| “Our community is expanding: MRZine viewers have increased in number, as have the readers of our editions published outside the United States and in languages other than English. We sense a sharp increase in interest in our perspective and its history. Many in our community have made use of the MR archive we put online, an archive we plan to make fully searchable in the coming years. Of course much of the increased interest is from cash-strapped students in the metropolis, and from some of the poorest countries on the globe. For those of us able to help this is an extra challenge. We can together keep up the fight to expand the space of socialist sanity in the global flood of the Murdoch-poisoned media. Please write us a check today.” — John Bellamy Foster

To donate by credit card on the phone, call toll-free: You can also donate by clicking on the PayPal logo below: If you would rather donate via check, please make it out to the Monthly Review Foundation and mail it to:

Donations are tax deductible. Thank you! |

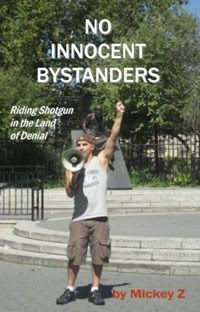

MZ: No Innocent Bystanders is the culmination of years of articles, essays, blog-posts I wrote while my mom was very ill. She passed away earlier this year. I began to feel that if I put some of these together, they might become a book.

People who run websites have said to me, “I’m not going to post this or that article because you’re blaming the victim.” But I tend to see the victims as the people under the bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan, as opposed to Americans paying for those bombs but choosing to ignore how their tax dollars are spent — not excluding myself.

As our situation becomes more drastic, I find my writing becoming less forgiving, hence the title. A lot of people say, “Well, people just don’t know,” but there comes a point where you have to ask, “When are we going to try to make a difference?”

SD: “No Innocent Bystanders,” makes me think of the Holocaust.

MZ: Actually, people who lived in Germany in 1936 had far more of an excuse to say, “I didn’t know what was going on” than today, with the Internet and cable TV. In this day and age, one click on your mouse, and you can see the direct cost of our actions, our inactions, our silence. You wonder what it’s going to take before people begin to step up.

SD: But how do you step up? That’s the huge question.

MZ: Act as if the planet is in critical condition. Think to yourself: with 200,000 acres of rainforest gone; 100 animal and plant species gone; 13,000,000 tons of toxic chemicals released every day — what are we going to say in twenty years? That it was more important to watch American Idol?

It’s great to have diversions, but how do we explain this inactivity, when we know the information? It’s amazing how many people on the Left can have a detailed knowledge of, say, what Bush and Cheney did, but not a knowledge of 80% of the world’s forests, or 90% of the large fish in the ocean, being gone — something like that is too huge to confront.

They’ll come out and protest for impeachment — which is valuable; I’m not denigrating people who put out these efforts, and I think every bit of solidarity has some value — but people keep following the same protest paradigms. The stakes are higher, and the other side learned better than the activists how to co-opt dissent; how to commodify it. There’s no greater example of that than of President Barak Obama.

But there are lifestyle choices. A recent article I did talks about how a person wakes up in the morning and flicks on a light, never thinking where the electricity comes from. I give talks about how companies blow off the tops of mountains in Appalachia to get the coal, and they dump the waste into the rivers below. It’s called “valley fill,” and it pollutes the entire area. For generations, people die of cancer, the river is polluted, because we flick the light on to have a conversation in a room. Every choice we make, every single choice, has a cost. We need to examine those choices — but not from guilt.

People say: “You’re attacking my lifestyle.” First of all, our lifestyle is worthy of attack; second, I’m saying, get rid of the guilt. Don’t make it about you: “Oh, I feel bad; I’m responsible.” The idea is to feel more empowered in making the small choices, then link with others making those choices.

“What can I do?” is a common question I get at talks. I say, “Look into your heart to decide what you’re willing to do and where your gifts lie. Don’t be so quick to rule things out, because situations can put you where you might use a tactic you never thought of before.”

Bringing it down to a microcosm: If you saw someone close to you being attacked, you might rush in and violently defend them. In the same breath, you might defend yourself as a pacifist or a nonviolent person. But there’s no other choice at that moment. That analogy perhaps could help you keep your eyes open to doing things you never imagined you were capable of. Not necessarily violent, but more drastic.

SD: But some people who took “drastic” action are in prison for a long time. There’s former Black Panthers who’ve been in since the 70s; more recently, activists from the Earth Liberation Front, whom you quote admiringly [“We have one message for the Obama administration: act to protect the environment or ELF will”]. Shouldn’t we connect imprisoned activists with people outside who are doing “acceptable” activism?

