The Handbook of Marxism and Post-Marxism I co-edited with Alex Callinicos and Stathis Kouvelakis aims to present the development of Marxism as a militant tradition in dialogue with other traditions and within itself. Even if it was conceived almost six years ago, the multiple crises we are confronting today–economic, political, social, gender, environmental and biological–vindicate the spirit of our project. The project seeks to look at Marxism as a tradition that is rooted in and addresses the totality of capitalist social antagonisms and, by doing so, is able to think strategically beyond capital.

Several contributions challenge reductionist interpretations of Marx’s critique of political economy, and the idea that Marxism is irremediably Eurocentric and underestimates race, gender and ecology. This opens a space for a more complex, and I would say fertile, dialogue with Post-Marxists currents. The format of the Handbook–combining longer contextual essays and shorter essays on individual thinkers mainly–aims at facilitating this dialogue. We chose this format, rather than concentrating on themes and concepts, in order to capture the specificity of, and interactions between, individual thinkers and problematics.

In the final part of the book, “Marxism in an Age of Catastrophe”, John Bellamy Foster and Intan Suwandi forcefully argue that Marx inaugurated traditions of thought that can intellectually encompass the present age of catastrophe, announced by the floods and fires around the world as well as by the COVID-19 pandemic. These reflections complement the first part of the Handbook, “Foundation”, which points to the strong connection Marx and Engels posited between the critique of political economy and a politics of working-class self-emancipation. Thanks to this connection, they were able to conceive of capitalism as a global, gendered, racialized and ecological class antagonism in which struggles over wages and working conditions are organically linked to struggles over dispossession, social reproduction, ecology, imperialism and racism. Support for the demands of the most oppressed is thus crucial for the advancement of the working class as a whole.

Anti-colonial Marxism–beyond the Eurocentric stereotype

The popularization of Marxism in the wake of the emergence of mass socialist parties in late 19th Century Europe strengthened reformist and economistic interpretations of it. But Daniel Gaido and Manuel Quiroga challenge the commonplace idea that the Second International was Eurocentric in focus, presenting its heated debates on reformism, imperialism and national self-determination. While Rosa Luxemburg stood out for her anti-imperialism, Kautsky initially stated that socialists must support “all native independence movements” and condemned the idea of inevitable stages of history as stemming from “European megalomania” and racism (1907). Interestingly, the Italian Socialist Party, who expelled rightwing reformists who supported the colonization of Libya, was among the few sections of the International who did not follow Kautsky’s capitulation to chauvinism and support for the First World War.

The catastrophe of the Great War, along with the Russian Revolution of 1917, led to a “second foundation” of Marxism. This was both political, with the birth of the Third International, and theoretical: as Lenin notably said reading Hegel’s Science of Logic in the summer 1914, since no Marxist had seriously engaged with the Logic before, none had really understood Marx’s Capital. Hegel’s dialectic informed critiques of historical inevitability, as well as reflections on ideology, hegemony and revolutionary consciousness. In the writings of Lukács and Gramsci, Marxism was no longer understood as scientific socialism, but as the theoretical articulation of workers’ self-consciousness. Marxism also became a much more plural tradition, with the canonization of a new Marxist-Leninist/Stalinist orthodoxy in Russia, the revolutionary engagements of Gramsci, Bordiga and Trotsky, and the emergence of a current of Critical Theory, with the Frankfurt School, increasingly located in the academy but, as Henry Pickford shows, in constant dialogue with Marx.

