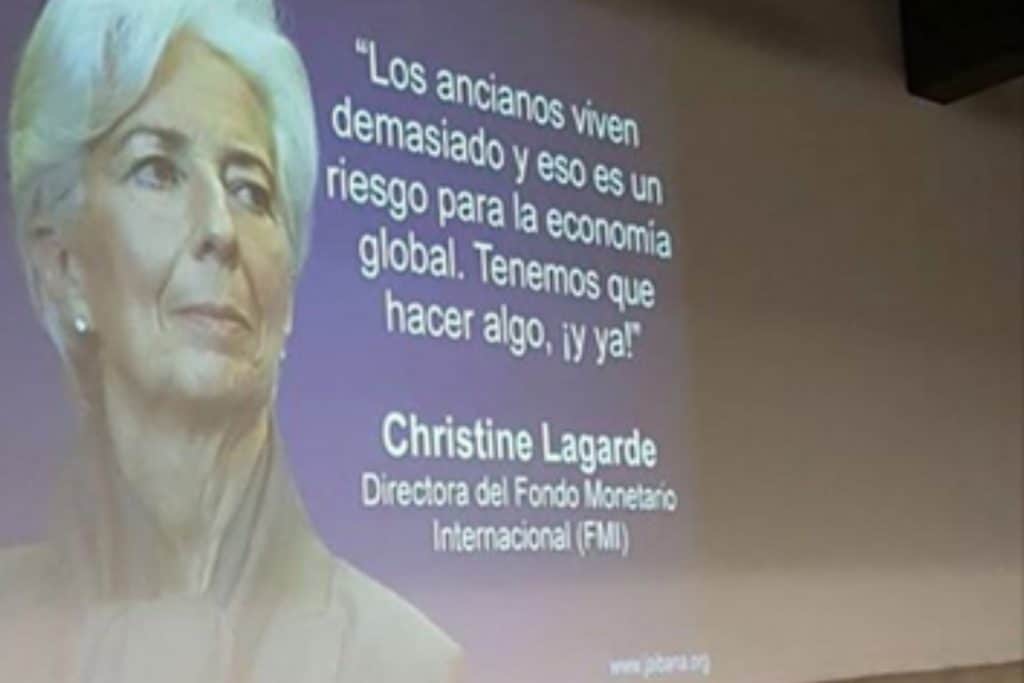

Old people live too long and this is a risk for the global economy. We must do something, urgently.

—Christine Lagarde, Director of the International Monetary Fund

(Translated from the Spanish)

This secret memo was discovered in the waste basket of a high-ranking staffer in the European Commission. It was sent to us by Dr. Margaret Morganroth Gullette, author of Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017).

The memo from “the Coalition” begins “Dear Angela, Teresa, Emmanuel…” and has a further list of first names (heads of state and secretaries or ministers of finance, health and human services), mostly scribbled over with marker. Monthly Review is pleased to be publishing this important leaked document here for the first time.

—Eds.

FOR YOUR EYES ONLY

Here at the Coalition we were impressed by Christine’s bravery, saying publicly that old people “live too long” and those in charge of the global economy must do something about it, urgently. Recently, a photo of her, with potentially incendiary language from her speeches, has gone viral, without raising any resistance.

Since older people do vote more reliably, her implication that old people are “superfluous” and “expensive” would seem troubling for the stability of political elites. But since then, Christine has kept her job while continually stressing the same themes, so it’s clear that the Americans who dominate the International Monetary Fund feel it’s safe to sow doubt on the need for knee-jerk protection of old people’s interests. This they have demonstrated vividly many times since the 2016 election. At Davos everyone was repeating the message.

The Coalition welcomes this new moment for advancing our sensible coordinated agenda toward the superannuated, increasingly justified as all our budgets are swallowed up by entitlements, our streets and ICUs are clogged with old people, medical expenses for the senile are soaring, and adult children are burdened with costs and guilt.

While exploiting this opening for positive action, however, nota bene, this encrypted memo is not for distribution. Its frank and open discussion of the graying nations problem means holdings its suggestions within a tight circle. Please print and delete.

