In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” The first five posts (here, here, here, here, and here) will serve as the basis for chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today. The text of this post is for Chapter 2, Marxian Economics Versus Mainstream Economics (a short addendum to a previous post on Economic Theories and Systems).

The relation between economic theories and economic systems is even more dynamic. The various economic theories of capitalism are not just different ways of making sense of that particular economic system. They emerge, develop, and change over time as capitalism itself changes—and, in turn, they have effects back on capitalism.

The history of economic thought shows that both mainstream economics and the Marxian critique of mainstream economics first appeared—and then grew or declined in influence, were debated and questioned, gave rise to new concepts and methods, and so on—as capitalism first came into existence and then changed over time. Thus, for example, after the crash of 2007-08, mainstream economics was widely questioned: because its theories and policies, in part, created the conditions that led to the crash; because it failed to include even the possibility of such a crash in its models; and because, once the crash occurred, it had little to offer in the way of effect remedies.

At the same, there was a resurgence of interest in theories that presented criticisms of mainstream economic theory and capitalism, including Marxian economics. Many people, inside and outside the academy, went back to ideas, including those associated with the Marxian critique of political economy, to make sense of what was going on. Precisely because they didn’t find answers to such pressing questions as capitalist instability, the role of finance, growing inequality between the top 1 percent and everyone else, a wide variety of professors, students, activists, and pundits questioned the theories and policies of mainstream economics and expressed renewed interest in Marxian and other non-mainstream approaches to economics that had been sidelined or ignored in recent years.

But the relation between economic theories and economic systems doesn’t go in only one direction. The ideas of different schools of thought within economics also have an impact on the economic systems they’re designed to analyze. This is what is often called the “performativity” of economics. The ideas that are produced by professional economists (as well as noneconomists, inside and outside the academy) often lead to changes in capitalism itself.

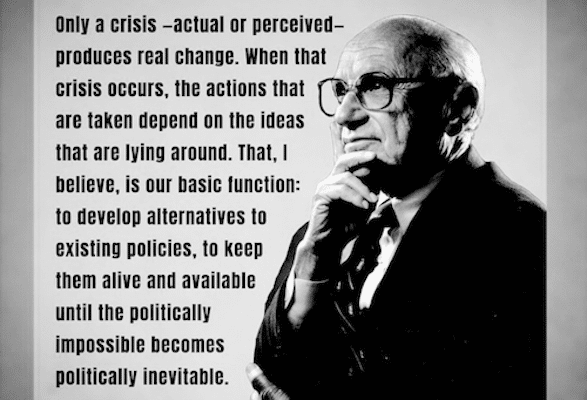

This is particularly true, as neoclassical economist Milton Friedman famously wrote, in times of crisis.

Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable. (Capitalism and Freedom, xiv)

Economic theories are not just out there, as a matter of academic curiosity and endeavor (or, sometimes for students, a necessary evil to be learned and recited on an exam). They often lead to changes in capitalism, especially if they influence the way people think about their role in capitalism and attract the attention of influential economic and social groups who run capitalism’s key institutions.

In fact, economic theories are designed to do exactly that. When, for example, mainstream economists argue that free markets are the best solution to various economic and social problems—whether budget deficits or poverty or unemployment—they are saying that the world should have more of such markets. And, when changes are made to introduce more markets, mainstream economics has performed its role.

The Marxian critique of mainstream economics also has that performative dimension—with one key difference: whereas mainstream economists want to create a world of which their theory is a better representation, Marxian economists want to do exactly the opposite. They want to contribute to the project of eliminating capitalism, and when that happens, Marxian economics will no longer have a reason to exist.

The performativity of the Marxian critique of political economy is precisely to be its own grave-digger.