MZ: I agree. America doesn’t have many successful movements, but there’s women’s suffrage; anti-slavery; civil rights; labor unions. They succeeded in part because they once employed tactics outside what was accepted. We need to figure out what these tactics can be in 2008, 2009, because the stakes have never been higher.

Lately, I’ve been reading and writing a lot about Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal. These people are still in prison, with a mountain of evidence saying, at the very least, they didn’t get fair trials. I’m not going to sit here and say, “I know exactly what happened on that night. . .” But you can see there was a fair amount of railroading going on.

Groups like ELF can play a role in showing how far people are willing to go to protect their ecosystem and land base. When I look at property destruction, who am I to say they can’t pursue that? I’m not supporting them to go kill other human beings, but when you think about the symbolic gesture of property destruction, it goes all the way back to the Boston Tea Party. We celebrate that, but ELF are “terrorists.”

America has no shyness about violence, including the people running the show now who say, “We refuse to take the nuclear option off the table against Iran” — meaning Obama and Hillary. We’re encouraged to be nonviolent because it’s easier to manage people, and we’re given enough creature comforts so no one’s willing to risk much. Anyone who steps outside the realm of accepted activism is demonized.

SD: How did a working class kid from Astoria get into veganism, rainbows, and rad-lib politics?

MZ: I can sum it up in two words: Bruce Lee. I was a bit of a troublemaker when I was younger, and the martial arts calmed me down. I learned about Bruce Lee, who was far more than his movies. He was the original outsider who went on this journey of educating himself. He inspired me physically to strive for this ideal. He used to say, “Take what is useful and develop it from there.” I think Mao said almost the same thing. Once you challenge one tradition, everything else comes up for grabs.

The Astoria I grew up in was extremely blue-collar, and the time period was far more provincial than it is now. I had a very bossy older sister, and she would come home from first grade and force me to learn everything she learned. So I was reading at 4. And my uncle lived in the same walkup tenement as us. He was always inspiring me; he would give me an LP record of Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds, and say, “Check this out.” I was fortunate to be encouraged to educate myself about a variety of things.

I just always had an anti-authority bent in me. I went to Catholic school and the nuns would get mad at me. They’d say, “When are you going to live up to your potential?” But I was never motivated to be this 9-to-5, earning-lots-of-money type of person. I had this curiosity about what else was going on. Someone turned me on to Guy Debord and the Situationists — my jaw dropped. Some of it’s unreadable; I couldn’t figure it out — but the basic concept was so remarkably clear. Ultimately, somebody else told me about Noam Chomsky, and I had this epiphany — there was this whole different perspective out there. At that point, everything was open — everything.

Also Michele, my wife and partner, is very open. We’ve become vegan; we went in that direction together. We both came from provincial backgrounds where we could have been very mainstream, but we had different spirits. She and I have grown together in that sense, encouraging each other.

Finally, I had very compassionate parents. They always did the right thing for people around them. They led by example. I’ve had lots of happy accidents, the greatest of all being born to my parents, because, even though we differed politically, the environment they created for me was where it all started. I always felt — subconsciously, and now more consciously — that there can be a fundamental morality you live by: It’s keeping things as basic as possible.

I never totally bought into the Rambo thing. Maybe for a little while — because it’s hard, when you’re a young, white male in New York City, to not have that chauvinism — but you got to fight that down. It rings hollow at the end of the day, when we hear all these justifications about why we would carpet-bomb a country from 15,000 feet. But underneath are people just like you and me.

SD: How do you make your living?

MZ: I do personal training. It’s steady, and that’s been my primary source of income for decades, now, kickboxing and so on. I’m up every morning, 5:00 o’clock, going into the City, training clients, because they all want to learn martial arts or fitness before work. I also write for websites that actually pay. I do environmental blogging — any extra writing money I make, that’s awesome.

SD: What about heroes? Got any?

MZ: I shy away from the concept of “hero.” It romanticizes people or makes you feel that you couldn’t be like them. But I’m constantly inspired by people — my parents, obviously. My wife works in a nonprofit school. She’s a physical therapist with disabled pre-schoolers. That’s heroic to me, spending your day teaching a kid how to walk.

In a stricter political sense, someone like a Chomsky or a Howard Zinn — they give you life-changing moments. When you’re blue-collar, didn’t go to college, grew up in Queens, and read The People’s History of the United States, it’s got to change your life.

And people in the arts that challenge the standard, like Jackson Pollock. He painted, but at the time, it didn’t look like any painting that ever existed before. Or the be-bop musicians — that whole time period, really, the Beat writers, and the Brando generation of acting. You take an existing art, where you think it’s all been said and done, and then change it. I find that fascinating.

