The extended heat wave afflicting India has surpassed 50⁰C (122 degrees Fahrenheit), even worse than the terrible scorcher that was assessed “the 5th deadliest on record” and claimed thousands of lives in 2015.1 Matters could get even worse, the city of Chennai has almost run out of water, putting 10 million lives at risk.2 South-eastern Africa has been hit by an unprecedented series of devastating cyclones, affecting millions of people.3 The global North is beginning to feel the crisis too. Forest fires are increasing across North America and Australia. The late June heat wave across continental Europe pushed temperatures in France over 45⁰C, and triggered a wildfire in Catalonia, which authorities believe started when a pile of manure self-ignited.4 The **** really has hit the fan.

“Widespread social collapse is now inevitable” in the near term is the conclusion of an influential paper Deep Adaption that draws together the evidence that “it is too late to avert an environmental catastrophe.” Author Jem Bendell identifies Arctic ice melting and a host of other impending “non-linear changes in our environment” that are about to “trigger uncontrollable impacts on human habitat and agriculture, with subsequent complex impacts on social, economic and political systems.” 5 We should be clear that environmental catastrophe is already upon the Global South. Any delays to overcoming the causes will not only affect future generations, true though that is, but billions of human and other lives today. Bendell shows the environment catastrophe is also social collapse, which prompts the observation that to solve this we need to connect critical social science with the body of environmental science. Is adaption, however deep, the right paradigm in which to pose the problem?

There is no global social unity in the face of climate disaster. On the contrary, Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights emphasises that global division is the fundamental challenge. “Perversely, while people in poverty are responsible for just a fraction of global emissions, they will bear the brunt of climate change, and have the least capacity to protect themselves…. We risk a ‘climate apartheid’ scenario where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger, and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer.” His report calls for complete social and economic transformation: “addressing climate change will require a fundamental shift in the global economy, decoupling improvements in economic well-being from fossil fuel emissions.”6

Fundamental shift? Complete social and economic transformation? System change not climate change is truly on the agenda.

Identifying the Obstacles to System Change in Britain

In Britain the chief generators of climate apartheid can be summed up in two words, “BP” and “Shell.” Hydrocarbon capital is especially concentrated in the UK: Shell acquired British Gas in 2015, and with BP it dominates the sector. These two huge oil multinationals are respectively fourth and sixth on the all time list of the world’s most egregious carbon emitting entities.7

“BP and Culture: Time to break it off.” Credit: Art Not Oil coalition.

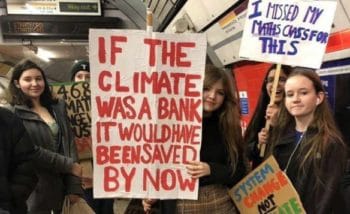

Two recent articles highlight just how important BP and Shell are. On 21 June actor playwright Mark Rylance resigned from the Royal Shakespeare Company over its BP sponsorship deal.8 Days later environmental author George Monbiot called for the destruction of the “planetary death machine” that is Shell.9 Both writers have the grace to acknowledge their debt to grass roots activists. Rylance praises the BP or not BP? campaign that has used imaginative tactics to oppose the corporation’s sponsorship deals with iconic cultural institutions.10 The wonderful school strike rebellion clearly effected Monbiot, who has shifted his position from criticising “capitalism with adjectives” (so leaving the door open to another, greener type of capitalism) to the fuller recognition that capitalism as such is the fundamental systemic problem that is driving global warming.11

These welcome interventions come at a time of polarisation, fed on the right by resurgent government propaganda in praise of a post-Brexit “Global Britain”, openly seeking to reinvent the zeitgeist of imperialism.12

This article brings together these two themes: we look directly at the role of UK based fossil fuel corporations in creating climate disaster, and analyse how this situates what “Global Britain” really means. We urge a shift in the debate from its current nationalist framing. For example, The Observer’s science editor Robin McKie assesses the viability of Extinction Rebellion’s demand for comprehensive action to save the planet by 2025: “The crucial question is: when? Just how quickly can we eliminate our carbon emissions?”13 The purpose of this article to ask not just when, but where? Where are “our” carbon emissions? Does a zero emissions UK just mean zero emissions in the UK, or zero emissions for which the UK is responsible? We will find that the there is an order of magnitude of difference between the two. This leads into a discussion of the limitations of lobbying as a movement strategy, and we propose a more direct approach to stopping the “planetary death machines.”

Fossil Fuels and the imperial structure of British capitalism

The seven biggest market listed oil companies in the world—based on their capitalisation—are Exxon, Shell, Chevron, PetroChina, BP, Total and Sinopec: two each from the US, UK, China and one from France.14 Shell and BP are considered two of the West’s five oil super-majors, they exemplify the markedly imperial structure of British capitalism, which is clustered around finance, the extractive conglomerates and a clutch of consumer multinationals.

London is a safe haven for carbon generating corporations, it provides developed capital markets, friendly governments, and hardly any opposition to their social licence to operate, until recently. Closely related to the UK’s platform for Big Oil are its close ties with Big Mining. Four of the world’s top six mining giants—BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto Zinc, Glencore and Anglo American—are listed in the FTSE top 20 companies on the London stock exchange.15 Another aspect is that (Royal Dutch) Shell, BHP, Glencore and Anglo are in different ways bi-national rather than exclusively UK companies, testimony to the enduring significance of colonial empire in contemporary connections.

