vaccine?” (12/24/20).

Both conversations brought together five “thinkers,” as Bazelon described them. Each included author Peter Singer, described as “bioethics professor at Princeton [University].” Singer’s beliefs are guided by a “utilitarian” philosophy, which, he says, “does the most to increase the net surplus of happiness over misery” (NPR, 6/1/20). Singer has received significant positive attention in the last few years from national media outlets . An otherwise glowing article on Singer in Vox (12/11/20) did point to one notable mark on his record:

He has also been at times a controversial figure in modern ethics, alienating many in the disability community with what they’ve called his simplistic and horrifying takes on intellectual disabilities.

Indeed, Singer has argued, repeatedly and emphatically, that parents should be able to euthanize their disabled babies–not just abort fetuses, but kill actual infants. He describes nondisabled lives as “hav[ing] a greater chance at happiness” than disabled lives (New York Times, 2/16/03). Singer also believes that people with significant cognitive disabilities, such as Alzheimer’s disease, cease being “persons,” because they lack self-awareness, and so can ethically be euthanized by caregivers (New Yorker, 9/6/99).

Otherwise, Singer claims to value human and animal life highly (Vox, 10/27/20). He wrote a book called Animal Liberation and opposes eating, testing on or harming animals. (He has not offered an opinion on disabled animals.)

Disabled activists, religious scholars and others have spoken out ardently against Singer’s views for years, describing them as “eugenics” (e.g., Independent,, 10/10/11; National Review, 9/2/13;), which is defined as a coordinated effort to improve the genetic make-up of a population. The most famous eugenicists, the Nazis, sterilized and killed disabled people.

The beliefs that undergird Singer’s positions on disability correspond to some of his opinions on Covid. In the April debate in the New York Times Magazine, and in other writings around that time, Singer argues that the consequences of “lockdowns” are “horrific,” because “more younger people are going to die,” and that most of the people who died have been very old, with “underlying medical conditions.”

In the December New York Times Magazine debate, Singer argues that we should reconsider the plan to vaccinate older people in nursing homes first. “I think we should ask questions about the quality of their lives,” he says. “The objective that we should aim for is to reduce years of life lost.” He has said that he would give up lifesaving measures to someone “much younger” than himself, if that person didn’t have “underlying health conditions that mean that their life expectancy is no greater than mine” (NPR, 6/1/20).

Criticism of Singer was more prominent in mainstream media ten or more years ago, when British media outlets referred to him as “the man who would kill disabled babies” (Independent, 5/13/98) and “the most dangerous man in the world” (Guardian, 11/5/99). Yet Singer’s reputation would not have been a mystery to Bazelon or the Times when they selected him for the two COVID-19 debates. He has published similar views in the Times recently.

In 2017, Singer argued in a Times op-ed (4/3/17) that rape charges were unfair against a woman who had sex with a noncommunicative man with cerebral palsy. Singer’s argument shifted: the man “may lack the concept of consent altogether,” he offered at one point; elsewhere he suggested, even if the woman “wronged or harmed him, it must have been in a way that he is incapable of understanding and that affected his experience only pleasurably.” The Times earlier (1/26/07) gave Singer space to question a disabled body’s autonomy, dismissing qualms about doctors deliberately stunting the growth of a disabled child as “lofty talk about human dignity.”

Singer’s collection of beliefs is peculiar to him and nonscientific, yet he was invited to the Covid debate table among experts on public health. His ideas of “happiness” and “quality of life” are not measurable, and there is no evidence that happiness correlates with physical or cognitive ability. Scientists also cannot predict the life expectancy of anyone with “underlying medical conditions.”

What is more, Singer has no experience working in medicine or public health; bioethics is a humanities discipline, created in the late 1960s. He acknowledges as much in a Washington Post op-ed (4/27/20) on COVID-19, in which he and his co-author suggest people could voluntarily get sick to provoke immunity. “We are ethicists, not medical or biological scientists,” they write.

When it comes to factual beliefs about the pandemic, we defer to expert scientific opinion, as everyone should.

‘Diminishing capacities’

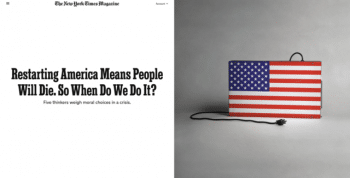

Singer was not the only controversial bioethicist to participate in Bazelon’s New York Times Magazine debates on Covid rationing. Her first conversation also included Ezekiel Emanuel. Unlike Singer, Emanuel does have a medical background, although not in epidemiology; he is an oncologist.

