On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the extraordinary experience of the Paris Commune, it is fundamental to draw a number of lessons from it. The measures a government takes regarding its Central Bank, the debts of working class people, public debt and private banks are decisive. If a popular government does not implement radical financial measures, it will be responsible for ending in failure, with possibly tragic consequences for the population. The Commune, an extraordinary and dramatic experiment, exemplifies this, and must thus be analyzed from this point of view.

The role of debt in the emergence of the Paris Commune(1)

It was the desire of the reactionary government to pay off its debt to Prussia and continue to repay existing public debts that precipitated the Commune experiment. Let us recall that it was Louis Bonaparte (Napoleon III) who declared war on Prussia in July 1870 and that that military venture soon ended in a total fiasco.(2) The Prussian Army beat the French Army in early September 1870, and imprisoned Napoleon III in Sedan, triggering the fall of the Second Empire followed by the proclamation of the Republic.(3) The payment of 5 billion francs was the condition laid down by Bismarck for signing the peace treaty and withdrawing the forces of occupation.

In a document adopted in solidarity with the Commune on 30 May 1871 by the leadership of the International Workingmen’s Association also known as the First International), Karl Marx emphasizes the enormous burden of public debt that had benefited the French bourgeoisie and weighed heavily on Thiers’ “republican” government that had replaced Napoleon III’s: “The Second Empire had more than doubled the national debt, and plunged all the large towns into heavy municipal debts. The war had fearfully swelled the liabilities, and mercilessly ravaged the resources of the nation.”(4) To that, Marx adds the expenses incurred by the maintenance of half a million Prussian soldiers on French soil, the 5 billion francs of compensation demanded by Bismarck and 5 % interest to be added to that amount in case of delayed payment.

Who was to repay the debt?

Then Marx asks, “Who was to pay this bill?” He replies that from the point of view of the bourgeoisie and Thiers himself, it could only be done by brutally crushing the people, “that the appropriators of wealth could hope to shift onto the shoulders of its producers the cost of a war which they, the appropriators, had themselves originated.” According to Marx, Thiers’ government was convinced that the only way to make the people of France agree to being bled dry to repay the public debt would be to start a civil war, overcome their resistance and force them to foot the bill. Bismarck shared this opinion and was convinced that to bring France to heel and get them to agree to fulfill the conditions laid down by victorious Prussia, the people needed to be crushed, starting with those of Paris. However he did not wish to use the exhausted Prussian Army to do this. He wanted Thiers to do the dirty work.

Thiers had tried and failed to persuade Bismarck to send his troops into Paris.

In order to carry on repaying the national debt which profited the bourgeoisie and to start repaying the war debt, Thiers proceeded to borrow 2 billion francs in the weeks running up to the Commune.(5)

The Paris Commune hold Thiers as a puny new-born baby: “And don’t they want me to acknowledge this little runt!…” Cartoon published in the illustrated magazine Le Fils du père Duchêne issue n°2, “6 Floréal 79” (CC – Wikimedia)

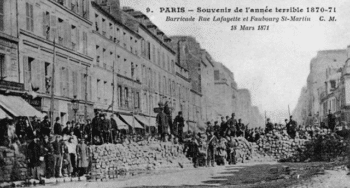

To put down the people of Paris who were armed, Thiers mounted a military operation on 18 March 1871 to steal 400 of their cannons and machine guns. It was the failure of this attempt that led to popular mobilization and ended up with Thiers’ government fleeing and setting up in Versailles. Those in charge of the Communards made the mistake of not pursuing Thiers and his government. They should have fetched him from Versailles, detained him and thus prevented the government from regrouping their troops and sending them out later against the people of Paris and the other cities which took part in the uprising.(6) Versailles, in the following days and weeks, Thiers organized the crushing of the Communes as soon as they emerged in different parts of France (Marseille, Lyon, Narbonne, Saint-Etienne, Toulouse, Le Creusot, Limoges…). Even as he used the part of the Army he had at his disposal to put down the Communes in the South of France, Thiers made as though to negotiate with the Paris Commune to gain time and prepare for a final offensive against it. This led to a delegation from Thiers’ government being sent to Frankfurt at the beginning of May 1871 to ask Bismarck for help in crushing the Paris Commune. Bismarck replied that they should first pay the instalments due on the debt and that to help them create the right conditions for victory, he would allow Thiers to use the part of the French Army that the Prussians were holding prisoner to attack Paris. Bismarck also agreed to send part of the Prussian troops as back-up though they were not to enter Paris. Finally, after long negotiations, Bismarck agreed to wait until the Paris Commune had been dealt with before receiving the first payment.(7) This was the plan concocted between the French government and the Prussian leader that finally overcame the Paris Commune.

The remainder of this article concentrates on the Commune’s policy regarding rent and the debts of the working classes on the one hand, and the Bank of France on the other.

The Commune’s positive measures dealing with rent and other debts

On 29 March 1871, the Commune decided to suspend payment of rent, including rent owed since October 1870. Another measure taken on the same day in favour of the people was to ban pawn-brokers from selling pawned items.(8) Pawn-shops (known as Monts-de-Piété) were private bodies that made their profit from secure loans using personal property as collateral.(9)

Should a person who had deposited an item in exchange for a loan not repay their debt, the pawn-broker was entitled to sell the pawned object.(10) Over a million objects accumulated in the pawn-shops. After a particularly harsh winter, poor households had pawned eighty thousand blankets in order to borrow money to buy food.(11) 73% of pawned items belonged to working people. Of one and a half million loans in a year, two thirds, that is one million, were loans of just 3 to 10 francs. At the end of April 1871, after long debates between moderates and radicals, the Commune decided that people who had acquired a secured loan of less than 20 francs could recover their goods free of charge. The most radical of the elected representatives, like Jean-Baptiste Clément, author of famous songs including Le Temps des Cerises and La Semaine Sanglante, considered that the Commune should have done more, more quickly, in dealing with pawn-shops and in many other aspects of the living conditions of the working classes.(12)

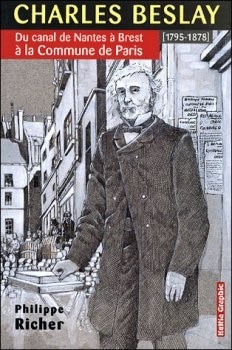

Among those advocating a very moderate approach regarding working-class and middle-class debt (which affected a huge number of small shop-keepers and artisans) was Charles Beslay, the oldest member of the 1871 Commune, a disciple and close friend of Proudhon. Beslay systematically stood up in defence of Finance and creditors. He will be mentioned further on in the section devoted to the Commune’s policy regarding the Bank of France. However, mention should be made of the Commune’s decisions on 25 April to requisition empty housing for the victims of bombing by the troops of Versailles, then on 28 April to forbid employers from levying fines and making deductions from wages.(13)

The Paris Commune made a fatal error in not taking control of the Bank of France

The head-quarters of the Bank of France, its principal reserves and its governing body were situated in Paris Commune territory. The leadership of the Paris Commune made the grave error of not taking it over, which would have been a necessary step.

In his Histoire de la Commune de 1871 published in 1876, Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, a militant intellectual who participated in the Communards’ street fighting, fustigated the Commune’s leaders who were “mesmerized in front of the haute bourgeoisie’s cash-box when they had it in their hands”(14) meaning the Bank of France.