I think about what Rachel Corrie did — she put her life on the line. When people don’t show even an ounce of compromise in their stance, it’s utterly inspiring. I don’t think everybody has to be Rachel Corie, but it’s a shame that what happened to her hasn’t inspired more people.

There’s a bunch of folks who come to my website, calling themselves “The Expendables.” In fact, my book is dedicated to them. One of them started a website dedicated to the concept of animal extinctions. This is, on some level, heroic, because anybody who chooses to use their time and skills in this way — on a planet that’s so profit-driven — is almost revolutionary. We’re so bombarded with “Just Do It” and “Have It Your Way,” that when someone says, “I’m going to spend X amount of hours a day in the hope of waking people up,” that’s amazing.

I have another friend who does a website called “Tiny Choices.” It’s exactly what it sounds like: inspiring people to make little choices every day, mostly in the realm of environmentalism. This person could be channeling her skills and time in a multitude of moneymaking ways, but she chooses to do this. I have to call that heroic, because so much in our society encourages us to idolize the Bill Gates and the Donald Trumps, who’ve made billions. If people pay attention to efforts like this, they could change the world.

And I admire Arundhati Roy, who can give a talk filled with statistics, but it’s so lyrical. She keeps things on a human level where it’s not above anybody’s head. It’s really love-your-neighbor stuff, but on a political scale.

SD: Is “love your neighbor” the basis of your politics, then?

MZ: When you strip it down, yeah. We need to strip things down to a new foundation. When John Lennon said, “All you need is love,” I don’t think he meant that if you just loved Bush and Cheney, they would stop. What’s he’s asking is, where does it start — on what foundation?

I think about what I’ve personally been through in the last couple of years, with my mom sick and her passing away. It was more than anything I could have imagined, to go through that grief and mourning. It’s a billion times worse; no matter how prepared you think you are.

Then I look at what happened the day before the election. When everybody’s celebrating the ascendancy of this corporate Democrat, the U.S. Air Force blew up a wedding in Afghanistan. Forty people dead, 28 injured, including the bride. Why do we relate more to the people who dropped that bomb than to the people at that wedding? When was it decided that their lives matter less than ours?

Perhaps, on some level, it’s just being human. It’s about saying that people at that wedding party in Afghanistan on the day that Obama was elected are far more important to me than Obama being elected. And they should be more important to us.

If anything, Obama will step up the war in Afghanistan; he’ll do nothing to stop bombs hitting weddings. When are we going to do something to stop that? How would we feel if it was our daughter or our sister gone in an accidental bombing? That’s what attracts me to Arundhati Roy’s work; it’s what I strive for in mine, with a lot more cynicism and sarcasm.

Thomas Paine said, “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.” It doesn’t get any more fundamental than that. You have to remember the species that are going extinct; the wedding that’s being blown up. Because (A) we all play a role in that, and (B) if we let that continue, even for self-preservation, it’s going to come back to us all, sooner or later. It’s frighteningly close now.

SD: Your book may be sarcastic and cynical, but I feel an underlying sense of mourning in it.

MZ: I don’t know if I could have written with that depth of sorrow had I not gone through the death of my mom. I feel at times an immense sadness about the world; that we’ve been given these amazing gifts as human beings, and we’ve done almost everything wrong — when it could have been so different.

But I think there’s a positive in that mourning. It’s crucial to remember that we can be despondent and motivated at the same time. Or we can be outraged and happy at the same time. The human mind is so complex.

People who’ve only read my articles and haven’t met me might think I’d be a rather grim person. That’s nowhere near the case — there are things about my life that are absolutely wonderful. I don’t want to walk around so guilty about the American lifestyle destroying the planet that I become unbearable to everyone around me; I want to be an example of somebody who can know this stuff and not be beaten by it.

It’s all about perspective. Proust said something about seeing the world with “new eyes.” You can look at these horrors going on with a sense of epiphany: “Wow, I have such a purpose right now.”

So, instead of training like a lunatic to climb the highest mountain or run the fastest in the Marathon or make your first million before you’re thirty, could you imagine this goal: To leave the planet better than when you got here? What greater goal could you possibly have in the world?

My hope for this book is that people come away from it maybe doubting every word in there, but then they look up the information to see if I got it right — and see where that leads them. And go on that self-education journey — because it’s the only hope of getting out of the mainstream and making a difference. I mean, to have that sense of purpose — what’s negative about that?

© Susie Day, 2008