A question that might sound ludicrous to some: what do Trump and liberals have in common? Answer: a penchant for discussing anything other than class and capitalism—seriously.

First, Trump. Having gotten more flak than he bargained for as a result of his racist dog whistles about Charlottesville, Trump-logic dictated a more acceptable proxy. Lo and behold, the call now for patriotism from the National Football League and elsewhere. Who could object to that noble virtue?

But why even play the race and/or patriotic card? The logic of elite rule.

Nothing has proven more effective for ruling class survival since the dawn of class society than all or enough of us agreeing with their claim that the “us” have a common interest. “We’re all in this together,” so goes their time-worn mantra, be it the family, the clan, the tribe, the race, the nation, the company or whatever. That the current occupant of the White House has more capitalist credentials than any of his predecessors and could quickly pirouette from race to an identity that claims that nothing separates him from the rest of us because “we’re Americans” should be instructive—a lesson for those who want to reduce his actions simply to “white supremacy.”

If ever there were a modern U.S. president who needed to pretend to be like the rest of “us Americans” surely it has to be Trump. Indeed, even more so than his darker-skinned predecessor, which is why he worked so hard on his anti-Obama “birther” campaign. Trump played the part of the schoolyard bully to deflect attention from his own atypicality. Never, in other words, has a U.S. president had such a personal as well as class interest in avoiding an honest discussion about capitalism than Donald Trump. How successful he’ll be with his patriotic campaign against the NFL-modern day gladiators and their capitalist masters—the added advantage being that he can imply they’re a different breed of capitalists—and with ebullient cheer leaders like Sean Hannity at Fox in tow, could be telling about the state of politics in the U.S.; a question to which I’ll return at the end.

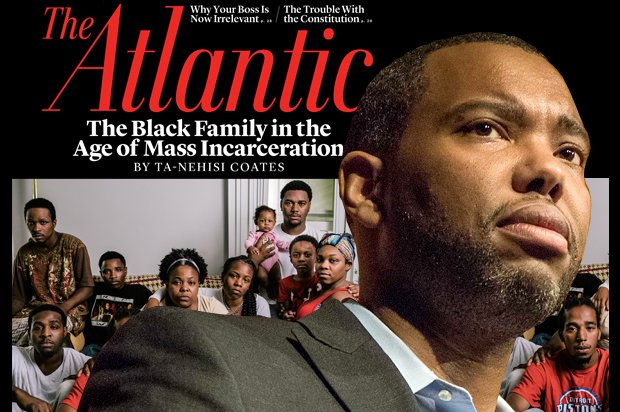

If Trump has a clear class interest in avoiding the class/ capitalism question, what about liberals, as I contend? At present, no one better epitomizes this essential feature of liberal politics than Ta-Nehisi Coates. His recent Atlantic salvo, ever smart and instructive, is a mirror image of Trump’s playing of the race card. “The First White President” argues that “whiteness brought us Donald Trump,” thereby giving Coates and others so inclined the intellectual license to label Trump a “white supremacist.” That the crisis of capitalism, however, was the actual culprit is simply not on his radar. Like Trump, meritocratic liberals such as Coates have a class interest in obscuring their class privileges, as it allows them to evade any critical examination of the system that sustains them. Rather than bite that hand, they blame the victims—“the carnage”—of that very same system.

What Actually Happened on November 8

To try to make his white supremacy/whiteness-brought-us-Trump argument, Coates begins with a tortuous parsing of the election return data. He has no class interest from his privileged perch in beginning with an indisputable fact and about which he’d be on surer ground. Is anyone seriously doubting at this point that if Trump had not received the inordinate amount of “free media” time from the capitalist press—the very same institution that provides for Coates—he would have emerged victorious on November 8, 2016? Obviously, capitalists don’t believe in “free lunches” but the shock and scandal Trump offered on a daily basis ensured there would be nearly uninterrupted coverage of the Trump campaign. Even Trump’s empty podium had more air time than Sanders—and with all the profits to be raked in. Post-campaign Trump bashing has been just as (if not more) lucrative—as the corps at MSNBC can testify. The internal logic of their system, in which everything becomes a commodity to be bought and sold, demands such coverage.