The Commune’s only demand from the Bank of France was to receive the financial advances they needed to maintain a fiscal balance while still paying wages to the National Guardsmen. Paris’s National Guard was a citizens’ militia in charge of law and order and of military defence. It consisted of 300,000 armed personnel for Paris’s population of two million.

The Bank of France barely loosened its purse-strings in response to the financial needs of the Commune whilst it financed generously those who wanted to crush the people of Paris and put a hasty end to the social revolution. During the two months of the Commune experiment, Thiers’ reactionary government, in collusion with the Prussian occupier, received 20 times more cash than the Commune.(15)

Karl Marx thought that the Commune had been wrong not to get hold of the Bank of France:“The appropriation of the Bank of France alone would have been enough to dissolve all the pretensions of the Versailles people into terror.” He wrote that had the Bank been requisitioned,

[W]ith a small amount of sound common sense, however, they could have reached a compromise with Versailles useful to the whole mass of the people–the only thing that could be reached at the time.(16)

In Lissagaray’s words,

the Commune could not see the real hostages it could have taken: the Bank of France, the Real Estate Register (Enregistrement et les Domaines), the State bank handling official deposits or CDC (Caisse des dépôts et consignations), etc.(17)

In 1891, Frederick Engels similarly wrote,

The most difficult thing to understand is, indeed, the sacred respect with which the Commune reverently stopped before the portals of the Bank of France. This was also a portentous political error. The Bank in the hands of the Commune–that was worth more than ten thousand hostages. It would have meant the pressure of the entire French bourgeoisie on the Versailles government in the interests of peace with the Commune.(18)

The leaders of the Paris Commune essentially enabled the Bank of France to finance their own enemies–that is, the conservative government of Thiers at Versailles and its army, which would crush their movement.(19) As we shall see farther on, the Bank of France also financed the Prussian army of occupation that was at the gates of Paris.

Sequence of events concerning the Bank of France and an attempted explanation

In forming an opinion on the attitude of the Commune toward the Bank of France, I have relied mainly on two narratives–the one already cited in this article by Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, who was a firm partisan of the cause of the Commune, and that of Maxime du Camp, an anti-Communard author whose reactionary writings were to earn him election as a member of the Académie française(20) in 1880. The two authors provide many details on the behaviour of the various protagonists, and despite the fact their points of view are diametrically opposed, their narrative is largely in agreement.

Let us follow the sequence of events.

On 18 March, Thiers, his government and his administration fled to Versailles. A few days later Gustave Rouland, governor of the Bank of France, joined them in order to be of service, leaving the vice-governor of the bank, Marquis Alexandre De Plœuc, and his administration in Paris. Among Rouland’s entourage in Versailles were the regents of the Bank of France, who included Baron Alphonse de Rothschild, owner of the Banque Rothschild, the Bank of France’s largest shareholder.

Gustave Rouland wanted to convince Thiers to attack the Paris Commune immediately, but Thiers felt it was necessary to stall for time.

Meanwhile, on 30 March 1871, the Commune had appointed the Proudhonian Charles Beslay as its representative before the Bank of France. Beslay summed up his actions in a letter to the right-wing daily Le Figaro, published 13 March 1873:

I went to the Bank with the intention of preserving it from any violence on the part of the radical elements of the Commune, and it is my conviction that I have saved for my country the establishment that was our last financial resource.(21)

Charles Beslay had been elected to the Commune’s Council on 26 March 1871 and was its oldest member. He had also been a member of the First International (IWA) since 1866. He had great influence in the Commune. Yet Beslay had a capitalist past: he had founded a factory that employed 200 men and women, which in the mid-19th century was a large company.(22) Lissagaray, who had lived through the events of the Commune and had studied the minutes of the sessions of the Commune’s Council, writes that Beslay, from the start, accepted the position defended by the Marquis de Plœuc, which was that the Commune could not appoint the governor of the Bank of France. It was limited to having a delegate, who was Beslay himself. Lissagaray tells us that

Beslay, deeply moved, hurried off to the Executive Commission, repeated his lesson all the better that he believed it and prided himself on his financial lore. ‘The bank,’ he said, ‘is the fortune of the country: without it, no more industry, no more commerce. If you violate it, all its notes will be so much waste-paper.’(23)

This pessimistic and paralyzing conviction was held by a majority within the leadership of the Commune, and its effects were to be tragic.

As Georges Beisson writes: “During its 72 days of existence, the Commune received 16.7 million francs: the 9.4 million that the City of Paris had in its account and 7.3 million that were actually lent by the bank. Meanwhile the Versaillais received 315 million francs […] from the Bank of France,” or nearly 20 times as much.(24)

The reactionary Maxime du Camp agrees when he writes that “Whilst the Commune was harassing the Bank of France in Paris for a few thousand-franc notes, the Bank of France was giving millions to the legal government. The troops were arriving, forming units and organizing, and there was no shortage of wages for them.”(25) The troops Du Camp is referring to are the ones raised by Thiers, with Bismarck’s aid, to destroy the people of Paris. As Du Camp adds,

When Thiers needed money, he informed Rouland, who sent a telegraphic dispatch, and the money arrived.

The Commune had an urgent need of funds to aid the population and to strengthen its defence against imminent attack, but its representatives Beslay and Jourde settled for a pittance. And yet in the vaults of the Bank’s head office in Paris there were banknotes, coins, bullion and financial securities worth approximately three billion francs.

Until the end, the Commune allowed the executives of the Bank of France to have their own, heavily armed militia. The Marquis de Plœuc had several hundred persons under his command who had at their disposal inside the Bank an arsenal made up of hundreds of rifles and ammunition to withstand a siege. Had the Commune actually wished to do so it could have disarmed this militia without firing a shot. But Beslay was totally opposed to the idea.

Maxime du Camp also writes that the Bank’s governor, Rouland, had sent the following message to the bank’s employees:

Please give precise instructions for banknotes to be made available to the Germans, and also some cash for paying their troops.(26)

Du Camp explains that the Marquis de Plœuc told Jourde, the second delegate of the Commune to the Bank, a boldfaced lie. Du Camp reconstitutes a dialogue between them based on first-hand reports:

You think us rich,’ said M. de Plœuc, ‘but we are not; you know very well that when the German troops were marching on Paris, we sent all our holdings away; they have not returned. I am not fooling you; the transfers are easy to track […] and you will be convinced that the majority of our fortune is in the provinces.’–‘Well, my God! Monsieur le Marquis,’ Jourde answered, ‘I know that very well, but if you advance me the money, the Bank will be protecting itself and helping me to save it, which would be impossible without it.’

