In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” The first five posts (here, here, here, here, and here) will serve as the basis for chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today. The text of this post is for Chapter 2, Marxian Economics Versus Mainstream Economics (following on from the previous posts, here, here, here, and here).

Limits of Mainstream Economics Today

Keynes’s criticisms of neoclassical economics set off a wide-ranging debate that came to define the terms of—and, ultimately, the limits of debate within—mainstream economics.

On one side are neoclassical economists, who celebrate the invisible hand and argue that markets are the best way to efficiently allocate scarce resources. On the other side are Keynesian economists, who argue instead for the visible hand of government intervention to move markets toward full employment.

That tension, between the theories and policies of neoclassical and Keynesian economics, is the reason why in most colleges and universities the principles of economics are taught in two separate courses: microeconomics and macroeconomics. Moreover, the tension between the two schools of thought plays out within every area of economics, including (but certainly not limited to) microeconomics and macroeconomics.

One way of understanding the differences between the two approaches is to think about them as conservative and liberal interpretations of mainstream economics. Conservative mainstream economics tend to presume that the basic assumptions of neoclassical economics hold in contemporary capitalism, while liberal mainstream economists think they don’t.

Let’s consider two examples. First, within microeconomics, conservative mainstream economists (such as the late Milton Friedman) believe that individuals make rational decisions within perfectly competitive markets. Therefore, if markets exist, they should be allowed to operate within any regulations; and, if a market doesn’t exist, it should be created. Liberal mainstream economics (such as Joseph Stiglitz), on the other hand, see both individual decisions and markets as being imperfect—because individuals have limited or asymmetric information, some firms have more market power than others, and so on. Therefore, they argue, markets need to be guided to the best outcome.

