Seven years of military dictatorship in Argentina ended in 1983, but the regime’s officers remained a powerful force. The newly formed democratic government tried to appease them by passing two laws that granted almost total impunity for the junta’s many crimes: the “disappearance” of as many as 30,000 people, systematic torture, the dumping of live detainees from airplanes, and the practice of seizing the children of murdered activists and handing them over to childless military couples.

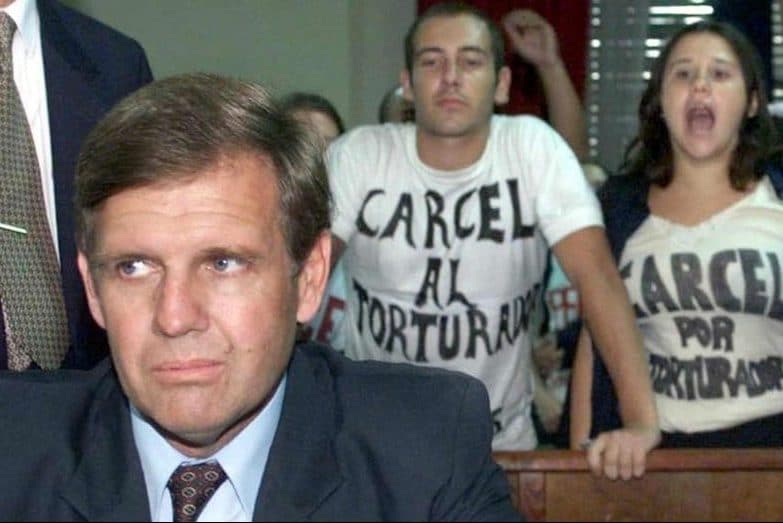

In the mid-1990s many of the survivors began fighting back against the impunity. Torture victims, parents of the disappeared, and many of the adopted children, now grown, started organizing public events intended to shame and humiliate the oppressors. Known as “escraches” from an Argentine colloquialism, these generally nonviolent protests ranged from large demonstrations at the homes of regime officials to a spontaneous action that kept a notorious torturer from enjoying a ski trip.

The people participating in escraches were doing more than just venting their anger and making life unpleasant for the criminals. The protests kept the dictatorship’s “dirty war” in the public eye; they prevented politicians and the media from letting history pass from memory and provided a warning to the people who might try to repeat that history. And the escraches almost certainly made a difference. Some prosecutors and judges eventually defied the two impunity laws by bringing criminal cases against the junta’s members and enablers. In 2005 the Argentine Supreme Court overturned the laws, and at least a few aging officers finally faced justice.

Our government hasn’t carried out “dirty wars” against its own citizens—not recently, in any case—but impunity is as pervasive here as it was in Argentina thirty years ago. Over the past half-century U.S. officials have abetted or directly ordered the killings of millions, in Vietnam, Indonesia, East Timor, Central America, the Middle East, and none of the main perpetrators have ever been penalized. Henry Kissinger is one example among many: his crimes included providing encouragement for the murderers, torturers and kidnappers in Argentina. Now 95 years old, Kissinger is not only free; he gets cited as an adviser by Democratic politicians, and self-proclaimed human rights activists socialize with him.

Recently, a number of U.S. citizens and residents have responded to the Trump administration’s family separation policy by publicly shaming various officials, upsetting their dinner plans and even protesting outside their townhouses. This has inspired a great deal of hand-wringing from the U.S. media. People are being punished for their “political views,” journalists tell us; we need to think twice before “justifiying incivility”; and refusing to feed rich white officials may be the same as discriminating against African Americans or LGBTQ people.

The U.S. media outlets are just playing their customary role in maintaining impunity, as they have over the years with Kissinger and company. We need to remember that these protests aren’t about political views: they’re about government officials violating international law, U.S. treaty obligations, and basic human rights. And they’re a reminder that in a properly functioning democracy, Trump and his collaborators would already have been removed from office and criminally charged for their actions.

It’s hard to say now what direction the protests will take, but they could turn out to be the U.S. version of Argentina’s escraches. Someday members of our political elite may finally have to answer for their crimes in front of a judge and a jury.