Considering this blind spot, Coates’ reliance on facile generalizations when surveying the election return data should come as no surprise. In his discussion of what happened on November 8, 2016, Coates never even acknowledges that only twenty-five percent of the electorate voted for Trump; or that the largest bloc of eligible voters in the country, about forty-one percent, voted for none of the above: they chose not to vote. In other words, the majority of eligible white voters didn’t vote for Trump; a plurality of them didn’t like their choices.

And about that last fact, there is a deafening silence in Coates’s narrative. The election turned on, as most expert opinion agrees, 206 counties, mainly in the so-called rust-belt. The same counties that voted twice for Obama (in 2008 and 2012), and then flipped to Trump. Can Coates really claim that all of those whites who voted twice for Obama suffered from two bouts of false racial consciousness and finally came to their senses in 2016? Perhaps, as Coates comes close to positing, if you believe that “white supremacy” is written into their DNA— à la Clinton’s “irredeemables.” For those in 2008 who thought that it was impossible for someone with visible roots in Africa to become president of the U.S., despite what opinion polls had said about the prospects for a Colin Powell presidency, Coates’s thesis is likely to be appealing.

A not too-subtle apologist for the Democratic Party, Coates can’t bring himself to admit that the product Democrats were peddling that year was deeply flawed. Why vote a third time for a party that had twice failed those voters and with a candidate so disliked? As of July, according to the most recent polling, Clinton still had higher unfavorables than Trump—and that’s before the recent Donna Brazile revelations about machinations inside the Democratic National Committee on behalf of Clinton during the campaign.. So why were those 206 counties pivotal yet again in 2016? It is because of the fact that we have a truly “rigged system”—or what I call the revenge of the slave owners. The Electoral College is only one of the democratic flaws in the Constitution owing to a concession to slave owners. Their power in shaping that document also explains why the word “democracy” is entirely absent. These well known facts appear to be lost on Coates.

More than anything, it was the end of the “American Dream” that made a Trump presidency possible. In the late 1960’s as the post-World War II economic boom, which had “lifted the boats” of most workers, began to peter out the U.S. economy entered the present period of secular stagnation. The downturn was accompanied by a precipitous drop in trust in government, most notably associated with the carnage in Vietnam and the related Watergate scandal. (The new Ken Burns/Lynne Novick PBS series, its liberal limitations notwithstanding, is especially instructive on this point.) Feeding off of this apathy, it was only a matter of time (longer I admit than many of us anticipated) that U.S. politics would make a decisive turn away from “business as usual.” To paraphrase Malcolm X, Trump is capitalism’s chicken coming home to roost. Coates’s 2015 sabbatical in France evidently failed to teach him that the capitalist crisis is truly systemic and global—plainly evident from the fact insurgents (on the right and left) are disrupting the political establishment of nearly every other advanced capitalist states. It is this “new normal” that explains the rise of Trump, who tread on the very same ground as Marie Le Pen in France. Clearly, “white supremacy” is an entirely inadequate explanation but admitting so would betray Coates’s American parochialism.

If it wasn’t “whiteness,” Coates argues, that explains Trump voters, then why didn’t more blacks and Latinos vote for him? Clearly they too had just cause for being turned off from the business of politics as usual. But Coates certainly knows that Clinton’s failure in the pivotal states is a key reason for Trump’s victory. Enough African American, Latino and youth voters stayed home on November 8 to deny her a victory. They too were part of the plurality that voted for none of the above. Flint, Michigan, is most instructive. The turnout for 2016 was at most half of what it had been for 2012, not surprising given how the political class in Republican and Democratic clothing had abused its residents.

Again, only twenty-five percent of the electorate voted for Trump and of those voters perhaps a quarter had voted twice for Obama. Can Coates, again, confidently call the latter racists? If he is ready to concede that only about twenty percent of the electorate was motivated by “whiteness” in its vote, to be generous, then I have no real quarrel with him. But that’s a very different portrait from the one his article paints—one of “white supremacy triumphant.” And I leave aside the far more important question about voting (opinion polls also): can the registration of a preference for a candidate in a polling booth predict how a voter will actually vote with their feet, on the streets, the barricades: in other words, where real politics takes place? The last time I checked, the voting behavior literature has no answer to that question.

