Using ropes, some young people descended halfway from railroad bridges to force the train to stop. Others hastily grabbed stones out from under the tracks and in this way prevent their use. Far more, young and old from all over Germany, simply sat down on the tracks until police carried them away. Banners and witty, sarcastic signs were everywhere, also the many-colored tents of those spending two, three, or four days here in this cold, damp, flat stretch of North German landscape. The big yellow X standing here for “NO” was on thousands of caps and coats, it stood out in windows and, over man-size, on crossed poles and beams in surrounding fields. The long railroad trip with 123 tons of radioactive uranium waste in eleven containers could not be stopped on its long journey from northern France, but committed crowds, in well-coordinated actions, forced route changes and 14 hours of delays in both countries. As it slowly neared its destination, an estimated 50,000 protesters (only half that, police officials insisted) spread out around the rail line; at one point 2,000 sat down on 2 kilometers of tracks, while at least 16,000 unfortunate, mostly unhappy cops, also from all over the country, had to put in 12, 16, and 20 hour shifts, costing many million euro. Some tactics were legal, some were not, confrontations remained non-violent for the most part, but one evening tempers ran high and horses, night sticks, water cannon, and pepper spray were sent in. Hundreds were arrested.

All Germany watched in near disbelief as news reports overflowed on the latest actions in opposition to the “Castor transport,” as it was named. When the big tanks with their potentially fatal contents did at last reach the end of the rail line, they had to be reloaded onto trucks for the last twenty kilometers to their final destination, a salt mine deep under the little town of Gorleben. Blocking the way, in addition to protesters sitting and lying on the road or dragging logs or whole trees across it, were over 600 tractors of angry farmers — and even a big flock of goats. The shipment will certainly get to Gorleben, but the government will not soon forget and perhaps never repeat what occurred.

There have been protests here since 1995, sometimes more violent but never so huge. To begin with, the underground storage dump is not safe. It may be gradually heating up, and it is highly probable that contaminated wastewater is seeping out of the mine. It was chosen, many are convinced, because it was in a thinly-populated, out-of-the-way area right across the Elbe from what was once East Germany (the river formed the boundary here). So why should good West German citizens complain? But they did, and they do! The mine was always declared to be a temporary solution, but more and more metal containers with uncertain durability are being piled up while the dangerous radioactivity of their contents will last thousands of years. Thus far, no other site has been proposed.

The reason popular outrage has been so very strong this year is that on October 28th the Merkel government passed a law extending the lives of many atomic power plants from an earlier government’s eight-year limit to a new wobbly limit of 14 years. This extension was so obviously based on a smiley handshake between Merkel and the country’s power utility giants that everyone could see how the two governing parties are endangering the whole country to satisfy the greed of four huge companies. It was simply too clear and too much.

The physical protests up north follow huge autumn demonstrations in Berlin and other cities, with over 100,000 people protesting the extension of atomic production rights instead of investing more in alternate energy. They also follow giant, month-long protests in the usually peaceful, staid city of Stuttgart in the south against the demolition of a popular old central railroad station and a neighboring park with beautiful, ancient chestnut trees — in a dubious deal which would bring billions to favored investors. Somehow, a surprising number of people in Germany are leaving their sofas and demonstrating, angry at being ignored by ruling cliques. As a result, Angela Merkel’s government would find it very difficult to remain in power if elections were to be held today rather than in 2013.

