Bavaria, Germany’s largest state, borders on Austria: both have countless Alpine peaks, lots of men in lederhosen, and many right-wing Roman Catholic traditions. Both had elections on Sunday. Before nightfall many an otherwise happy yodeler showed tightly compressed lips and a grim look.

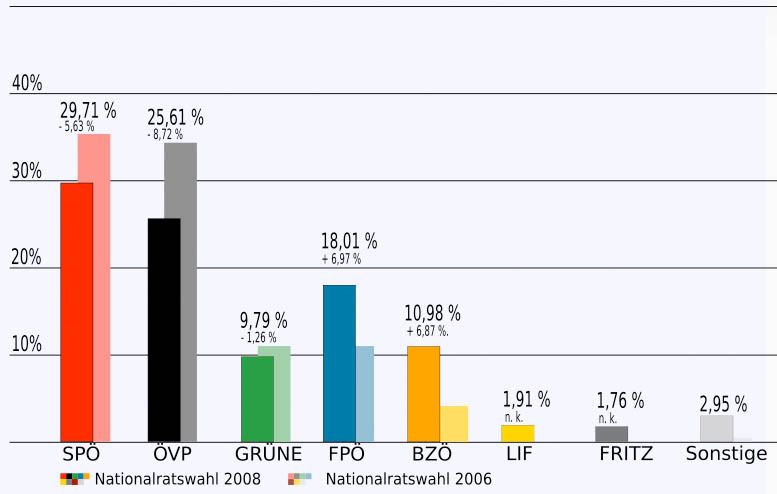

In Austria the main parties, the conservative Austrian People’s Party and the lukewarm Social Democrats, had maintained an uneasy coalition until July, when the former quit, forcing the new elections. It paid dearly for this, losing severely and getting only 25.6 percent. The Social Democrats also lost, nearly 6 percent, and though they remained the strongest party, with a total of 29.7 percent, another unhappy coalition between the two, as in Germany, may well be the weak result.

The true winners, now beaming broadly with their crooked smiles, can afford to yodel. Both extreme right-wing parties — the smaller one led by the notorious demagogue Joerg Haider, the other by an equally bigoted man named Heinz-Christian Stracke (their split was more about personality issues than policy) — climbed from under 16 percent in the last election to an alarming 29 percent this time. If they should reunite they would be the strongest political force in the country. Their success was due to general dissatisfaction with the two main parties, a lack of enthusiasm about the European Union, which the government had favored, but most of all, their ranting against foreign immigrants, the same racist strategy increasingly and dangerously menacing North America and most of Europe. In addition to their usual “Hate Immigrants” slogans, these right-wing extremists have been trying to seem somewhat less fanatic while calling for social improvements so as to appeal to working-class and middle-class voters. This paid off, and it is still possible that one or both might be invited to join a new coalition. Nothing is certain as yet.

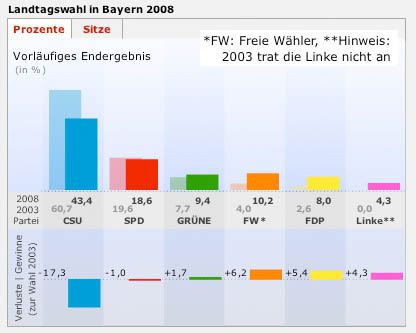

Bavarian voters also caused a sensation. For over 40 years this South German state, where Munich and Nuremberg are located, was run by one single party, the semi-autonomous sister party of Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union; in Bavaria it calls itself the Christian Social Union (CSU). Older newspaper readers may recall its blustering, controversial leader of past decades, Franz-Josef Strauss. Its current leaders, no less rightist in their thinking but lacking his tough oratorical skills, suffered a crushing defeat. From 60 percent in the last state elections they were reduced to 43.4 percent, thus losing their absolute majority and suffering the biggest such drop in post-war history. Though still the largest party they must now seek a partner to gain over half the seats in the legislature and thus stay in office. Their likely choice will be the equally reactionary but secular Free Democratic Party which, despite a few remaining libertarians from earlier years (it is still referred to as the Liberal Party), is even more pro-big business.