What explains Coates’s thesis when the evidence is so clearly to the contrary? If the Trump election represents, as he claims, a successful backlash to the Second Reconstruction—which he mistakenly equates with the election of Obama, whose victory only registered what that historic breakthrough had already achieved— how does he explain one of the most glaring facts about the U.S. political scene since November 8: the widespread removal of Confederate monuments?

More Confederacy monuments have been sent to the dustbin of history since Trump’s ascendancy than during the tenure of any other White House occupant. Should I repeat that? As renown historian of the First Reconstruction, Eric Foner, explained in the New York Times: “Historical monuments are, among other things, an expression of power—an indication of who has the power to choose how history is remembered in public places.” Why haven’t the original white supremacists like David Duke been able to prevent their removal? Simply because they’ve never recovered from the historical defeat delivered to them by the mainly proletarian movement known today as the Civil Rights Movement—Trump’s election notwithstanding.

After months of organizing on social media, the best that the pro-Confederacy crowd and their allies could bring to Charlottesville was about 500 supporters. The wannabe Nazi-style tiki torch march of about 250 of them on the night of August 11 was dwarfed six nights later when thousands marched by candle light along the same route of at the University of Virginia. A week later in Boston, some 40,000 marched in solidarity! Simply put, Duke and cohorts have not been able to muster enough forces in the streets to protect their sacred icons. Therein is an important measure of the real balance of forces in U.S. politics today.

‘The Crisis of the Black Meritocracy’ (apologies to Harold Cruse)

What explains, then, Coates’s white-supremacy-triumphalist thesis; and, especially, its apparent appeal in mostly liberal quarters?

Those of us who have origins in the historical African American experience and who have found a relatively secure niche in the capitalist meritocratic world like Coates find ourselves in an increasingly anomalous situation. Many of our fellow citizens who look like us, some who we know and might be related to, are not doing as well; some in fact are in deep crisis. How do we explain our relatively good fortune? Are we smarter than the less fortunate? Or, is it simply good luck? If some of us in that world have roots in the house slave reality, as in my case, then we know that luck is the most likely explanation. One way to respond to the discomfort we may feel is to play the race card, to pretend that skin color transcends the increasing class divide amongst African Americans. Skin color loyalty can obscure, like patriotism for Trump, class realities.

We Were Eight Years in Power, the title of Coates’s new book, is telling—the new nostalgic anthem of the black meritocratic tribe. Implied—if not intended—is that African Americans actually had political power during the Obama presidency. And that golden period, not unlike when newly enfranchised former male slaves could vote for the first time during the First Reconstruction, came to an end with the Trump victory on November 8. Coates suggests—again, if not intended—the effective disenfranchisement of those same men beginning around about 1877 with the new Jim Crow regime was comparable to Trump’s election.

But who are the “we”? Clearly not the denizens in black skin who disproportionately populate the skid rows throughout the country, one within walking distance of the residence where the Obama family resided for eight years. Coates’ “we”—Obama’s minions, cheerleaders and wannabees in black skin—are in deep denial about their existence. To suggest that “we were eight years in power” is almost laughable—a cruel joke. It says more about Coates’s class and, hence, political myopia than the reality of the vast majority of all African Americans.

The meritocratic world has its own logic regardless of the skin color and various identities of its privileged occupants. It feeds off the crumbs of capitalist profits. And precisely for that reason it has a material interest in, again, not biting the hand that feeds it. The populist backlash to capitalist business as usual—especially “the swamp,” that Trump demagogically exploits to advance his personal class interests—is, therefore, a threat to meritocratic aspirations. Rather than fault the source of the crisis, the lawful workings of capitalism, meritocrats are prone to blame the victims of that system. The modern-day peasants with pitchforks and their insurgent sans-culottes allies (as was once true for the emergent bourgeoisie) are a threat to their well-being. They engender deep fear amongst the meritocrats.

