Economic inequality is arguably the crucial issue facing contemporary capitalism—especially in the United States but also across the entire world economy.

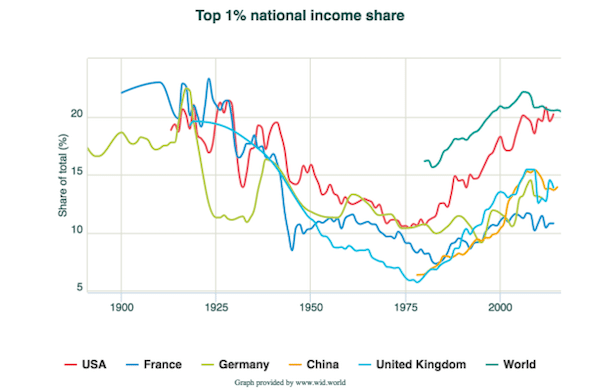

Over the course of the last four decades, income inequality has soared in the United States, as the share of pre-tax national income captured by the top 1 percent (the red line in the chart above) has risen from 10.4 percent in 1976 to 20.2 percent in 2014. For the world economy as a whole, the top 1-percent share (the green line), which was already 15.6 percent in 1982, has continued to rise, reaching 20.4 percent in 2016. Even in countries with less inequality—such as France, Germany, China, and the United Kingdom—the top 1-percent share has been rising in recent decades.

Clearly, many people are worried about the obscene levels of inequality in the world today.

In a famous study, which I wrote about back in 2010, Dan Ariely and Michael I. Norton showed that Americans both underestimate the current level of inequality in the United States and prefer a much more equal distribution than currently exists.*

In other words, the amount of inequality favored by Americans—their ideal or utopian horizon—hovers somewhere between the level of inequality that obtains in modern-day Sweden and perfect equality.

What about contemporary economists? What is their utopian horizon when it comes to the distribution of income?

Not surprisingly, economists are fundamentally divided. They hold radically different views about the distribution of income, which both inform and informed by their different utopian visions.

For example, neoclassical economists, the predominant group in U.S. colleges and universities, analyze the distribution of income in terms of marginal productivity theory. Within their framework of analysis, each factor of production (labor, capital, and land) receives a portion of total output in the form of income (wages, profits, or rent) within perfectly competitive markets according to its marginal contributions to production. In this sense, neoclassical economics represents a confirmation and celebration of capitalism’s “just deserts,” that is, everyone gets what they deserve.

From the perspective of neoclassical economics, inequality is simply not a problem, as long as each factor is rewarded according to its productivity. Since in the real world they see few if any exceptions to perfectly competitive markets, their view is that the distribution of income within contemporary capitalism corresponds to—or at least comes close to matching—their utopian horizon.

Other mainstream economists, especially those on the more liberal wing (such as Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, and Thomas Piketty), hold the exact same utopian horizon—of just deserts based on marginal productivity theory. However, in their view, the real world falls short, generating a distribution of income in recent years that is more unequal, and therefore less fair, than is predicted within neoclassical theory. So, bothered by the obscene levels of contemporary inequality, they look for exceptions to perfectly competitive markets.

Thus, for example, Stiglitz has focused on what he calls rent-seeking behavior—and therefore on the ways economic agents (such as those in the financial sector or CEOs) often rely on forms of power (political and/or economic) to secure more than their “just deserts.” Thus, for Stiglitz and others, the distribution of income is more unequal than it would be under perfect markets because some agents are able to capture rents that exceed their marginal contributions to production.** If such rents were eliminated—for example, by regulating markets—the distribution of income would match the utopian horizon of neoclassical economics.***

What about Marxian theory? It’s quite a bit different, in the sense that it relies on the assumptions similar to those of neoclassical theory while arriving at conclusions that are diametrically opposed. The implication is that, even if and when markets are perfect (in the way neoclassical economists assume and work to achieve), the capitalist distribution of income violates the idea of “just deserts.” That’s because Marxian economics is informed by a radically different utopian horizon.

Let me explain. Marx started with the presumption that all markets operate much in the way the classical political economists then (and neoclassical economists today) presume. He then showed that even when all commodities exchange at their values and workers receive the value of their labor power (that is, no cheating), capitalists are able to appropriate a surplus-value (that is, there is exploitation). No special modifications of the presumption of perfect markets need to be made. As long as capitalists are able, after the exchange of money for the commodity labor power has taken place, to extract labor from labor power during the course of commodity production, there will be an extra value, a surplus-value, that capitalists are able to appropriate for doing nothing.

The point is, the Marxian theory of the distribution of income identifies an unequal distribution of income that is endemic to capitalism—and thus a fundamental violation of the idea of “just deserts”—even if all markets operate according to the unrealistic assumptions of mainstream economists. And that intrinsically unequal distribution of income within capitalism becomes even more unequal once we consider all the ways the mainstream assumptions about markets are violated on a daily basis within the kinds of capitalism we witness today.

That’s because the Marxian critique of political economy is informed by a radically different utopian horizon: the elimination of exploitation. Marxian economists don’t presume that, under capitalism, the distribution of income will be equal. Nor do they promise that the kinds of noncapitalist economic and social institutions they seek to create will deliver a perfectly equal distribution of income. However, in focusing on class exploitation, they both show how the unequal distribution of income in the world today is affected by and in turn affects the appropriation and distribution of surplus-value and argue that the distribution of income would likely change—in the direction of greater equality—if the conditions of existence of exploitation were dismantled.

In my view, lurking behind the scenes of the contemporary debate over economic inequality is a raging battle between radically different utopian visions of the distribution of income.

Notes

*The Ariely and Norton research focused on wealth, not income, inequality. I suspect much the same would hold true if Americans were asked about their views concerning the actual and desired degree of inequality in the distribution of income.

**It is important to note that, according to mainstream economics, any economic agent can engage in rent-seeking behavior. In come cases it may be labor, in other cases capital or even land.

***More recently, some mainstream economists (such as Piketty) have started to look outside the economy, at the political sphere. They’ve long held the view that, within a democracy, if voters are dissatisfied with the distribution of income, they will support political candidates and parties that enact a redistribution of income. But that hasn’t been the case in recent decades—not in the United States, the United Kingdom, or France—and the question is why. Here, the utopian horizon concerning the economy is the neoclassical one, or marginal productivity theory, but they imagine a separate democratic politics is able to correct any imbalances generated by the economy. As I see it, this is consistent with the neoclassical tradition, in that neoclassical economists have long taken the distribution of factor endowments as a given, exogenous to the economy and therefore subject to political decisions.