Companies most involved in generating green house gases, those in the Oil and Gas and Basic Materials sectors, together constitute 24.9% of the market capitalisation of the FTSE top 100 companies. The more discrete hub of the whole business, finance, constitutes 23.7% of market capitalisation.16 These three sectors constitute half of British big capital, their interests and modes of accumulation are at the cornerstone of the ruling class.

The FTSE’s top 100 companies draw over 70% of their revenue from abroad, emphasising that, quantitatively at least, in global Britain profits from overseas are more than twice as important as the exploitation of workers at home.17 Revenue from overseas is even more accentuated in the Basic Materials (98%) and Oil and Gas (93%) sectors, adding the dimension of global environmental exploitation to international labour exploitation.18 Both Shell and BP operate in more than 70 countries around the world. Shell’s global production “averaged 3.7 million barrels of oil equivalent a day in 2018.”19 Still carrying liabilities for its polluting Gulf of Mexico disaster, BP is not as highly valued by the stock market as Shell, which it nonetheless matches it in terms of actual hydrocarbon production. Moreover BP is ramping up its portfolio. The company started six major projects in 2018, which will add another 0.9 million barrels to its existing daily production of 3.7 million barrels oil equivalent.20 It plans another five more projects in 2019.21 In their specifics, and in their contribution to total emissions, these projects are worsening environmental harm.

The reason that Shell and BP stick with fossil fuels and are indeed expanding their carbon production is evident enough: it is hugely profitable. Crude oil prices have recovered from their fall in 2014. Shell’s profits have increased year on year since 2015, reaching $26.4 bn in 2018. Return on capital employed (ROCE) is a key performance indicator for capital markets and a close equivalent to Marx’s idea of the rate of profit22. Shell’s capital employed in 2018 was $281.4 bn, rendering a profit rate of 9.4% ROCE.23 BP reports its 2018 underlying profit at $14.5 bn, less than Shell’s, but against the lesser $129.6 bn capital employed, BP made an even higher profit rate of 11.2% ROCE.24 These profit rates, and the total return to shareholders, are what matters as far as the capital markets are concerned.

The financial numbers indicate how much wealth is sucked out of the rest of the world and is converted into ‘income’ for shareholders, banks and the UK treasury. Following the money, we see that Shell’s investors received $15.7 billion in dividends. Its biggest shareholders are Euroclear Nederland, owning 22.0%, and London based Guaranty (Nominees) Limited, with 18.5%; both are investment vehicles whose client beneficiaries, the ‘nominees’, are not disclosed. Six US investment banks hold a further 25.2% of Shell’s shares, also on behalf of undisclosed beneficiaries.25 Although BP has a wide shareholder base of both institutional and individual investors in the UK, its biggest reported shareholdings are from three US finance houses JP Morgan Chase Bank, with 27.3% ; Black Rock, 6.6% and The Vanguard Group, 3.5%.26

Taken together with the ownership patterns of the big mining companies, these figures indicate a broad pattern of money from global extraction operations being sucked into London as the executive and financial centre; and then distributed as property income through asset management houses to shareholders in the UK, and to similar rentiers in the US, Western Europe and some, mostly white, ‘Commonwealth’ countries.27

Corporate UK’s Real Responsibility for GHG Emissions

What does this economic structure of continuing imperialism have to do with the UK’s responsibility for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? An awful lot, it turns out.

According to BP’s World Energy Review, the UK consumes 1.4% of the world’s primary energy.28 Another source estimates the UK’s carbon emissions in 2017 as 385 Mega tonnes of carbon dioxide CO2, that is under 1.1% of the world total that is 36,153 MtCO2.29 By either method, the UK contributes a little over 1% of the world total. Note here two qualifying points, these are measures of present emissions produced physically in the UK.

Being clear about the data is hugely significant. For example, Ed Miliband is a respected voice in the climate debate, because as Energy Minister he navigated the Climate Change Act in 2008 through Parliament to implement Kyoto targets to reduce six greenhouse gases in the UK by 80% by 2050.30 Citing the above figures, Miliband now claims the UK is on a progressive track of emission reduction,

our recent record looks good by international standards: renewables have grown to provide 33 per cent of our electricity and our power systems have just had their first coal-free fortnight since the industrial revolution. Indeed, total emissions have now fallen to the levels of the 1880s—and no, that isn’t a typo.31

No, not a typo, it’s a lie. Not the ‘literal denial’ that is outright lie of climate change deniers, but a lie nonetheless, a form of completely misleading ‘interpretive denial’ shared by the climate change deflectors leading the mainstream debate.32 The reason is obvious indeed, it all depends in what you define as ‘total’. There are three areas that have to be added on to Miliband’s ‘total’ to get a more realistic estimate, with the result that the GHG emissions for which the UK is really responsible are both several times greater and still increasing. The areas are international transport, the surplus of imports over exports, and foreign investment. We will take them in turn.