White trash bashing in one form or another leading up to November 8 by meritocrats of all identities and party affiliation was almost de rigueur. One of the surprises of the election cycle for me as an African American who grew up under Jim Crow was to learn that “white folks” too could be treated with such bitter contempt. In hindsight, the popular TV program of the one-time liberal mayor of Cincinnati, the Jerry Springer Show (circa 1990), should have prepared me for what was so blatantly on display before and since November 8. A distant echo of the contempt that house slaves often had for “poor whites” can sometimes be heard by meritocrats in black skin.

If Coates is arguing that African Americans are still second class citizens when it comes to employment, healthcare, housing, education, and treatment by the so-called criminal justice system (to point out the most obvious arenas), he’s absolutely right. But that’s a different claim from his white-supremacist-triumphant thesis which is dangerous because it blinds working people to the opportunities that have never existed before—a point I’ll revisit shortly—to do away with what he no doubt desires.

To equate, as Coates does, the rejection of a third Obama presidency by a minority of the white eligible electorate—“white supremacy as potent as ever,” in his words—with the overthrow of the First Reconstruction, a defeat that set back the working class in all its skin colors for almost three quarters of a century, betrays a profound lack of historical/political perspective on his part. It is hyperbole at the least.

Exactly fifty years ago, around the same time that Martin Luther King was making speeches about his recent epiphany, Harold Cruse launched his salvo at black leaders in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. The key legislative victories of the Second Reconstruction, he realized—the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the 1965 Voting Rights Act—were insufficient for racial equality. That goal, he repeatedly said in the last months of his life, could only be realized by “a radical redistribution of economic and political power.” Whether King understood the full implications of his aha moment will never be known—let alone his acting on it. Nonetheless, it is hardly a leap to recognize that capitalism is incompatible with racial equality (or any other kind of social equality)—a discussion that upwardly mobile meritocrats steer clear of. Clarity on the cold logic of capitalism is why some of us failed to be seduced into voting for Obama. A rare species of those in black skin in the meritocratic world of the academy, we foresaw (accurately in hindsight) that an Obama presidency would not qualitatively improve the life chances of African Americans given their overwhelmingly proletarian composition. We take no joy in saying, “we told you so.”

Again, ‘what is to be done?’

Only the working class in all its skin colors, genders, nationalities, languages and other identities can bring about a “radical redistribution of economic and political power.” And to consign capitalism to the dustbin of history would require, for the unique setting of the U.S., a movement that must certainly grapple with—but refuses to be confined to—the racial categorical imperatives that define Coates’s myopia.

Owing to the profound changes that the Second Reconstruction brought about, progressive forces are in a stronger position today than they’ve ever been to realize such a goal. The multi-racial, multi-gendered, and multi-national character of the Black Lives Matter actions that began with the Trayvon Martin case in 2012 stand in vivid contrast to the almost exclusively African American urban rebellions against police brutality that commenced in 1964. So too do the composition of the counter actions that dwarfed the pro-Confederacy mobilizations from Charlottesville to Boston. Both sets of actions, along with other changes too long to list, testify to strengths of the present position that were absent fifty years ago. They all constitute the necessary, if not sufficient ingredients, for a “radical redistribution of economic and political power.”

Which, again, highlights what is so problematic about a Coatesian perspective. His description of what took place on November 8 is one that indicts most, if not all, “white people.” By implication, white Trump voters are for Coates, as they were for Clinton, “irredeemable”—they are to be written off. But why are workers in white skin who voted for Trump—again, for the umpteenth time, only a minority of them—any more politically deluded (hence worthy of dismissal) than those in black skin who voted for Clinton? Coates is smart enough not even to attempt a positive case for Clinton. Only by implication can he indict and discount those who didn’t vote for the Democratic Party candidate. In so doing he rules out a critical ingredient needed for the coalition to realize King’s post-March on Washington dream, white workers—no, they’re not about to go away however much liberals might so wish—and why what he argues for is dangerous. And that they are likely to be better armed than the world that Coates comfortably lives in today should be of some interest to anyone who too desires a “radical redistribution of economic and political power.”

Most telling about Coates’s “First White President” article is the way it ends: with not even a hint of a way forward. That lacuna betrays the luxury of those who, again, have found a privileged niche in the capitalist order and can afford to critique without offering an alternative. The real test of any apparently smart critique is whether it offers a solution.