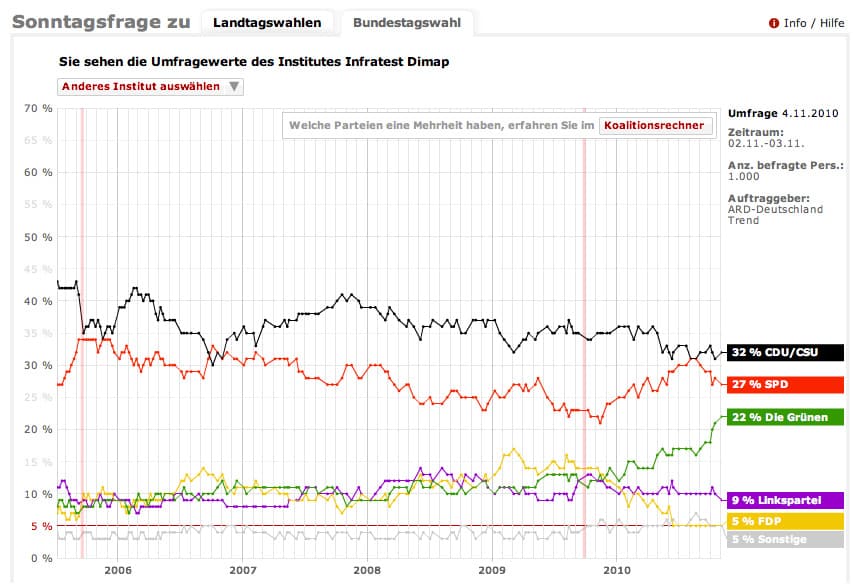

Of the three leading opposition parties, the Social Democrats, though still diminished in poll figures, have gained self-confidence with the knowledge that a coalition with their likely partner, the Greens, could now get a majority. This is because of the swift, almost unprecedented growth of the Greens, who have been very active in both the dramatic Stuttgart events and the anti-atomic movement; their leaders have constantly been in the limelight. In fact, public television channels have been supporting them to an unusual extent, and the weekend bid by a prominent Greens leader, Renate Kuenast, to lead her party in next year’s Berlin elections, with hopes of overtaking the once-so-popular gay Klaus Wowereit, mayor since 2001, was planned so cleverly and treated so favorably that it dominated Berlin’s local news coverage for weeks, until overtaken by the Gorleben events.

And the Left Party? It, too, has taken part in all the protests and demonstrations. Bundestag caucus leader Gregor Gysi himself drove one of the tractors for a while near Gorleben. But its numbers in the West German states were never too large, and more important, the media are united in downplaying it, except for an occasional obligatory sound bite. More importantly, the Left is still caught up in internal disagreement, which seems to have occupied the most attention among top leaders. A congress in Hanover on November 7th tried to patch up disputes and the 600 attending tried to demonstrate a policy of peacefully agreeing to disagree. The center of debate is the draft party program, which is far too militant for the Forum of Democratic Socialism, a caucus inside the party well populated by party officials holding office in the Berlin coalition government and those hoping to win in other East German states, join coalition governments there, and possibly even join a coalition national government with Social Democrats and Greens after the 2013 elections. The Left Party militants, on the other hand, insist that the party reject any and all military expeditions in future, even under the UN; demand that the party refuse any further privatization of public utilities or housing; and warn of basic compromises demanded by the Social Democrats and Greens. The party’s eventual goal must be to overcome rule by huge capitalist monopolies and banks and, eventually, to achieve socialism. They fear that watering down these principles would put the Left on the same downhill ramp which corrupted both the Social Democrats and the Greens, who despite their current militancy have largely become a party of well-off professionals, interested in environment but far less in urgent social issues. The “reformer” group calls such demands unrealistic, Utopian, and harmful to their attempts to gain positions of government power where they can ease the worst economic woes.

The party co-presidents, the popular, calm and collected East Berlin leader Gesine Loetsch and the West German metal union leader Klaus Ernst, said that healthy debate was a good thing and differences would certainly be resolved before the members vote on the new program next year. But regardless of rights or wrongs in the debate, the disagreements have undoubtedly restricted public activities of the party, and this has shown up in diminished poll popularity. Many friends of the Left feel that if the party wants to maintain pressures which proved so significant in recent years it must move beyond internal debates and quarrels and get into action. An amazing sector of the German population now seems more inclined towards militant action than in many, many years.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

| Print