Like nursing homes, the U.S. meatpacking industry has become one of the hotspots of the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Like nursing homes, the U.S. meatpacking industry has become one of the hotspots of the novel coronavirus pandemic.

By 5 May, over 10,000 meatpacking plant workers in 29 states and working at 170 plants had tested positive for the coronavirus. At least 45 of those meat industry workers had died. The outbreaks have prompted at least 40 meat slaughtering and processing plant closures—lasting anywhere from one day to several weeks—since the start of the pandemic.

They should have been closed down and stayed closed, to protect the health and safety of meatpacking workers. But then Donald Trump, on 28 April (the day after John Tyson, the chair of the board of Tyson Foods, published a full-page ad in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette), invoked the 1950 Defense Production Act and designated the meatpacking plants as part of critical infrastructure in the United States. He thus ordered meat processing plants to stay open to protect the nation’s food supply amid the coronavirus pandemic. On top of the fact that production lines necessitate that workers stand very close together, most are low-income, hourly workers, many of them immigrants.

More than a century later, the U.S. meatpacking industry is back to The Jungle.

Upton Sinclair’s famous novel brought the difficult working and living conditions of meatpackers to light. I taught it on a regular basis in my Commodities: The Making of Market Society course, in the section on labor as a commodity. I discovered that Sinclair’s exposé, which was serialized in the socialist magazine Appeal to Reason before it was published as a single volume, had disappeared from high-school reading lists. But when students read it, it opened their eyes to the exploitation of labor in the meatpacking industry, especially when they read passages like these:

It was all robbery, for a poor man. The rich people not only had all the money, they had all the chance to get more; they had all the know-ledge and the power, and so the poor man was down, and he had to stay down . . .

All day long this man would toil thus, his whole being centered upon the purpose of making twenty-three instead of twenty-two and a half cents an hour; and then his product would be reckoned up by the census taker, and jubilant captains of industry would boast of it in their banquet halls, telling how our workers are nearly twice as efficient as those of any other country. If we are the greatest nation the sun ever shone upon, it would seem to be mainly because we have been able to goad our wage-earners to this pitch of frenzy.

Unfortunately, the reception of Sinclair’s graphic descriptions of the meatpacking industry in Chicago focused more on the quality of the food than on the working conditions, causing him later to lament that “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Fortunately, conditions in the meatpacking industry did improve over time, especially when the openly left-wing United Packinghouse Workers of America engaged in a militant battle to organize workers across racial and ethnic lines and to bargain over pay and working conditions with employers. As Meagan Day explains,

For a few decades, thanks to this high degree of worker organization, meatpacking was not one of the most dangerous, difficult, and undercompensated jobs in the United States.

But then the industry itself changed, with the growth of a few very large meat-processing corporations, which in turn decided to move plants to more rural areas, where it was much harder to organize workers.*

Exactly one century after the first installment of Sinclair’s novel appeared, conditions had deteriorated so badly that Human Rights Watch, for the first time in its history, singled out a particular U.S. industry for violating basic human and worker rights. According to its report, “Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Workers’ Rights in U.S. Meat and Poultry Plants,”

Meat and poultry industry companies do not promise rose-garden workplaces, nor should it be expected of them. Turning an eight hundred pound animal or even a five pound chicken into tenders for the supermarket checkout or fast food restaurant counter is by its nature demanding physical labor in bloody, greasy surroundings. But workers in this industry face more than hard work in tough settings. They contend with conditions, vulnerabilities, and abuses which violate human rights.

Employers put workers at predictable risk of serious physical injury even though the means to avoid such injury are known and feasible. They frustrate workers’ efforts to obtain compensation for workplace injuries when they occur. They crush workers’ self-organizing efforts and rights of association. They exploit the perceived vulnerability of a predominantly immigrant labor force in many of their work sites. These are not occasional lapses by employers paying insufficient attention to modern human resources management policies. These are systematic human rights violations embedded in meat and poultry industry employment.

