In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” The first five posts (here, here, here, here, and here) will serve as the basis for chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today. The text of this post is for Chapter 2, Marxian Economics Versus Mainstream Economics (following on from the previous posts, here, here, here, here, and here).

Classical Political Economy

Marxian economists have been quite critical of contemporary mainstream economics. As we saw in Chapter 1, and will continue to explore in the remainder of this book, Marxian economists have challenged the general approach as well as all of the major conclusions of both neoclassical and Keynesian economics.

But what about Marx, who wrote his critique of political economy, let’s remember, before neoclassical and Keynesian economics even existed?

Marx, writing in the middle of the nineteenth century, trained his critical eye on the mainstream economic theory of his day. He read Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, as well as the writings of other classical political economists, such as Thomas Robert Malthus, Jean-Baptiste Say, and John Stuart Mill.

Marx’s critique of political economy can rightly be seen as both an extension of and break from the work of those late-eighteenth-century and early-nineteen-century mainstream economists. So, in order to understand why and how Marx proceeded in the way he did, we need to have a basic understanding of classical political economy.

Before we begin, however, we have to recognize that Marx’s interpretation of the classical economists was very different from the way they are referred to within contemporary mainstream economics. Today, within non-Marxian economics, the classicals are reduced to a few summary ideas. They include the following: a labor theory of value (which mainstream economists reject, in favor of utility), the invisible hand (which, as it turns out, Smith mentioned only three times in his writings, once in the Wealth of Nations), and comparative advantage (but not the rest of Ricardo’s theory, especially his theory of conflict over the distribution of income).

We therefore need a good bit more in order to make sense of Marx’s critique of political economy.

Adam Smith

Let’s start with Adam Smith, the so-called father of modern economics. The author of, first, the Theory of Moral Sentiments and, then, the Wealth of Nations, Smith asserted that people have a natural “propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” In other words, according to Smith, the ability and willingness to participate in markets were natural, and not social and historical, aspects of all humanity.

That’s not unlike contemporary mainstream economists’ insistence on presuming the existence of markets, and thus writing down supply and demand functions (or drawing them on a graph), without any further evidence or argumentation. They’re presumed to be natural.

Smith then proceeds by showing that the division of labor (such as with his most famous example, of the pin factory) has two effects: First, it leads to increases in productivity, and therefore an increase in production. Second, the extension of the division of labor within factories propels a division of labor within capitalism as a whole, as firms specialize in the production of some goods, which they can then trade with other producers in markets. In turn, the expansion of markets leads to more division of labor and higher productivity, thus increasing the wealth of nations.

Again, the parallel with contemporary mainstream economics is quite evident, which is recognized in the “classical” portion of the name for neoclassical economic theory. Using Gross Domestic Product as their measure of the wealth of nations, contemporary mainstream economists celebrate capitalism because higher productivity results in more output, which is then traded on markets. This is the basis of contemporary mainstream economists’ definition of development as an increase in GDP per capita, that is, more output per person in the population.

However, unlike contemporary mainstream economists, Smith analyzed the value of commodities in terms of the amount of labor it took to produce them. With increasing productivity, more goods and services could be produced and sold in markets, each containing less labor—and therefore available at lower prices to consumers. The nation’s wealth would therefore grow, especially as the number of workers grew.

Still, Smith worried about whether capitalist growth would persist in an uninterrupted fashion. The division of a nation’s production into “natural” rates of wages, profits, and rent to workers, capitalists, and landlords was not sufficient. What if, Smith asked, a large portion of capitalists’ profits was used to hire more “unproductive” labor, that is, the labor of household servants and others that did not contribute to increasing productivity? Purchasing labor involved in what we now call conspicuous consumption represented, for Smith, a slowing of the accumulation of additional capital. Therefore, it created a problem, an obstacle to future capitalist growth.

David Ricardo

David Ricardo picked up where Smith left off. He extended the celebration of capitalist markets to international trade. His argument was that if nations specialized in the production of commodities for which they had a relative advantage, and traded them for goods from other countries (his most famous example was British cloth and Portuguese wine), both countries would benefit. Their wealth would increase.*

That’s the only reason Ricardo’s work is cited by contemporary mainstream economists. However ironically, they ignore the fact that Ricardo made his argument based on the labor theory of value—just as they never mention Ricardo’s concern that conflicts over the distribution of income might slow capitalist growth.

In particular, Ricardo was worried that, as capitalism developed, the profits received by capitalists would be squeezed from two directions: an increase in workers’ wages and a rise in rent payments to landlords. Lower profits would mean less capital accumulation and slower growth—and, in the limit, capitalism would grind to a halt.