Within the Commune, advocates of Auguste Blanqui (who was imprisoned by the Thiers government), including Raoul Rigault, were increasingly unhappy with the policy adopted by Beslay, which was supported by Jourde and a majority, and on 12 May 1871 they decided to act and attempted to move on the Bank of France with two companies of the National Guard. But Beslay successfully stepped in in extremis to protect the bank and prevent the seizure. Maxime du Camp concludes: “In this matter old Beslay was really beyond reproach.”(27) This abortive attempt by the Blanqui camp had been conceived as a sort of coup and was not part of a coherent vision aimed at enabling the Commune to use the Bank of France to organize its defence and finance a development plan. Of course the Bank would have had to be taken over “militarily,” but it had to be done for a purpose, and the Blanquistes did not know exactly what that purpose was. They did not propose in the Commune’s Council (where they held seats) that the Bank of France be taken over and used in the service of a plan for resistance and development. They limited their efforts to attempting to take the Bank by surprise, which did not work since the Blanqui faction did not have arguments for overcoming Beslay’s opposition. And so the initiative turned into a fiasco. Note that taking over the Bank of France “militarily” does not mean using artillery, machine guns and rifles. What it does mean is making the decision, at the level of the leadership of the Commune, to take over control of the Bank and remove its governor and vice-governor, bring in a sufficient number of battalions of the National Guard to surround the Bank and demand that its armed occupants lay down their weapons. The disproportion between the forces and the certainty of the Bank’s occupants that they would lose the battle if they resisted would have been enough to ensure their docility. They would have had no hope of reinforcements, at least until the start of the “Bloody Week” on 21 May. The Commune should have taken control of the Bank of France during the first days of its existence.

Probably victims of the repression againt the Paris Commune, Père-Lachaise Cemetery, 1871 (https://macommunedeparis.com/2020/05/11/11-avril-1871-inhumations-sans-mandat-au-pere-lachaise/)

The Commune had every intention of issuing its own currency, and did have currency issued at the Paris Mint–the Hôtel des Monnaies on the Quai Conti –, but it lacked the gold and silver ingots that were stored at the Bank of France. And there again the Bank’s officials were able to count on Beslay’s aid in seeing to it that only miniscule quantities of precious metals were released to be struck into coins.

Maxime du Camp explains that the officials of the Bank of France were so afraid that the radical elements of the Commune would win out over Beslay that they moved everything they could into the cellars of the bank in Paris and packed the only stairway leading down there with sand. The operation took place on 20 May and took some 15 hours. Once all the ingots, coinage, notes, securities and ledgers had been moved into two rooms below ground protected by twelve locks, the spiral stairway leading to the rooms was packed with sand and a slab was laid over it.(28)

The following day, the Bloody Week began, and ended in the defeat of the people of Paris on 28 May 1871.

After the Commune was crushed, Beslay was one of the only Communard leaders (and possibly the only one) who was not executed, sentenced in absentia, imprisoned or exiled. The Commune’s murderers allowed him to go to Switzerland to settle the inheritance of one of his sisters who had died in August 1870, and on 9 December 1872 charges against him were dismissed by the 17th War Council. Toward the end of his life in Switzerland he also served as executor of Proudhon’s will.

The Commune’s attitude toward the Bank of France can be explained by the limitations inherent in the strategy of its majority factions–that is, advocates of Proudhon(29) and of Blanqui. Proudhon, who had died in 1865, was not able to take part directly in the choices, but his supporters were influential. Beslay was far from being the only one. Proudhon, and later his followers, were opposed to having a people’s government take control of the Bank of France. Further, they were against expropriating the capitalist banks; their priority was the creation of credit unions. The role they played, via Beslay, was frankly obstructive.

The supporters of the intransigent Auguste Blanqui were also numerous, and had no specific position as to what needed to be done concerning the Bank of France and the role it should have played in a revolutionary government.

Few of the militants were inspired by the ideas of Karl Marx, even if some of them, such as Léo Frankel, did hold responsibilities and were in regular contact with Marx, who was then living in London. Frankel was a member of the Commission du travail et de l’échange (Committee for Labour and Exchanges). We might also mention Charles Longuet(30), who like Frankel was a member of the la Commission du travail et de l’échange; Auguste Serraillier, a member of the same Commission; and Elisabeth Dmitrieff, who during the Commune was co-foundress of the Union des Femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés (Women’s Union to Defend Paris and Care for the Wounded).

A government of the people must adopt a radical solution regarding the central bank, public debt and private banks

Barricade at the entrance of rue de la Roquette, place de la Bastille–March 1871 (https://macommunedeparis.com/2016/07/15/histoire-de-jules-mottu-3-le-18-mars-la-commune-le-radical/)

The policy adopted by Beslay is highly relevant today. If a government of the people limits itself to proposing or implementing credit unions (cooperative banks) while maintaining the central bank as it now functions in the contemporary State, without socializing the banking sector through expropriation of capitalists, nothing will change at the structural level.

If public debt is not radically reduced, the new government will have no real leverage for financing major changes.

Several lessons to be learned from the Paris Commune

Marx and Engels had drawn several lessons from the Commune. The need to destroy the capitalist State headed the list. Democratic operation of the government and popular representation with revocability of all delegates was another. A refusal to take a sacrosanct attitude toward finance is a third: a popular government must take control of the central bank and change the nature of property relations in the entire financial sector, which implies expropriating the capitalists. A fourth lesson is closely related to the third: the need to cancel public debt. As a matter of fact a few years after the Commune, Marx–who participated in writing the programme of the Parti Ouvrier (Workers’ Party) in France–spoke of the need for “Suppression of the public debt” (see “The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier” www.marxists.or)

The resolute action taken by Soviet Russia and the Cuban revolution regarding the central bank, banks and deb

The Bolsheviks in Russia and the Cuban revolutionaries had learned these lessons and took the necessary measures in 1917–1918, in the case of the decrees adopted by the Soviets, and in 1959–1960 in the case of the Cuban revolution. The government of the Bolsheviks, allied with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries with the support of the workers’, peasants’ and soldiers’ councils (Soviets) took control of the central bank, issued their own currency, expropriated the bankers, cancelled the peasants’ debts and repudiated all debt contracted by the Tsarist regime.(31) The revolutionary Cubans took control of the central bank, placed Che Guevara at its head, issued their own currency and cancelled public debt. As regards the right to housing, they went much farther than the Commune, and also decreed that tenants should be allowed to continue occupying their living quarters without paying rent.(32) The Bolsheviks also implemented a solution to the problem of housing and related indebtedness.

The lessons of the Paris Commune have been largely forgotten

In a broader sense, the lessons of the Paris Commune have been largely forgotten. First, the Social Democrat movement, after its betrayal of Internationalism at the start of the First World War, became an instrument of capitalist and imperialist domination; then, dictatorial bureaucratic and Stalinist regimes, with the restoration of capitalism, perpetuated brutal forms of coercion and exploitation; more recently, progressive regimes in Latin America at the start of the 21st century have remained within a capitalist framework by maintaining and extending a development model focused on exportations, exploitation of natural resources and a policy of low wages in the name of competitiveness–although admittedly they have practised a policy of assistance which did reduce poverty in the early years. One positive point is that the constitutions of Venezuela (1999), Ecuador (2008) and Bolivia (2009) include the principle of revocability of all mandates of elected representatives.

Concerning the question of central banks, private banks and the finance sector in general, one can only notice an extremely serious impoverishment of the programmes of organizations who claim to be radically socialist. In 2019, the Manifesto of the Labour Party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, although radical as regards a number of issues such as re-nationalizations and cancellation of student debt, says nothing about the City of London and the Bank of England; Bernie Sanders’s 2019-2020 platform, radical in the areas of taxes and student debt, was also silent as regards the central bank (the Fed) and the big private banks. The programmes of other political organizations such as Podemos, DiEM25,(33) and Die Linke are either silent or else take a moderate and therefore inappropriate attitude towards the question of the central bank, big private banks, currency and public debt.

