The recent “burqa bans” in Austria and Quebec appear to be troubling legal manifestations of the rising tide of Islamaphobia in Europe and North America. The news coverage of the bans coincided for me with a bout of reflexive angst regarding the recent publication of an article on Shari’a based reservations to CEDAW. I wrote the article years ago while working in women’s rights as a non-Muslim in Egypt and having to struggle with problems of the intersection of international law and religion. The desire to further crystallize assumptions behind my approach and articulate the politics of my position prompted this reflection.

My feminist approach aims at the perpetually shifting mark of solidarity with women across borders and in very different social and economic situations. A quixotic approach, at the junction of Islam and women’s rights, it requires supporting Muslim women who want to practice their religion in a way meaningful for them as well as solidarity with women in Muslim-majority countries or communities who want to live secular or less religiously constrained lives. Avoiding facile solutions means inhabiting a small space of resistance in which fear of being Islamaphobic cannot lead to excusing women’s oppression, while the quest for women’s empowerment cannot buttress Islamaphobia or familiar colonial tactics that may worsen concrete situations for some women.

I propose seven considerations not only on the burqa ban, but also on the larger question of engaging in women’s rights internationally. This critical approach is theoretically eclectic and consciously reflexive. While not necessarily original, these points may perhaps be useful when trying to navigate the complicated problems that arise from the intersection of international law, women’s rights and religion.

1.

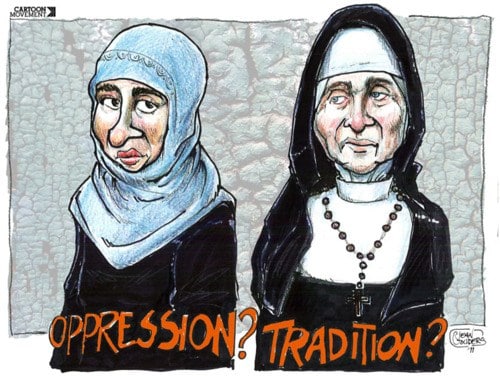

We cannot misconstrue women’s oppression as a phenomenon of any particular culture. Patriarchy remains a formidable force worldwide. Despite the different forms, social contexts or religious expressions they take, the exploitation and the oppression of women persist. We should be skeptical of any political or women’s rights agenda that singles out Islamic forms of oppression while overlooking other religious practices as private acts and “personal choice.” When women are forced to wear the niqab, it destroys the semblance of agency based on the objectification of women. However, is it the same if women choose to wear the niqab? Are women in insular Christian or Jewish communities who observe obligations to dress modestly or “femininely” treated differently from Muslim women? Questions of choice and religion are fraught within a global feminist legal framework partly because it is difficult to consider context while using general, universalizable rules. If we are troubled by women’s objectification rather than their choice to be or not be objectified, then we need to assess familiar practices with the same critical eye as “exotic” forms. Agency must matter, but if we champion choice alone, we risk legitimating patriarchal and oppressive practices. We need an eclectic feminist lens that allows us to examine choice and objectification, and to see fluidity and structure.

2.

We must recognize the complexity of agency and choice across socio-demographics and states. As it still stands, white women in the global North are often perceived to make choices while religious and racialized women are acted upon. We must view constraint and ideology in the way women’s choices are formed even when they are economically privileged, white or from the global North, and recognize agency in women when they are in vulnerable positions, religious, of color, or from the global South. Recovering some of the insights and language of radical feminists problematizes dominant conceptions of choice. Being radical with a postcolonial, critical-race approach means we should scrutinize patterns of whose agency matters to reduce harm to historically marginalized populations without ignoring structural oppression.

3.

We must appreciate women’s differing desires while at the same time recognize those desires as partly formed by social, economic and religious forces. The niqab bans are often suspicious because they are sponsored by and aligned with far right ideologies. However, would we feel differently if it were not just a handful of women but a large percentage wearing the niqab, or if other women in the same community expressing social pressure to wear it then sponsored the bill? Finding legal structures that support choice and simultaneously push back against patriarchal ideologies requires a feminist agenda that does not shy away from radical insights on ideology but still remains grounded in a rights-based approach. We cannot look superficially at social phenomena but address these issues in context elevating the voices and arguments of women most affected. While at the same time we must be willing to challenge patriarchy inside religious structures, whether state-based or purely “private.” This approach requires community-based dialogue since the mode of challenging patriarchy matters.

4.