Greta Thunberg rightly points out that the first two responsibilities are omitted in the UK’s “very creative carbon accounting”, which “does not include emissions from aviation, shipping and those associated with imports and exports.”33 Her academic brief argues that a further 8% emissions should be added to account for aviation and shipping.34

Addressing the bigger imports issue, a study by Nina Morgan differentiates territorial GHG emissions from emissions that arise in the production of goods that are then imported into the UK. Morgan found that since 2004 “the GHG emissions embedded in products imported into the UK have been higher than those resulting from domestic production.”35 It estimates that by 2008 the UK’s emissions comprised households 150 Mt CO2 equivalent, domestic production 390 MtCO2e, emissions embedded in imports 470 MtCO2e, adding up to 1,010 MtCO2e. Offshore carbon emissions are still deepening the UK’s ecological debt. One example, in 2017 the UK imported around $16.5 bn worth of forestry products, a major stimulus to deforestation and so a double contribution to climate change.36 Using these additional estimates to take international trade into account brings the combined UK production and consumption embedded emissions to around two and a half times more than Miliband’s ‘total’.

The UK’s overall responsibility for inducing climate change is however yet greater again, once we take account of the third additional area, which is foreign investment of UK companies overseas and the full extent of the GHG emissions that they profit from.

The original survey on this by Richard Heede identified 90 ‘carbon majors’ responsible for 63% of cumulative worldwide emissions and 77% of current emissions in 2010. He found state owned corporations in Saudi Arabia, Russia and China have since the 1990s been the biggest emitters. US and UK investor owned companies are more significant historically and remain prominent in the ‘investor owned’ part of the sector.37 The following table presents a summary of Heede’s findings, insofar as they related to UK based fossil fuel corporations.

Table 1: UK Corporations in Global Top 90 Carbon Majors 2010

| Source Entity | 2010 Emissions, MtCO2e | Proportion of 2010 world total % | Cumulative 1854-2010 Emissions, MtCO2e | Proportion of cumulative world total % |

| BP | 554 | 1.54 | 35,837 | 2.47 |

| Shell | 478 | 1.33 | 30,751 | 2.12 |

| BHP | 320 | 0.89 | 7,606 | 0.52 |

| Anglo American | 242 | 0.67 | 7,242 | 0.50 |

| Rio Tinto | 161 | 0.45 | 5,960 | 0.41 |

| BG Group | 97 | 0.27 | 1,543 | 0.11 |

| UK Coal | 19 | 0.05 | 794 | 0.05 |

| UK based corporate | 1,852 | 5.19 | 81,436 | 7.51 |

| Total global emissions | 36,026 | 100.00 | 1,450,332 | 100.00 |

These fossil fuel emissions are far greater than either the usually cited ‘total’ of 385 MtCO2e, and even our expanded estimate of around 1,000 MtCO2e taking trade into account. Combining all the three additional areas of emissions gives a total of 2,862 MtCO2e. None of this is an exact science, but on the best available estimates it is clear that bringing in the overseas emissions due to trade and foreign investment into the picture indicates that the UK’s real responsibility is around 8% of current total global emissions, that is more than seven times greater than emissions in the UK alone.

Heede’s results were fed into the Carbon Majors Database which has been updated by the CDP project. The latest data for 2015 shows that “of the 635 GtCO2e of operational and product GHG emissions from the 100 active fossil fuel producers, 32% is public investor-owned, 9% is private investor-owned, and 59% is state-owned.”38 The category ‘public investor-owned’ means private companies with shares traded on the stock market. CDP’s report is aimed primarily at these investors, on the assumption of goodwill on their part. Its data reveals a picture that is still largely unknown by the public at large, including even activists concerned to halt climate change.

Table 2: UK Corporations in Global Top 100 Carbon Majors 1988-2015

| Producer | Cumulative 1988-2015

Scope 125 GHG, MtCO2e |

Cumulative 1988-2015

Scope 326 GHG, MtCO2e |

Cumulative 1988-2015

Scope 1+3 GHG, MtCO2e |

Cumulative 1988-2015

Scope 1+3 of global industrial GHG, % |

Average annual 1988-2015

Scope 1+3 GHG, MtCO2e |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 1,212 | 13,805 | 15,017 | 1.7 | 536 |

| BP | 1,072 | 12,719 | 13,791 | 1.5 | 493 |

| BHP Billiton | 588 | 7,595 | 8,183 | 0.9 | 292 |

| Rio Tinto | 297 | 6,445 | 6,743 | 0.7 | 241 |

| Subtotal: UK based top 4 | 3,169 | 40,564 | 43,734 | 5.0 | 1,562 |

| Total sample (100 producers) | 58,328 | 576,506 | 634,835 | 70.6 | 22,673 |

The oil giants Shell and BP are each responsible for more worldwide emissions than all the emissions produced inside the UK. The global warming effects of mining giants BHP Billiton and Anglo American contribute about three quarters and two thirds of UK domestic emissions.Just these four companies are together responsible for four times more carbon emissions than every production and consumption activity inside the UK.