Greece 2015 or the failure of the moderate approach

Action should have been taken to deal with the banks as soon as the Tsipras government was put in place. With the ECB taking the initiative to worsen Greece’s banking crisis, action should have been taken as provided for in the Thessaloniki Programme, on the basis of which the Syriza government was elected on 25 January 2015 and which stated: “With Syriza in government, the public sector will take over control of the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF) and exercise all its rights over the recapitalized banks. That means that it will make decisions about the way they are run.” Keep in mind that in 2015 the Greek State, via the HFSF, was the principal shareholder of the country’s four largest banks, accounting for over 85% of Greece’s entire banking sector. The problem is that despite the numerous successive recapitalizations of Greek banks since October 2008, the State had no real weight in the banks’ decisions since the shares it held did not entitle it to voting rights, as no previous government had made the necessary political decision. That being the case, the Parliament, in conformity with Syriza’s commitments, should have turned the so-called preferential shares (having no voting rights associated with them) held by the public authorities into common shares with voting rights. Then the State, in a perfectly normal and legal way, would have been able to exercise its responsibilities and provide a solution to the banking crisis.

Lastly, five other important measures needed to be taken.

Primo, to face the banking and financial crisis that had been exacerbated by the attitude of the Troika (the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF) since December 2014, which noisily warned of bank failures, and by the ECB’s decision of 4 February 2015,(34) the government should have implemented oversight over capital movements in order to end flight of capital abroad. Secundo, payments of external public debt should have been suspended with immediate effect. Thirdly, the Governor of Greece’s Central Bank should have been replaced and it should have been taken over in the name of the people. Fourthly, the government should have set up a complementary currency and prepared to exit the euro. Fifthly, it should have cancelled all working-class debts to private banks and the State.(35)

The decision made by Prime Minister Tsipras and Finance Minister Varoufakis not to touch the private banks, to leave the former Governor of the Greek Central Bank in office, not to control capital flows and not to suspend repayment of the debt had dire consequences for the Greek people. To paraphrase Friedrich Engels’ words about the Paris Commune, Tsipras and Varoufakis showed a sacred respect towards finance, they stopped before the portals of the Central Bank and the private banks. A historic opportunity was missed. That should not be allowed to happen again in the world.

The decision made by Prime Minister Tsipras and Finance Minister Varoufakis not to touch the private banks, to leave the former Governor of the Greek Central Bank in office, not to control capital flows and not to suspend repayment of the debt had dire consequences for the Greek people. To paraphrase Friedrich Engels’ words about the Paris Commune, Tsipras and Varoufakis showed a sacred respect towards finance, they stopped before the portals of the Central Bank and the private banks. A historic opportunity was missed. That should not be allowed to happen again in the world.

Conclusion

A popular government cannot sit back and do nothing in face of the world of Finance. It must take radical measures regarding its Central Bank, private banks and debt. If it does not do so, it is condemned to failure.

The author would like to thank Virginie de Romanet, Brigitte Ponet, Claude Quemar and Patrick Saurin for reading the text. He also thanks Hans Peter Renk and Claude Quemar for help with documentary research.

Appendix 1. Some illustrations of measures regarding finance taken by governments in capitalist countries

In 1933 President F. D. Roosevelt took a strong measure towards U.S. banks, which other governments emulated after WWII, notably in Europe.

In the U.S. in March 1933 an unprecedented bank crisis broke out in the wake of the Wall Street crash on October 1929. The newly elected president, Franklin Roosevelt, closed the banks for a week in March 1933 and had the Banking Act (also known as Glass Steagall Act) voted the same year; it enforced the separation between commercial and investment banks.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s government thus infringed on the total freedom so far enjoyed by the financial and banking community. In the wake of this decision and under pressure of popular mobilizations in Europe during and after the Liberation at the end of World War II, the old continent’s governments forced a limitation to the freedom of manœuvering enjoyed by capital.

As a consequence, during the ensuing thirty years, there were a very limited number of bank crises. This is shown by two U.S. neoliberal economists, Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, in This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (2009). Kenneth Rogoff was the IMF’s chief economist and Carmen Reinhart, a university professor, has also held influential positions with the IMF and was chief economist at Bear Stearns. According to those two economists, who definitely do not wish to question capitalism, the low number of bank crises can be explained “by the repression of the domestic financial markets (in varying degrees) and the heavy-handed use of capital controls that followed for many years after World War II.”

In fact, during the post-war boom, the governments of the majority of the most industrialized countries had policies of regulation of capital movements from or to their countries. They also required banks to behave prudently and moved a part of the financial industry to the public sector. According to Reinhart and Rogoff, in order to avoid the risk of bank failures, governments imposed “high requirements for bank reserves, among other devices, such as directed credit and minimum requirements for holding government debt in pension and commercial bank portfolios.”

After the Liberation the government nationalized the Bank of France and other banks

In France, the nationalizations of banks at the end of the Second World War must “be seen in the context of the Resistance with ‘a movement from below’ […] the Liberation gave rise to the establishment of workers’ managing committees in certain companies and works councils who originated ‘spontaneous socialisations’.” As Patrick Saurin points out, on 2 December 1945 the Bank of France and four custodian banks were nationalized. The following year, on 25 April 1946, certain insurance companies were also nationalized.

Benjamin Lemoine correctly writes in his book L’ordre de la dette:

At the end of the Second World War and for more than twenty years thereafter, the apparatus of the State, via what was called the Treasury Circuit (Circuit du Trésor), collected a sufficient mass of financial resources to escape from pressure from creditors in most cases. It controlled the activity of the banks and finance and bound its own treasury instruments to those regulations. Similarly, its financing was coordinated with national policies fixing currency quantities and orienting the credits set aside for the economy.

Such policy made it possible for France to finance itself for almost forty years without being dependent on financial markets, controlled by private banks and other financial companies. It also prevented banking crises.

The nationalization of banks in India in 1969

From India’s independence in 1947 to 1969, the Indian banking sector was dominated by private banks. Those years were marked by numerous banks going bankrupt. In 1969, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi made a move towards more State intervention and a stronger public sector (a move that led to a break with the right-wing of her party, the Indian National Congress). She was actually attempting to boost Indian capitalism and to meet some popular expectations. One of the measures she took in 1969 was to nationalize fourteen banks. Among other measures, she put an end to some privileges granted to principalities and inherited from the colonial era when British power maintained maharajahs in token power.

In her own way, Indira Gandhi acted as the De Gaulle government had in France after the Second World War, which was called the ‘Treasury Circuit’ (circuit du Trésor). Indian public banks had to deposit the equivalent of 20% of their assets with the Central Bank as a guarantee against the risk of defaulting. They had to devote 40% of their assets to buying public debt securities, gold or cash. The remaining 40% had to be allocated as credits according to specific standards, which gave a significant position to farmers, artisans and small and medium-sized companies.