We shouldn’t fetishize the niqab or the veil. This is a standard line, but worth repeating. I mean this in the sense that to veil or not to veil is one question among many that women face in Muslim communities. But it somehow eclipses other questions about women’s liberation because it is visible. These laws displace the harder questions about women’s power in public life and activities. We must be concerned with the conditions of women’s lives rather than focusing on the most visible signs of Islamic difference. There are good reasons to believe that denying services to women wearing the niqab in Quebec or fining women in the niqab in Austria target and will isolate the women who wear it. However, of course we should still be concerned about ideologies that promote ideas and practices that limit women’s roles in public life or assert a uniquely female requirement of modesty. Ideologies cannot go unchallenged, but the question remains whether or not they should be criminalized. Anything that limits the kinds of activities women can engage in should face heightened scrutiny and cannot be protected by state interests on the one hand nor personal “choice” on the other. The state using the blunt force of a ban or fine against women is a particularly coercive means to ensure equality. There are more effective ways to combat patriarchal ideology that do not target women.

5.

We need to radicalize women’s rights as an economic issue. The world is moving away from conditions that favor women’s empowerment across the board. Although women’s oppression cannot and should not be reduced entirely to economics, materialist feminist theories have been marginalized. Meanwhile, security agendas are moving to adopt a women and economic development strategy to combat religious extremism. The gap in consciously leftwing feminist theory has been filled by a woman’s agenda that promotes female empowerment particularly in the global South as market expansion. The position that women’s interests and market interests are necessarily symbiotic instrumentalizes women to fit the needs of the market. The chipping away of the welfare state in the global North and the pressures to liberalize economies in the global South mean that the basic conditions for women’s empowerment are being broadly challenged. Feminism must grapple with the labor conditions of advanced capitalism and its real impacts on women. The idea that access to the formal market will give women choices fails to see how the market constrains choice as well. As feminists fought for access to the labor force, a new generation is asking if feminism merely opened doors for women to aspire to equal oppression with men.

6.

Economic systems are not gender neutral. Different women face different challenges as their gender intersects with race, disability, class and having children. Not all women are mothers, nor should they have to be. But motherhood remains a repressed obstacle for women’s equality and empowerment especially in the intersection with class. When women opt out of motherhood or opt out of an oppressive labor market because of the impossibility of work-life balance, it is difficult to say it is by “choice” alone. Parenting is not a condition that “temporary special measures” are necessarily well equipped to deal with. We do a disservice to women when we pretend that “leaning in” or being “women who work” is an option for more than the most privileged persons in society. The reality for most women is that if they are not wealthy, or have a family member or partner who can care for children, or have high quality state-funded child-care that extends to the hours women now work, there are not a lot of “choices.” When women give birth and if they nurse, they are connected to another human in a way that is simply different from the way most men experience parenthood. This is why women must have control over their reproductive lives. Physical difference cannot be used as an argument to limit women’s choices, but repressing the phenomenological experience of many mothers has clear costs. Too many “choices” women make in formally equal societies are left unexamined. The legal structure of a robust welfare state that supports women is seen as a political “choice” as opposed to a necessary condition for women’s equality. We need a feminist agenda that looks at how choice is constructed on structural and economic levels.

7.

We must recognize how law can be used coercively against marginalized groups, the limitations of law for radical social change, and the costs of disengaging with law. The moment human rights became a system of law they became (among other things) a coercive force of the state. Human rights treaties are treaties among states, and, according to the United Nations’ International Law Commission at least, not a special area of law. There are limits to the structure of international law and consequently human rights. Should we abandon human rights for this reason? Can we afford to? We have different answers to this at different moments, but one thing is clear: reactionaries and the far right are not stepping away from state power or from legal transformation. If we engage in legal reform, we should not fail to see the structure of international law for our advocacy strategies or for supporting women’s groups around the world. We inhabit the political, economic system we are in but that does not mean giving up on aspirational projects. We should push the system to its absolute ends and break open new possibilities, but always cognizant of the challenges women face in the present.

Related articles for further reading

- Burqa Ban (Aljazeera)

- Gender Justice In Europe

- Islamophobia app on college campuses

- Anti-sharia bills in U.S.

- Women entrepreneurs help fight extremism

- Erosion of welfare state (ex. Finland)

- Grow the economy and help women

Tanya Monforte is a DCL candidate at McGill Law School and an O’Brien Graduate Fellow at the Center for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism. Prior to moving to Montreal she directed a Human Rights Master’s Program at the American University in Cairo where she taught law. She holds a J.D. from Harvard Law School. She also holds a B.A. in philosophy as well as an M.A. in the sociology of law. She writes on issues of human rights and critical security studies and is currently writing on civil death and global security.