Even more than Singer, Emanuel has become one of the national media’s go-to experts on Covid, making frequent appearances on CNN (10/13/20), MSNBC (10/2/20), CNBC (10/13/20) and other news networks throughout the crisis, as well as writing numerous op-eds and being sought for comment. His media profile was further elevated after President-elect Joe Biden appointed him to his COVID-19 task force. Previously, Emanuel worked on the creation of the Affordable Care Act under President Barack Obama.

A member of Joe Biden’s Covid advisory panel argued that “society and families—and you—will be better off if nature takes its course swiftly and promptly,” and kills him at age 75 (Atlantic, 10/14).

Like Singer, Emanuel has shared disturbing views on disability and aging in the past. Most famously, he published a piece in the Atlantic (10/14) titled “Why I Hope to Die at 75.” In the essay, Emanuel writes that aging “renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived.” The article enumerates a long list of physical and cognitive losses, or “diminishing capacities,” associated with aging. Emanuel lists various conditions that are normally experienced by disabled people of all ages and determines they would make life no longer worth living.

A good deal of Emanuel’s article focuses on how people over 75 almost never achieve great things, which, for him, is associated with production and validation in a capitalist society. When asked about seniors over 75 who do lead active lives, he replied (Technology Review, 8/21/19):

When I look at what these people ‘do,’ almost all of it is what I classify as play. It’s not meaningful work. They’re riding motorcycles; they’re hiking.

Emanuel’s 2014 Atlantic essay ends with a promise to avoid any medical tests or interventions after 75, including the flu shot. He refers to pneumonia as “the friend of the aged” by gifting the elderly with death.

For this and other reasons, advocates for the disabled and elderly were especially concerned when Emanuel’s name was announced as part of Biden’s COVID-19 advisory team. These advocates and others spoke out on social media and in the independent press. Corporate media mostly ignored the controversy in its coverage of his appointment, with Fox News (11/9/20) and USA Today (11/25/20) as notable exceptions. But USA Today only mentioned the controversy to defend Emanuel, calling his Atlantic essay a “personal preference,” even though the essay used “we” and “us” language, making assumptions about shared views on aging and disability. The essay also included a long critique of the American impulse to fight aging.

Emanuel appears on talk shows regularly discussing Covid, but he has rarely if ever been asked about his views on disability and aging since 2014. Bazelon did bring it up during the Times Magazine debate. He told her the premise of his Atlantic article was a “personal preference, not a policy proposal,” the same language used by USA Today.

If Emanuel’s outlook on aging and disability is a “personal preference,” he has nonetheless pursued policies that seem to align with it. During Obama’s presidency, he proposed systematizing the rationing of scarce medical resources, like organs, based on a calculus of age and disability instead of first-come, first-serve. He also argued in opposition to the Hippocratic oath putting individual patients over cost and the greater good. These views were controversial, prompting some conservatives to suggest the ACA would instill “death panels’ (Forbes, 9/24/14).

Emanuel has been proposing a similar approach to who should receive COVID-19 treatment and vaccination. He proposes prioritizing individuals with greater social value and more estimated years remaining, which is calculated based on age and disability (New York Times, 3/12/20; NEJM, 5/21/20).

Several media outlets, especially the New York Times, have provided extraordinary and mostly uncritical space for Emanuel’s ideas on Covid, even though he is not an epidemiologist. He is also not the only member of Biden’s Covid advisory board. The Times has published 12 op-eds related to Covid written or co-written by Emanuel since the pandemic started (e.g., 4/14/20, 7/29/20)—more than the total number of Times op-eds about how Covid has affected disabled people and seniors. Emanuel has also written several Covid-related opinion pieces for the Washington Post (e.g., 4/22/20, 7/31/20), as well as for USA Today (3/19/20, 10/10/20), Science (9/11/20) and the Atlantic (4/18/20, 5/22/20) (for which he previously wrote reviews of DC-area restaurants).

Corporate media’s elevation of Emanuel and Singer as experts on COVID-19, without scrutinizing their troubling views, points to how unprepared news outlets are to report on the nuances of disability in the age of Covid. On November 7, many disabled people on Twitter were pleasantly surprised after CNN’s Jake Tapper mentioned “#cripthevote” on live television, a popular hashtag for disabled political conversation.

“This is not a community that gets a lot of attention as a political force,” Tapper said. About 25% of the U.S. population has a disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control, and this percentage is likely to have grown in the last year, with the rise in long-haul Covid illness.

Justine Barron is an investigative journalist who focuses on criminal justice, corruption and media in Baltimore. She co-investigated the death of Freddie Gray for the Undisclosed Podcast in 2017. She can be found on Twitter at @jewstein3000.