France, 1982: Second nationalization of the banks

The nationalization plan was part of the Programme Commun de Gouvernement or joint governmental program signed on 27 June 1972 between France’s Socialist, Communist and Radicaux de gauche parties. It was among the “110 Proposals” of presidential candidate François Mitterrand in 1980-81 (Proposal 21). The Nationalization Law of 13 February 1982 was adopted during President Mitterrand’s first seven-year term and promulgated by the government of Prime Minister Pierre Mauroy. Thirty-nine banks were nationalized, along with certain industrial and financial companies. [20] This wave of nationalizations was quickly followed by a swing to the right by Mitterrand and his government. The Banking Law of 24 January 1984 inaugurated a new banking system, built on the model of the universal bank, which ended the separation between retail banks and investment banks and fully opened the door to deregulation. In 1986, the banks were re-privatized.

In Europe and the USA, in the wake of the 2007-2008 crisis, many banks were bailed out

Following the crisis of the private banks that broke out in 2007–2008, several governments of major countries nationalized very large private banks in order to avoid failure and come to the aid of the banks’ major shareholders. Major banks such as the Royal Bank of Scotland (UK), Hypo Real Estate (Germany), ABN-Amro in Holland, Fortis, Dexia and Belfius in Belgium, Bankia in Spain, Banco Espírito Santo in Portugal and others were nationalized. In not a single one of these cases did the public authorities reorient the activities of the nationalized entities for the benefit of the respective populations. Often, they did not even have any power within the institutions, which remained entirely under the direction of representatives of the private sector. None of these banks were turned into instruments for financing investments by the State. The costs of nationalization were borne by the public finances and resulted in increased public debt. The next phase, as foreseen by the governments acting in the service of capital, will consist in re-privatizing these banks once their finances have been cleaned up and they again become attractive to the private sector. The CADTM and other organizations had promoted another way of responding to the banking crisis: refuse to save the bankers who were responsible for the crisis, expropriate the banks without paying compensation to their major shareholders and transfer them to the public sector under citizen control.

Source: Excepts from Éric Toussaint, Some historical illustrations of decisive actions relative to banks Paris Commune, Russian revolution, F.D. Roosevelt, De Gaulle, Mitterrand, 16 August 2020, www.cadtm.or. The part on India is unpublished.

Appendix 2. Frederick Engels’s summary of the various measures taken by The Commune

. . . Thiers, the new head of government, was compelled to realize that the supremacy of the propertied classes–large landowners and capitalists–was in constant danger so long as the workers of Paris had arms in their hands. His first action was to attempt to disarm them. On March 18, he sent troops of the line with orders to rob the National Guard of the artillery belonging to it, which had been constructed during the siege of Paris and had been paid for by public subscription. The attempt failed; Paris mobilized as one man in defence of the guns, and war between Paris and the French government sitting at Versailles was declared. On March 26 the Paris Commune was elected and on March 28 it was proclaimed. The Central Committee of the National Guard, which up to then had carried on the government, handed in its resignation to the National Guard, after it had first decreed the abolition of the scandalous Paris “Morality Police.” On March 30 the Commune abolished conscription and the standing army, and declared that the National Guard, in which all citizens capable of bearing arms were to be enrolled, was to be the sole armed force. It remitted all payments of rent for dwelling houses from October 1870 until April, the amounts already paid to be reckoned to a future rental period, and stopped all sales of articles pledged in the municipal pawnshops. On the same day the foreigners elected to the Commune were confirmed in office, because “the flag of the Commune is the flag of the World Republic.”

On April 1 it was decided that the highest salary received by any employee of the Commune, and therefore also by its members themselves, might not exceed 6,000 francs. On the following day the Commune decreed the separation of the Church from the State, and the abolition of all state payments for religious purposes as well as the transformation of all Church property into national property; as a result of which, on April 8, a decree excluding from the schools all religious symbols, pictures, dogmas, prayers–in a word, “all that belongs to the sphere of the individual’s conscience”–was ordered to be excluded from the schools, and this decree was gradually applied. On the 5th, in reply to the shooting, day after day, of the Commune’s fighters captured by the Versailles troops, a decree was issued for imprisonment of hostages, but it was never carried into effect. On the 6th, the guillotine was brought out by the 137th battalion of the National Guard, and publicly burnt, amid great popular rejoicing. On the 12th, the Commune decided that the Victory Column on the Place Vendôme, which had been cast from guns captured by Napoleon after the war of 1809, should be demolished as a symbol of chauvinism and incitement to national hatred. This decree was carried out on May 16. On April 16 the Commune ordered a statistical tabulation of factories which had been closed down by the manufacturers, and the working out of plans for the carrying on of these factories by workers formerly employed in them, who were to be organized in co-operative societies, and also plans for the organization of these co-operatives in one great union. On the 20th the Commune abolished night work for bakers, and also the workers’ registration cards, which since the Second Empire had been run as a monopoly by police nominees–exploiters of the first rank; the issuing of these registration cards was transferred to the mayors of the 20 arrondissements of Paris. On April 30, the Commune ordered the closing of the pawnshops, on the ground that they were a private exploitation of labor, and were in contradiction with the right of the workers to their instruments of labor and to credit. On May 5 it ordered the demolition of the Chapel of Atonement, which had been built in expiation of the execution of Louis XVI.

Source: Frederick Engels’ Introduction to Marx, The Civil War in France (1871), p. 16. An integral version of the book is available at www.marxists.org

Appendix 3. Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray on the Commune and the Bank of France

In allowing the Versaillese army to march off, the Central Committee had committed a heavy fault; that of the Council was incomparably more damaging. All serious rebels have commenced by seizing upon the sinews of the enemy–the treasury. The Council of the Commune was the only revolutionary Government that refused to do so. While abolishing the budget of public worship, which was at Versailles, they bent their knees to the budget of the bourgeoisie, which was at their mercy.

Then followed a scene of high comedy, if one could laugh at negligence that has caused so much bloodshed. Since the 19th March the governors of the bank lived like men condemned to death, every day expecting the execution of the treasure. Of removing it to Versailles they could not dream. It would have required sixty or eighty vans and an army corps. On the 23rd, its governor, Rouland, could no longer stand it, and fled. The deputy governor, De Ploeuc, replaced him. From his first interview with the delegates of the Hôtel-de-Ville he had seen through their timidity, given battle, then seemed to soften, yielded little by little, and doled out his money franc by franc. The bank, which Versailles believed almost empty, contained: coin, 77 million; [117] bank-notes, 166 million; bills discounted, 899 million; securities for advances made, 120 million; bullion, 11 million; jewels in deposit, 7 million; public effects and other titles in deposit, 900 million; that is, 2 milliards 180 million francs: 800 million in bank-notes only required the signature of the cashier, a signature easily made. The Commune had then three billion in its hands, of which over a billion was realized, enough to buy all the generals and functionaries of Versailles; as hostages, 90,000 depositors of titles, and the two billion in circulation whose guarantee lay in the coffers in the Rue de la Vrillière.

On the 29th March old Beslay presented himself before the tabernacle. De Ploeuc had mustered his 430 clerks, armed with muskets without cartridges. Beslay, led through the lines of these warriors, humbly prayed the governor to be so kind as to supply the pay of the National Guard. De Ploeuc answered superciliously, spoke of defending himself. ‘But,’ said Beslay, ‘if, to prevent the effusion of blood, the Commune appointed a governor. . . “A governor! Never!’ said De Ploeuc, who understood his man; ‘but a delegate! If you were that delegate we might come to an understanding.’ And, acting pathetic, ‘Come, M. Beslay, help me to save this. This is the fortune of your country; this is the fortune of France.’