Coates recently responded to a critic of his “First White President” essay who also questioned his “white-supremacy-as-US-essence” thesis by saying that he has no interest in seeking “common ground with white supremacists” (see this interview Coates on C-SPAN). By that he meant, apparently, anyone who voted for Trump. But to assume that what a person does in a polling booth, what they might say to an opinion pollster or on social media is the end all and be all of politics is to be afflicted with what I call voting fetishism. Decisive in politics is how, once again, someone votes with their feet in the streets, on the barricades and on the battlefields.

Would Coates really not seek “common ground” with one of the accusers of sexual harassment by Alabama Judge Roy Moore because she voted for Trump?

Thank God for all of those who at one time or another have patiently and civilly challenged the half-baked ideas that I might have expressed in the class room, registered in a polling booth or told to a pollster (I’m still the Luddite who doesn’t’ do social media). Coates, I think, would agree. So the question really is with whom of those who hold racist, sexist, homophobic, chauvinist ideas—just to list the most obvious and consequential—should we spend time in challenging, with the intent ultimately of winning them to the side of the toilers? Paying attention to what a given layer of society has the most to gain (or lose) from a “radical redistribution of economic and political power” is, I contend, the criteria to be employed. An aspiring or even successful meritocrat in this historical moment—with a stagnant or even shrinking “economic pie”—is, unless the evidence says otherwise, an unlikely prospect. They’re likely to be fearful of redistribution. But even if they’re not, they’re probably pessimistic about its chances. Nothing better defines the meritocratic ethos than its lack of confidence in the fighting capacity of the toilers and belief in the invincibility of the ruling class. Hence their incessant need to be part of “the winners.”

In this unprecedented era of the disappearing “American Dream,” I believe it is worth the effort to challenge the backward ideas that workers—whatever their skin color, gender or nationality—may be spouting at any given moment (including a fetish of voting for Democrats). They, unlike meritocrats, “have nothing to lose but their chains.”

The only effective counter to Trump’s new-found patriotic campaign is to reject its assumption of a “we,” an “us,” or, an “our”—another one of the half-baked ideas that workers often spout. It requires the kind of consciousness Malcolm X displayed when he told an audience of African youth in 1964, “No, I’m not an American; I’m one of 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism.”

When Coates, toward the end of his “First White President” article, writes about the “American tragedy now being wrought,” i.e., the Trump presidency, he reveals a degree of ownership about “America” that is foreign to us of his father’s generation. It registers how much the Second Reconstruction has “wrought.” But his upward mobility from black working class origins to meritocratic status comes with a price owing to it being unaccompanied by a mass movement that an earlier generation of similar black youth had for mooring. To have come of age politically in the world of Fidel and Malcolm as some of us did is indeed good luck.

Coates fashions himself as, or aspires to be, today’s James Baldwin. But without Malcolm X and what he represented—the insurgent Black masses—Baldwin would have lacked the human material about which he could be so trenchant an observer. And it’s the Malcolms, those who are willing to put in the time and effort to motivate, organize and mobilize the toilers in all their identities, who are decisive in history—and not the observers however astute they may be.

The response of revolutionary socialists to the ruling class campaign to recruit workers to the Second World War is still the best answer to the siren call of patriotism. Rather than being silenced by the invocation of “America,” they countered that there isn’t one “America.” There are in fact two—the “America” of the ruling class and the “America” of the working class: with all of the political consequences so implied. The Burns/Novick PBS series on the Vietnam War—despite, again, liberal framing—should be required viewing for those who don’t understand why making and acting on the distinction can be a matter of life or death.

As long as racial identity is prioritized over class identity and the logic of capitalism, what Coates’s white-supremacy-as-the-essence-of-US-politics thesis does, is to operate on the same playing field that Trump learned long before Barack Obama to skillfully navigate and manipulate to his advantage—and with all of the potentially deadly outcomes.

Is the proverbial glass half empty when it comes to racial equality in the U.S.? Of course; it can’t be otherwise under capitalism. But is that the end of the story as Coates would suggest, in almost Greek-like tragedy? To believe so is to fail to see the glass half full side of the story. That would be the real tragedy.