Part of the reason that this is not more widely known is of course under the label of supposed transparency the corporations try to keep the real extent of their responsibility out of the discussion. The CDP study differentiates between ‘Scope 1’emissions incurred in the direct operations of extraction (e.g. ‘self-consumption of fuel, flaring, and venting or fugitive releases of methane’. and ‘Scope 3’ emissions from the combustion of the sold oil, gas, and coal products. It can be seen from Table 2 that Scope 3 emissions are far more significant, they are ten times greater than Scope 1 emissions.39

Corporate deception has to be overcome before we arrive at the fuller estimates. BP has pledged a corporate strategy to meet the Paris goal, which it claims is ‘Good news for both investors and the planet’.40 Let us see. BP now reports progress against climate change targets, which apparently shows an improving picture, precisely because it only discloses its direct operational Scope 1 emissions, which it reports reduced from 51.2 MtCO2e in 2015 to 48.8 MtCO₂e in 2018, down by just 2.4MtCO₂e, but at least heading in the right direction.41 However, as we saw above, BP is expanding its oil and gas extraction by 24% from 3.7 million to 4.6 million barrels of oil equivalent daily. This will actually increase the annual downstream and final use GHG emissions of its products by around 118MtCO₂e, some fifty times more than the heralded operational reduction.

BP’s immediate production expansion target of 0.9 million boe/d is just its major projects in the three years up to 2021. An NGO consortium report estimates the expansion of the biggest fossil fuel companies over fifteen years from 2016 to 2030, based on projects reaching Final Investment Decision (FID) in the period. On the criterion of GHG emissions from these new extraction projects, it is estimated that Shell will produce another 9,836MtCO2 ranking it the third biggest globally (after Russia’s Gazprom and the National Iranian Oil Company). BP will produce 5,965MtCO2, ranking it eighth (after Exxon, Chevron, Saudi Aramco and Qatar Petroleum).42 Simple arithmetic gives us an average annual new project expansion of GHG emissions from Shell and BP of about 1,000 MtCO2, that is around three times total emissions in the UK.

How to interpret these findings from the data? They should completely change the orientation of the debate. They show that we cannot address the problem from the perspective of narrow energy nationalism. The data cited by Miliband and others in the official UK climate debate is not just a bit in error, it is entirely misleading as to the scale of the problem and wholly misdirecting as to what must be tackled to address the problem. Corporate UK draws massive profits from largely unnoticed, wholesale, overseas emissions. The contemporary phase of historical ecological imperialism that this data further evidences puts any claims of UK leadership in tackling carbon emissions in a totally different light.43

Financial Connections: Scenario Planning and ‘Banking on Climate Change’

Next we consider the connections with finance. Joint stock companies can raise capital either through bank loans (debt) or issuing shares (equity). The finance sector is involved in climate change through both these standard channels, as well as insurance and a myriad of other ways.44

Global bank lending to fossil fuel companies from 2016 to 2018, since the Paris Agreement was adopted, was $1,919.7 billion ($1.9 trillion). These loans facilitate expansion into the Arctic, fracking, deepwater extraction, tar sands exploitation, coal mining and so on. The US leads this particular race to destruction, six US banks lent $709.6 billion. JPMorgan Chase, the biggest single financier of fossil fuels, lent $195.6 billion. Five Canadian banks came next lending $338.2 bn. They were followed by Japanese, Chinese and then UK banks as the biggest lenders (see Table 3).

Table 3: Fossil Fuel Finance from 2016-2018

| Country of HQ/Bank | 3 years of Fossil Fuel Finance (2016-2018), billions of USD | |

| Bank | Country Sub-total | |

| USA 6 top banks | 709,630 | |

| Canada 4 top banks | 338,208 | |

| Japan 3 top banks | 185,847 | |

| China 4 top banks | 168,115 | |

| Barclays | 85,179 | |

| HSBC | 57,808 | |

| Standard Chartered | 15,244 | |

| Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) | 4,368 | |

| UK 4 top banks | 162,599 | |

| France 4 top banks | 140,435 | |

| Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain 5 top banks | 123,608 | |

| Switzerland 2 top banks | 83,263 | |

| Grand Total | 1,911,705 | |

Barclays Bank and HSBC are picked out as the ‘Worst in Europe’ for banking fossil fuels and for financing fossil fuel expansion. Barclays is rated “Top European banker of fracking and coal power.”45

The City of London is not only a hub for financing fossil fuels, it also hosts Lloyds, one of the biggest insurance and reinsurance markets in the world. The insurers are increasingly concerned with the growing demands for compensation due to extreme weather events. There are counteracting tendencies in play. On the one hand Lloyds’ brokers compete with other international insurance hubs as to how “climate wise” their services are, on the other hand claims from major losses were above average in 2017, and could rise even more. To stay in profit the insurers have to get their research, premium pricing and especially their risk management right.46

The potential for climate change converting through the various capital markets into rapid destabilisation of the entire financial system has not escaped the regulators. The Bank of England was among the small group of central banks that formed themselves into the Network for Greening the Financial System in 2015 to ensure that international finance becomes resilient to climate risks.47 In a linked initiative, the international Financial Stability Board of the Bank for International Settlements set up the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) to address financial risks due to climate change. The TCFD recommends that there should be full reporting by companies of their environmental risks as part of their duty of financial disclosures to “investors, lenders, insurers, and other stakeholders.”48 The primary transparency is to investors, the role of the wider public subsumed under ‘stakeholders’ is entirely marginal to these initiatives that are essentially to protect financial assets and the stability of the capitalist system.