Beslay, deeply moved, hurried off to the Executive Commission, repeated his lesson all the better that he believed it and prided himself on his financial lore. ‘The bank,’ he said, ‘is the fortune of the country: without it, no more industry, no more commerce. If you violate it, all its notes will be so much waste-paper. [118] This trash circulated in the Hôtel-de-Ville, and the Proudhonists of the Council, forgetting that their master put the suppression of the bank at the head of his revolutionary programme, backed old Beslay. At Versailles itself, the capitalist stronghold had no more inveterate defenders than those of the Hôtel-de-Ville. If someone had at least proposed, ‘Let us at least occupy the bank’–but the Executive Commission had not the nerve to do this, and contented itself with commissioning Beslay. De Ploeuc received the good man with open arms, installed him in the nearest office, even persuading him to sleep at the bank, made him his hostage, and once more breathed freely.

Thus from the first week the Assembly of the Hôtel-de-Ville showed itself weak towards the authors of the sortie, weak towards the Central Committee, weak towards the bank, trifling in its decrees, in the choice of its delegate to the War Office, without a military plan, without a programme, without general views, and indulging in desultory discussions. The Radicals who had remained in the Council saw whither it was drifting, and, not inclined to play the martyrs, they sent in their resignations.

Source: Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871, translated by Eleanor Marx, Chapter XIV “The weaknesses of the Council” www.marxists.org

Appendix 4. Timeline of The Civil War in France and of the Paris Commune

1870

- January 10: About 100,000 people demonstrate against Bonaparte’s Second Empire after the death of Victor Noir, a republican journalist killed by the Emperor’s cousin, Pierre Bonaparte.

- May 8: A national plebiscite votes confidence in the Empire with about 84% of votes in favour. On the eve of the plebiscite members of the Paris Federation of the International Working Men’s Association were arrested on a charge of conspiring against Napoleon III. This pretext was further used by the government to launch a campaign of persecution of the members of the International throughout France.

- July 19: After a diplomatic struggle over the Prussian attempt for the Spanish throne, Louis Bonaparte declares war on Prussia.

- July 23: Marx completes what will become known as his “First Address.”

- July 26: The “First Address” is approved and internationally distributed by the General Council of the International Working Men’s Association.

- August 4-6: Crown Prince Frederick, commanding one of the three Prussian armies invading France, defeats French Marshal MacMahon at Worth and Weissenburg, pushes him out of Alsace (NorthEastern France), surrounds Strasbourg, and drives on towards Nancy. The other two Prussian armies isolate Marshal Bazaine’s forces in Metz.

- August 16-18: French Commander Bazaine’s efforts to break his soldiers through the German lines are bloodily defeated at Mars-la-Tour and Gravelotte. The Prussians advance on Chalons.

- September 1: Battle of Sedan. MacMahon and Bonaparte, attempting to relieve Bazaine at Metz and finding the road closed, enters battle and is defeated at Sedan.

- September 2: Emperor Napoleon III and Marshal MacMahon capitulate at Sedan with over 83,000 soldiers.

- September 4: At news of Sedan, Paris workers invade the Palais Bourbon and force the Legislative Assembly to proclaim the fall of the Empire. By evening, the Third Republic is proclaimed at the Hotel de Ville (the City Hall) in Paris. The provisional Government of National Defence (GND) is established to continue the war effort to remove Germany from France.

- September 5: A series of meetings and demonstrations begin in London and other big cities, at which resolutions and petitions were passed demanding that the British Government immediately recognize the French Republic. The General Council of the First International took a direct part in the organization of this movement.

- September 6: GND issues statement: blames war on Imperial government, it now wants peace, but “not an inch of our soil, not a stone of our fortresses, will we cede.” With Prussia occupying Alsace-Lorraine, the war does not stop.

- September 19: Two German armies begin the long siege of Paris. Bismarck figures the “soft and decadent” French workers will quickly surrender. The GND sends a delegation to Tours, soon to be joined by Gambetta (who escapes from Paris in a balloon), to organize resistance in the provinces.

- October 27: French army, led by Bazaine with 140,000-180,000 men at Metz, surrenders.

- October 30: French National Guard defeated at Le Bourget.

- October 31: Upon the receipt of news that the Government of National Defense had decided to start negotiations with the Prussians, Paris workers and revolutionary sections of the National Guard rise up in revolt, led by Blanqui. They seize the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) and set up their revolutionary government–the Committee of Public Safety, headed by Blanqui. On October 31, Flourens prevents any members of the Government of National Defense from being shot, as had been demanded by one of the insurrectionists.

- November 1: Under pressure from the workers the Government of National Defense promises to resign and schedule national elections to the Commune–promises it has no intention to deliver. With the workers pacified by their ’legal’ charade, the government violently seizes the Hôtel de Ville and re-establishes its domination over the besieged city. Paris official Blanqui is arrested for treason.

1871

- January 22: The Paris proletariat and the National Guards hold a revolutionary demonstration, initiated by the Blanquists. They demand the overthrow of the government and the establishment of a Commune. By order of the Government of National Defense, the Breton Mobile Guard, which was defending the Hôtel de Ville, opens fire on the demonstrators. After massacring the unarmed workers, the government begins preparations to surrender Paris to the Germans.

- January 28: After four long months of workers struggle, Paris is surrendered to the Prussians. While all regular troops are disarmed, the National Guard is permitted to keep their arms–the populous of Paris remains armed and allows the occupying armies only a small section of the city.

- February 8: Elections held in France, unknown to most of the nation’s population.

- February 12: New National Assembly opens at Bordeaux; two-thirds of members are conservatives and wish the war to end.

- February 16: The Assembly elects Adolphe Thiers chief executive.

- February 26: The preliminary peace treaty between France and Germany signed at Versailles by Thiers and Jules Favre, on the one hand, and Bismarck, on the other. France surrenders Alsace and East Lorraine to Germany and promised to pay it indemnities to the sum of 5 billion francs. (SUPPRIMER: German army of occupation to slowly withdraw as indemnity payments made). The final peace treaty was signed in Frankfort-on-Main on May 10, 1871.

- March 1-3: After months of struggle and suffering, Paris workers react angrily to the entry of German troops in the city, and the ceaseless capitulation of the government. The National Guard defects and organizes a Central Committee.

- March 10: The National Assembly passes a law on the deferred payment of overdue bills; under this law the payment of debts on obligations concluded between August 13 and November 12, 1870 could be deferred. Thus, the law leads to the bankruptcy of many petty bourgeoisie.

- March 11: National Assembly adjourns. With trouble in Paris, it establishes its government at Versailles on March 20.

- March 18: Adolphe Thiers attempts to disarm Paris and sends French troops (regular army), but, through fraternization with Paris workers, they refuse to carry out thier orders. Generals Claude Martin Lecomte and Jacques Leonard Clement Thomas are killed by their own soldiers. Many troops peacefully withdraw, some remain in Paris. Thiers outraged, the Civil War begins.

- March 26: A municipal council–the Paris Commune–is elected by the citizens of Paris. Commune consists of workers, among them members of the First International and followers of Proudhon and Blanqui.