Lagarde gets away with promoting our policy recommendations by doing the numbers on longevity. Numbers don’t lie. Our advice is to advertise the magnitude of the problem by evoking the dire situation of Japan. Their data scares other nations into compliance with raising the age of retirement and cutting entitlements. Helpfully for us in the U.S., the Alzheimer’s associations already publicize the data we need. Repeating the percentages of old people alive now in your country, and projecting the appallingly larger numbers in the future (2040 or 2050), along with the percentages of dementia cases now and later, is a fool-proof tactic for creating fruitful anxiety and underscoring the need for dramatic bipartisan responses to the crisis.

Some wimps and wets will complain about “ageism” but the good news is that this charge does not matter. Few people in any society know the term. In Spain, they use the English loan-word, “ageism.” In the U.S., a recent study shows that ageism comes last in a list of the other “isms” people are concerned about, after sexism—sexism now, with the #MeToo movement and the circus around Justice Kavanaugh, has risen to the top of the list—and then racism and homophobia. Ageism is simply not seen as an oppression. In the U.S. the Supreme Court has not added age as a protected category, and indeed has denied midlife workers some of the blanket protections of the 1967 Age Discrimination in Employment Act. When asked, old folks often say ageism refers to young people offering them a seat on the bus. Or that it refers to words, like “wrinklies” (in Britain) or “geezer” (in the U.S.). Letters to the editor or columns that battle over how to respond to trivial nomenclature issues are a useful distraction from our economic agenda.

Those of you in the U.S. deal with the entire FDR legacy; others confront the postwar socialist consensus that Margaret and Ronald, gutsy as they were, barely began to dismantle.

Progress on our agenda has been made since the 1980s. It now seems quite possible to reform the safety nets further without attracting undesirable attention. Although older people vote, they seem unable to unite to defend themselves. “Raising the deficit” is a nonpareil strategy, enabling many governments to target national health systems they really must reduce. The U.S. tactic of repeating that Social Security and Medicare are soon to be insolvent, and that people who are young now will not benefit in old age, is proving successful.

For years we have clearly stated that reducing expectations would work. Calling anger at inequality “divisive class warfare” is a recommendation we support, now that unionization has been discredited for providing over-paid jobs for subordinate groups who clearly do not merit special scrutiny. We suggest that as inequality rises, you divert attention from class envy to age-related Schadenfreude, pitting generation against generation. In comment sections and op-eds, young Americans, without being paid to say so, voluntarily deride anyone trusting in U.S. Treasury bonds. They angrily turn on the aging Boomers, who they firmly believe will be the last generation to receive benefits. This belief leads to inaction. We intend to make this belief a self-fulfilling prophecy.

We foresee progress on other fronts. In the U.S., the Republicans are cutting some belly bloat by trimming rural offices of the Social Security Administration. Some cautious souls briefly argued that cutting services does not save enough money to counter the nuisance value of having longer phone wait times and fewer and more distant offices, which court media complaints and irate letters to editors. Still, it is a useful model of inserting invisible thin wedges when trying to destabilize the “third rail” of American politics, as Social Security used to be called. No longer so electrified, we are happy to note. Then-candidate Donald Trump, for example, promised again and again during his campaign to defend the FDR legacy programs. Promises seem all that is necessary to sway the electorate.

Medicaid has been next. Cutting off people who don’t work, the first move in Arkansas, has dropped all but 2% off the roles. This provides savings for a well-run state to use for more productive citizens (an ever smaller group, as robotization and computerization take over). Cutting back on protections for people in nursing homes is another U.S. tack.

For at least a decade, however, our Coalition anticipates, entitlement reformers will have to take into consideration older people who become homeless, because the press is becoming surprisingly alert on this score. The unusually cold weather last winter has been at fault here.

Old men who become suddenly homeless can be portrayed as the victims of their vices. But demented old women on street corners begging or crying will almost certainly need a different publicity campaign to make this seem inevitable. The trope of the unwelcoming Boomer daughter, perhaps? The problem is that old women, although they live longer, retain some prestige as mothers and grandmothers and thus present the main public-relations difficulty in this sector. We have been suggesting using ungendered terminology, like “old people.” Since everyone knows old people are sexless, this usage is not likely to be noticed, let alone attacked.