The TCFD initiative is full-on mainstreaming of climate change concerns. It is avowedly private sector led, a collaboration between the select top banks, corporations and asset investors. These principal actors in capital markets seek to place climate change within their standard risk management framework. They have come to together to scenario plan their way towards stabilising and protecting capital assets through the climate crisis. Their purpose is not to stop climate change but to discount any asset risks associated with it.49 The idea is that disclosure will encourage investors to “channel investment to sustainable and resilient solutions, opportunities, and business models.” More transparency is required “to spur action on climate change through market forces” writes TCFD chair, New York multi-billionaire Michael Bloomberg.50

Disclosure is itself now seen as giving competitive advantage for corporations seeking investment, and many big companies are moving in this direction. The CDP Carbon Emissions project was set up to provide a database that “tracks the progress of corporate action on climate change.” The group’s UK report carries the strap line “Written on behalf of 803 investors with US$100 trillion in assets.” Again, the purpose is to provide “data across capital markets to inform better decisions and drive action.”51 The idea is that the Paris Agreement can be implemented by companies voluntarily taking steps towards lower carbon emissions. Of the 1,073 global companies responding, 256 are in the UK. However, by almost every target set, UK companies are rated worse than the global sample in the database.52

If UK companies want to attract global investors, they will have to up their game in monitoring and reporting climate risk. This issue is crucial when we come to Labour Party’s new ‘radical’ climate change policy, which is little more than a nudge to move capital markets in the direction they are already heading (see below).

Climate Hypocrisy and UK Political Corruption: Don’t Mention the Multinationals

BP and Shell are heavily involved in the ‘revolving door’, exchanges of top personnel with government and the highest echelons of the civil service. But pace authors who frame this phenomenon as the special child of Thatcher and neo-liberalism,53 the corruption of the UK state to imperial ends is centuries old and so normalised as to question the notion of corruption as a simple exchange. Neo-liberalism did add a new chapter, as the latest addition to the multiple forms of corruption at home and abroad that are intrinsic to the essence of ‘Global Britain’. Imperial corruption, like its partner militarism, is completely organic to British institutions. That is, the British state is not so much recently captured by the multinationals as repeatedly capturing on their behalf. The corruption of all the main political parties means they deflect attention away from the dirty business of imperial capture and extractivism.

The ruling class strategy to co-opt and tame the Green Revolution into harmless parliamentary channels is well underway. On 27 June an amendment to the Climate Change Act came into force, increasing the target from 80% to 100% fulfillment by 2050.54 Miliband’s self-congratulatory claim fits in with the establishment narrative that the UK, the first industrial polluter, now has a pioneering green message to tell the rest of the world. There is no end to the gall of the British ruling class, which now preens itself on being the first G7 country to commit to zero net carbon emissions. Based on narrow energy nationalism, we have seen that it is based on a downright falsehood, but one that has become the common official mantra.

Only by keeping the UK’s continuing destruction overseas under wraps could these claims be even entertained. Yet even in respect of the UK they are complete hypocrisy. The real government and corporate extractivist agenda ploughing ahead is revealed in the report Sea Change, which shows that government policy is to maximise UK shelf oil and gas production, projected to continue for at least another 25 years. The foreseeable consequence will obliterate the government’s own climate change commitments: “the UK’s 5.7 billion barrels of oil and gas in already-operating oil and gas fields will exceed the UK’s share in relation to Paris climate goals—whereas industry and government aim to extract 20 billion barrels.”55

Sea Change highlights the UK government’s ‘generous tax giveaways’ to big oil corporations, to such a degree that in 2015-2017 the Treasury paid the companies more than it took from them. The biggest beneficiaries were BP, Canadian Natural, Exxon and eight others. The purpose of the tax breaks is to encourage further investment in North Sea oil and gas production. The cumulative effect of the current subsidies on carbon emissions is to boost GHG by over 1,000 MtCO2, with further subsidies more than doubling that. The authors conclude that “oil and gas extraction will add twice as much carbon to the atmosphere as the phase-out of coal power saves.”56

The report’s third key finding requires the triumph of hope over experience, it urges a radical change in policy direction, to scale down hydrocarbon extraction and refocus efforts on a green economy. “Given the right policies, job creation in clean energy industries will exceed affected oil and gas jobs more than threefold”, backed up with a set of recommendations of how to go about it.57

The unavoidable question here is to do with political agency, that all important ‘given’ that is hoped for but is not in fact a given at all: what is the real possibility of any immediately foreseeable UK (or Scottish) government adopting radical, structurally changing, green policies? Will the protests so far be enough? What is the nature of the political sea change required?

Beyond Politics, Old Politics or a New Politics?