- March 28: The Central Committee of the National Guard, which up to then had carried on the government, resigns after it first decrees the permanent abolition of the “Morality Police”.

- March 30: The Commune abolishes conscription and the standing army; the National Guard, in which all citizens capable of bearing arms were to be enrolled, was to be the sole armed force. The Commune remitts all payments of rent for dwelling houses from October 1870 until April 1871. On the same day the foreigners elected to the Commune were confirmed in office, because “the flag of the Commune is the flag of the World Republic”.

- April 1: The Commune declares that the highest salary received by any member of the Commune does not exceed 6,000 francs

- April 2: In order to suppress the Paris Commune Thiers appeals to Bismarck for permission to supplement the Versailles Army with French prisoners of war, most of whom had been serving in the armies that surrendered at Sedan and Metz. In return for the 5 billion francs indemnity payment, Bismarck agrees. The French Army begins seige of Paris. Paris is continually bombarded and, moreover, by the very people who had stigmatized as a sacrilege the bombardment of the same city by the Prussians.

The Commune decrees the separation of the Church from the State, and the abolition of all state payments for religious purposes as well as the transformation of all Church property into national property. Religion is declared a purely private matter.

- April 5: Decree on hostages adopted by the Commune in an attempt to prevent Communards from being shot by the French Government. Under this decree, all persons found guilty of being in contact with the French Government were declared hostages. This was never carried out.

- April 6: The guillotine was brought out by the 137th battalion of the National guard, and publicly burnt, amid great popular rejoicing.

- April 7: On April 7, the French army captures the Seine crossing at Neuilly, on the western front of Paris.

Reacting to French government policy of shooting captured Communards, Commune issues an “eye-for-an-eye” policy statement, threatening retaliation. The bluff is quickly called; Paris workers execute no one.

- April 8: A decree excluding from the schools all religious symbols, pictures, dogmas, prayers–in a word, “all that belongs to the sphere of the individual’s conscience”–is ordered to be excluded from the schools. The decree is gradually applied.

- April 11: In an attack on southern Paris the French army is repulsed with heavy losses by General Eudes.

- April 12: The Commune decides that the Victory Column on the Place Vendôme, which had been cast from guns captured by Napoleon after the war of 1809, should be demolished as a symbol of chauvinism and incitement to national hatred. This decree was carried out on May 16.

- April 16: Commune announces the postponement of all debt obligations for three years and abolition of interest on them.

The Commune orders a statistical tabulation of factories which had been closed down by the manufacturers, and the working out of plans for the carrying on of these factories by workers formerly employed in them, who were to be organized in co-operative societies, and also plans for the organization of these co-operatives in one great union.

- April 20: The Commune abolishes night work for bakers, and also the workers’ registration cards, which since the Second Empire had been run as a monopoly by police nominees–exploiters of the first rank; the issuing of these registration cards was transferred to the mayors of the 20 arrondissements of Paris.

- April 23: Thiers breaks off the negotiations for the exchange, proposed by Commune, of the Archbishop of Paris [Georges Darboy] and a whole number of other priests held hostages in Paris, for only one man, Blanqui, who had twice been elected to the Commune but was a prisoner in Clairvaux.

- April 27: In sight of the impending municipal elections of April 30, Thiers enacted one of his great conciliation scenes. He exclaimed from the tribune of the Assembly: “There exists no conspiracy against the republic but that of Paris, which compels us to shed French blood. I repeat it again and again…”. Out of 700,000 municipal councillors, the united Legitimists, Orleanists, and Bonapartists ( Party of Order ) did not carry 8,000.

- April 30: The Commune orders the closing of the pawnshops, on the ground that they were a private exploitation of labor, and were in contradiction with the right of the workers to their instruments of labor and to credit.

- May 5: On May 5 it ordered the demolition of the Chapel of Atonement, which had been built in expiation of the execution of Louis XVI.

- May 9: Fort Issy, which is completely reduced to ruins by gunfire and constant French bombardement, is captured by the French army.

- May 10: The peace treaty concluded in February now signed, known as Treaty of Frankfurt. (Endorsed by National Assembly May 18.)

- May 16: The Vendôme Column is pulled down. The Vendôme Column was erected between 1806 and 1810 in Paris in honor of the victories of Napoleonic France; it was made out of the bronze captured from enemy guns and was crowned by a statue of Napoleon.

- May 21-28: Versailles troops enter Paris on May 21. The Prussians who held the northern and eastern forts allowed the Versailles troops to advance across the land north of the city, which was forbidden ground to them under the armistice–Paris workers held the flank with only weak forces. As a result of this, only a weak resistance was put up in the western half of Paris, in the luxury city; while it grew stronger and more tenacious the nearer the Versailles troops approached the eastern half, the working class city.

The French army spent eight days massacring workers, shooting civilians on sight. The operation was led by Marshal MacMahon, who would later become president of France. Tens of thousands of Communards and workers are summarily executed (as many as 30,000); 38,000 others imprisoned and 7,000 are forcibly deported.

A slightly adapted version of the timeline to be found at www.marxists.org

Translated by Snake Arbusto, Vicki Briault, Mike Krolikowski and Christine Pagnoulle

Notes:

- An historic insurrection in Paris that lasted just over two months, from 18 March 1871 to the “Bloody Week” from 21 to 28 May 1871. The French bourgeoisie had capitulated to the Prussian army that had reached the gates and tried to disarm the city by withdrawing the best part of its artillery. The people of Paris refused to capitulate and proclaimed the Commune, with the support of the National Guard. Radical social measures were taken, driven by the popular impulse. This was one of the first proletarian revolutions in history.

- The International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), known as the “First International”, denounced this aggression launched by the French Second Empire in a public appeal proclaimed on 23 July 1870, four days after the beginning of the hostilities. “Whatever may be the incidents of Louis Bonaparte’s war with Prussia, the death-knell of the Second Empire has already sounded at Paris. It will end, as it began, by a parody. But let us not forget that it is the governments and the ruling classes of Europe who enabled Louis Bonaparte to play during 18 years the ferocious farce of the Restored Empire.

On the German side, the war is a war of defence; but who put Germany to the necessity of defending herself? Who enabled Louis Bonaparte to wage war upon her? Prussia! It was Bismarck who conspired with that very same Louis Bonaparte for the purpose of crushing popular opposition at home, and annexing Germany to the Hohenzollern dynasty.” The IWA urged its members to adopt an Internationalist standpoint. The same declaration said “If the German working class allows the present war to lose its strictly defensive character and to degenerate into a war against the French people, victory or defeat will prove alike disastrous.” The IWA quoted a declaration that had been read before a big meeting in Germany: “In the name of German Democracy, and especially of the workmen forming the Democratic Socialist Party, we declare the present war to be exclusively dynastic…. We are happy to grasp the fraternal hand stretched out to us by the workmen of France….Mindful of the watchword of the International Working Men’s Association: Proletarians of all countries, unite, we shall never forget that the workmen of all countries are our friends and the despots of all countries our enemies.” This 23 July declaration was written by Karl Marx.

As indicated, the IWA brought together numerous activist organizations of diverse tendencies including Anarchists (behind Proudhon, Bakounine and others) and Socialist-Communist tendencies (among whom were Marx and Engels who did not want to be called “Marxist”). The IWA was constantly accused by established governments of being international revolutionary conspirators. Many prosecutions were instigated against IWA members throughout the 1860s.

