In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” The first five posts (here, here, here, here, and here) will serve as the basis for chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today. The text of this post is for Chapter 2, Marxian Economics Versus Mainstream Economics (following on from the previous posts, here, here, and here.)

Keynesian Economics

Once it was created as a new theory of capitalism, neoclassical economics expanded its influence—in its original countries as well as elsewhere.* Not surprisingly, it was also criticized, for example, by the so-called institutionalists (such as Thorstein Veblen, the author of The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions) and by economists who challenged various of its assumptions, including the presumption of perfect competition (especially at Cambridge University, in England, by the likes of Piero Sraffa and Joan Robinson).**

Within mainstream economics, the most far-reaching critique occurred during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when, against one of the main conclusions of neoclassical economists—that capitalism would aways tend toward full employment—millions of workers were thrown out of their jobs and the rate of unemployment soared to over 25 percent.

British economist John Maynard Keynes is the most famous of those critics. He challenged two major features of government policy at that time, measures that were consistent with neoclassical economics: first, that a decrease in wages would restore full employment, and, second, that government budget deficits should be avoided at all costs. Instead, Keynes argued, lowering wages would merely lead to less spending, and therefore more unemployment, and budget deficits during economic downturns were actually a good thing, as they were a way for governments to stimulate private spending in order to move capitalist economies back toward full employment.

In 1936, Keynes wrote and published his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, which provided the theoretical basis for his attacks on austerity measures and his alternative program of government deficit spending.