Extinction Rebellion (XR) has achieved a critical mass beyond that of any other direct action campaign (for adults). Mass arrests at road blockages were followed up with a ten day takeover of central London, under the banner of ‘Beyond Politics’.58 XR co-founder and strategist Roger Hallam has revisited the civil resistance tradition and advocates mass radical non violent action. He writes “The rich and powerful are making too much money from our present suicidal course. You cannot overcome such entrenched power by persuasion and information. You can only do it by disruption.”59

The disruption worked, the fire alarm has surely gone off—but what now in terms of system change? Notably, XR is broad enough to contain different trends. Hallam states that he won’t take the fight to the multinationals “arguably yes, but probably not”, whereas many in the grass roots see capitalism as the central problem. Some XR activists targeted Shell as a climate change denier, but the movement is yet to take the programmatic step with Monbiot of calling for the company’s destruction.60

Levering the direct action, XR’s follow up strategy is imaginative, radical forms of lobbying, “to force the government into sanity.”61 This clearly cannot get much traction with the reactionary and mendacious Conservative Party, let alone work in the midst of Brexit chaos. Hallam’s strategy would effectively take XR into a tacit alliance with Jeremy Corbyn’s newish Labour Party. As backbenchers both Corbyn and John McDonnell had honourable records of support for just causes, two amongst just a handful of genuinely progressive MPs. But things have changed, the corrupting logic of power has taken over. Here is the rub, even under Corbyn, probably its most progressive leader ever, the Labour Party has not broken from its long tradition of backing British multinationals. Read the Party’s one day climate emergency debate and you will find that not one of the scores of MPs who spoke even mentioned the fossil fuel corporations that, as we have seen, stand out as the chief generators of emissions.62 Without this, Labour’s Green Industrial Revolution amounts to a green glossed version of ‘British jobs for British workers’, while the planet fries thanks to Shell, BP and the big mining companies.

“Our Mother Earth—militarized, fenced-in, poisoned, a place where basic rights are systematically violated—demandsthat we take action.” Berta Cáceres, assassinated in Honduras, remembered in XR protest, Oxford Circus, London April 19, 2019. Photo Credit: “Berta Cáceres a powerful symbol of resistance at Extinction Rebellion protest,” rabble.ca.

As shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, McDonnell has laid out his party’s plans, calling for unity “to overcome the existential threat of this climate emergency.” The speech was billed ‘Labour’s plans for sustainable investment’, it is actually mostly an appeal to big business for cooperation. There are three strands. Firstly, on the industrial side a strategy of “productive investment to transform Britain” creating 400,000 well paid green jobs. Secondly, a review of the finance system to work out a progressive role for it, under the premise that “of course, the UK is and will remain a hub for finance.” The third strand at least gives some recognition Britain’s historic role and thus “it will be the height of moral irresponsibility if we were to abandon those in the global south to the ravages of climate change.” Flowing from this as an adjunct, “I’ll be convening an International Social Forum where we will be discussing this with activists, economists and environmentalists and others from across the world.”63

James Murray, a ‘business green’ analyst, points out that McDonnell’s proposals are actually “pretty sensible” and close to mainstream thinking, indeed they align with the Bank of England’s own recommendations on TCFD designed to stabilise capital markets (see above). Perceptively, Murray queries whether McDonnell is being radically unradical.64 Whether or not big business and the state establishment will allow a Corbyn/McDonnell led Labour government is genuinely still in doubt. In the meantime, the Labour Party is seeking to channel rebellion into reform. Whatever their past record and even current good intentions, the Corbyn/McDonnell strategy is more about saving the Labour Party than saving the planet. To save the planet it is absolutely clear that Shell, BP and all UK based major fossil fuel companies have to be dismantled: this should be the movement’s condition set on Labour’s International Social Forum.

We return to XR leader Roger Hallam’s strategy, which is more radical than Labour in its form but not in its content: Hallam is for rebellion, not reform; but not revolution either. Hallam has urged popular mobilisation but wants to divert the movement away from any socialistic ending of private ownership of the means of production. Instead Hallam invokes the image of war, of the UK as a nation pulling to together and sharing sacrifice to a common end, as it did in 1939.65 Appealing to the Second World War spirit serves the purpose of national emergency without addressing fundamental system change. Not a war against capital, but a war with capital. The appeal is to blue-green UK climate nationalism. We must all pull together to stop climate change, so no divisive talk about demolishing the multinationals!

While the urge for unity in the face of a common challenge is commendable, it is ridiculous to seek unity with the principal perpetrators and beneficiaries that are driving climate change, Big Oil and Big Mining. The aspiration for unity with them is a strategic mistake that leaves the door wide open for misdirection, cooption and defeat. We should unite, in the direction of international unity to fight against British imperialist corporations and their system, not a spurious national unity that first lets them off the hook and then ends up defending them. Such national unity would be a sham, dividing us from the majority peoples on the frontline of climate change. So there are two distinct paths, nationalist unity or internationalist unity.

System Change: What Strategic Direction?

As the movement prepares for a general climate strike in September we need to be both strategically clear and concrete what we mean by system change. Much of the eco-socialist literature has a utopian strain. We need this vision because to transition off fossil fuel dependency we in the global North will have to completely change our ways of working and living; but even more urgently we need hard analysis of the ways that actually existing capitalism is cajoling financial and technical fixes to somehow refashion itself while the planet fries.

As George Monbiot rightly points out:

Our choice comes down to this. Do we stop life to allow capitalism to continue, or stop capitalism to allow life to continue?66

To stop UK capitalism we must recognise that London especially is a centre of global extractivist capitalism. Alston’s ‘climate apartheid’ is more than a future risk, it is a structural reality with the same source as the original South African apartheid, imperialist capitalism. Being serious must involve a strategy to dismantle the organised destructive power of capitalist Big Oil and Big Mining. Whilst they spin a deceitful narrative, rather than working to stop the climate catastrophe, the UK’s principal capitalist actors will continue to pump out greenhouse gases. That is why to save the planet the UK capitalist class will have to be defeated, it cannot be wished away. A total rupture is needed.