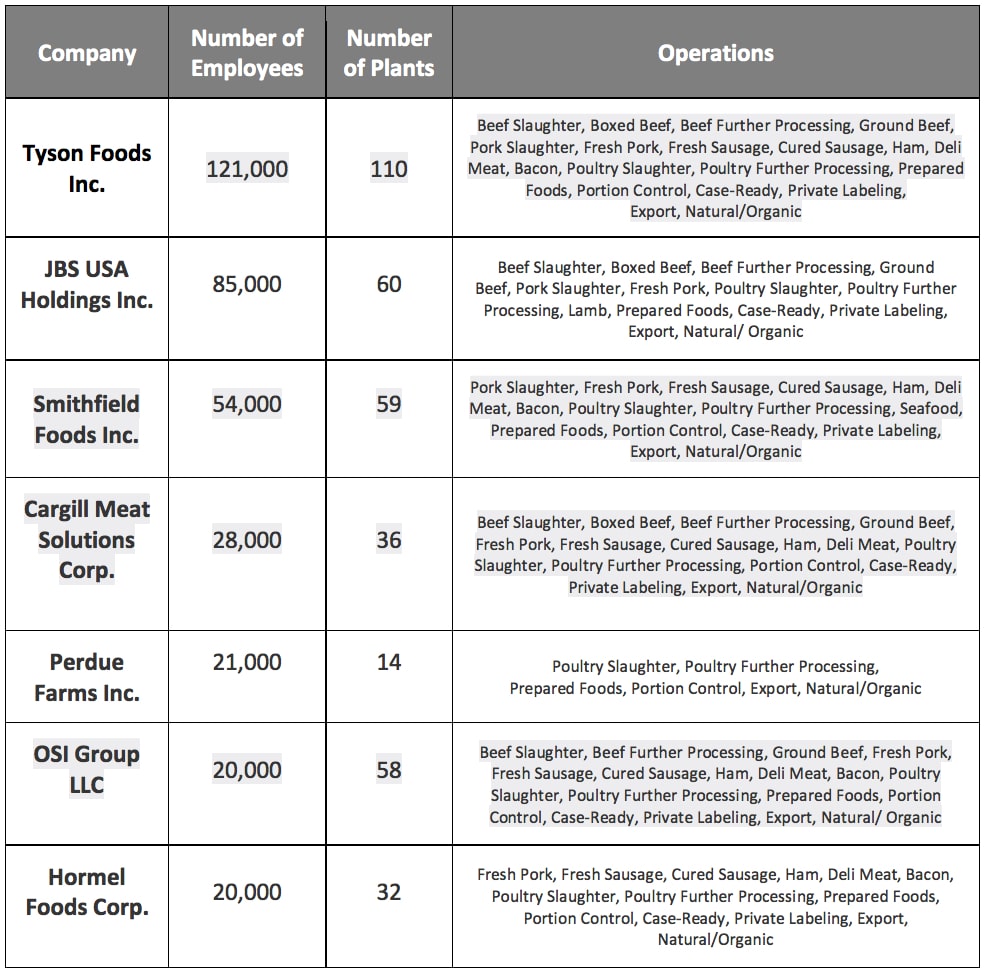

Today, seven companies dominate the industry (according to data from the National Provisioner)—the same companies that have been featured in recent news reports about the growing number of virus infections and temporary plant closures in rural America: Tyson, JBS, Smithfield, and so on.

These corporations and others in the contemporary meatpacking jungle only pay their workers, on average $14.05 an hour or $29,230 a year (median pay for slaughterers and meat packers in May 2019). That’s less than three-quarters (73.4 percent) of the median pay for all occupations in the United States ($19.14 an hour)—and much less even than many other groups of “essential” workers, including bus drivers ($20.69), licensed nurses ($22.83), postal service workers ($25.03), and tractor-trailer drivers ($21.76).

The fact is, even before the pandemic, giant meatpacking companies were more determined than ever to keep labor costs as low as possible and production as high as possible. This meant hiring cheap labor, maintaining intolerably high line speeds, and demanding cuts in wages and benefits from unionized facilities.

And then, once the pandemic was underway and spreading across the country, the meat-processing industry’s failure to protect its workers from the coronavirus triggered the most serious threat to U.S. meat supplies since World War II.

Now as in 1906, safe working conditions are the priority for workers on the meat-processing assembly-lines. The Trump administration has clearly sided with the corporations. The question for the rest of Americans is, are they going to respond to the crisis in the meatpacking industry with their hearts or their stomachs?

*According to union researcher Daniel Calamuci, writing in 2008, the United Packinghouse Workers of America eventually merged with the Amalgamated Meat Cutters in 1968 and, in 1979, they became part of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union. The new union adopted a much less militant stance. For example, when one of its union locals at a Hormel plant in Minnesota went on strike in 1985 to preserve its workers’ high wages, the national organization declined to support it.