This article is part of ourEconomy’s ‘Decolonising the economy‘ series.

Mainstream politics in Europe and North America is increasingly divided into two hostile camps: on one side are conservative reactionaries who glorify imperialism and wish to resurrect it, on the other are avowedly progressive liberals and socialists who express varying degrees of shame about the past but deny that imperialism continues in any meaningful way to define relations between rich and poor countries. Even the debate on reparations for slavery and colonialism is framed in terms of correcting past wrongs, excluding any notion that imperialist plunder of nature and living labour continues apace in the modern ‘post-colonial’ world.

One reason for this myopia is that imperialism is confused with colonial occupation. Apart from the north of Ireland and occupied Palestine, colonies are a thing of the past, ergo the same is true of imperialism. But colonial rule is just one of several possible forms of imperialism; its unvarying essence is plunder—of human and natural wealth. Capitalism has evolved new and far more effective ways to plunder than by sending armies to ransack poor countries and butcher their people. Just as chattel slavery was replaced with the silent compulsion of wage slavery, in which workers ‘freely’ sell their labour to capitalists, so colonial plunder has been replaced by what is euphemistically known as ‘free trade’.

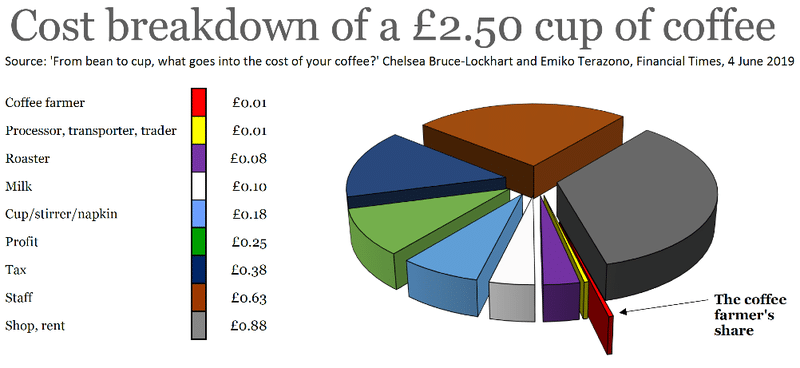

The costs of coffee

Consider, for example, a £2.50 cup of coffee purchased from one of the chains. Just 1p goes to the farmer who cultivated and harvested the coffee. In recent years the world market price for green coffee beans has plummeted and, at £2.00 per kilogram, is close to its lowest in history in real terms. For many of the 25 million small farmers who grow 94% of the world’s coffee, this is far less than the cost of production. Coffee farmers in Central America, for instance, need between £3.30 and £4.10 per kilogram just to break even, so they currently earn absolutely nothing for their hard labour and that of their children who typically help to bring in the harvest. Instead, they go deeper into debt; they watch their children starve; some turn to cultivating coca, opium or marijuana; many abandon their farms altogether and head towards the U.S. border or to vast slums surrounding swollen cities. Meanwhile, the capitalist firms that roast the coffee, almost entirely headquartered in Europe and N. America, see their fat profits get fatter still, while the cafe chains and the landlords from whom they rent their premises turn around half of the price of a cup of coffee into profit.

Meanwhile, the capitalist firms that roast the coffee, almost entirely headquartered in Europe and N. America, see their fat profits get fatter still, while the cafe chains and the landlords from whom they rent their premises turn around half of the price of a cup of coffee into profit.

The GDP illusion

Remarkably, all but 2p of the £2.50 cup of coffee counts towards the UK’s GDP. This is a particularly glaring example of The GDP Illusion, the amazing conjuring trick whereby wealth generated by super-exploited farmers and workers in plantations, mines and sweatshops across Africa, Asia and Latin America magically reappears in the gross ‘domestic’ product of the countries where the products of their labour are consumed. And they are super-exploited because, no matter how hard they work, they cannot feed their families or pay for essential needs like healthcare and education that workers in rich countries rightly regard as their birthright.

What’s true of coffee is, to varying degrees, also true of our clothes, gadgets, kitchen appliances and much else. For example, of the £20 paid to Primark or M&S for a shirt made in Bangladesh, at most £1 will appear in Bangladesh’s GDP, of which perhaps 1p will be paid to the garment worker whose 70-hour week will not earn enough to feed her children. Leaving aside the cost of the cotton raw material, the vast bulk of that £20 will appear GDP of the country where this product is consumed.

Around 40% of the final sale price will end up in the hands of the government—not just 20% VAT, but also taxes on the profits of the department stores, landlords and other service providers, and on the wages of all those who work for them. The government uses this money to pay for the army and police, the NHS, pensions etc. So, when anyone says “why should we let migrants use our NHS?”, they should be answered, “because they’ve helped to pay for it!” Unfortunately, no-one on the ‘left’ is currently saying this!

21st century imperialism

During what is known as the neoliberal era, from around 1980 onwards, capitalists shifted production of garments and many other items to low-wage countries. Their motive: to boost profits by substituting low-waged labour abroad for more expensive labour at home, thereby slashing wage bills while avoiding direct confrontation with their own workers. Much of what used to be called the ‘Third World’ was turned into a giant export processing zone producing cheap inputs and consumer goods for Europe and North America. As a result, profits, prosperity and social peace in rich countries became ever more dependent on super-exploitation of hundreds of millions of workers in poor countries. This must be called by its true name: imperialism; a new, modern, capitalist form of imperialism, one that doesn’t rely on crude techniques inherited from the feudal era—but which certainly does indulge in state terrorism, covert warfare and direct military intervention whenever necessary.

Not only did the global shift of production permit a restoration of profitability and a resumption of capital accumulation, it dramatically increased competition between workers across borders. In the economic struggle—the struggle to protect and improve one’s position within the capitalist system in contradistinction to the political struggle to overthrow it—seeking protection from increased competition is a natural and normal reflex. But this does not make it progressive! The other side of the coin to emigration of production to low-wage countries is immigration of workers from these countries. Hostility to immigration was the single-most important factor that induced most workers in Britain to vote against EU membership. Workers’ reflex response to increased competition—calls for walls to be built and borders to be closed—is the clearest possible example of what Lenin called “the spontaneous, trade unionist striving to come under the wing of the bourgeoisie.”

Evidence of the persistence and indeed pervasiveness of imperialism is all around us. Yet liberals, social democrats and even many who consider themselves revolutionary socialists are blind to this, helped by semantic quibbles about what ‘imperialism’ means, and hiding behind statistics that obscure far more than they reveal. Imperialism-glorification is detestable, but imperialism-denial is a much bigger obstacle to building a movement capable of overturning the dictatorship of the rich that lurks behind the increasingly tattered and discredited façade of democracy.