The Amadiba community in Pondoland, South Africa say ‘No To Mining’ of the Xolobeni Sands. Credit: Amadiba Crisis Committee.

What the Labour Party is proposing is worse than a watered down version of the Green New Deal. Indeed, the debate in Britain is moving along similar lines to that in the US, the risk is that mainstreaming will lose the required core of what system change really means, which, “ if it is to be more than words, demands another mode of production altogether.”67

The UK’s bid to host the UN COP26 climate summit in November 2020, billed as the most important since Paris 2015, is backed by business leaders including the bosses of Shell, BP and Drax.68 While agreeing with the positive movement building points made by Nathan Thanki and Asad Rehman in anticipation of COP26,69 we need to centre efforts on a sustained campaign that focuses squarely and definitively on the corporate culprits. We need to create a hostile environment for Big Oil, Big Mining, and the City of London that finances them, with the explicit objective of closing down their imperialist planetary destruction once and for all. We at the privileged end of the extractivist chain have a special responsibility to do this, we have choices and scope for action at the heart of the beast that others do not have.

‘Wretched of the Earth’ contingent on People’s Climate March of Justice and Jobs London, December 7, 2015.

We must not only know our enemy, we must invite our friends. The naming of the pink yacht of Oxford Circus the ‘Berta Cáceres’ was inspired. Berta was assassinated for defending her indigenous community against the ravages of mining destruction.70 This example shows that we can give new internationalist meaning to the environmentalism of the poor. Less high profile but as significant in its way, Colombian refugees joined the XR London Easter protest. They spoke out against the assassination of social and environmental activists, and the persecution of the many women in their country who like Berta are fighting back against the mega-projects stealing nature.71 The representation of people from the Global South should not become merely folkloric, but be part of a conscious strategic bond in which we commit to ending the neo-colonial plunder of their territories by ‘our’ multinationals. What is needed is not Labour’s light Green Industrial Revolution but a dark Green Anti-Imperialist Revolution.

We cannot nudge our way out of the climate crisis. Nor, unlike that manure in Catalonia, will the banks and multinational companies self-ignite. They will cling onto their way of death—mitigating, disclosing and adapting but not really changing anything. For holistic species survival, we need to make Big Oil and Big Mining hit the fan. The Big Fossil corporations are all headquartered within a mile of Whitehall. It is their agenda that has led UK governments for over a century. That’s the rebellion we need, a genuinely internationalist one against the corporations at the extractive imperialist heart of British capitalism. Their extinction as a species is required to save the planet.

Notes

- ↩ India Heat Wave, Now 5th Deadliest on Record, Kills More Than 2,300.

- ↩ Real News Network Climate Change is Devastating India With Heat Waves and Water Shortages,27 June 2019.

- ↩ Cyclone Idai ‘might be southern hemisphere’s worst such disaster’ The Guardian 19 March 2019 ; Cyclone Kenneth Interview OKAfrica, 30 April 2019.

- ↩ Reported on Democracy Now, 28 June 2019.

- ↩ Jem Bendell (2018) Deep Adaptation:A Map for NavigatingClimateTragedy IFLAS Occasional Paper 2.

- ↩ Philip Alston A/HRC/41/39 Climate change and poverty UN Human Rights Council, 25 June 2019.

- ↩ Richard Heede (2014) Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010, Climatic Change 122:229–241, p. 237; and Richard Heede (2013), Supplementary Materials to Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010.

- ↩ With its links to BP, I can’t stay in the Royal Shakespeare Company The Guardian, 21 June 2019.

- ↩ Shell is not a green saviour. It’s a planetary death machine, The Guardian,26 June 2019.

- ↩ BP or Not BP? That is the question.

- ↩ Dare to declare capitalism dead—before it takes us all down with it, The Guardian 25 April 2019.

- ↩ Boris Johnson Beyond Brexit: a Global Britain Speech,2 December 2016, Commonwealth has a key role to play in the bright future for Britain Express,11 March 2018. For discussion see John Smith, Brexit: imperialist Britain faces existential crisis, MROnline, 24 June 2019.

- ↩ Robin McKie Slow burn? The long road to a zero-emissions UK,21 Apr 2019.

- ↩ PwC, 2018 Global Top 100 companies (2018).

- ↩ For fuller reports and analysis see Platform and London Mining Network respectively.

- ↩ Author calculations based on London Stock Exchange (LSE) Group FTSE 100 Stocks Listed in London.

- ↩ ibid p8. We are dealing here with outgoing foreign investments as well as sales. The extent of the overseas contribution to UK profits is even greater once we take into account unequal exchange, for which see John Smith, 2015 Imperialism in the 21st Century and the continual siphoning by the City of London, see Tony Norfield, 2016 The City.

- ↩ LSE, pp. 14, 118.

- ↩ Shell, 2019 Strategic Report: Shell Annual Report 2018, p. 9.

- ↩ BP, 2019a BP Annual Report 2018: Growing the business and advancing the energy transition, p. 17.

- ↩ BP, 2019a, p. 303.

- ↩ Karl Marx, 1981 Capital Volume 3.

- ↩ Shell, 2019, p. 264.

- ↩ BP, 2019a, p. 321.