The quotes taken from The First Address July 23, 1870 declaration are to be found in Karl Marx’s The Civil War in France (1871) They may be found here; www.marxists.org - In a text adopted on 9 September 1870 the IWA declared of the fall of the Second Empire: “… we hail the advent of the republic in France, but at the same time we labour under misgivings which we hope will prove groundless. That republic has not subverted the throne, but only taken its place, become vacant. It has been proclaimed, not as a social conquest, but as a national measure of defence. It is in the hands of a Provisional Government composed partly of notorious Orleanists, partly of middle class republicans (…)” in Karl Marx, The Civil War in France (1871), “The Second Address September 9, 1870”. In 1921, the fiftieth anniversary of the Paris Commune, Leon Trotsky expressed regret that the proletariat had not seized power in September 1870 but had let the bourgeoisie continue to rule. He wrote in Lessons of the Paris Commune (February 1921): “The Commune came too late. It had all the possibilities of taking the power on September 4 and that would have permitted the proletariat of Paris to place itself at a single stroke at the head of the workers of the country in their struggle against all the forces of the past, against Bismarck as well as against Thiers.” www.marxists.org

- NB The quotes from the Address of the General Council of the International Workingmen’s Association are taken from Karl Marx, The Civil War in France. “The Third Address, May 1871. [France capitulates and the government of Thiers].” There are several versions available on the Internet. Here we have used www.marxists.org Accessed 8 February 2021.

- To satisfy the demands of the bourgeoisie, Thiers’s government of and the Assembly dominated by conservative sectors favourable to the Prussian occupation had decided at the beginning of 1871 to end the moratorium on private debts, negotiable instruments and rents that crushed and squeezed the destitute Parisian population.

- In the document addressed to workers all over the world the leadership of the First International writes about this strategic mistake of 18 March: the Central Committee made themselves, this time, guilty of a decisive mistake in not at once marching upon Versailles, then completely helpless, and thus putting an end to the conspiracies of Thiers and his Rurals. In Marx, The Civil War in France, “The Third Address, May 1871. [Paris Workers’ Revolution & Thiers’ Reactionary Massacres].” www.marxists.org

- In Marx, The Civil War in France, “The Third Address, May 1871. [The Fall of Paris].” www.marxists.or

- Here you will find the decrees concerning rents and pawn-shops: macommunedeparis,”Non, la Commune n’a pas… (16) Premiers décrets–La Commune de Paris”, macommunedeparis.com (in French only).

- Pawn-brokers, or Monts-de-piété in French, were private institutions with share-holders who made a lot of profit. In 1869, they made 784 736, 53 francs. The annual turn-over was 25 million francs. There were about 40 branches in Paris. How it functioned: you handed over your item, known as a pawn or pledge, in exchange for a loan of 3 or 4 francs. You could redeem your pawn by paying interest of 12 to 15 %. If you did not redeem it within the agreed time, your item would simply be sold to the highest bidder. (English version adapted from: “The Commune et le Mont-de-piete” (The Commune and Pawn-brokers), (macommunedeparis.com)

- In a way, pawn-brokers foreshadow the private microcredit organizations that have appeared in developing countries over the last quarter of the 20th century.

- Source: “The Commune et le Mont-de-piete” macommunedeparis.com (in French only).

- See the book by Jean Baptiste Clément, La Revanche des communeux, Paris, 1887. It is a mine of information, particularly on the situation of the working classes and on the debates that took place in The Commune. The book is accessible online fr.wikisource.org (in French)

- 3 For a more complete list of social measures see the 1891 Introduction by Frederick Engels to Marx’s book, The Civil War in France, (1871), [Historical Background and Overview of the Civil War].” www.marxists.org See Appendix 2 of this article

- Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, Histoire de la Commune de 1871, Paris, 1896, republished by La Découverte / Poche, 2000. 576 pages. Accessible online in original French version gallica.bnf.fr

- Georges Beisson, “La Commune et la Banque de France”, Association of the friends of the Paris Commune de 1871 www.commune1871.org (in French only).

- Letter of 22 February 1881 from Karl Marx to Domela Nieuwenhuis, www.marxists.org

- Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, op. cit.

- See the 1891 Introduction by Frederick Engels to Marx’s book, The Civil War in France, (1871), [Postscript].” www.marxists.org

- The big Parisian private bankers at the head of the Bank of France celebrated the defeat of the Commune by distributing a dividend of 300 francs per share, much more than the 80 francs dividend paid out in 1870.

- Maxime Du Camp, La Banque de France pendant la commune,–III.–Les dernières réquisitions, l’ensablement des caves. Revue des Deux Mondes, 3e période, tome 27, 1878 (p. 831-865)

- Source: maitron.fr notice Charles Victor BESLAY, version published online 16 July 2013, last modified 28 January 2020 (in French).

- Beslay had founded a steam engine factory in the Popincourt district of Paris where he tried to apply his friend Proudhon’s ideas on the association of capital and labour. In particular, he associated his workers with the profits of his company in the 1848 exercise. During the Second Empire, he ruined himself by creating a bank of exchange and discount, again according to Proudhon’s ideas, which only functioned for six months. In 1852, he obtained the concession for two Swiss railway lines: the West-Swiss and the Franco-Swiss (See: en.wikipedia.org). In the already quoted IWA address, Marx writes about Beslay: “One of his former colleagues of the Chamber of Deputies of 1830, himself a capitalist and, nevertheless, a devoted member of the Paris Commune, M. Beslay, lately addressed Thiers thus in a public placard: ’The enslavement of labour by capital has always been the cornerstone of your policy, and from the very day you saw the Republic of Labor installed at the Hotel de Ville, you have never ceased to cry out to France: “These are criminals!”’”. (The author, Éric Toussaint, underlines.) In Marx, The Civil War in France, (1871), www.marxists.org

- Lissagaray, op. cit. History of the Paris Commune of 1871, Translated from the French by Eleanor Marx, at www.marxists.org

- Georges Beisson, La Commune et la Banque de France, Association of the friends of the Paris Commune de 1871 www.commune1871.org (in French).

- Maxime du Camp, La Banque de France pendant la commune, op. cit. (Trans. CADTM).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Proudhon’s supporters in the Commune were generally members of the IWA, which brought together men and women of diverse tendencies ranging from different currents of anarchism (Proudhonist, Bakouninist) to a plurality of Communist movements. Some Auguste Blanqui supporters such as Emile Duval were members of the IWA.

- For more about Charles Longuet see: maitron.fr (in French) and en.wikipedia.org

- Eric Toussaint, “Russia: Origin and consequences of the debt repudiation of February 10, 1918” www.cadtm.org

- See Eric Toussaint, Fernando Martinez Heredia, Du 19e au 21e siècle : une mise en perspective historique de la Révolution cubaine (19th and 21st centuries: A Historical perspective of the Cuban revolution) www.cadtm.org (in French or Spanish).

- See Eva Betavatzi, Éric Toussaint and Olivier Bonfond, The DiEM25 Plan to Confront the COVID-19 Crisis in Europe, 26 May 2020, www.cadtm.org

- See www.ecb.europa.eu

- See en.wikipedia.org