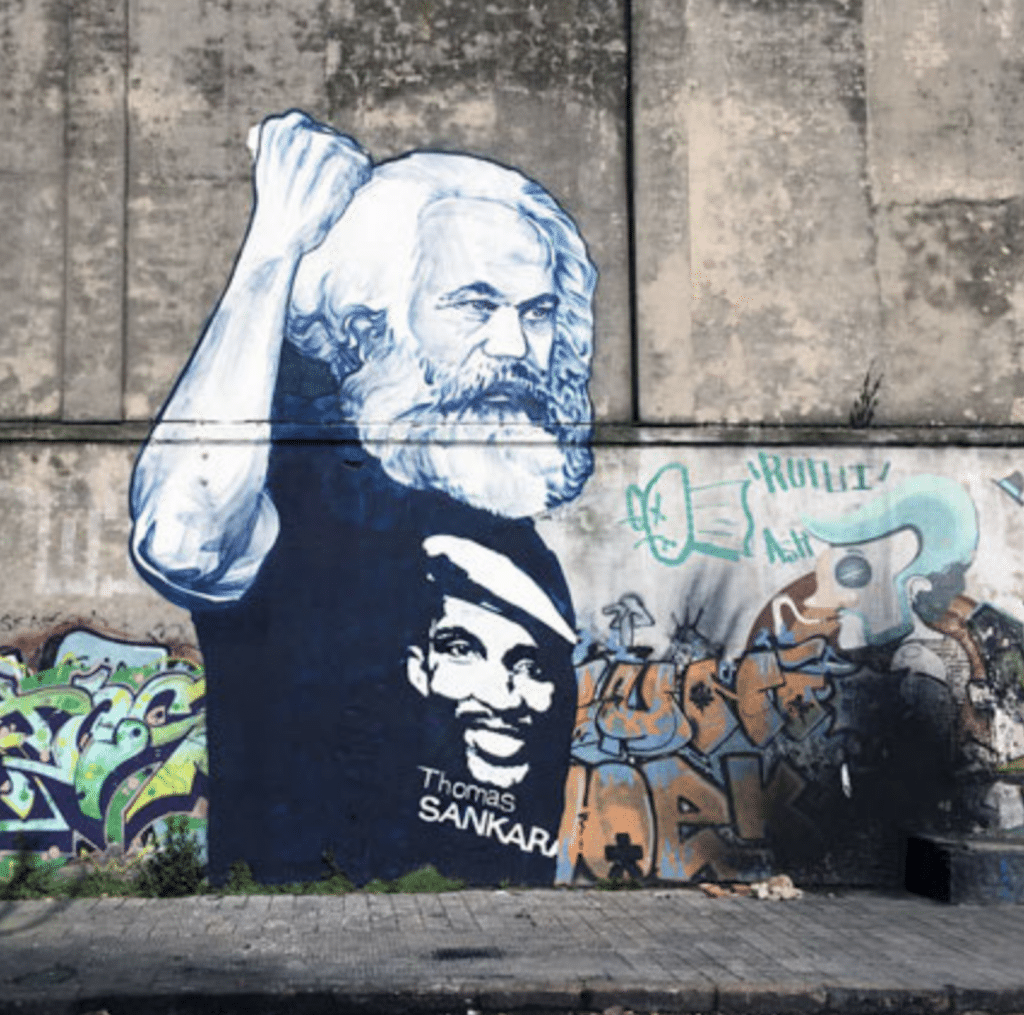

Vijay Prashad’s framing essay and the part it introduces on the Tricontinental powerfully challenge the assumption that theory, even Marxist theory, “is produced in Europe and in North America, while ‘practice’ takes place in the Global South.” Even during the Second International, from Ireland, James Connolly disputed stageist views of history, boldly proclaiming–and putting in practice as one of the leaders of the 1916 Easter rising–the inextricable link between the struggle for national liberation and the struggle for socialism. For the Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariategui this link meant drawing the history of indigenous anti-colonial resistance and the revolutionary anti-capitalist struggle together, in a “heroic creation” of socialism in Latin America. Energized by Lenin’s theory of national self-determination and the anti-imperialist programme of the first congresses of the Third International, many Marxists in the colonial or semi-colonial world–from Mao to CLR James, Tabata to Hadji Ali and Fanon–sought to break free of the strictures and dead-ends of Stalinism, arming the national liberation struggles towards socialism.

In their struggles, for Fanon, the colonized were “political animals in the most universal sense of the word”. Indeed, the anti-colonial revolutions challenged the global imperialist system, breaking the legitimacy of racial domination also in its core. There, the 1960s and 1970s saw a multiplicity of antagonistic forces–women, students and racialized groups–come to the fore of the political stage along with the working class, putting social revolution back on the agenda. Along with the Russian repression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956, as Frédéric Monferrand explains, these movements inspired a “renewal” of Marxism that now more strongly relied on Marx’s Capital–with the Neue Marx Lectuere, Tronti’s workerism and Althusser emphasizing the rupture between Marx and classical political economy and addressing, in very different ways, the practical issue of social transformation (or its impossibility, as in the case of the NML). Militant scholars like Samir Amin and Immanuel Wallerstein tried, in different ways, to overcome methodological nationalism and Eurocentrism within Marxism itself, contributing to the development of dependency and world systems theories.