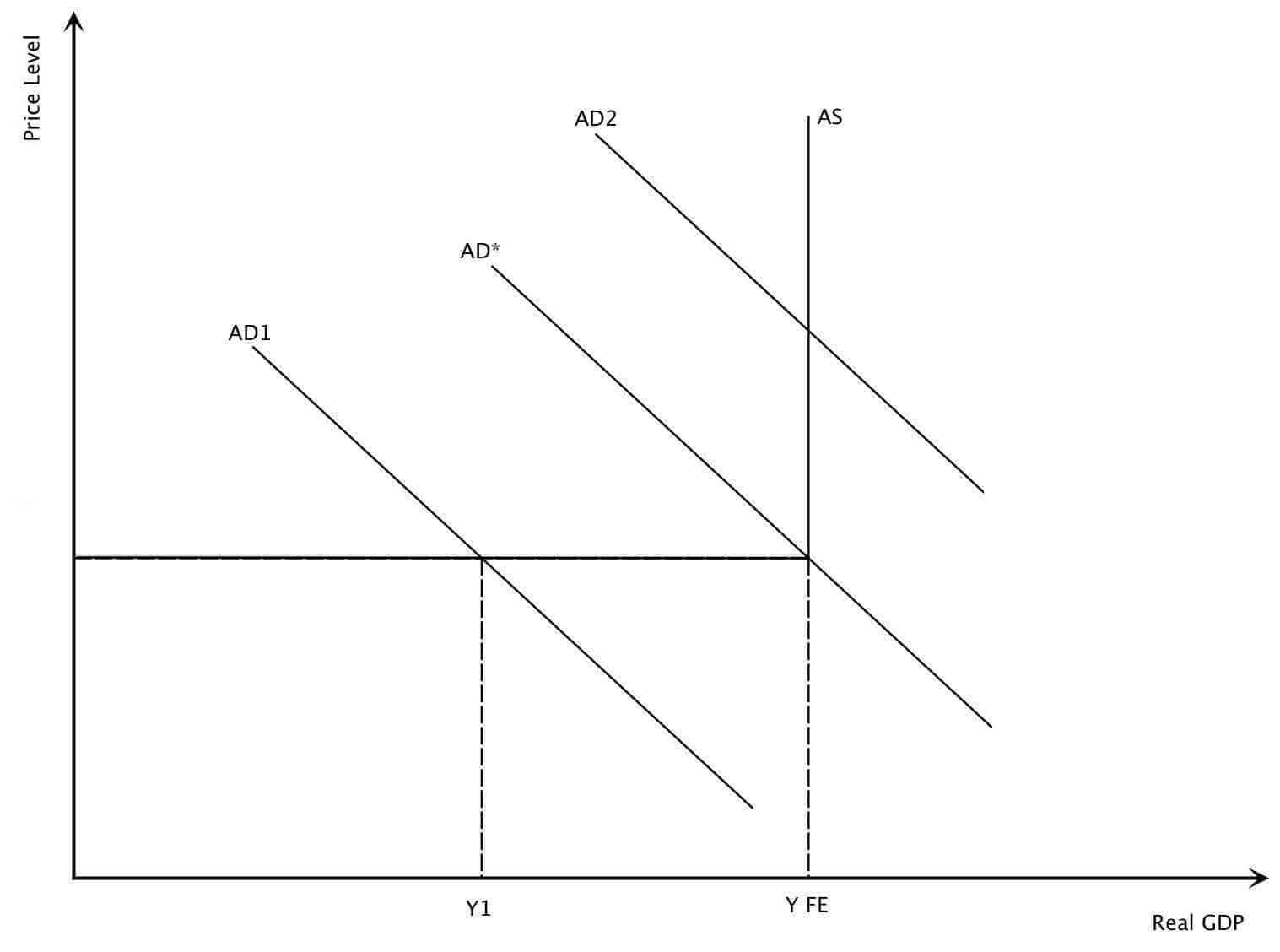

One way to see the impact of Keynes’s theoretical innovation is to use the contemporary model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand.*** Basically, neoclassical economists conclude that a capitalist economy will always be at full employment (at a level of output Y FE, where Y is inflation-adjusted national output, measured in terms of Gross Domestic Product, and FE is full employment) at the intersection of downward-sloping aggregate demand (AD*) and perfectly vertical aggregate supply (AS) curves. Therefore, any attempt to raise aggregate demand (e.g., to AD2), will only raise prices (an increase in the price level, on the vertical axis) and leave the level of output (and therefore employment) unchanged.****

Keynes, in contrast, argued that, during economic downturns, aggregate demand would decline (e.g., to AD1) and, with a perfectly elastic aggregate supply curve at less than full employment (the horizontal section of AS), output would fall to less than full employment (Y1). Moreover, there were no automatic mechanisms within capitalism to restore full employment. Without the visible hand of government intervention—for example, deficit spending—the economy would operate at a level of output below full employment. Finally, Keynes argued, aggregate demand could be increased without provoking inflation (again, a general increase in the price level), an idea that economists and politicians opposed to deficit spending argued then and continue to claim today.

How did Keynes arrive at conclusions that ran so much against the neoclassical grain? Keynes did not reject all aspects of neoclassical economics—especially its theory of income distribution or its celebration of capitalism. But he did criticize some key assumptions, especially the idea that capitalism should be analyzed starting from individual decisions based on utility-maximization and complete knowledge. Instead, Keynes placed a great deal of importance on mass psychology and the limits to knowledge or uncertainty.

Mass psychology and uncertainty are particularly important when it comes to capitalists’ investment decisions, which are an important component of aggregate demand. For Keynes, working-class households were expected to use for consumption a large and relatively stable share of their income (what is often referred to as the consumption function). Investors, however, engaged in a much more volatile set of decisions, and that’s because in many instances they had no rational knowledge about the future. They simply could not know.

So, given their uncertainty, how could capitalists make investment decisions? Much to the chagrin of other mainstream economists, then as now, Keynes argued in the General Theory that investors were guided by “animal spirits”—an urge to act that could not be understood in terms of quantitative benefits and probabilities.

So, if capitalists couldn’t make rational decisions, and were propelled instead by their “animal spirits,” what guide could they follow? Keynes turned to mass psychology, a kind of herd mentality, according to which capitalists looked at what everyone else was doing and followed suit—sometimes in a positive vein, other times in a negative direction.

That made investment demand, the other key component of aggregate demand, quite volatile—and could often (as during and after the stock market crash of 1929) initiate a downward spiral. Capitalists would stop investing, thereby decreasing production and destroying investor confidence, which would lead to even less investment and production, in a kind of capitalist freefall. Moreover, since private decisions in markets only worsened the initial downturn, there was no mechanism within capitalism to turn things around. The invisible hand failed.

That’s why Keynes argued—first in letters to government leaders, including Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and then in the General Theory—that the only thing that would save capitalism would be for the government to step in with aggressive fiscal policy (deficit spending) and an accommodating monetary policy (such as lowering interest rates), to raise aggregate demand (from AD1 back toward AD*, in the chart above). In other words, the solution Keynes proposed was the visible hand of government intervention.

———

*The second generation of neoclassical economists included the following: in England, Philip Wicksteed, Francis Edgeworth, and Alfred Marshall; in Switzerland, Vilfredo Pareto; and, in Austria, Eugen Böhm von Bawerk and Friedrich von Wieser. Neoclassical economics also found fertile ground in the United States, early on in the work of such economists as John Bates Clark, Fred M. Taylor, and Frank William Taussig. Later, especially after World War II, with the rise of U.S. hegemony, both economically and intellectually, neoclassical economics was spread throughout the world.

**Many contemporary readers, including students of economics, will not recognize the names of Veblen, Sraffa, and Robinson precisely because of the predominance of neoclassical economics.

***While Keynes introduced the concepts of aggregate supply and demand in chapter 3 of the General Theory, a model based on aggregate supply and demand as a way of representing and teaching mainstream macroeconomics wasn’t common until the 1990s. Today, it is ubiquitous. The problem is, in many principles and intermediate-level economics texts, aggregate supply/aggregate demand analysis has had the effect of misleading students into thinking that the analysis of the aggregate economy is essentially the equivalent to market equilibrium analysis. While we don’t need to go into detail here, the underpinnings of aggregate supply and aggregate demand have nothing to do with the way we market supply and demand are determined, such as in the section above on neoclassical economics.

****Therefore, the only way to raise output and employment in the neoclassical model is to increase (push out to the right) the vertical aggregate-supply curve. That can only happen if the exogenous determinants of aggregate supply change—for example, through an increase in labor, capital, and land or an improvement in technology.