The Coalition has decided to focus special attention going forward on longevity, the bugbear of the rational modern state. The medical and scientific establishments boast about it as their success, and they cannot and should not be stopped from doing so, or the whole notion of pharmaceutical and surgical progress is thrown out the window. Imagine the outcries of the Big PhaRMA lobby and the medical associations were any health minister to complain about life expectations rising. Yet that rise is the problem we face as long as collective answers to social problems persist. Remember what Margaret taught us all to say. “There is no such thing as society, only individuals.”

Seizing the moment, Consortium thought-leaders have decided to tackle the challenge of making “longevity” itself seem a negative outcome. The press and publishers have needed no impetus from us—except the indirect incentive that some of our funders own them—to let authors and journalists demonize Alzheimer’s patients, and, despite the denials of a few gerontologists who have somehow become public figures, to equate Alzheimer’s and old age. This is the best advertising for our position.

Funded by many of you with generous donations, this campaign by the Coalition will continue to devise humane and unobtrusive ways to reduce the vast number of the superannuated in the advanced economies. Some pensioners retire abroad to low-income countries, emptying our streets and turning over housing stock to younger people, but, on the other hand, spending their disposable income as consumers elsewhere. Those who remain, more frequently live with their own kind, out of sight, and stay inside, properly respectful of the needs of young people to talk and walk rapidly on the public sidewalks on their way to perform their essential tasks without having to worry about running into slow confused codgers.

We continue to urge the expansion of the “overtreatment” meme—overtreatment as a harmful and unnecessary expense. In many countries the campaign against overtreatment in hospitals and medical practices is solidly underway. Doctors are warning about the risks and lower quality of life of later-life medical interventions. The press once again voluntarily help whenever they link the emotional term “burden” to the gross expenses of care.

Note to media moguls: feel free to risk more. Time published one man’s complaint about the cost of his mother’s $100,000 heart operation, even though the mother lived another ten years. The commentary that serves best is of the “I wouldn’t want to live past 75,” type—exemplified by Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, who called his own father at age 77 “sluggish” after his heart operation and said he would not want to be remembered as sluggish. His authority as a bioethicist in the National Institutes of Health gave him a free pass. Barack Obama, talking about his own grandmother to the New York Times, lamented the expense of end-of-life care. Editors can be encouraged to publish adult children’s unhappiness with the national costs of caring, especially if the writers have relatives said to be senile or close to death. The next economic crisis—not that we expect one—will facilitate more such poignant worries.

During this campaign, we warn public figures to use caution and display positive sentiments, always, when alluding to the horrors of later life and the diseases of seniors. It’s easier to let younger people do the negative work. Nowadays, many more are eager to say openly they will refuse “to be hooked up to machines.” “I’ll die before I get that way,” they say. We, of all people, rife with pro-life, as i like to say, should set a respectful tone toward “dying with dignity.”

Data may never be forthcoming about the effectiveness of emphasizing surgical “overtreatment” on reducing medical costs, but I can attest that it distracts from other costs that many of our allies in Big Pharma prefer the press and public not get into. Moreover, people are becoming convinced that there is a duty to die—a duty they feel toward their children of course, rather than the state.

As long as (costly) overtreatment remains the target of choice in the mainstream, as long as the acquiescent press likens Alzheimer’s patients to zombies, as long as editors publish the very natural concerns of adult children about the soaring costs of parental medical choices, as long as every economic downturn or voluminous tax cut produces deficit worries and increased long-term unemployment, this trend toward demoralizing generation after generation about getting old will grow.

In reducing the numbers of the supernannuated, people in their middle years who have become permanently unemployed have been committing suicide in increasing numbers, some from opioid overdoses, according to several reports from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. So-called deaths of despair among older men have become common. Old women, despite fearing becoming burdens to their children, hang on. In response, the Consortium suggests that age-shaming, to which older women seem more easily prone, may be the simplest means by which to achieve…

In reducing the numbers of the supernannuated, people in their middle years who have become permanently unemployed have been committing suicide in increasing numbers, some from opioid overdoses, according to several reports from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. So-called deaths of despair among older men have become common. Old women, despite fearing becoming burdens to their children, hang on. In response, the Consortium suggests that age-shaming, to which older women seem more easily prone, may be the simplest means by which to achieve…

[Here the text ends, the rest of the paper apparently having been ripped off.]

© 2018 by Margaret Morganroth Gullette.