The collapse of socialism and the rise of post-Marxism

But this international convergence of struggles was unable radically to overthrow the system. Instead, as Giovanni Arrighi argued, it amplified its structural crisis in the mid-1970s, unleashing the neoliberal offensive and accelerating the collapse of ‘really existing socialism.’ Despite the wealth of Marxist criticisms of the USSR before 1989, these developments were associated with a ‘crisis of Marxism.’ For Stathis Kouvelakis, the ‘Post-Marxism’ that emerged in this period treated the search for the unity of a ‘structured totality’ as irrelevant or even damaging, leading to an ‘eclipse of strategic reason’ (Bensaid). On the one side, the new readings of Marx’s Capital that had previously emerged had failed to explain the articulation of different forms of exploitation and oppression within global capitalism. On the other, in a context of political retreat, the heterogeneous forms of domination contested were seen as not fitting the ‘Marxist schema of class struggle,’ contributing to the rise of post-structuralism.

If, for some, a move toward a poststructuralist interrogation of Marxism was implicit from the very start of the Subaltern and then Postcolonial Studies projects, the essays in this Handbook show that their relationship to Marxism is not necessarily conflictual. This is particularly evident in the essay on Ranajit Guha and in the essay by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak that introduces the part “Unexplored Territories?” interrogating how Marx’s “intuition of totality” relates to the subaltern experience. The subsequent entries on Angela Davis, Lise Vogel and social reproduction theory, Stuart Hall, ecological Marxism, Huey Newton, and Chandra Talpade Mohanty and Third World feminism show the fertility of Marxism, and of traditions inspired by it, for contemporary struggles for racial, environmental and gender justice.

Marxist critiques of political economy and rethinking class struggle

The penultimate part of the handbook “Hidden Abode: The Marxist Critique of Political Economy” then relates contemporary debates among heterodox and Marxist political economists, and their different understandings of financialization and crisis, to the tensions within Marx’s value theory itself. The entries on Paul Sweezy, Harry Braverman, Ruy Mauro Marini and David Harvey point to the continuing and increasingly international debates about Marxist theories of imperialism, dependency, and revolutionary strategy. This part complements the previous one, “Unexplored territories?”, which shows the inherently gendered, ecological and racialized nature of contemporary imperialism, neoliberalism and the multiple crises we are facing today.

These crises raise, again, the question of social totality and strategic thinking. This Handbook pushes us to rethink reductionist conceptions of the class struggle. It shows that Marx and Marxism have never been concerned only with factory workers but have dealt with the ways in which capital accumulation is intertwined with continuing processes of ‘primitive accumulation’, which shape, and are shaped by, labour exploitation. Imperialism, dispossession and ecological destruction swell the ranks of the global reserve army of labour, which is both mobilized and trapped by new mechanisms of global apartheid, racialization and super-exploitation. This framework sheds light on the current age as an age of catastrophe as well as global revolt. If–as John Bellamy Foster, Intan Suwandi and Alex Callinicos explain in the last part of the Handbook–the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is the consequence of a globalized, imperialist system based on environmental destruction and deforestation, then peasant and indigenous struggles against marketization and dispossession are not separate from workers fighting for safe jobs, conditions and reproductive rights, or from struggles against imperialism, sexism, racism and racist policing. And it is on the terrain of struggle that the deeper unity between social production and reproduction comes to light, when diversity becomes solidarity, strength and political radicalism.

If, loyal to the history of Marxism, contributors to this Handbook share as many disagreements as commonalities, Spivak’s clarification, at the launch of the Handbook, that she’s not a Post-Marxist, she is a Marxist, made me think. In the new age of global revolt inaugurated by the 2011 uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa, the Black Lives Matter movement and the new Palestinian Intifada, retrieving the rich, global history of Marxism is even more important to think strategically about our future.

Lucia Pradella is Senior Lecturer in International Political Economy at King’s College, London. She tweets at @LuGuangMing.