- ↩ These shareholders are: BlackRock, Inc, 7.2%; The Capital Group Companies, Inc.5.7%; The Vanguard Group, Inc. 4.0%; State Street Nominees Limited, 4.4%; Chase Nominees, 3.9%. Shell, 2019 pp. 25-26; p. 257.

- ↩ BP, 2019a, p. 309.

- ↩ For reports on UK based multinationals, their interests and effects see War on Want (2016) The New Colonialism: Britain’s scramble for Africa’s energy and mineral resources and (2019)The Rivers are Bleeding: British mining in Latin America. Another important connection in Britain’s neo-colonial web is with India, see Foil Vedanta. Critical book length studies of Canada’s role as a hub of mining imperialism include: Alain Deneault and William Sacher (2012) Imperial Canada Inc.: Legal Haven of Choice for the World’s Mining Industries Talon books; Yves Engler Canada in Africa: 300 Years of Aid and Exploitation Fernwood; Todd Gordon and Jeffrey Webber (2017) Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America Fernwood and Tyler Shipley (2017) Ottawa and Empire: Canada and the Military Coup in Honduras Between the Lines.

- ↩ BP, 2019b BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019, p. 8.

- ↩ Global Carbon Atlas. Climate Watch estimates UK greenhouse gas energy emissions in 2014 at 420Mt, with a further 110 Mt from other sources, giving the higher overall figure of 530 Mt.

- ↩ Climate Change Act 2008.

- ↩ Ed Miliband How to save the planet, Prospect, 10 June 2019. Emphasis added.

- ↩ Stanley Cohen, 2001 States of Denial: Knowing About Atrocities and Suffering, Polity.

- ↩ Greta Thunberg, 2019 No One is Too Small to Make a Difference (London: Penguin), p. 62.

- ↩ Bows-Larkin, A., Traut, M., Gilbert, P., Mander, S., Walsh, C., & Anderson, K. (2012). Aviation and shipping -privileged again? (Tyndall Centre Briefing note 47). Manchester: Manchester University, p. 5.

- ↩ Morgan, Nina (2011) Carbon Emission Accounting—Balancing the books for the UK UK Energy Research Centre, p. 2.

- ↩ FAO Stat Data Forestry Production and Trade.

- ↩ Richard Heede , 2014 Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010, Climatic Change 122:229–241; (2013) Supplementary Materials.

- ↩ Paul Griffin, 2017 The Carbon Majors Database: CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017 CDP, p. 8.

- ↩ Ibid, pp. 5-6.

- ↩ James Murray ‘Good news for both investors and the planet’: BP pledges to deliver Paris Agreement consistent strategy Business Green,1 February 2019.

- ↩ BP Greenhouse gas emissions.

- ↩ Rainforest Action Network et al, 2019 Banking on Climate Change 2019, p. 90.

- ↩ See Alfred Crosby, 2004 Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 Cambridge; John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, 2004 ‘Ecological Imperialism: The Curse Of Capitalism’ in Socialist Register 2004: 186-201.

- ↩ Carbon off setting and derivatives are beyond the scope of this article.

- ↩ Rainforest Action Network et al, 2019, p. 12.

- ↩ Lloyds, 2018 ClimateWise Annual Reporting 2017-8.

- ↩ Gillian Tett ‘Central banks are finally taking up the climate change challenge’Financial Times, 25 April 2019.

- ↩“About” Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures(TCFD).

- ↩ See video, ibid.

- ↩ TCFD 2019 Status Report, p. 1.

- ↩ Ibid, p. 5.

- ↩ Ibid, p. 9.

- ↩ See for example David Whyte (2015) (editor) How Corrupt is Britain? Pluto Press

- ↩ The Climate Change Act 2008 (2050 Target Amendment) Order 2019

- ↩ Greg Muttitt, Anna Markova and Matthew Crighton, 2019 Sea Change: Climate Emergency, Jobs and Managing the Phase-Out of UK Oil and Gas Extraction Platform, Oil Change International and Friends of the Earth Scotland, p. 3

- ↩ Ibid, p. 3

- ↩ Ibid, p. 3. Emphasis added.

- ↩ Beyond Politics: Parliament Square.

- ↩ This is Not A Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook, 2019, p. 100.

- ↩ See these different positions in Owen Jones meets Extinction Rebellion: ‘We’re the planet’s fire alarm’ The Guardian, 26 April 2019.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ House of Commons Hansard, Environment and Climate Change,1 May 2019.

- ↩ John McDonnell, Speech on the economy and Labour’s plans for sustainable investment,24 June 2019.

- ↩ James Murray, Radically Unradical? BusinessGreen,25 June 2019.

- ↩ Roger Hallam, So It Has Come To This: Extinction Rebellion Diary #1,6 September 2018.

- ↩ Dare to declare capitalism dead—before it takes us all down with it The Guardian, 25 April 2019.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, Ecosocialism and a Just Transition, 21 June 2019.

- ↩ Fossil fuel bosses at BP, Shell and Drax The Daily Telegraph,29 May 2019.

- ↩ The UN climate talks are coming to Britain. The climate justice movement will be ready

- ↩ Berta Caceres, The Guardian, December 2018.

- ↩ Colombia Solidarity Campaign, Colombian Social Movements: Resisting Extinction, Newsletter, May 2019.