The Social Democrats did not profit at all from the losses of their traditional opponents, getting only 18.6 percent, their worst result in history. Their only thin joy after the Sunday vote was schadenfreude — satisfaction at the loss of the others.

But The Left, the young party which finally broke through the 5 percent hurdle in four West German states in the past year, failed to make it in largely rightist Bavaria. It would have taken a miracle to succeed here, too, and delegates to the founding convention in 2007 had laughed when a main leader, Gregor Gysi, joked about such an incredible possibility. A small but growing number of adherents fought hard, however: they were able to nominate candidates in all of Bavaria’s many towns and counties, and they campaigned on the issues everywhere, from rustic Alpine nests to industrial centers on the shores of the Danube. They hoped against hope, but in the end received 4.3 percent, good in Bavaria, but seven tenths less than required. “Better luck next time” was all they could say, and work for increased results in the national elections next year.

Thus, as in Austria, votes lost by the main right-wing party, the CSU, did not go leftwards. Luckily, they did not go to the extreme right, the neo-Nazis, either, but rather to the Free Democrats, to some degree to the Greens (with 9.4 percent), and to the Free Voters’ Initiatives, loose groups, mostly split-offs from the CSU, which campaigned largely on local issues. They got a surprising 10 percent.

It would seem that Bavarians are worried about problems like jobs, schools, wages, and prices, they are disappointed by both the two main parties, but are looking neither leftward nor to the extreme right for solutions.

Things looked rather different in Sunday’s elections in the East German Brandenburg, the state surrounding Berlin. The vote here was for city and county councils and mayors, and results varied widely. In the capital, the old Prussian stronghold of Potsdam, The Left pushed past the Social Democrats (SPD) with a score of 31 to 27 percent. In Frankfurt on the Oder, long a Left stronghold, it got 37.4 percent to 20.8 for the SPD and only 17.7 for the Christian Democrats (CDU). In Cottbus the SPD won the mayoralty; in the town of Brandenburg a Christian Democrat remained mayor. In the state as a whole, this party of Angela Merkel took a beating, landing in third place to the SPD and The Left, which are still neck and neck, with only a thin lead for the traditionally strong SPD.

And the neo-Nazis? As in Austria, they have two parties here, but the two cooperate and divide any spoils. One of them got 1.8, the other 1.6 percent, which does not sound like much, but enabled them (with no 5 percent hurdle in local bodies) to get seats in all but one of Brandenburg’s 14 counties, and in the city councils of Potsdam and Cottbus. Though only 1, 2 or at most 3 seats, this was enough to make trouble and work for further gains in coming elections.

Angela Merkel is still quite popular on a national scale, but her party (or its Bavarian sister) took heavy beatings in Bavaria and Brandenburg, while the Social Democrats were stuck at much the same level as before their recent leadership crisis. The Left was able to move forward, but needs more street action outside the various local and national legislatures if it is to buck the unchanging maltreatment by the media and nasty attacks by the established politicians of all other parties — and offer genuine solutions to harassed, threatened, or jobless working people, especially younger ones, who are being wooed by the neo-Nazis. More state elections are due early in 2009, but most suspense now (after watching the outcome of US elections) is directed at the vote for the European parliament next year and, most of all, the national Bundestag elections in a year’s time.

September 29, 2008

PS: According to later news, a special election held in the East German city Schwerin was won by the Left candidate, Angelika Gramkow. The former mayor of Schwerin, capital of the northeast German state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, was voted out of office after a scandal following the death by neglect of a young child and the off-handed treatment of the case by the local government and mayor. Six candidates competed to succeed him; the run-off between the two front-runners was on Sunday. The result was very close, 50.5 to 49.5 percent. Schwerin with its 100,000 inhabitants will be the largest city in Germany governed by a mayor from the young Left party.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

|

| Print