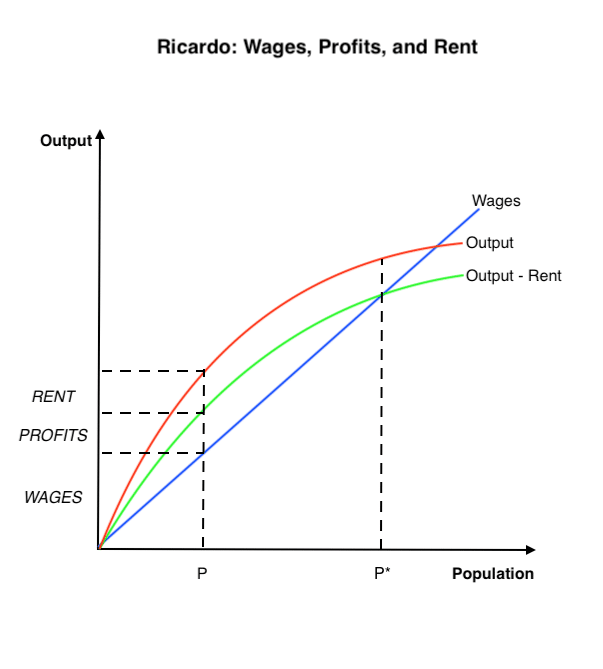

We can see how this might happen in the chart above. At a certain point (a level of population P, which is the pool of workers), total output (the red line) would be divided into workers’ wages, capitalists’ profits, and landlords’ rent).

It is easy to see that, at any point in time, if the wage rate paid to workers increased (which would mean an increase in the slope of the blue line), that would cut into profits (the vertical distance between the blue and green lines would decrease). That’s the major reason Ricardo supported free trade (and thus a repeal of the so-called Corn Laws): so that cheaper wheat could be imported from abroad, thus lessening the upward pressure on workers’ wage demands.

Even if the rate paid to workers remained the same over time (and thus the total amount of wages rose at a constant rate, with an increase in population), capitalists’ profits would be squeezed from the other direction, by an increase in the rents paid to the class of landlords (the vertical distance between the green and red lines). Basically, as agriculture production was moved to less and less fertile land, the rents on more productive land would rise, siphoning off a larger and larger portion of profits.

At a certain point (e.g., at a level of population P*), the entire output would be divided between workers’ wages and landlords’ rent, and nothing would be left in the form of capitalists’ profits. As a result, capitalists would be forced to stop investing and capitalist growth would cease.

Other Classicals

The Reverend Thomas Malthus was, if anything, more pessimistic than Ricardo. But he foresaw capitalism’s problems coming from the other direction, from the working masses. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, he argued that population would likely grow faster than the expansion in food production, especially in times of plenty. With such an increase in the supply of workers and a rise in the price of available food, workers’ real wages would inevitably fall and poverty would rise. The only solution was for capitalists and landlords to hire all the additional labor, and for workers’ wages to be restored to their “natural” level.

If Malthus focused on the up-and-down cycles of population and wages, and both Smith and Ricardo the potential limits to capitalist growth, the French classical economist Jean-Baptiste Say emphasized the inherent stability of capitalism. Why? Say’s argument was that the production of commodities causes income to be paid to suppliers of the capital, labor, and land used in producing these goods and services. And because the sale price of those commodities was the sum of the payments of wages, rents, and profit, income generated during production of commodities would be used to purchase all the commodities produced. Moreover, entrepreneurs were rewarded for correctly assessing the needs reflected in markets and the means to satisfy those needs. The result is what was later coined as Say’s Law: “supply creates its own demand.”

Finally, it was John Stuart Mill who added utilitarianism to classical political economy. Extending the work of Jeremy Bentham, especially the “greatest-happiness principle” (which holds that one must always act so as to produce the greatest aggregate happiness among all sentient beings), Mill argued that the greatest happiness and the least pain could be achieved on the basis of free markets, competition, and private property—with the proviso that everyone should be afforded an equal opportunity, however unequal the actual results might turn out to be. In particular, Mill defended the profits of capitalists as a just recompense for their savings, risk, and economic supervision.*

Marx’s Critique of Mainstream Economics

That, in a nutshell, is the mainstream economic theory Marx confronted while sitting in the British Museum in the middle of the nineteenth century. Marx both lauded the classical political economists for their efforts—especially Ricardo, who in his view “gave to classical political economy its final shape” (Critique of Political Economy)—and engaged in a “ruthless criticism” of their theory.

In this sense, Marx took the classical political economists quite seriously. Even as he broke from their work in a decisive manner, many of the themes of Marx’s critique of political economy stem directly from the issues the classicals attempted to tackle. That’s why the overview provided in previous sections of this chapter is so crucial to understanding Marxian economics.

Still, the question remains, how does Marx’s critique of the mainstream economics of his day transfer over to contemporary mainstream economists? As we will see, although neoclassical and Keynesian economists reject the labor theory of value and other crucial elements of classical political economy, both the basic assumptions and conclusions of their approach are so similar to those of the classicals as to make it a relatively short step from Marx’s critique of the mainstream economic theory of his day to that of our own.

However, before we look at that theoretical encounter, in the next chapter, we will see how Marx’s critical engagement with classical political economy emerged over the course of his writings before, in the mid-1860s, he sits down to write the three volumes of his most famous book, Capital.

———

*Mill did defend various redistributive tax measures, in order to limit intergenerational inequalities that would otherwise constrain equality of opportunity. Moreover, he argued in a later edition of his Principles of Political Economy in favor of economic democracy: “the association of the labourers themselves on terms of equality, collectively owning the capital with which they carry on their operations, and working under managers elected and removable by themselves” (Principles of Political Economy, with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy, IV.7.21).