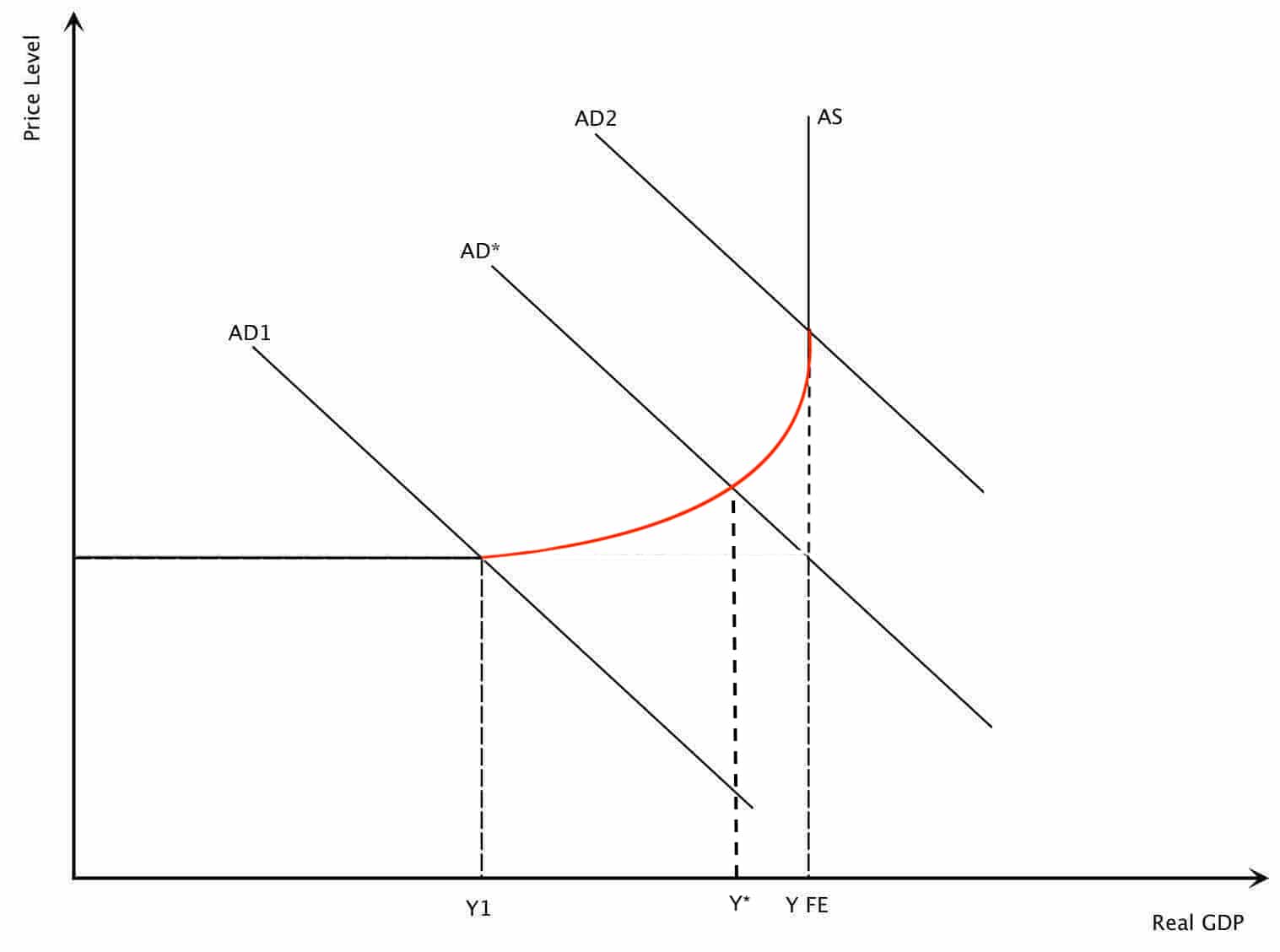

The second example is from macroeconomics. The view of conservative mainstream economists (such as Thomas J. Sargent) is that capitalism operates at or close to full employment (where, in the chart above, aggregate demand intersects the vertical portion of the aggregate supply curve), whereas liberal mainstream economists (such as Paul Krugman) believe that unregulated markets often lead to considerable unemployment (where aggregate demand intersects the horizontal portion of the aggregate supply curve, at level of output less than full employment).*

To attempt to reconcile the two competing views, many mainstream economists argue for a “middle position”—somewhere between the opposed neoclassical and Keynesian views. There (in the red portion of the aggregate supply curve), mainstream economists find a tradeoff between increases in output and changes in the price level, that is, between inflation and unemployment.

And the predominant view within mainstream economics shifts back and forth between the two poles. Sometimes, as in the years before the crash of 2007-08, mainstream economics moved closer to the neoclassical approach. That’s when policies such as deregulation, privatization, the reduction of government deficits, welfare reform, and so on were all the rage, within both academic and political circles. After the crash, when the neoclassical approach was said to have failed, mainstream economics swung back in other direction. That’s when there were calls for more government intervention and fewer worries about budget deficits and the like.

In the midst of the Pandemic Depression, much the same kind of debate between advocates of the two poles of mainstream economics has been taking place. On one side, conservative mainstream economists have argued in favor of rescuing banks and corporations, such that an economic recovery would “trickle down” to workers and their households. Liberal mainstream economists, on the other hand, have favored direct payments to working who were furloughed or laid off—an idea that was attacked by their conservative counterparts, because such payments were seen as providing a “disincentive” for workers to return to their jobs.

Every time capitalism enters into crisis, the same kind of debate breaks out between conservative and liberal economists (and, of course, between different groups of politicians and voters).

If mainstream economists are so divided between the two approaches, what in the end unites them into what I have been calling mainstream economics? Like all such labels, it is defined in part by what it includes, and in part by what it excludes.

What mainstream economics includes is the idea that neoclassical and Keynesian approaches establish the limits within which theoretical and policy debates can and should take place. Together, they define what is in the “economic toolkit,” and therefore what it means to “think like an economist.” Moreover, the two groups of economists argue that capitalist markets are the way a modern economy can and should be organized. They may disagree about the relevant approach—for example, the “invisible hand” of free markets versus the “visible hand” of government intervention. But they all agree on the goal: to create the appropriate institutional environment so that capitalist markets work properly.

They also share the view that the only way capitalism operates falls below its general equilibrium, full-employment potential is because of some external “shock.” In other words, all economic downturns, such as recessions and depressions, are due to external causes, not because of anything internal to the normal workings of capitalism.

What the definition of mainstream economics excludes is any approach, such as Marxian economics, that is based on a theoretical approach that lies outside the protocols of neoclassical and Keynesian economics. So, for example, the idea of class exploitation is generally overlooked or ignored within mainstream economics. Similarly, imagining and creating ways of allocating resources other than through capitalist markets are pushed to or beyond the margins by mainstream economists.

Together, the inclusions and exclusions contained within the definition of mainstream economics serve to define what mainstream economists think and do in their theoretical practice as well as in the policy advice they offer.

———

*As many contemporary Post Keynesian economists have noted, when neoclassical and Keynesian were combined in a single approach to economics (for example, in the “neoclassical synthesis” in the decades following World War II), many of the critical aspects of Keynes’s writings—including the notion of uncertainty and the idea that much stock market investment was merely speculation and added little to the productive capacity of the “real” economy—were downplayed or ignored altogether.