The New York Times (9/7/22) continues to present the Chinese government’s saving millions of lives as an unmitigated disaster.

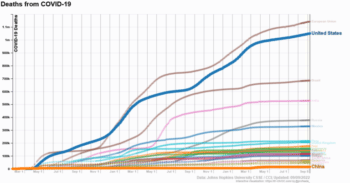

Four and a half million people.

That’s how many Chinese people would have died from Covid-19 had its government taken the same approach to the pandemic that the United States has taken, and gotten the same results.

Instead, China has had 15,000 deaths from Covid—most of these from an outbreak in the spring of 2022 in Hong Kong, which has its own healthcare system.

Meanwhile, the United States has lost more than a million people to Covid since the pandemic began. Deaths currently continue at the rate of about 450 a day, which would add up to roughly 160,000 a year if present trends continue.

Clearly China and the United States have very different systems, and what works in one place would not necessarily work in the other. But given the remarkable success that China has had in protecting its population from a deadly and pernicious virus, surely U.S.-based journalists are examining what lessons China has to teach us?

No, not if you work for the New York Times. There you’ll be writing yet another in a series of articles about how China has had the enormous misfortune of avoiding mass death.

“China’s ‘Zero Covid’ Bind: No Easy Way Out Despite the Cost,” is the headline of the latest iteration (9/7/22), written by Vivian Wang. The article begins:

Tens of millions of Chinese confined at home, schools closed, businesses in limbo and whole cities at a standstill. Once again, China is locking down enormous parts of society, trying to completely eradicate Covid in a campaign that grows more anomalous by the day as the rest of the world learns to live with the coronavirus.

But even as the costs of China’s zero-Covid strategy are mounting, Beijing faces a stark reality: It has backed itself into a corner. Three years of its uncompromising, heavy-handed approach of imposing lockdowns, quarantines and mass testing to isolate infections have left it little room, at least in the short term, to change course.

The New York Times maintains it’s the country with the orange line, not the dark blue one, that has the Covid policy problem.

Nowhere in the article is any comparison of the respective death toll in China and the U.S. Or any hint that life expectancy in the U.S. has now dropped below that of China—76.1 vs. 77.1 years, respectively (Quartz, 9/1/22)—an acknowledgment that would render ridiculous the Times‘ assertions that that China’s “government has pushed propaganda depicting the virus as having devastated Western countries,” and that President Xi Jinping “has prioritized nationalism over the guidance of scientists.”

But it’s not just the Covid death toll that the Times has to hide in order to make its anti-China spin remotely credible. Much of the piece deals with the hardship supposedly caused by the zero-Covid policy: “The social and economic cost will continue to increase,” insists one of the article’s relatively few sources, the Council on Foreign Relations’ Yanzhong Huang (author of the New York Times op-ed “Has China Done Too Well Against Covid-19?”—12/29/20—which argued that “China’s comparative success now risks hurting the country”).

Wang sure does make the economic situation in China sound grim:

Many Chinese have found ways to cope, even if reluctantly: putting in longer hours to scrape up more money, cutting back on spending. Complaints about a shortage of medical care or food often emerge, but some residents say they support the overarching goal….

Youth unemployment is soaring, small businesses are collapsing and overseas companies are shifting their supply chains elsewhere. A sustained slowdown would undermine the promise of economic growth, long the central pillar of the party’s legitimacy.

But what is the actual cost of China’s Covid success? In 2020, the first year of the pandemic, China’s GDP grew by 2.2%, while the U.S.’s shrank by 3.4%. In 2021, the U.S. economy bounced back, with 5.7% growth—but not as much as China, which grew 8.1%. Projections are for the U.S. to grow by 1.3% in 2022, while China is expected (by Goldman Sachs) to grow 3.0%.

When you add it up, China is expected to be 13.8% richer at the beginning of 2023 than it was when the pandemic began—whereas the U.S. will be just 3.4% better off. So which country’s belts need tightening as a result of its Covid strategy?

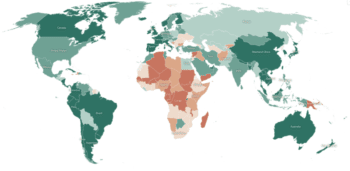

The New York Times (9/7/22) reported that China “suffered from low vaccination rates”—but a glance at the Times‘ own vaccination tracker shows that China in fact has one of the highest vaccination rates in the world.

The Times similarly had to suppress any comparative numbers to make it seem like China’s vaccination strategy was particularly dangerous:

Buoyed by its early success at containment, the party was slow at first to encourage vaccination, leaving many older Chinese vulnerable….

While other countries prioritized vaccinating the elderly, China made older residents among the last to be eligible, citing concerns about side effects. And it never introduced vaccine passes, perhaps sensitive to public skepticism of its own vaccines.

In late July, about 67% of people aged 60 and above had received a third shot, compared to 72% of the entire population. Medical experts have warned that an uncontrolled outbreak could lead to high numbers of deaths among the elderly, as occurred during a wave this spring in Hong Kong, which also suffered from low vaccination rates.

Go to a helpful page of the New York Times website called “Tracking Coronavirus Vaccinations Around the World,” however, and you’ll find that China isn’t “suffer[ing] from low vaccination rates”; it actually has one of the highest rates of Covid vaccination in the world, with 93% receiving at least one dose and 91% “fully vaccinated.” The latter number compares with 86% in Australia and South Korea, 84% in Canada, 81% in Japan and Brazil, 79% in France, 76% in Britain and Germany—and 67% in the U.S.

That last number, in China, is treated by the Times as a dangerously low percentage of the elderly to have received booster shots—but in the U.S., only 41% of those aged 65—74 have received booster shots, along with 42% of those 75 and over—and just 26% from 50—64. Isn’t the U.S. booster rate much more ominous?

Well, yes—and that’s part of the reason that tens of thousands of elderly people will die this year as part of the US’s effort to “learn…to live with the coronavirus.”