The Labor Department reported that the economy created just 18,000 jobs in June. It also revised down the previous two months’ numbers, bringing the average rate of job growth over this period to 87,000 jobs a month. The slow job growth led to another rise in the unemployment rate, which edged up to 9.2 percent. The employment-to-population (EPOP) ratio fell to 58.2 percent, the low hit in December of 2009 and again in November in 2010. This means that the job growth thus far in the recovery has been just sufficient to keep pace with the growth of the labor force.

The decline in EPOPs hit most groups, but black women saw the sharpest falloff, with their EPOP declining by 0.9 percentage points to 52.8 percent, another new low for the downturn. The EPOP for black women is 7.8 percentage points below the pre-recession peak in 2007. The EPOP for blacks overall edged down by 0.1 percentage points to 51.1 percent, also a new low for the downturn.

By education level, those with some college appear to be the big losers at the moment. Their unemployment rate rose by 0.4 percentage points to 8.4 percent, while their EPOP fell by 0.2 percentage points to 63.9 percent, the latter being a new low for the downturn. This may be the result of unemployed workers getting additional education and then still being unable to find work.

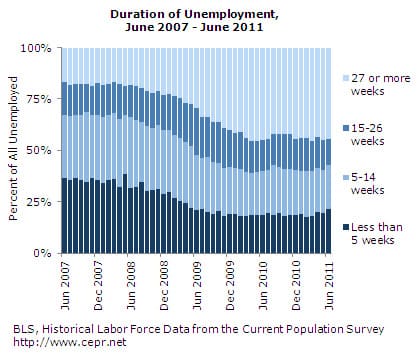

The median and average duration of unemployment both rose in June, with the latter reaching a record high of 39.9 weeks. This corresponded to an increase of 89,000 in the number of workers who had been unemployed for more than 26 weeks. While the share of the long-term unemployed fell slightly due to a jump in newly unemployed workers, it has been creeping up again in the last half year after declining in the fall of 2010. This should be a major policy concern since the long-term unemployed tend to have great difficulty finding new employment.

What is most striking in the establishment survey is that there are no sectors showing robust growth. Government was the biggest loser, shedding 39,000 jobs in June. Local government education accounted for the largest portion of this decline, losing 12,600 jobs, although this may reflect seasonal factors. Since peaking in August of 2008, state and local governments have shed 577,000 jobs.

Manufacturing employment increased by just 6,000 after shrinking by 2,000 in May. There is somewhat of a split with durable manufacturing adding an average of 16,000 jobs over the last three months, while non-durable manufacturing shed 5,000 per month. The construction sector is still shrinking with a loss of 9,000 jobs.

Retail added 5,200 jobs, barely offsetting a decline of 4,300 in June. Financial services shed 15,000 jobs, more than offsetting a gain of 14,000 in June. Recent layoff announcements suggest that this decline is likely to continue. Growth in health care employment appears to be slowing, averaging just 16,000 over the last two months compared with an average of 24,000 over the last year. Even restaurant employment has slowed, adding just 9,000 jobs after being flat in May.

Furthermore, there is no evidence in this report of any momentum for a turnaround. Jobs in employment services (temp help) fell by 9,500, the third consecutive decline. Average weekly hours edged down by 0.1 hour to 34.3. Hours in manufacturing fell by 0.3 hours. The average hourly wage fell slightly in June and has risen at just a 1.7 percent annual rate over the last three months. With wages not keeping pace with inflation and hours falling, workers’ purchasing power and consumption are likely to lag.

On the whole, this is one of the most negative employment reports since the recovery began. It indicates that the economy has made no progress whatsoever in re-employing the people who lost their jobs in the downturn. Even more discouraging is the fact that there is no reason to expect anything to change for the better any time soon. The pace of job loss in the public sector is likely to accelerate, with no evidence of an offsetting pickup in the private sector.

Dean Baker is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books, including False Profits: Recovering from the Bubble Economy. This article was first published by CEPR on 8 July 2011 under a Creative Commons license.

| Print